Members of the Kuosi society express the authority, affluence, and strength of the ruler through masquerade.

Elephant (Aka) Mask, 20th century (Kuosi Society, Bamileke Peoples, Grassfields region of Cameroon), cloth, beads, raffia, fiber, 146.7 x 52.1 x 29.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum) Speakers: Dr. Peri Klemm and Dr. Steven Zucker

Elephant mask, 1900–50 (Bamileke peoples), raffia cloth, indigo dye, glass beads, and cotton cloth, 111.2 x 48.3 x 17.7 cm (The Museum of the Fine Arts, Houston)

On May 6, 2023, Charles III and his wife, Camilla, were crowned at Westminster Abbey as the king and queen of the United Kingdom and its other Commonwealth realms. The newly crowned monarchs, their family, and members of their court presented themselves to the public with distinctive attire and regalia. For instance, the men and women of the Order of the Thistle, an order of chivalry directly associated with the queen and with Scotland, donned accessories that are exclusive to them: a dark green velvet robe, a black velvet hat with white feathers, and gold insignia. Wearing these objects convey to the public their high status and their favor with the royals. [1]

Elephant mask ensemble of a Kuosi Society Member, 19th–20th century (Bamileke peoples), fabric, monkey fur, glass beads, feathers, reeds, string, horse tail, ivory, 192.41 cm high (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond)

In the case of the Bamileke peoples, the members of the Kuosi society (elephant society) are the only ones authorized to dance elephant masquerades, which convey the authority, affluence, and strength of the fon (king, ruler, or chief). [2]

Mask performers don a hooded facial covering perforated with beaded or trimmed eyeholes (for the individual to see). It might have other facial features, such as a stylized nose or a small hole for a mouth. The hooded facial covering includes two long panels (one in the front that evokes an elephant’s trunk and one in the back), and large discs (which are generally circular, but can be slightly oblong or trapezoidal) that allude to an elephant’s ears. In addition, mask performers usually wear prestige items: a tunic or skirts made from ndop (patterned cotton cloth dyed with indigo), a conical headdress constructed with red feathers, and a leopard skin pelt on the back. They may also carry a beaded horse tail flywhisk, which is also a prestige item.

Members of the Kuosi society are themselves powerful people: royalty, court officials, titled individuals, and high-ranking warriors. They appear and perform at public celebrations and funerals of those associated with the society and the fon. While the fon is directly associated with the Kuosi society and might dance, he might or might not wear the hooded facial covering. [3]

Left: full mask; right: face of mask (detail). Mask (mbap mteng), early 1900s (Bamileke peoples), cotton, burlap, glass beads, twine, leather, and wood, 139.7 x 50.8 x 19.1 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

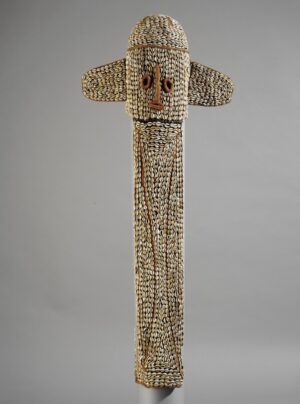

Elephant mask, acquired 1954, Bamileke peoples, cloth, fibre and cowrie shells, 135 x 55 x 25 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Display of wealth: materials in Bamileke elephant masks

The late art historian and curator, Dominique Malaquais, observed that Bamileke arts exhibit an abundant use of materials and horror vacui. This is evident in the elephant masks, which are embroidered and almost completely covered with beads (and in some cases, cowrie shells, or mbum) to make geometric and zoomorphic shapes and patterns. Some scholars believe that the colors of the beads carry significant meanings. For example, one art historian interprets the color black to be indicative of night and the dead. On the other hand, white is the same color as bones and is associated with ancestors. Some art historians have different interpretations about what the color red is associated with: the fon, life, blood, women, renewal, and rarity. [4]

Beads and cowrie shells are considered luxury items that were traded for (the beads came from Europe and the cowrie shells came from the Indian Ocean). In the 1800s, cowrie shells were used as a form of currency. As Malaquais puts it, “to sheath an item in mbum [cowrie shells] was quite literally to cover it in money.” [5] One of the elephant masks from The British Museum’s collection is covered entirely in cowrie shells, suggesting that it is immensely expensive.

Elephant mask, 1980s (Bamileke peoples) (The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis; photo: Wendy Kaveney, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Display of power: the “royal referents” of elephants and leopards

As scholar and curator Barbara Jarocki notes, “Beads are a display of wealth, but the royal referents are a display of power.” [6] The royal referents in these masks are elephants and leopards, which are considered to exhibit incredible strength and reasoning. Furthermore, they live in the wild, which is perceived as dangerous. Among the Bamileke peoples, the fon is believed to possess the qualities associated with elephants and leopards and to have the ability to mediate between human-occupied spaces and the wilderness.

Hervé Youmbi, Celestial Masks, part of Skulptir Projekte Münster, 2017, wood, glass beads, wood glue, cotton thread, silicone (photo: Pieter Delicaat, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Bamileke elephant masks in contemporary art

Many museums in the United States and Western Europe hold Bamileke elephant masks. Hervé Youmbi, a contemporary artist based in Douala, the largest city and economic capital of Cameroon, created (through consultation and collaborations with masking societies and makers) a series of masks for his project, Visages de Masques (“Faces of Masks”). This ongoing series addresses the production, function, and consumption of contemporary masks locally and internationally. One of the masks in this series combines a Bamileke elephant with a “screaming” mask (alluding to Edvard Munch’s 1893 painting, The Scream, and the 1996 slasher film, Scream). The decision to cross a Bamileke mask (as well as other masks) with a “screaming” mask was based on Youmbi’s experience witnessing members of the Ku’ngang society wearing these silicone, Chinese-manufactured masks in 2010 for a performance. The incorporation of these “screaming” masks shows that masquerades allow for innovation, creativity, and change. Youmbi’s masks in Visages de Masques challenge the ways in which we tend to discuss African masquerades (and by extension, African art) in dichotomies: “traditional” vs. “modern or contemporary;” “rural” vs. “urban;” “authentic” (used in ritual or worship contexts) vs. “inauthentic” (made and marketed towards tourists or galleries); and “static” vs. “dynamic.” [7]

Frank Christol, Members of the elephant society pose for a French missionary photographer in the market place of Bandjoun, c. 1928, photograph (National Museum of African Art, Washington, D.C. and Musée de l’Homme, Paris)

Historically, masks from Africa that have entered museum and gallery collections in the United States and Europe are not returned and are divorced from their original contexts. In the case of masks from Visages de Masques, Youmbi envisions that they will be exhibited internationally, but will travel back to Western Cameroon to be utilized for performances, going against the conventional way that masks have circulated across the world.

Notes:

[2] Fon is also spelled as fo in scholarship.

[3] Based on the extant scholarship, it is not definitive that the fon wears the hooded facial covering. This confusion seems to stem from a widely reprinted photograph by Frank Christol (above) of Bamileke elephant masquerades located in Bandjoun, Cameroon, dated c. 1928 or 1930. In this photograph, the central figure in the foreground, who dons the hooded facial covering and holds a flywhisk, is often identified as the fon. According to art historian Christraud M. Geary, this individual is Kamga II of Bandjoun. Likewise, according to art historian Suzanne Preston Blier, this individual is Fon Nkanga. However, Dominique Malaquais points out that this central figure is often misidentified as the chief. Moreover, chief Joseph Kamga is actually behind and mostly hidden by the central figure. She points out, “a fo…never dances with his face covered.” See Figure 11-34 in Christraud M. Geary, “Elephants, Ivory, and Chiefs: The Elephant and the Arts of the Cameroon Grassfields,” Elephant: The animal and Its Ivory in African Culture, edited by Doran H. Ross (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), p. 253.; Figure 55 from Suzanne Preston Blier, Royal Arts of Africa: The Majesty of Form (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1998), p. 193.; Figure 20 from Dominque Malaquais, “A robe fit for a chief,” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, volume 58, number 1–2 (1999), p. 30.

[4] The interpretations about the colors black and white come from Suzanne Preston Blier. Both Blier and Dominique Malaquais interpret red as the color associated with the fon and with life. However, Blier sees red in connection with blood and women, while Malaquais views it in relation to renewal and rarity. See Blier (1998), 193.; Malaquais (1999), p. 31.

[5] Malaquais (1999), p. 29.

[6] Barbara Jarocki, “Bamileke Beadwork: Royal Referents,” African Arts, volume 18, number 4 (1985), p. 86.

[7] For more on Hervé Youmbi’s Visages de Masques, see Hervé Youmbi’s Visages de Masques (Artist Statement and Project Description); Silvia Forni, “Masks on the Move: Defying Genres, Styles, and Traditions in the Cameroonian Grassfields,” African Arts, volume 49, number 2 (2016), pp. 38–53; Silvia Forni and Dominique Malaquais, “Village matters, city works: Ideas, technologies, and dialogues in the work of Hervé Youmbi,” Critical Interventions, volume 12, number 3 (2018), pp. 294–305; and Dominique Malaquais, “Playing (in) the Market. Hervé Youmbi and the Art World Maze,” Cahiers d’études africaines, volume 223 (2016), pp. 559–80.

Additional resources

This mask at the Brooklyn Museum

Another elephant mask at the Dallas Museum of Art

Hervé Youmbi’s Visages de Masques (Artist Statement and Project Description)

Suzanne Preston Blier, Royal Arts of Africa: The Majesty of Form (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1998).

Silvia Forni, “Masks on the Move: Defying Genres, Styles, and Traditions in the Cameroonian Grassfields,” African Arts, volume 49, number 2 (2016), pp. 38–53.

Silvia Forni and Dominique Malaquais, “Village matters, city works: Ideas, technologies, and dialogues in the work of Hervé Youmbi,” Critical Interventions, volume 12, number 3 (2018), pp. 294–305.

Christraud M. Geary, “Elephants, Ivory, and Chiefs: The Elephant and the Arts of the Cameroon Grassfields,” Elephant: The animal and Its Ivory in African Culture, edited by Doran H. Ross (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), pp. 228–57.

Pierre Harter, “The Beads of Cameroon,” Beads: Journal of the Society of Bead Researchers, volume 4, number 1 (1992), pp. 5–20.

Barbara Jarocki, “Bamileke Beadwork: Royal Referents,” African Arts, volume 18, number 4 (1985), p. 86.

Dominique Malaquais, “A robe fit for a chief,” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, volume 58, number 1–2 (1999), pp. 16–37.

Dominique Malaquais, “Playing (in) the Market. Hervé Youmbi and the Art World Maze,” Cahiers d’études africaines, volume 223 (2016), pp. 559–80.

Kate Ezra Martin, “Splendor and secrecy: Art of the Cameroon Grasslands,” African Arts, volume12, number 4 (1979), pp. 79–81.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Kuosi,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Brooklyn Museum, looking at this magnificent beaded mask.

Dr. Peri Klemm: [0:10] This mask is covered in beads. It was danced by the members of the Elephant Society, the Kuosi Society, in the Bamileke kingdom of Cameroon.

Dr. Zucker: [0:21] Cameroon is a country in Central Africa, but we’re seeing this object hermetically sealed within Plexiglass in a museum, completely divorced from the way that it would have been used and understood in its original context.

Dr. Klemm: [0:34] This was a masquerade, which involved not just a mask but a costume, performers, musicians, and attendants to bring this mask to life, to do what it was really supposed to do in terms of honoring the king and bringing about social harmony.

Dr. Zucker: [0:49] So we should not be seeing it frozen, hung as if it was just a piece of cloth.

Dr. Klemm: [0:54] This object was obviously collected and has now a second life in this museum space. It’s very hard for us to re-contextualize its original use, but we know from photographs that the Bamileke society would wear these with a red feather headdress, a leopard-skin pelt, and a full-body costume.

[1:13] The leopard and the elephant were symbols of rule, and powerful symbols for the Fon. The Fon was a divine king who could transform into the elephant, and the leopard was thought to be an animal that could transform into a human. We have that connection between divine rule and the essence of these powerful animals.

Dr. Zucker: [1:35] The Bamileke that would have worn this would have been court officials, title holders, warriors, people that held, themselves, great power, and in their association with the leopard and with the elephant, would have expressed the power of the king and, in a sense, the political stability of that hierarchical order.

Dr. Klemm: [1:52] The Bamileke king, the Fon, allowed this society, and only this one, to dance the elephant mask and to wear leopard skin. They were entrusted with these symbols of authority and power. The main form in this beaded piece is the isosceles triangle, which relates to the patterning on the body of the leopard.

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] Highly stylized, though, as the entire mask is. It’s dazzling, and it has a optical quality that is full of energy and dynamism.

Dr. Klemm: [2:27] Imagine when it’s worn and danced and performed, it would be incredibly dynamic with all of these various materials and colors and shapes, all brought together to suggest the power of that king.

Dr. Zucker: [2:40] In Cameroon today, the Bamileke still perform this ritual — now annually — but instead of warriors performing it, these are powerful members of the society.

[2:49] [music]