Obelisks

How did all of these monuments from Egypt end up in Rome? When were they transported and why?

Chapter

The Roman empire in a connected world, 27 B.C.E.–330 C.E.

Tondo of Two Brothers, c. 140 C.E., encaustic paint on wood, 61 cm diameter (Egyptian Museum, Cairo). Excavated in 1898–99 at Antinoöpolis, Egypt

A vivid red cloak fastened by a gemstone pin. A creamy white cloak over a tunic with a purple stripe. A v-shaped face and an oval one. Curly hair, wispy and thick. Brown eyes, golden and dark. Facial hair above lips and along a jawline. When we look closely at these painted portraits from Egypt, we see the faces and clothes of individuals living in the Roman empire around 140 C.E. Scholars debate whether they are relatives, friends, or lovers.

The painting captures the cultural complexity of their world. Sketched above their shoulders are bronze statues of gods, with mixed Greek and Egyptian attributes. An Egyptian date (15 Pachon), written in Greek letters, can be seen on the left. One sleeve has an embroidered swastika, an ancient Eurasian symbol of unending prosperity.

At the time the portraits were painted, the Roman empire’s territory stretched across northern Africa, western Asia, and Europe. All of these places had art and architectural traditions older than the empire itself. Some, like Egypt’s, were far older. Egypt had become a Roman province around 30 B.C.E., when the great pyramid at Giza was already 2,500 years old and considered a wonder of the ancient world. Pyramids were far from being relics of the past, however, because they were still being built. In the city of Rome, Italy, a magistrate named Gaius Cestius constructed one around 12 B.C.E. Steep proportions make his Roman tomb look like the Pyramids of Meroë (in modern Sudan) just beyond the Roman empire’s southern border.

Left: Giza pyramids, Egypt, 2600–2500 B.C.E. (photo: Ikiwaner, CC BY-SA 2.0); center: Pyramids of Meroë, Kingdom of Kush, Sudan, c. 300 B.C.E–350 C.E. (photo: Fabrizio Demartis, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Pyramid of Gaius Cestius, Rome, c. 12 B.C.E., 37 x 30 m (photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Despite such powerful cultural legacies, art histories of the Roman empire often focus on the might of one city: Rome.

This chapter tells a different story, one concerned with the empire’s geographic breadth and cultural plurality. Focusing on portraits and public architecture reveals how one of the world’s largest empires was experienced by real people like the ones in the painting above. Reintroducing the city of Rome and its emperors at key moments allows them to join an ensemble of characters and settings in an art and architectural history that stretches empire-wide.

Sites mentioned in this essay (underlying map © Google)

Ancient Rome and globalization

Historical records date Rome’s founding to 753 B.C.E., and leaders expanded the city’s territory for the next thousand years.

Scholars have divided this long history into three eras defined by different governments:

753–509 B.C.E.

This is the Monarchy or Regal period, with a king and a senate.

509–27 B.C.E

This is the period of the Republic, with elected magistrates and a senate.

27 B.C.E.–330 C.E.

This is the period of Empire with an emperor, elected magistrates, and the enduring senate.

This chapter addresses the third phase, when Rome’s territory reached its greatest extent. Road systems and sailing routes created an early phase of globalization in this era, with people, commodities, and ideas moving through highly connected territories on three continents.

Obelisk in Piazza del Popolo (Flaminian Obelisk), Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Peace, plunder, and the first emperor

After a period of civil war, an aristocrat called Augustus became Rome’s first emperor in 27 B.C.E. As emperor, Augustus had extensive military power and ruled alongside elected officials and the Roman senate. Monuments from his reign reveal the complicated backstory of ongoing imperial expansion.

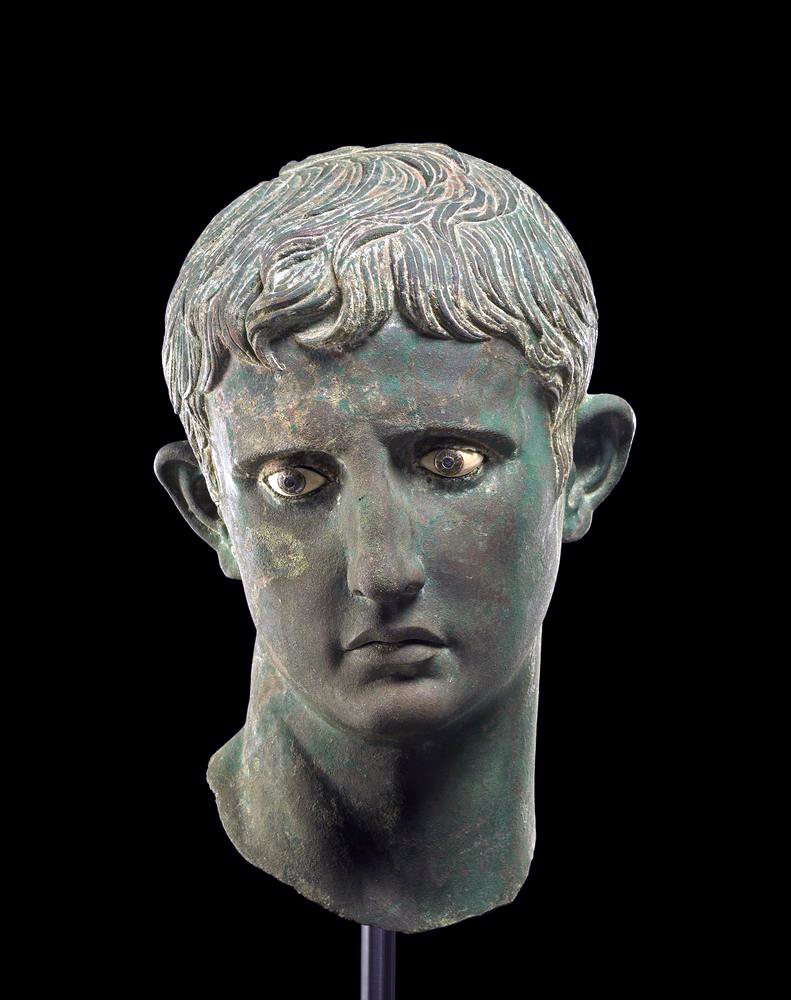

Augustus was the leader responsible for annexing Egypt. He commemorated this feat by seizing two obelisks from Heliopolis (Cairo), transporting them to Rome, and rededicating them as victory monuments.

The kingdom of Kush in Sudan, Africa, contested Rome’s claim to Egypt. Its representatives captured and mutilated a portrait of Augustus: the severed bronze head was placed beneath the steps of a Kushite temple. At the same time, the Parthian army from Iran seized Roman military standards while fighting the empire’s expansion in the eastern Mediterranean. Augustus’ reclaiming of these standards was presented as a great victory on the armor of what has become his most famous portrait (the Augustus of Primaporta).

These acts of looting—Augustus’ claiming of Egyptian obelisks, the Kushite claiming of a portrait of Augustus, and the Parthian claiming of Roman military standards—demonstrate how much cultural violence occurred as the empire’s borders expanded.

Watch videos and read essays about Augustus and imperial expansion

Meroë head of Augustus

This head once formed part of a statue of the Roman emperor Augustus who appears larger than life, with perfect proportions based upon Classical Greek notions of the ideal human form.

/3 Completed

Relief sculpture of Epona framed by four horses, 4th century C.E., marble, 68.7 x 141 x 16 cm (Archaeological Museum, Thessaloniki; photo: QuartierLatin1968, CC BY-SA 3.0). Excavated in 1962 at Thessaloniki, Greece

Many gods, many temples

Most of the empire’s communities believed that there were many gods, and their polytheistic religions were open and fluid. Gods favored in one region could be worshiped anywhere. A good example is Epona, a Celtic goddess associated with horses. Honored extensively in France (Gaul), she became popular with Roman cavalry troops who spread her worship to many different regions of the empire. New gods could also be invented to address emerging concerns, and emperors and their heirs were sometimes honored as gods after their deaths.

A shared belief in reciprocity—that help from the gods should be rewarded with gifts—generated much of the empire’s art and architecture. Many religious sites pre-dating the empire’s expansion remained in use with new offerings. Amun’s sanctuary in Karnak, Athena’s Parthenon in Athens, and Sulis’ sacred spring at Bath all continued to attract worshippers.

The Maison Carrée was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023. Maison Carrée, Nîmes, Provence, c. 4–7 C.E., 26.42 x 2.85 x 13.54 m (photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In newly constructed temples, design and decoration varied widely. Nîmes (Nemausus, France) had a temple that resembled many in Rome, with a podium, central stairway, and encircling columns. This temple was dedicated to Augustus’ deceased grandsons, but altars and art throughout the city honored a wide range of deities, including Celtic ones and those favored by immigrants from distant lands.

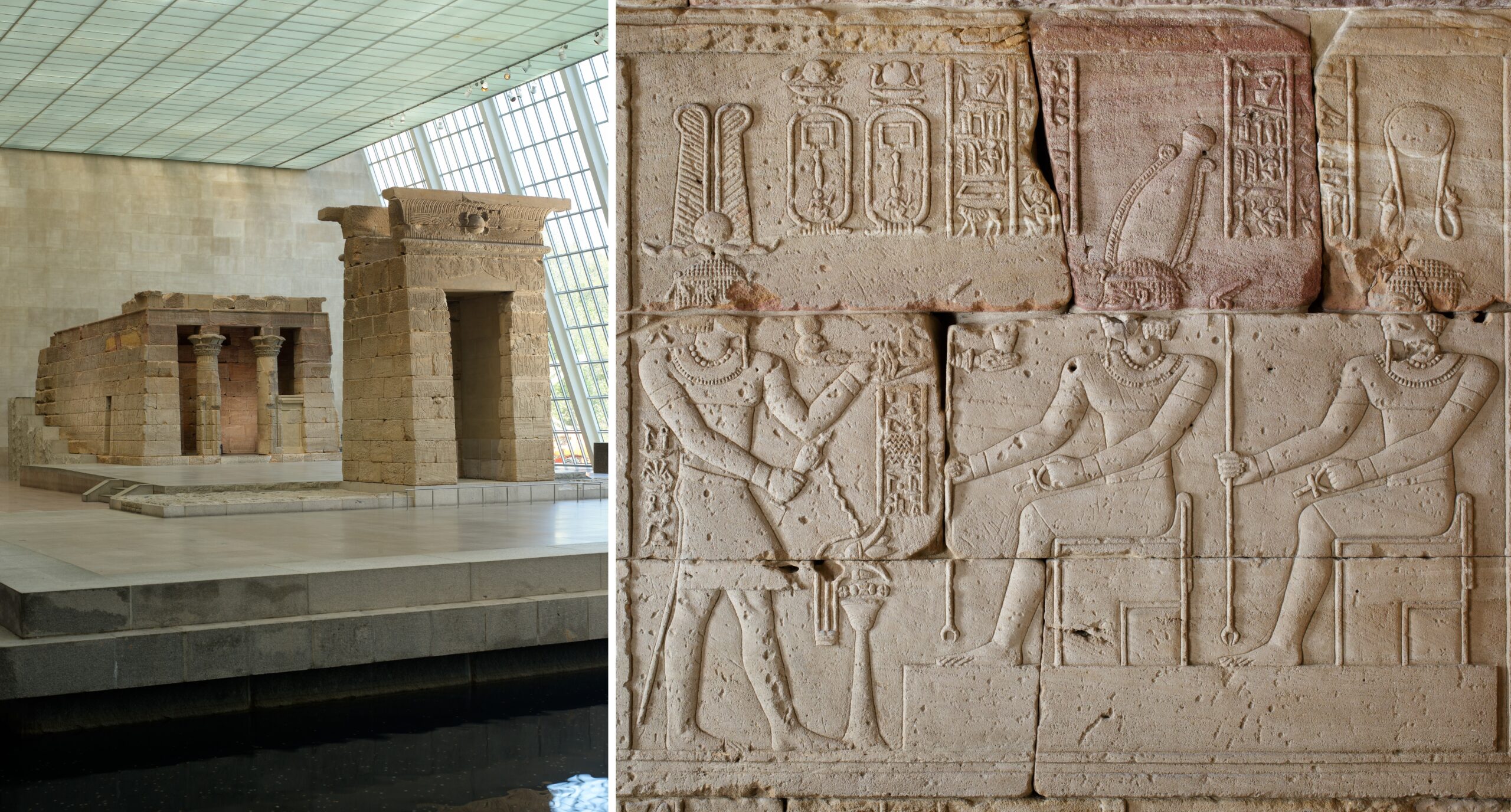

Left: The Temple of Dendur, from Egypt, Aeolian sandstone, 6.4 x 6.4 x 12.5 m; right: vignette on the interior south wall of the porch showing Augustus (left) burning incense and pouring a libation in front of the figures of Pedesi and Pihor (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In Egypt, traditional building plans, column styles, and imagery persisted in many areas. One of the best examples is a small temple from Dendur, which honored the Egyptian goddess Isis and the deified sons of a local Nubian ruler. In the temple’s relief sculptures, Augustus appears as an Egyptian king wearing a ceremonial kilt and headdress and presenting offerings to Isis and other deities. This is one of many temples in Egypt where Roman emperors are shown fulfilling the king’s duty to the region’s gods.

Learn about the many gods and temples of the ancient Roman world

Maison Carrée

The Maison Carrée, c. 4–7 C.E., in France, is an extremely well preserved ancient Roman temple.

The Temple of Dendur

Emperor Augustus is depicted among the Egyptian gods on this temple from Nubia.

Read Now >

Aquae Sulis, Bath, England

Celtic and Roman deities were worshiped in the temple at Aquae Sulis.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Mérida was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993. Roman theater, Mérida (Emerita Augusta), Spain, built in 16/15 B.C.E. and remodeled in later centuries, 86.63 m diameter (photo: Benjamín Núñez González, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sports and entertainment

The empire’s residents could go to an amphitheater to attend gladiatorial fights and animal hunts; a circus for chariot races; a stadium for track and field events; a theater for comedies, tragedies, and mimes; and an odeum for concerts and poetry readings. Of these buildings, only the amphitheater developed in Italy; the rest arose in Greece, but were popular in many of the empire’s cities.

Rome’s historic center was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1980. Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater), Rome, c. 70–80 C.E., 189 x 156 m (photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

When Rome’s Colosseum was dedicated around 80 C.E., it became the empire’s largest gladiatorial venue. At least 273 amphitheaters eventually stood around the Mediterranean world, one of the most visible ways that cities changed during the era of Roman rule. Locally elected magistrates typically paid for these buildings and their events. The gladiators who fought in them had low social status and short lives, and they were celebrated as sports heroes in art.

Cup depicting gladiatorial games, c. 50 C.E., mold-blown glass, 7.1 x 7.5 cm (Corning Museum of Glass, New York). Found in Chavagnes, France, in the late 19th century.

The amphitheater at El Djem (Thysdrus), Tunisia, one of the empire’s largest, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979. Constructed in the 3rd century C.E., 148 x 122 m (photo: Kirk k, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Locations of Roman amphitheaters (map: Sebastian Heath)

Watch a video about the empire’s largest gladiatorial venue

/1 Completed

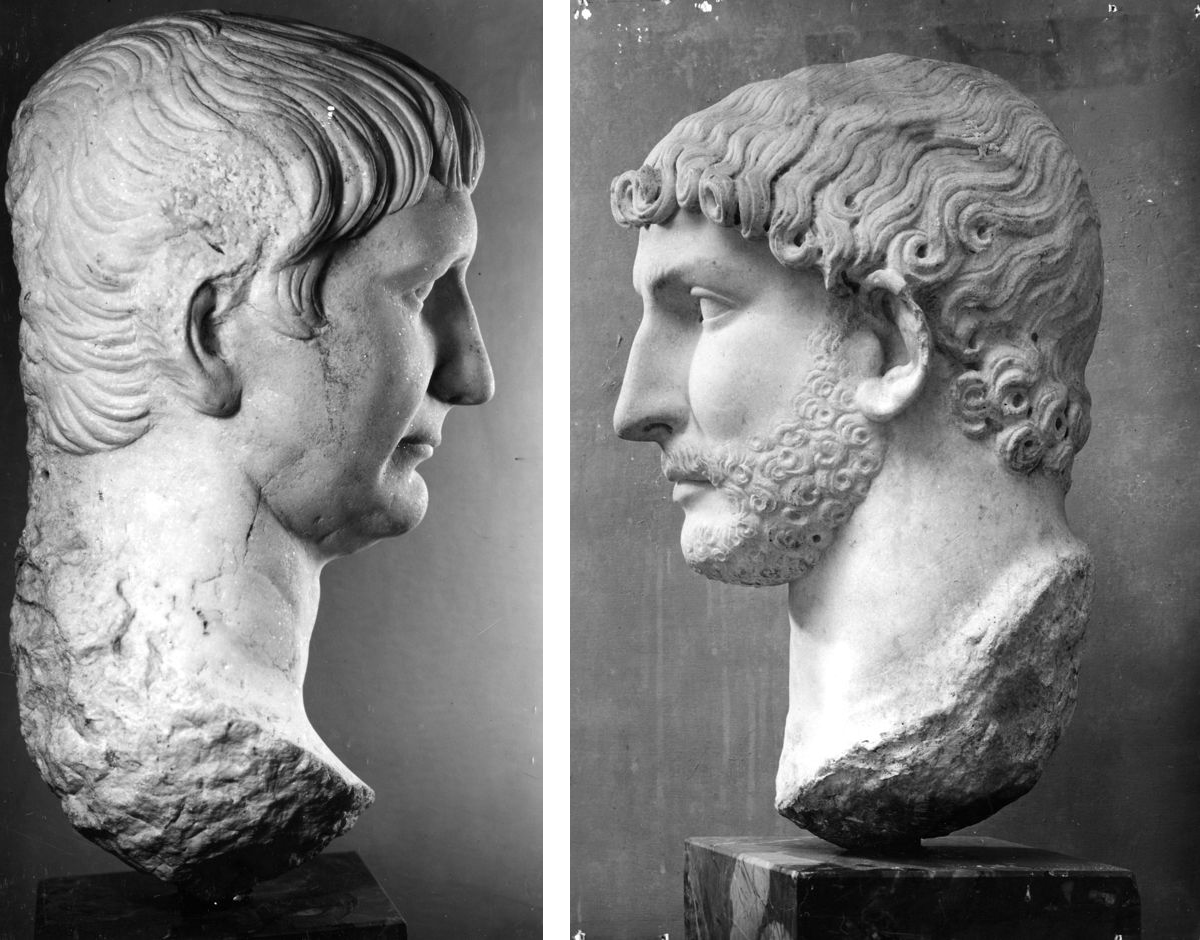

Left: Portrait of Trajan, c. 117 C.E., marble, 48 cm; right: Portrait of Hadrian, c. 117 C.E., marble, 54 cm (photos: Virtual Museum of Ostia, Museo Ostiense, Ostia, nos. 14 and 32). Both portraits were excavated in Ostia, Rome’s port city

Emperors from Spain in Rome

People from the empire’s provinces gradually took the lead in culture, politics, and the military. The emperors Trajan and Hadrian hailed from Italica (an ancient Roman city in Spain), and came from mixed families of Italian colonists and Spanish elites.

The ground-breaking architect for these emperors was Apollodorus, a Greek-speaking Syrian from Roman Damascus.

Column of Trajan (relief narrative wraps upward 23 times, and would be roughly 200 m long if unwound), Forum of Trajan, Rome, 106–113 C.E., marble, 38.4 m high (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In Rome, relief sculptures on a monumental column depict the emperor Trajan leading military campaigns in Romania (Dacia). One scene represents a bridge that Apollodorus designed for the Roman army to cross the Danube river. The bridge, made of masonry pillars and wooden archways, dominates the top of the scene. A religious ceremony led by Trajan takes place on the shore.

Trajan preparing to sacrifice a bull in front of the bridge that Apollodorus built across the Danube. Soldiers hold tall military standards to the left, and Trajan displays an offering dish above a small altar (detail), Column of Trajan, Forum of Trajan, Rome, 106–113 C.E., marble, 38.4 m high (photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, from a cast in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Scene 64/LXIV: cavalrymen from Roman Morocco (Mauretania) confront Dacian warriors on foot (detail), Column of Trajan, Forum of Trajan, Rome, 106–113 C.E., marble, 38.4 m high (photo from casts 157–158, now in the Museo della Civiltà Romana, Rome; photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Another scene shows a military strike by a cavalry troop recruited from Roman Morocco (Mauretania). This troop (on the left) stands out because of its careful hairstyling with long ringlets. Dacian soldiers make a different impression. They appear (on the right) with unstyled hair and long messy beards, signs of barbarism in the eyes of the Roman elite.

While the relief sculptures celebrate the imperial work of many individuals from the provinces, they stereotype Dacians as barbarians to justify the invasion.

Markets of Trajan, Rome, c. 100–112 C.E. (photo: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Senate and Roman People (Senatus Populusque Romanus, SPQR) dedicated this sculpted column to Trajan to honor him for financing a new forum (town square) in Rome. Apollodorus was responsible for designing the forum, which required a hill to be scaled back. He also designed the neighboring market complex, where he used concrete to create curved spaces with vaulted ceilings. These advances in engineering culminated in the Pantheon, the magnificent domed temple now thought to have been initiated by Trajan, completed by Hadrian, and designed by Apollodorus. In these and many other ways, people from the provinces shaped the empire’s frontiers as well as Rome’s cityscape.

Watch videos about emperors from Spain in Rome

Markets of Trajan

The architect was Apollodorus, a Greek-speaking Syrian from Roman Damascus

The Pantheon

While the Pantheon’s importance is undeniable, there is a lot that is unknown.

/2 Completed

View of the arch monument dedicated to emperor Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna in 217 C.E. at Volubilis, Morocco. Volubilis was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997 (photo: damian entwistle, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Cities, forts, and communities

Many of the empire’s cities and forts survive as archaeological sites, and each offers a different perspective on daily life. [1] Pompeii, for instance, reveals how one of Italy’s oldest cities changed under Roman rule. The forts along Hadrian’s Wall in Britain preserve sculpted tombstones honoring people from as far away as Morocco. And at Dura-Europos, Syria, art and architecture document the coexistence of polytheism, Judaism, and Christianity on a border contested by the Parthian and Sasanian empires of Iran.

Watch videos and read about cities, forts, and communities

Pompeii

Pompeii, once called the “City of the Dead,” gives a marvelous sense of day-to-day Roman life.

Hadrian’s wall

Hadrian’s Wall in England has always been a place where communities intersect.

Dura-Europos

The ancient site now known as Dura-Europos (in what is today Syria) was a diverse town which negotiated its place on the frontier between East and West.

/3 Completed

Portraits and identities

Many of the empire’s residents encountered portraits in their daily lives. These images appeared in public squares, temple precincts, cemeteries, and homes. They were made in a range of media including statues, relief sculptures, paintings, cameos, and gems. Portraits also defined the empire’s coin-based monetary system, legitimized by images of the emperor and his family.

Some portraits prioritized recognizable resemblance (a realistic likeness), with flaws emphasized (verism) or minimized (idealism). Alternatively, some used generic bodies to emphasize social roles more than individuality. These approaches co-existed, and many portraits combined symbols, poses, and inscriptions to communicate complex identities.

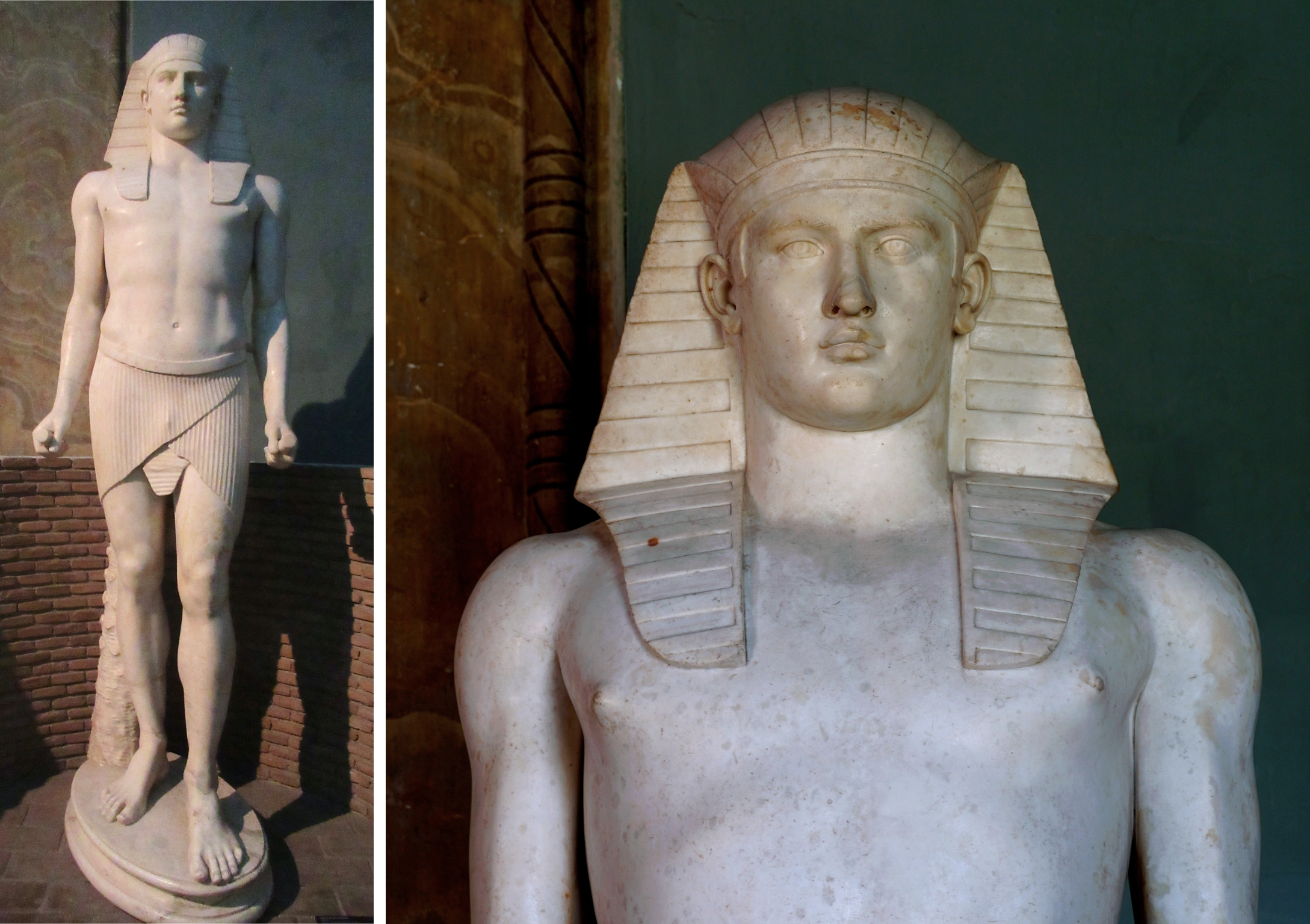

Statue of Osiris-Antinous, from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, c. 135 C.E., Parian marble, 241 x 77 x 79 cm (Vatican Museums; left photo: Damien Tournay, CC BY-SA 2.0; right photo: Slices of Light, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This statue, from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, presents an idealized likeness of the emperor Hadrian’s lover Antinous, who is shown in the imagined clothing of Osiris (the Egyptian god of the dead), an allusion to his untimely death in the Nile river and subsequent recognition as a god.

Relief sculpture showing Scribonia Attica sitting before a pregnant woman in a birthing chair, terracotta plaque, 28 x 41.5 cm (Museo Ostiense, Rome; photo: Parco Archeologico di Ostia Antica). Found in 1930 in the Isola Sacra necropolis, tomb 100

Although elites like Antinous were rarely depicted doing physical labor, people who worked for a living often emphasized professional pride in their tomb portraits. Scribonia Attica, a midwife at Ostia, showed herself at work.

Tombstone depicting two freed (formerly enslaved) women named Turrania Philematio and Chia, who gaze at each other, c. 50 C.E., painted limestone, 117 x 53 x 39 cm (Musée Départemental Arles Antique; photos: Dr. Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Found reused in 1810 during the demolition of the Arc de l’Archevêché at Arles, France

Portraits also represented people with different levels of freedom: the empire’s population included free, enslaved, and formerly enslaved individuals. Enslaved persons often came from active war zones, especially in Europe, because generals could sell defiant populations for profit. Emancipation, the granting of freedom, was also widely practiced.

Much of our knowledge about freed people comes from the tombstones that they commissioned for themselves and their loved ones. They typically note their status in inscriptions, with libertus meaning a freedman and liberta meaning a freedwoman in Latin.

Explore portraits and identities in these videos and essays

Women in Roman art

Sculptural portraits and wall paintings were a common way that non-elite women, across the empire, articulated their identities and their work.

Fayum: Mummy of Herakleides

During ancient Egypt’s last dynasty, cultural exchange on a massive scale occurred between Greeks and Egyptians.

Palmyra: Funerary relief of Viria Phoebe and Gaius Vurus

A remarkable assemblage of funerary portraiture grants us a glimpse at the self-styled identity of a number of the city’s former occupants.

Lullingstone: Two portrait busts

Found during an excavation in 1949, Lullingstone Roman Villa, Kent.

/4 Completed

Recent tests have found pigments proving that the portraits were colorfully painted. Acquired in 1975, these portraits do not have a documented findspot. Portrait busts of Septimius Severus and Julia Domna, c. 200–210 C.E., marble (Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, Bloomington)

An emperor from Libya and an empress from Syria

In the late 2nd century C.E., another dynasty from the provinces claimed power. Septimius Severus came from an old family in Khoms (Lepcis Magna), Libya, where the Punic language was still spoken. His wife Julia Domna came from an old family in Homs (Emesa), Syria, where Syriac and Greek were still spoken. Although the empress’ role was ceremonial, Julia Domna traveled more than any of her predecessors, and her portraits survive in great numbers. The couple’s son Caracalla left a lasting mark on Rome’s cityscape by constructing a spectacular public bathing complex with soaring curved ceilings, colorful mosaic floors, and a statue collection.

Learn about the Severan dynasty

Portraits of Julia Domna

In Britannia (the Latin name for the Roman province of Britain), Julia Domna and her husband the Roman emperor Septimius Severus were a long way from home.

Baths of Caracalla

Bathing was an essential part of ancient Roman urban life and spending the afternoon in the baths was a normal occurrence.

/2 Completed

The Sasanian king Shapur I appears on horseback while grabbing the wrists of the Roman emperor Valerian to show his capture. Before him kneels the Roman emperor Philip I from Arabia, and beneath the horse lies the body of the Roman emperor Gordian III. Rock-cut reliefs from Naqsh-e Rostam (left) and Bishapur (right), Iran, c. 241–272 C.E. (left: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0; right: youngrobv, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Emperors defeated in Iran

After the fall of the Severan dynasty in 235 C.E., emperors struggled to assert control over the empire’s vast territory. The Roman military suffered defeats, especially in battles against the Sasanian empire of Iran. [2] Sasanian kings drew on their region’s long history of monumental art to commemorate their victories. Sasanian images of vanquished Roman emperors offer an important counter-narrative, because the Roman military is never shown losing in Roman art.

Part of an interior frieze depicting the elder tetrarch Diocletian and the younger tetrarch Maximian embracing in cooperation at the end of a procession, c. 300 C.E., painted marble, 1 m high (Kocaeli Museum, İzmit). Found in excavations of a ceremonial building at İzmit (Nicomedia, Türkeyi) in 2001/2009

From Rome to Istanbul

To counter the chaos of the 3rd century, the Roman emperor Diocletian led an experiment in shared rule. Two senior emperors and two junior emperors divided the empire into quadrants and developed capital cities away from Rome. Portraits of this Tetrarchy, meaning the “rule of four,” emphasize visual similarities among the emperors sharing power.

Coin depicting Constantine I, 327–328 C.E., bronze, 2 cm diameter (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London). The coin was minted in Alexandria, Egypt, and excavated in 1914 at Antinoöpolis, Egypt, the city that Hadrian established in honor of his deceased lover Antinous. The double painted portrait at the beginning of the essay was also excavated at Antinoöpolis

The emperor Constantine I began as a tetrarch, but eventually re-established sole rule. He also acknowledged Christianity as one of the empire’s official religions and developed Constantinople (Istanbul, Türkiye) as his primary capital. Scholars consider his reign a turning point from the Roman Empire to the Byzantine Empire. These modern terms are misleading, however, because leaders based in Constantinople continued to call themselves Roman and their realm the Roman empire.

This granite obelisk was transported by Theodosius I in 390 C.E. and placed on a new base. The obelisk was originally set up by Thutmose III (1479–1425 B.C.E.) at Karnak, Egypt (Constantinople, now Istanbul) (photo: Erik Cleves Kristensen, CC BY 2.0)

Like all of the empire’s cities, Constantinople drew inspiration from Mediterranean-wide precedents. Rome’s own multicultural cityscape offered one model. The Byzantine emperor Theodosius I transported an ancient obelisk from Egypt to Istanbul, just as Augustus and other emperors had done for Rome.

Learn about the Tetrarchy and the move from Rome to Istanbul

/1 Completed

The Roman archaeological site at Djémila (Cuicul, Algeria) was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982. The Severan Forum and Temple of the Gens Septimia, Djémila (Cuicul, Algeria), 229 C.E. (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The politics of cultural heritage

Archaeological sites from the Roman era can be found in more than thirty modern nations, where they have been shaped by changing cultural traditions, archaeological practices, and heritage laws. In all of these lands, policies of reconstruction or destruction have served political movements aiming to build or break connections to the past. To promote preservation, many places from the Roman empire are now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites. Yet Europe is over-represented on UNESCO’s list, and the empire’s territories are still unevenly addressed in teaching and learning resources. Emerging scholars can make an important contribution by developing expertise across the many fascinating regions that defined the Roman empire’s connected world.

Khoms (Lepcis Magna), birthplace of the emperor Septimius Severus, was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1982. Theater, Khoms (Lepcis Magna), Libya, built in 1/2 C.E. and remodeled in later centuries, 87.6 m diameter (photo: public domain)

Explore World Heritage sites from the Roman era

The Mausoleum of Augustus

Part of the historic center of Rome, the Mausoleum of Augustus represented the political ambitions of Augustus and his family.

Read Now >

Destruction of Palmyra

Declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO, the archaeological site of Palmyra has suffered irreversible damage from the Syrian civil war.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Notes:

[1] Other places well-preserved as archaeological sites include Herculaneum in Italy; Glanum and Vaison-la-Romaine in France; Baelo Claudio and Italica in Spain; Sarmizegetusa in Romania; Gamzigrad in Serbia; Ephesus and Aphrodisias in Turkey; Apamea and Palmyra in Syria; Dendera, Edfu, and Philae in Egypt; Lepcis Magna and Sabratha in Libya; Bulla Regia and Dougga in Tunisia; Djémila and Timgad in Algeria; and Volubilis in Morocco. Scattered remains from the era of Roman rule exist throughout these regions in cities and rural areas.

[2] Touraj Daryaee, “Persia and Rome: the Historical and Ideological Gaze,” Persia: Ancient Iran and the Classical World, edited by Jeffrey Spier, Timothy Potts, and Sara Cole (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2022), pp. 283–91.

Key questions to guide your reading

If culture is defined as the customary beliefs, social rituals, or material expressions of a particular group, which artworks or buildings would you choose to discuss cultures in the Roman empire?

What can portraits tell us about the empire's residents, including the emperor and his family?

How would you describe the sensory experience of the empire's architecture? Think about the use of light and shadow; straight and curved spaces; materials and decoration.

How does the Roman empire compare to other empires you have studied? Which artworks and buildings would you use to make those comparisons?

Jump down to Terms to KnowIf culture is defined as the customary beliefs, social rituals, or material expressions of a particular group, which artworks or buildings would you choose to discuss cultures in the Roman empire?

What can portraits tell us about the empire's residents, including the emperor and his family?

How would you describe the sensory experience of the empire's architecture? Think about the use of light and shadow; straight and curved spaces; materials and decoration.

How does the Roman empire compare to other empires you have studied? Which artworks and buildings would you use to make those comparisons?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Learn more

An Indian ivory statuette in Pompeii

Explore Sudan’s Pyramids of Meroë

For the reconstruction of the Temple of Dendur’s ancient coloring and modern political significance, see Erin Peters, “Coloring the Temple of Dendur,” Metropolitan Museum Journal, volume 53 (2018), pp. 8–23.

Erin Peters, “Dendur and Deleuze: The Becoming-Icon of American Egyptology at the Met,” Archaeologies, volume 19 (2023), pp. 83–103.