View of the main pool (“Great Bath”) of the Roman spa fed by the sacred spring, Bath, England, constructed from the 1st to 5th centuries C.E., the pool is now open to the sky and surrounded by later buildings (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

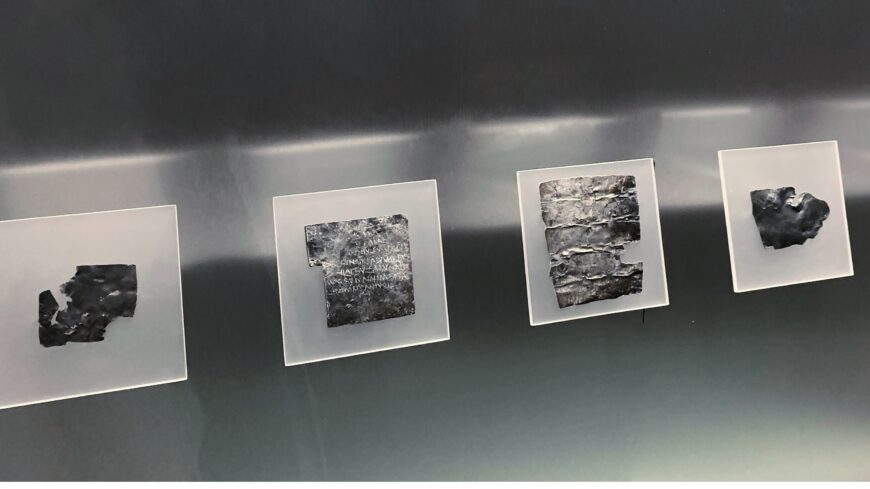

If you have ever tossed a coin into a fountain and made a wish, you are in good company. Residents of the Roman empire did this too, especially at naturally occurring fountains called springs. They also tossed in curse tablets (defixiones), and this one from Aquae Sulis (Bath, England) presents a common complaint.

From Docilianus, son of Brucerus, to the most holy goddess Sulis: I curse the one who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether man or woman, whether enslaved or free, that…the goddess Sulis inflict death upon them…and not allow them sleep or children now and in the future, until they have brought my hooded cloak to the temple of her divinity.[1]

A selection of metal curse tablets recovered from the sacred spring’s reservoir, 2nd to 4th centuries C.E. (Bath, England), on view at the Roman Baths Museum (photo: Wanda Marcussen, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Having a coat stolen is a problem that people have been facing for a long time, and this victim sought justice from the Celtic goddess Sulis.

The natural hot spring that she controlled at Bath received both offerings and curses, and it also provided a perpetual source of flowing water for a luxurious Roman spa. As a natural site that changed dramatically under Roman imperial rule, Aquae Sulis preserves important evidence for religion and everyday life in the Roman province Britannia.

Map of Roman Britain, with Aquae Sulis circled (map: Simeon Netchev, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Beliefs shared and sites transformed

The Roman Empire had claimed Britannia in 43 C.E., with some of the local Celtic kingdoms supporting the invasion and some fiercely fighting against it. In the following decades, there were soldiers, traders, and travelers from all over the empire who visited the island. Like the island’s Celtic residents, these newcomers were polytheistic, meaning that they worshiped many gods and were open to honoring new ones. The names of more than 200 different deities are documented in Britannia, and Sulis is one of them. In the Latin language spoken by the newcomers, Aquae Sulis literally meant “the waters of Sulis.”

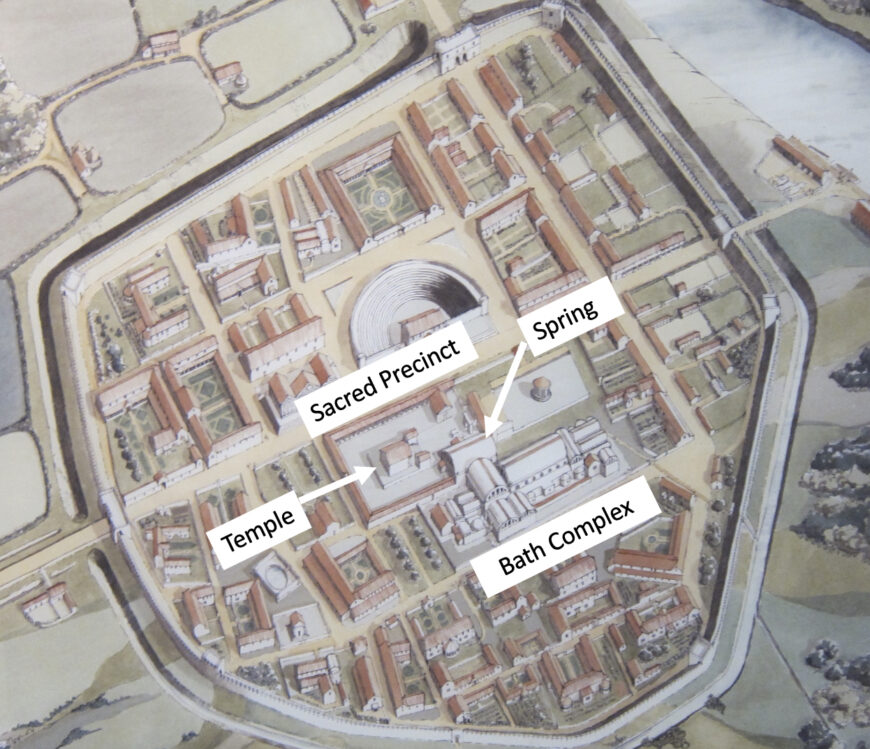

Thermal springs were popular throughout the Roman empire because their mineral waters were known to be good for the body and their miraculous natural warmth was thought to be the work of the gods. Under Roman rule, many of these natural sites were transformed with innovative spa facilities and fashionable stone temples. These changes are well-documented at Aquae Sulis, and a small town with commercial and residential areas gradually developed around the springs.

Reconstruction of Aquae Sulis at its fullest extent (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

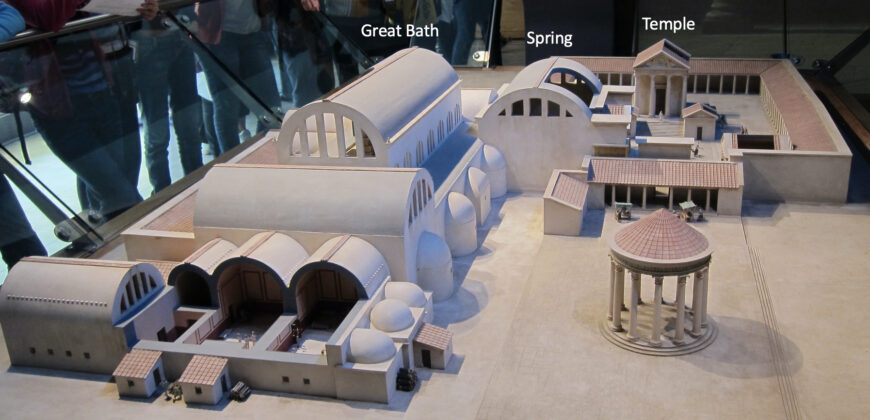

Architectural model showing Aquae Sulis as its fullest extent, with cut-away views revealing the insides of buildings (photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Redesigning a sacred site

Anonymous engineers began transforming the natural setting of Aquae Sulis around 75 C.E., about a generation after Rome’s arrival. These experts isolated the place where the main hot spring emerged, created a waterproof reservoir around it, and built a wall around the reservoir. [2] A stone temple and numerous altars arose to the northwest of the spring and a luxurious communal bathing facility took shape to the southeast of the spring. [3]

This site’s ancient design is difficult to see today because of later construction, but evidence for the sacred precinct and spa survives in stone foundations and pavements, lead pipes and panels, and even collapsed concrete ceilings. Ancient artifacts tell us how the spaces were used and by whom.

View of the sacred spring reservoir (the King’s Bath), Bath, England, now framed by modern buildings (photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Coins at the sacred spring

From the sacred spring and the reservoir surrounding it, archaeologists have recovered nearly 13,000 coins dating from the 1st to the 5th centuries C.E. Although most of the coins were official Roman currency, the earliest ones were minted by the Dobunni community and have the abstract patterning typical of the island’s coinage prior to the Roman conquest. If you look closely, you might see the shapes of horses amid some of the patterns. The presence of Celtic coins suggests that offerings were being made here even before the era of Roman rule.

Coins of the Dobunni people, bronze, 1st century C.E. (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: The Roman Baths, Bath and North East Somerset Council)

A shared belief in reciprocity—that help from the gods should be rewarded with gifts—motivated these and other offerings left in the spring. When you toss a coin into a fountain today, you likewise pay for the magical fulfillment of a wish. At Aquae Sulis, the goddess who granted such requests was also portrayed in a magnificent statue.

The surface shows signs of corrosion from the soil and damage from the statue’s destruction in late antiquity. Head of the goddess Sulis Minerva, gilt bronze, c. 75 C.E. (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Wanda Marcussen, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A golden goddess

One of the most remarkable finds from Aquae Sulis is a golden head, all that remains of one of the first monumental statues in Britannia. Made of lustrous bronze in the lost-wax casting technique and covered with layers of gold, the sculpture still gleams in an otherworldly way. Because of later damage to the site and imprecise excavations in the 1700s, we do not know exactly where the statue stood in the sacred precinct.

Bowl showing Minerva wearing a helmet, 1st century C.E., silver, 23.5 cm diameter, found at Hildesheim in 1868 (Antikensammlung, Berlin; photo: public domain)

The sculpture survives without a dedicatory inscription, but a key clue to its identity lies at the top of the head, where the break indicates that a helmet was once attached. Minerva was Rome’s helmet-wearing goddess, and images throughout the empire show her with a similar oval face, idealized features, and centrally parted, wavy hair.

At Aquae Sulis, Minerva’s name appears on many altars, offerings, and curse tablets, and they all help corroborate the head’s identity. In these inscriptions, her name is paired with that of Sulis. Some inscriptions mention them together as a single entity called Sulis Minerva, and some (like the curse tablet above) address Sulis alone. Visitors might have called this statue Sulis, Minerva, or Sulis Minerva. This process of matching gods from different religious systems occurred throughout the empire.

Showing gods in human form and naming them in inscriptions were both ways that religion changed in Britannia under Roman rule. Focusing worship around stone temples was another new practice.

From the temple, fragments of a column and pedimental sculptures now reconstructed in the Roman Baths Museum (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A new temple

Now in fragments, the site’s Roman temple (which measured 9 by 14 meters) initially had a tall podium (1 to 2 meters tall), a central staircase, and four Corinthian columns (8 meters tall) across its front. This formula for designing stone temples was popular in Rome and other cities of the empire, such as the Roman colony Nemausus (Nîmes, France). Such buildings typically housed a statue of a god or goddess, and religious activities took place in the surrounding courtyard.

Projected light restores the color and missing sections of the pediment (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Wanda Marcussen, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

At Aquae Sulis, the temple’s sculpted triangular pediment once soared high above the heads of the courtyard’s visitors. Today it can be seen up close in the site’s museum, where light is projected to complete the broken sections and restore the missing color.

The relief sculptures reveal a striking message. Two winged personifications of victory fly toward the center of the pediment. Their dresses flutter around them and their feet rest on globes. These winged victories were popular Roman symbols, so the fragmentary sculptures can be restored by comparison. The victories hold a large round shield adorned with two concentric oak wreaths, symbols of valor. At the shield’s center is a bearded face that has inspired debate, but likely represents Oceanus, the Roman god associated with the Atlantic Ocean. [4] Altogether, the imagery refers to Rome’s victorious expansion. These artworks are especially important because very few pedimental sculptures survive from Roman temples.

It is tempting to assume that newcomers constructed this temple, but allies on the island assisted Rome’s advance, and the building may have been funded by a member of the local elite who favored the new Roman imperial system. Future excavations may uncover new parts of the dedicatory inscription that could tell us.

Bathing together

Aquae Sulis flourished with Britannia’s most luxurious spa, fed by the sacred spring. We do not know who paid for the buildings or whether there was an entrance fee, but communal baths were typically accessible to all members of a community.

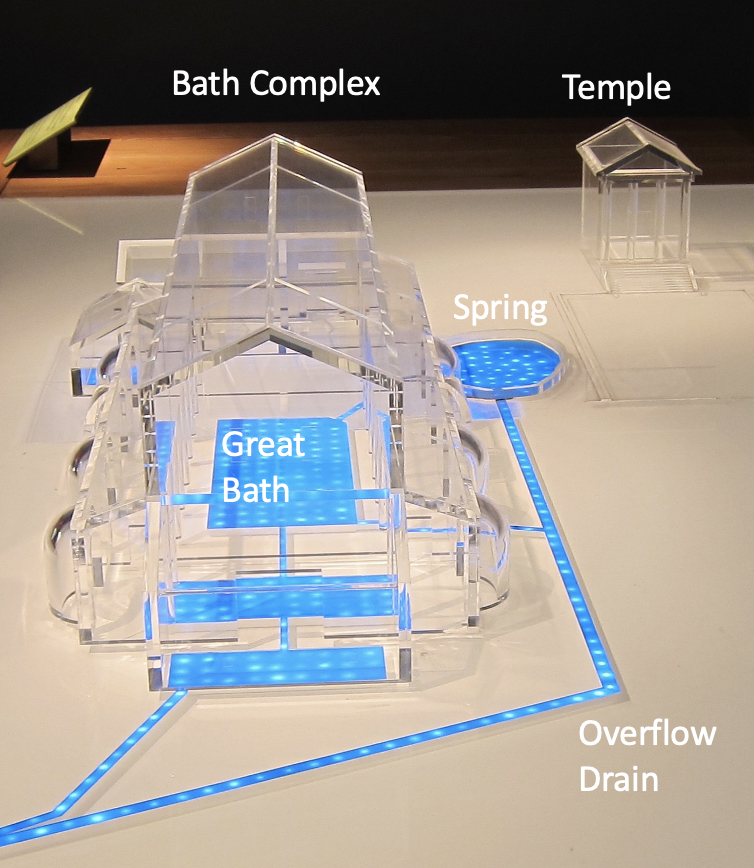

This model shows the flow of water from the sacred spring to the spa’s pools as well as the drainage system that took used and excess water away from the site (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The baths at Aquae Sulis were special because warm mineral water flowed continuously from the spring. Even now, the thermal waters reach about 115 degrees Fahrenheit, with a flowing rate of about 240,000 gallons a day. Most of the empire’s other spa facilities, such as the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, were supplied by aqueducts that channeled water from springs and rivers many miles away. [5]

View of the “Great Bath,” now open to the sky and framed by later buildings (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

At Aquae Sulis, the room with the largest pool (the “Great Bath”) is now misleadingly open to the sky. In the 2nd century C.E., its original wooden roof was replaced by a vaulted concrete ceiling, one of the largest on the island. This ceiling later collapsed, and surviving sections are now on display around the pool. Only the paving stones, column bases, and pool are ancient.

Northwest corner of the “Great Bath,” where water flows in from the sacred spring. The steps into the pool are visible through the water (photo: Simon Burchell, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The room (34 meters long, 21 meters wide, and approximately 20 meters high) was designed with the pool at the center, aisles for walking on either side and small curved apses likely used for seating. A conduit in the northwest corner brought warm mineral waters from the spring’s reservoir, and steps allowed bathers to access the pool (19 meters long, 9 meters wide, 1.5 meters deep) for restorative soaking. Like the spring’s reservoir, the pool was lined with lead panels for waterproofing.

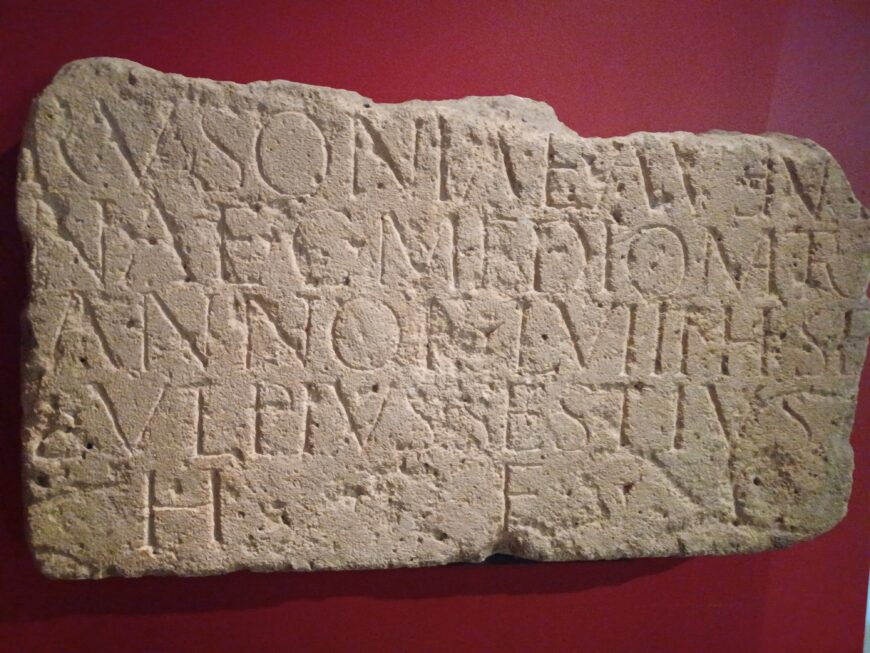

Funerary inscription honoring Rusonia Aventina, 2nd century C.E., stone, 50 x 94 x 10 cm, later reused in the city wall, found in 1803 (Roman Baths Museum, Bath; photo: Simon Burchell, CC BY-SA 4.0)

View of the “Great Bath,” now open to the sky and with the Gothic architecture of Bath Abbey visible in the background (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In many of the empire’s towns, going to the baths was an important part of daily social life, health, and hygiene. Facilities fed by thermal springs also attracted visitors from afar, and memorials from the surrounding town shed light on the people who lived and died at Aquae Sulis. One visitor, a woman named Rusonia Aventina, died here at the age of 58, having traveled from the territory of the Celtic Mediomatrici people in Roman France (ancient Gaul).

The fate of Aquae Sulis

The Temple of Sulis Minerva fell out of use by the late 300s C.E. when Christianity, a monotheistic religion, became more common. By the early 400s C.E., the Roman army had withdrawn from the island, and new groups began invading from northern Europe. Amid all of this change, the statue of Sulis Minerva was pulled down and hacked apart, and the Roman baths gradually became ruins. Yet the mineral waters kept flowing, and the town continued to develop around them. The settlement’s name eventually changed to Bath.

Modern legacy

In the 1700s, the Roman reservoir and spa were substantially rebuilt, and Bath flourished again as a bathing center. In 1987, UNESCO recognized Bath as a world heritage site, in part due to the Roman remains. Bathing is no longer permitted in the Roman pools, but visitors can still see the steaming spring water, walk around the ancient remains, and observe the elegant buildings from the 18th and 19th centuries that rise above them.