Hadrian’s Wall in England has always been a place where communities intersect.

Walltown Crags, Hadrian’s Wall (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Morag Myerscough, The Future Belongs To What Was As Much As What Is, in celebration of the 1900th anniversary of Hadrian’s Wall

Have you ever been to a birthday party for a fortified wall?

Hadrian’s Wall in Britain recently turned 1,900 years old. Its construction began in 122 C.E., when the emperor Hadrian ordered the Roman army to build a wall separating the province Britannia from contested land to the north. Sections of this stone wall still stretch across northern England. To celebrate the anniversary of this innovative landmark, the Hadrian’s Wall Management Board organized a series of special events, including costume parties and a colorful art installation. While these celebrations brought local communities together, excavations have revealed evidence for the people who lived here in antiquity—including soldiers from Europe, North Africa, and West Asia.

Running approximately 73 miles (117 kilometers) from coast to coast, Hadrian’s Wall stands out on maps and in aerial photographs. On site, experiencing the wall takes time: at least a week is needed to walk along the rocky and hilly terrain. The weather here can be cold and rainy, likely a shock for Roman soldiers accustomed to warmer climates. [1]

Rome’s invasion of Britain

Why was an empire based in Italy interested in controlling a region as far north as Britain? Natural resources such as metal deposits drew the attention of Rome’s leaders, as did the personal glory of conquering new territory. The famous Roman general Julius Caesar visited and considered an invasion as early as the 50s B.C.E., but then refocused on completing his conquest of France (Gallia). What he found in Britain were people who spoke Celtic languages and were organized into small competing kingdoms with constantly shifting alliances. Taking advantage of ongoing political divisions, the Roman emperor Claudius ordered the Roman army to invade Britain in 43 C.E. The new Roman province Britannia was established in the lands that we now call England and Wales. Rome’s conquest of neighboring regions was never complete: Ireland always remained free, as did most of Scotland.

Roman rule of Britannia was sometimes violently contested, most famously by queen Boudicca (Boadicea) of the Iceni people. Following abuse by Roman officials, she raised an army and attacked Roman London in the 60s C.E. Other leaders, such as Queen Cartimandua of the Brigantes people, allied themselves with Rome. These two queens were exceptional in their power—most of the island’s leaders were men—but it was common for communities to respond to Rome’s invasion in radically different ways.

Locating Hadrian’s Wall

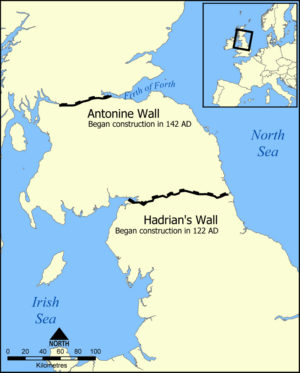

When the Roman emperor Hadrian toured Britannia in 122 C.E., he ordered the construction of the wall that would bear his name. The site chosen was a stretch of land across northern England, where the island narrows. The wall’s location and design discouraged invasions of Britannia from the north, while allowing the Roman army to monitor the circulation of traders and travelers. The wall fortified a frontier, but was not necessarily a political border. Rome sometimes claimed territory farther north, and the modern border between Scotland and England lies farther north, too.

Hadrian’s Wall at Thorny Doors (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Designing Hadrian’s Wall

Hadrian’s Wall was one of the largest architectural projects of the ancient world. The plan for this frontier included not only the wall, but also defensive landscaping, and a network of forts.

The stone wall at the center of the plan has eroded over time, but is thought to have risen as high as 15 feet (4.5 meters), with a width that generally varied between 6 and 10 feet (2 to 3 meters). Deep ditches and mounds ran parallel to the wall to create an obstacle course for anyone trying to cross the border without permission. Authorized crossings were possible through well-guarded gates.

Milecastle 42 (Cawfields), Hadrian’s Wall (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

An artist’s reconstruction of Poltross Burn milecastle on Hadrian’s Wall © Historic England (illustration by Peter Lorimer)

There were eventually sixteen forts built directly along the wall. Ideal spacing between them was 7 miles (11 kilometers), a distance equivalent to a half day’s march, though actual distances varied due to uneven terrain. Between these forts were smaller installations called milecastles. They were spaced a mile apart and between them stood watchtowers called turrets.

Additional freestanding forts stood to the north and south of the defensive landscaping. This layered design allowed for constant surveillance, quick communication, and the rapid deployment of troops. [2]

An unusual frontier

Carole Raddato’s open access photo of reconstructed fence along the German frontier (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Roman empire claimed territory in Europe, North Africa, and West Asia, and each imperial frontier had a different appearance. The one running through Germany (Germania), for instance, made extensive use of wooden fencing.

In comparison, Hadrian’s Wall took the concept of a stone wall encircling a city or fort and applied it to the northern edge of a province that was otherwise surrounded by the sea. Although Hadrian did not leave records describing why he ordered a new defensive system for Britannia, he is famous for sponsoring other ambitious and innovative architectural projects such as his Pantheon in Rome and his Villa at Tivoli.

Community perspectives

The wall’s significance varied among Britannia’s diverse residents. For the soldiers who came from all over the Roman empire to construct and repair the wall and defend its forts, this frontier zone was a place of work, camaraderie, and even family life. Perspectives of the island’s Celtic communities can be difficult to recover due to a lack of written sources, but the wall certainly cut across ancestral lands. Material evidence from the Chesters and South Shields forts helps us imagine the experiences of these different groups.

Chesters Fort (Cilurnum)

Chesters (ancient Cilurnum) had the typical shape of a Roman fort: a rectangle with curved corners. Directly connected to the wall, the fort projected north toward contested territory and south into the Roman province.

Barracks, Chesters Fort, England (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Chesters housed about 500 cavalrymen, including a unit from Roman Spain. [3] In the fort’s northeastern corner are remains of barracks, rows of narrow rooms that resemble modern dormitories. The cavalrymen lived here to deploy quickly through the northern gates.

Left: Juno standing on a heifer, 2nd–3rd century, sandstone, from Chesters Fort; right: figurine of a “Scottie dog,” 2nd–3rd century, copper alloy, found at Chesters Fort, either the south wall or one of the four interval towers (both in the Chesters Roman Forts Collection)

Remains of Hadrian’s Wall descending toward the River North Tyne (photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The belongings that they sometimes left behind are now displayed at the site’s museum, along with finds from nearby forts. Metal adornments and figurines have survived due to their lasting materials, as have stone monuments dedicated to different gods.

Remains of Hadrian’s Wall can still be seen descending toward the River North Tyne. Chesters guarded this vulnerable location, where the river cut across the wall’s defenses. A Roman bridge once stood here so that soldiers could conduct patrols across the water.

Arbeia Fort, measuring 616 by 370 feet (188 by 113 meters) (photo: Kimberly Cassibry, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

South Shields Fort (Arbeia)

Whereas Chesters Fort stood near the center of the island, South Shields Fort (ancient Arbeia) had a strategic location on the frontier’s eastern end. Located where the River Tyne flows into the North Sea, this freestanding fort served as a clearinghouse for the frontier’s supplies.

Sections of South Shields Fort have been reconstructed for visitors. The western gateway has been rebuilt to show its stone archways and towers. The commander’s residence within the fort has been reconstructed to reveal a painted dining room (triclinium) where elite officers and visitors could dine comfortably on cushioned couches. These reconstructions help us imagine what it was like to enter a Roman fort and to live in one. Tombstones preserve the names of the frontier’s residents.

Tombstones for Regina and Victor

Most of the tombstones from the frontier commemorate fallen soldiers, yet an especially lavish one from South Shields Fort honors a woman named Regina, who likely died between 175 and 200 C.E. [4] The relief sculpture shows her seated in a wicker chair, wearing regionally popular clothes and jewelry, and holding sewing equipment in a pose that showcased a woman’s expected skills. Her head is now missing, but probably did not capture Regina’s appearance. Relief sculptures on tombstones often featured generic rather than particular people, with individual identities communicated through inscriptions.

The tombstone’s Latin inscription tells us that Regina was approximately thirty years old when she died and that she was a member of the Celtic Catuvellauni people of southern England. It also tells us that she was the enslaved servant and then the wife of a man named Barates, who set up the monument. Barates was from Palmyra, Syria, and added a phrase of mourning in the Palmyrene language and script just beneath the Latin.

It would be extremely valuable to know what Regina thought of frontier life, but evidence for her own perspective does not survive. Barates likely freed her so that they could marry, but how she became enslaved in the first place remains a mystery. Regina’s story nonetheless reminds us that women were present in the frontier zone and that the identities of Celtic peoples, such as the formerly powerful Catuvellauni, persisted long after Rome’s invasion. [5]

Regina was not the only freedperson commemorated at Arbeia. Another tombstone honors a man named Victor, who came from Rome’s Mauretanian provinces in northwestern Africa. [6] He likely died between 150 and 200 C.E. His tombstone has an architectural frame with pilasters and a triangular pediment. [7] The main relief sculpture shows a man reclining on a banqueting couch, with a servant (perhaps an enslaved one) standing beneath and offering a cup. These figures are a good example of the hierarchy of scale in art, with the more important person (the banqueter) shown in a relatively larger size. Details in this particular scene, such as the carving of the drapery folds, have parallels at Palmyra, and the sculptor may have traveled from that region. Banqueting imagery was common in funerary art and often reflected aspirations rather than reality.

The Latin inscription beneath the figures tells us that Victor was approximately twenty years old when he died. It also indicates that he had been owned and then freed by a man named Numerianus, who served in a cavalry unit from Roman Spain. Given that tombstones were often set up by close friends or loved ones, scholars have wondered if Victor and Numerianus became partners.

These and other tombstones document the complex identities, relationships, and journeys of the people who lived and worked along Hadrian’s Wall. They remind us that enslaved individuals and freedpersons contributed to frontier life, though only a select few were commemorated with luxuriously sculpted monuments.

Electrotype copy of vessel showing Hadrian’s Wall; the copper alloy original was found at Rudge Coppice, England, in 1725, 9 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Commemorating Hadrian’s Wall

Ancient souvenirs from Hadrian’s Wall have been found in northern France and southern England, regions where soldiers retired. These rare mementoes are small metal vessels decorated with colorful enameling that has faded over time. One design (shown above) combines names of the wall’s forts with depictions of a fortified stone wall.

Copper alloy vessel with preserved enamel, mid-2nd century, found in Staffordshire Moorlands, England, 9.4 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

An alternative design survives on an artifact discovered by metal detector in 2003. [8] This composition combines names of the wall’s forts with swirling patterns typical of Celtic aesthetics, which remained popular in Britain for centuries after Roman conquest. [9] These vessels reveal how craftsmen evoked the frontier for those who wished to remember it.

Hadrian’s Wall as heritage

In the early 400s C.E., the Roman empire withdrew from the island because of ongoing land and sea attacks by rival powers. Yet remains of the wall and its forts have endured. Hiking Hadrian’s Wall has become a popular activity, with a well-mapped trail following the wall’s ruins over hills and valleys. Many of the forts along the way, such as Chesters, are managed as tourist destinations by English Heritage. UNESCO even recognizes the entire frontier as a World Heritage site. [10] This is a fascinating fate for a wall that began as a divisive barrier built by invaders.