Livia Drusilla as Priestess (Livia was married to the Roman Emperor Augustus), 2nd quarter of the 1st century C.E. (found at the theatre at Herculaneum), bronze (National Archaeological Museum, Naples, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In the Roman world, art did not exist for art’s sake; rather, art was a way that individuals from the emperor to a freedman (that is a formerly enslaved man) might present himself—or herself—to the world. Images of Roman empresses abound, appearing on coins, in relief and architectural sculpture, in cameos, and other small-scale luxury items. Elite women were often the benefactors of their cities and were honored with sculptural dedications in public spaces. But sculptural reliefs were also a common way that non-elite women, across the empire, articulated their identities and their work. Free-born, freed, and/or enslaved women, like their male counterparts, are well represented in the art—especially funerary reliefs—of the late Republican and Imperial eras (1st century B.C.E. to 3rd century C.E.). Tombs lined the roads leading to and from Roman cities, aiming to attract the attention of passers-by. These reliefs, when interpreted alongside the funerary inscriptions that also adorn many Roman tombs and grave markers, enable us to understand the diverse types of labor that Roman women performed. Wall paintings from Pompeii also depict women working.

The domestic sphere: hairdressers & midwives

Domestic work dominated women’s employment in the Roman world, whether they were enslaved, freedwomen, or, on occasion, free-born. Funerary inscriptions demonstrate that more than 40 percent of women’s jobs were domestic in nature.

Considering the importance of hair as a symbol of status, personal identity, and cultural belonging for Rome’s elite women, it is unsurprising that the hairdresser (ornatrix) was one of the most important and widespread jobs for Roman women. For example, in Ostia, 20 percent of the funerary inscriptions about women note that their jobs were hairdressers. While some of them were attached to a household, other women worked independently. There were also personal attendants (like a lady’s maid), dressers, and masseuses. They were essential in helping elite women cultivate their appearance.

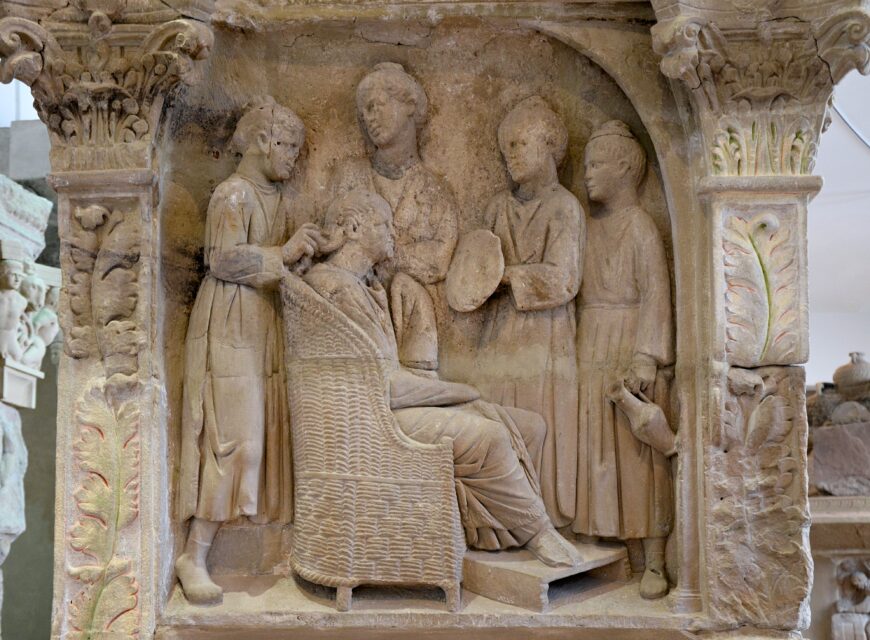

Funerary relief depicting a woman’s hair being dressed by enslaved women, c. 220 C.E. (Neumagen, Germany) (Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A late 2nd-century or early 3rd-century C.E. funerary relief from Neumagen (Germany) depicts a woman at her toilette having her hair done. Seated in a wicker chair with her feet comfortably resting on a low bench, the mistress of the house is attended to by a simply-dressed ornatrix styling her mistress’s hair from behind, while three other women attend to her. One holds a pitcher while another holds a flattened disc which could be a mirror. Another woman looks on, perhaps her dresser. The reliefs that decorated the architectural frame of the scene have traces of pigment (with green on the leaves against a red background) indicating that this relief was once quite colorful. While the mistress’s hair is being tended to, the other three women all have simple buns pulled up on the crown of their heads ensuring that their hair is out of the way. Scholars have argued that the mistress of the house owned these enslaved women rather than her husband, a sign of her financial independence. The relief also helps to see how people—women both free and enslaved—who often don’t appear in the historical record are present in material culture. There is no surviving inscription to tell us more about these individuals, but clearly being shown as mistress of the house was important.

Marble plaque showing parturition scene, 400 B.C.E.–300 C.E. (Ostia, Italy), marble, 25 x 34 x 6.3 cm (Science Museum, London)

Delivering children was also considered women’s work in the Roman world. Midwives (obstetrices), wet nurses (nutrices), and doctors (medicae) could be enslaved in a particular household or could work independently. According to the Digest of Justinian, a compilation of legal texts published in the 6th century C.E. (7.7.1.5a), enslaved people with medical training had a high value, regardless of gender. Certain doctors or midwives were valued because they had expertise in women’s health and obstetrics. While many scenes depict women seated upright on a birthing chair (to take advantage of gravity), this scene, from Isola Sacra (near Ostia), shows a woman lying on her back while in the process of giving birth. Her face is serious and she looks directly at the mid-wife who is assisting her. She has already given birth to one child, who is being held on a cushion with a blanket at the left of the scene. She may be giving birth to a second child. We do not know if this relief commemorated the midwife, who appears prominently, or the woman giving birth.

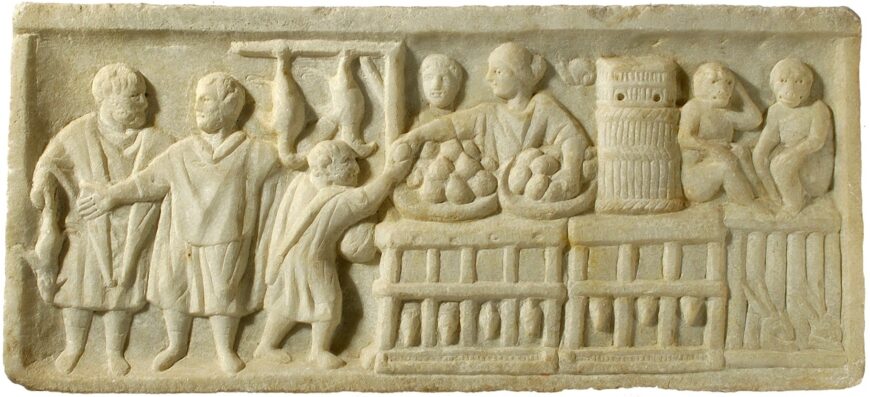

Relief with market scene, 2nd century C.E., marble, 21 x 54 cm (Museum Ostienese, Ostia)

Shop keepers

Outside the home, we know that women also worked in markets, as well as at inns and taverns. Ostia is filled with reliefs depicting women at work. A 2nd-century C.E. relief from the Via della Foce focuses on a woman who is selling vegetables, poultry, and rabbits (some of whom are still alive and visible in cages) while her pet monkeys look on.

Women working in a fullonica from the so-called Fullonica di Veranius Hypsaeus (VI.8.20), Pompeii, pre-79 C.E. (National Archaeological Museum, Naples)

Women also engaged in manual labor. For example, they appear cleaning and working cloth at a fullonica, or fullery (VI.8.20), in Pompeii. A fullonica was an establishment where cloth was laundered, but also where workers may have prepared cloth (for example by dying it) before it was sold. This wonderful wall painting, now in the Archaeological Museum in Naples, shows—in vivid color—how women contributed to the Roman economy. Wall paintings provide another important source of evidence for women and their labor in the Roman world.

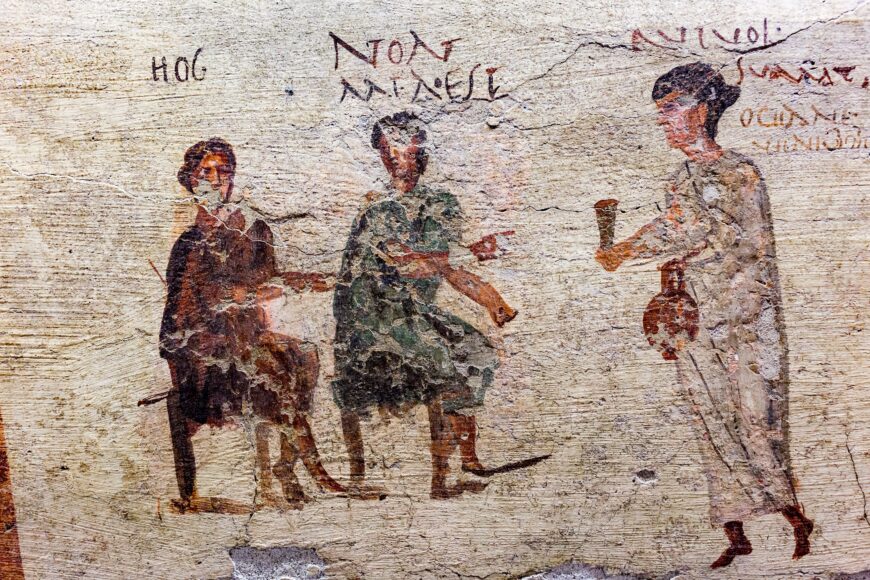

A barmaid, fresco from the so-called bar (caupona) of Salvius (VI.14.36), Pompeii, pre-79 C.E. (National Archaeological Museum, Naples)

Other occupations: sex workers & gladiators

Women also held other less reputable or lower-status jobs in the Roman world. Women worked as wait staff at bars and inns, but the ancient sources also report that such women were also available for sex—at a price—to their establishment’s clients. In this fresco from the bar (caupona) of Salvius (VI.14.36) a barmaid carries not only a mug, but a large pitcher (lagona) of wine to the bar’s patrons. The fresco’s Latin inscription (CIL IV 3494) brings humor and levity to the scene. Reading from left to right, one man says, “Over here (hoc);” while the one on the right says, “No, It’s mine! (Non mia est)” The barmaid, exasperated by their bickering, replies, “Whoever wants it should take it. Oceanus, come here and drink! (Qui vol sumat oceane veni bibe).” [1]

Contemporary male authors also viewed female singers and dancers as sex workers by another name. Sex workers do appear in the archaeological record (there was in fact a purpose-built brothel in Pompeii).

Two Female Gladiators (Achilia and Amazon), 1st–2nd century C.E. (found at Halicarnassus), marble (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Women could even be gladiators. The ancient sources again note that women fought as gladiators, and Roman emperors periodically banned female gladiators from fighting in the arena. A marble relief from Halicarnassus (in modern-day Turkey) depicts two female gladiators, named Amazon and Achilia (their names appear in Greek below the relief on a block). While scholars debate precisely what this scene shows, they are armed and ready to strike. Each bearing swords and shields, they are dressed identically to male gladiators but they both lack helmets. The right figure’s head has not survived. Their arms are wrapped in straps and the fighter on the right seems to pull her left arm back, ready to land a blow. Spectators appear on both sides of the block, peering up at their combat.

The names of these two gladiators, Amazon and Achilia, may refer to a mythic ancient Greek battle between the Greeks and the Amazons (mythological female warriors), a subject that appears frequently in ancient Greek art (including on the Parthenon). As scholars have noted, battles between female gladiators might have been viewed as a reenactment of mythological battles that Romans enjoyed.

While we lack the voices of many people from the Roman world, these funerary reliefs—both their images and words—help us to understand the vibrant role that women played in the Roman economy and the daily lives of women across the Roman world.