James Bamba, Guagua’ (basket), 2016 (Guam), coconut palm leaf (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington) © James Bamba

Present-day Chamorus, the Indigenous people of the Mariana Islands (Guåhan [Guam], Luta [Rota], Tinian, and Saipan), own businesses, are social media influencers, and run cultural organizations that often feature tinifok (pieces that are woven) as a celebrated part of our Chamoru cultural identity. In 2023, for instance, fundraisers for typhoon relief in the Mariana Islands included social media posts from weavers selling gold hoop earrings meticulously woven in åkgak (pandanus leaves) to those living within the archipelago and in our diaspora. Posted images of tinifok tuhong (woven hats) created from hågon niyok (coconut leaves) invite viewers to join classes to learn new mamfok (weaving) techniques while also practicing fino’ Chamoru (the Chamoru language). Weaving has been an essential part of Chamoru life for millennia, and while its utilitarian usage for daily life has shifted to more artistic expressions, it remains a critical part of Chamoru material culture. In order to understand the importance of weaving within the Mariana Islands, a wider look at Micronesia highlights a region known for its strong weaving practices.

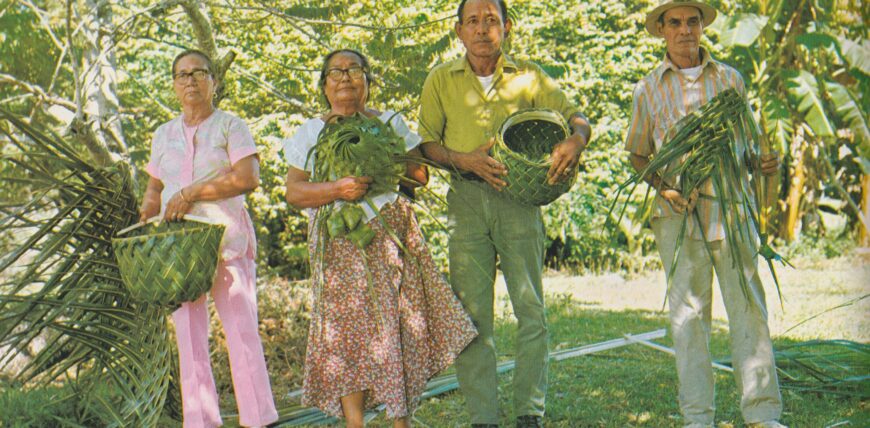

Chamoru weavers from Lanchon Antigu, formerly in the village of Inalåhan, Guåhan (Guam Museum, a division of the Department of Chamorro Affairs, Hagåtña)

Weaving in Micronesia

Micronesian weaving traditions reflect the richness of textile practices throughout all of Oceania and its subregions (Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia). The various climates, plants, and cultures of Micronesia’s over 2,000 islands make for an array of unparalleled artistry and technical skills in weaving practices. Weaving involves the use of natural materials such as leaves and fibers from coconut, palm, bamboo, banana, hibiscus, or pandanus trees. Micronesian woven pieces are highly valued because of their connections with the environment and family genealogies. Worn with pride and prestige, they often fulfill a symbolic role as crucial items for cultural ceremonies and as ways to communicate social and political power. Woven items are revered for their practical use and durability, may be understood as indicators of wealth, and continue to be exchanged among Micronesian communities worldwide.

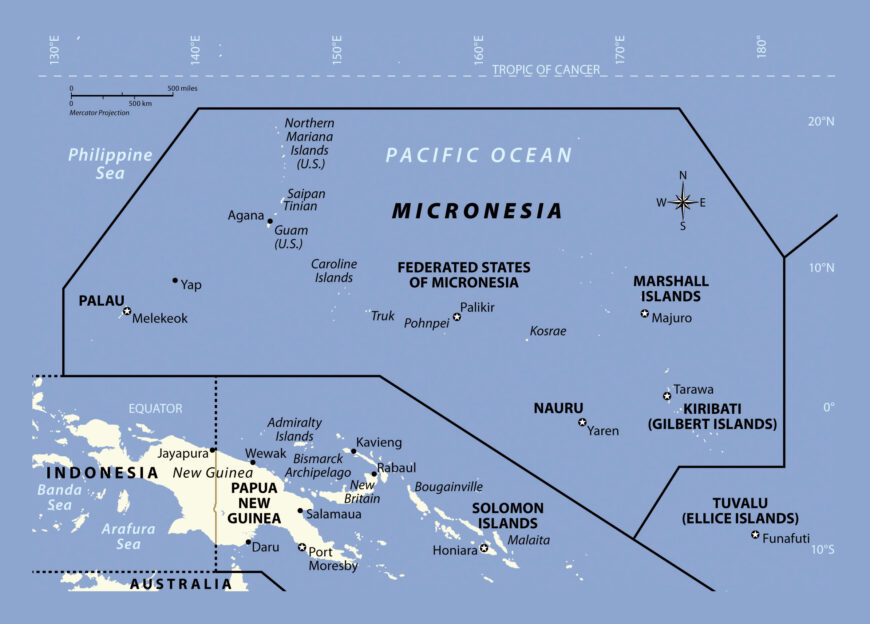

Map of the Micronesia region and its island nations (Mapsland, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Traditional pandanus sail woven by master weaver of Lamotrek, Maria Labusheilam, her daughter Maria Ilourutog, and twenty apprentices (photo: Jesi Lujan Bennett, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Women are often the weavers in Micronesia and their skills and artistry were and continue to be seen in most facets of life, including sails for canoes, mats to sit and sleep on, containers to meet daily needs, and clothing to protect and adorn the body. For example, women in Chuuk, Yap, Pohnpei, Kosrae, and the Marshall Islands use banana stalk fibers and hibiscus tree bark to create cloth through loom weaving. The cloth typically has intricate geometric designs and decorative shell elements that a weaver will incorporate depending on the occasion or significance of the woven work. In Pohnpei, large tor (sashes worn by high-ranking men) are created with a backstrap loom using banana fiber that are woven with complex designs and patterns that are connected to particular families who have the sole right to wear them. These designs are so highly prized and significant that they are also reflected in Pohnpeian tattoo motifs. Together, woven cloths and tattoos signify the wearer’s genealogy, social rank, and other identity markers.

Weavers, Lia Barcinas and Martha Tenorio, of Guåhan creating a guagua’ together (photo: Lia Barcinas, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Colonial and environmental impacts on guagua’

Guagua’ are widely known as woven baskets made from coconut leaves and used by fishermen to securely hold their catch. Chamoru weavers understand guagua’ to be a specific type of double rimmed basket style made by experienced hands. The creation of this type of vessel is labor-intensive, using both sides of the coconut frond in a complicated pattern to ensure an extremely strong, durable, reinforced, and hardwearing base.

Bottom and top views of the distinct double-rimmed style of guagua’ woven by James Bamba, 2016 (Guam), coconut palm leaf (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington) © James Bamba

Some weavers prefer a particular leaf count, while others use the number of leaves provided by the branch. Regardless of preference, these skilled hands will use more than twenty leaves to complete the basket. Today the expertise needed to make this intricate basket style is hard to come by, and finding healthy, identical leaves is almost as difficult.

The usage and availability of guagua’ have transformed over time for Chamoru people with restrictions imposed by colonial powers, such as Spain, Japan, Germany, and the United States. These colonial waves changed the tide of our political histories as well as our relationships to tinifok by enforcing strict assimilationist restrictions that were often in conflict with Chamoru cultural heritage and expression. Plants required for weaving guagua’ are now harder to find, especially in Mariana Islands’ largest island, Guåhan. The ability for weavers to make guagua’ is crucially impacted by the vulnerability of coconut trees to introduced diseases and invasive species, the mismanagement of natural resources, and environmental degradation attributed to impacts of the U.S. military within the Mariana Islands.

Weaver, Roquin-Jon Quichocho Siongco, wearing his woven tuhong (photo: Michael Torres, courtesy of Roquin-Jon Quichocho Siongco, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Chamoru weaving (mamfok)

In the Mariana Islands, mamfok played an important role in daily life for Chamoru people and a multitude of plants were used to create everyday goods. Åkgak takes substantial preparation before it can be woven. The edge of the leaf must have its sharp thorns stripped. It is then boiled and scraped before being dried in the sun. Once dried, the leaf is rolled and left in the sun again to cure. Hågon niyok, hågon nipa (native palm), piao (bamboo), and pågu (hibiscus tree) are also widely available and strong options for tinifok. Weavers used these various types of leaves to create dogga (shoes) and tuhong (hats) as physical protection from the ocean, jungle, and mountainous terrain.

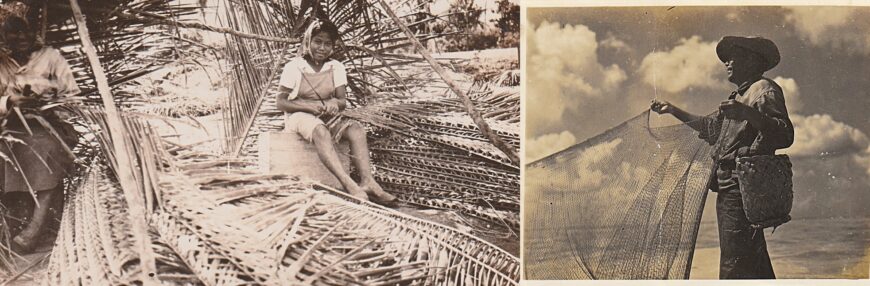

Left: Chamoru woman helping weave a thatch roof in 1945; right: Man fishing with a talaya and wearing a guagua’ on his hip (both: Guam Museum, a division of the Department of Chamorro Affairs, Hagåtña)

They made guåfak (mats) for sleeping, funerary needs, floor mats, and to dry crops on. Baskets and boxes were also essential to daily life; complexly woven containers were made in different shapes and sizes, often with straps and lids. Saluu (specialized plaited boxes) were made with latches and served as containers for pugua (betel nut). The imagination and skills of a weaver enabled them to create whatever the family needed, including thatched roofs, talaya (fishing net), and fagapsan (baby cradles). There were no limitations as long as the leaves were available.

Guagua’ and sovereign futures?

For generations, mamfok was a common skill for most Chamoru people. Children learned how to mamfok by observing their family members make woven pieces used for daily tasks, such as katupat, a woven pouch for carrying food items like rice. Following World War II, there was a sharp decline in the number of weavers because of the introduction of American household goods that replaced the need for woven goods for many Chamoru families. Nevertheless, mamfok remains an important part of our cultural contexts and continues to be a valued element of our island traditions. Starting in the 1960s, an artistic revival and celebration of our cultural practices coincided with the growth of Chamoru political self-determination and wider movement of decolonization throughout Oceania. In Guåhan, new government agencies led by Chamorus (e.g., Chamorro Language Commission) created projects that helped to revitalize and promote our arts, traditions, and language. Movement towards a decolonial future was closely aligned with a reclamation of Chamoru cultural heritage.

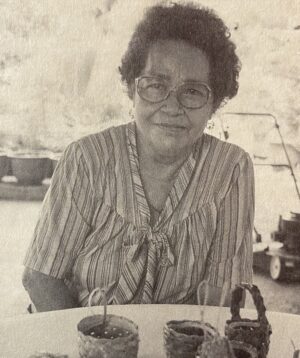

Lucia Fernandez Torres, the first Chamoru to be awarded the Master of Traditional Arts (Guam Museum, a division of the Department of Chamorro Affairs, Hagåtña)

Our celebrated master weavers leave lasting legacies by training the next generation of weavers and generously sharing their skills as knowledge holders. For example, Lucia Fernandez Torres was the first Chamoru to be awarded the Master of Traditional Arts in 1989 and Maga’lahi (Governor) Art Award in Special Recognition for Lifetime Cultural Contributions in 1997. In 1976, Elena Cruz Benavente represented Guåhan at the Festival of the Pacific Arts (FESTPAC) in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and she was twice awarded the Maga’lahi Art Award for Lifetime Cultural Achievement as a master artist, in 1989 and 1991. In 1997, the Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (CAHA) in Guåhan formally recognized Floren Meno Paulino as a Master Weaver for her skills and participation in cultural events in and beyond Micronesia.

Similarly, in 1988 Tan Dolores Flores Paulino represented Guåhan in FESTPAC in Australia and CAHA later recognized her as a Master of Chamoru Culture for tinifok åkgak (woven pandanus). These enduring practices serve as powerful symbols of cultural knowledge and pride for many Chamoru in the contemporary context.

Left: Miniature katupat made into a necklace and earring set (photo: Lia Barcinas, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); center: Lia, Rita, and Arisa Barcinas, woven hammerhead sharks and Chamoru legendary mermaid, Sirena (photo: Jesi Lujan Bennett, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Roquin-Jon Quichocho Siongco wearing their woven design for their drag persona, Sin Amen (photo: Roldy Aguero Ablao, courtesy of Roquin-Jon Quichocho Siongco, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In the 2020s, generations of Chamoru weavers, such as the Barcinas sisters (Lia, Rita, and Arisa) extend understandings of traditional woven goods, such as a katupat, to create novel forms like miniature versions that adorn earrings. They also create sculptural works, such as hammerhead sharks, bringing new artistry to mamfok. As a member of the queer, interdisciplinary Chamoru art collective, Guma’ Gela’, “Rockin Roquin” (Roquin-Jon Quichocho Siongco) weaves one-of-a-kind pieces that Indigenize the contemporary fashion landscape. Roquin’s work has graced runways from London, England, to Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), Aotearoa (New Zealand). Mamfok in its modern forms are also celebrated and expressed in digital spaces and social media sites that communicate ongoing intimate relationships between Chamoru people and their natural environments and weaves connections among Chamoru diasporic communities worldwide. Mamfok represents the ability to thrive despite colonial and environmental shifts in the Mariana Islands. In spite of these complex issues, contemporary cultural practitioners continue to push mamfok to be multifaceted as cultural, sculptural, and artistic forms that are relevant for Chamoru lived experiences today.