Rapa Nui moai cast in the Pacific Galleries of the American Museum of Natural History, NYC, made during the 1934–45 AMNH expedition to Rapa Nui

Essay by The British Museum

View of the northeast of the exterior slopes of the quarry, with several moai on the slopes, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), photo by Katherine Maria Routledge, c. 1914–15, 8.2 x 8.2 cm, lantern slide (photograph) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The moai of Rapa Nui

Easter Island is famous for its stone statues of human figures, known as moai (meaning “statue”). The island is known to its inhabitants as Rapa Nui. The moai were probably carved to commemorate important ancestors and were made from around 1000 C.E. until the second half of the seventeenth century. Over a few hundred years the inhabitants of this remote island quarried, carved and erected around 887 moai. The size and complexity of the moai increased over time, and it is believed that Hoa Hakananai’a dates to around 1200 C.E. It is one of only fourteen moai made from basalt, the rest are carved from the island’s softer volcanic tuff. With the adoption of Christianity in the 1860s, the remaining standing moai were toppled.

Three views of Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1200 C.E., 242 x 96 x 47 cm, basalt (missing paint, coral eye sockets, and stone eyes), likely made in Rano Kao, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), found in the ceremonial center Orongo (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Moai Hava (“Dirty statue” or “to be lost”), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1100–1600 C.E., 156 cm high, basalt, Rapa Nui (Easter Island) (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Their backs to the sea

This example was probably first displayed outside on a stone platform (ahu) on the sacred site of Orongo, before being moved into a stone house at the ritual center of Orongo. It would have stood with giant stone companions, their backs to the sea, keeping watch over the island. Its eyes sockets were originally inlaid with red stone and coral and the sculpture was painted with red and white designs, which were washed off when it was rafted to the ship, to be taken to Europe in 1869. It was collected by the crew of the English ship HMS Topaze, under the command of Richard Ashmore Powell, on their visit to Easter Island in 1868 to carry out surveying work. Islanders helped the crew to move the statue, which has been estimated to weigh around four tons. It was moved to the beach and then taken to the Topaze by raft.

The crew recorded the islanders’ name for the statue, which is thought to mean “stolen or hidden friend.” They also acquired another, smaller basalt statue, known as Moai Hava, which is also in the collections of the British Museum.

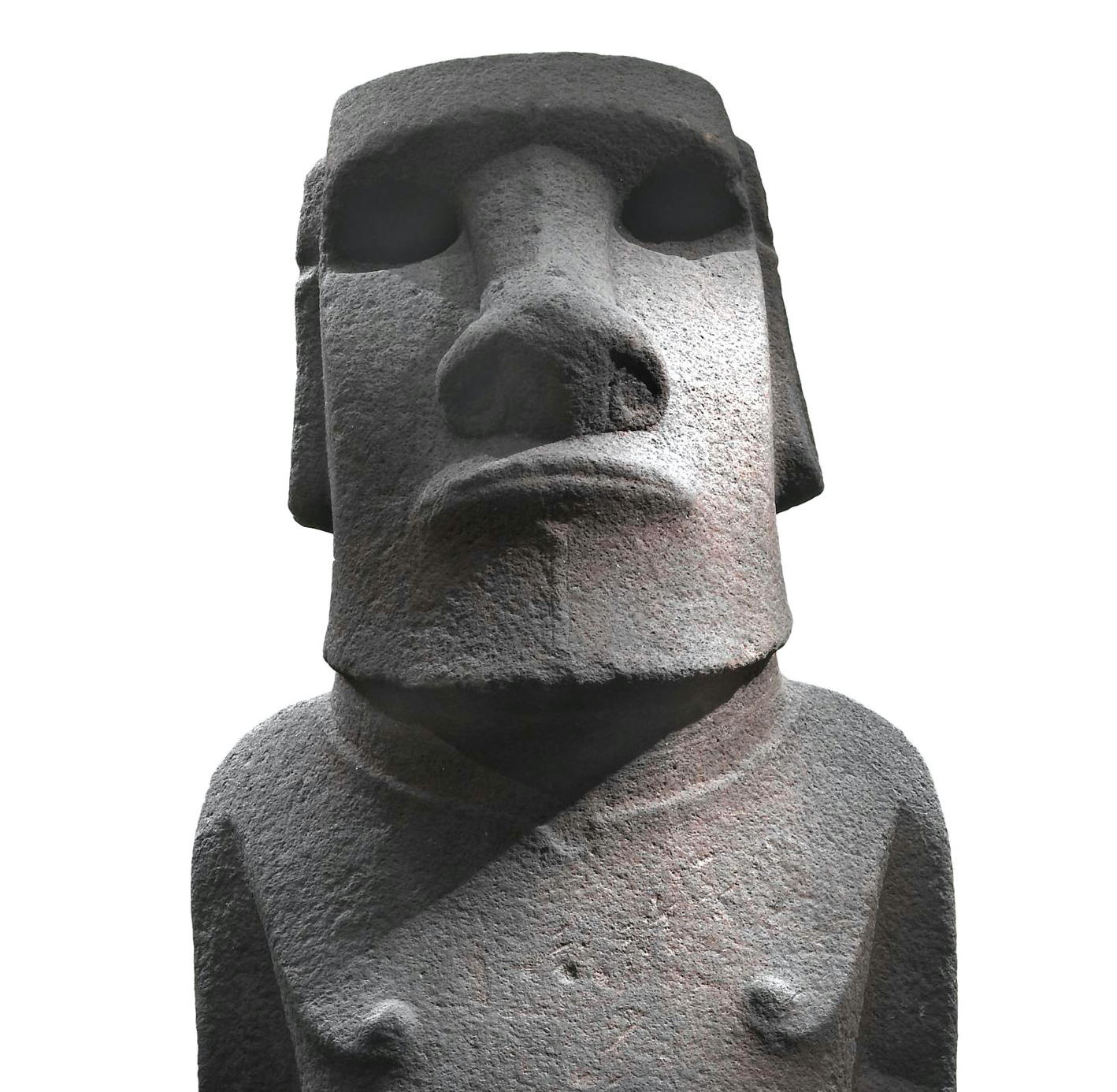

Hoa Hakananai’a is similar in appearance to a number of Easter Island moai. It has a heavy eyebrow ridge, elongated ears and oval nostrils. The clavicle is emphasized, and the nipples protrude. The arms are thin and lie tightly against the body; the hands are hardly indicated.

Bust (detail), Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1200 C.E., 242 x 96 x 47 cm, basalt (missing paint, coral eye sockets, and stone eyes), likely made in Rano Kao, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), found in the ceremonial center Orongo (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1200 C.E., 242 x 96 x 47 cm, basalt (missing paint, coral eye sockets, and stone eyes), likely made in Rano Kao, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), found in the ceremonial center Orongo (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

In the British Museum, the figure is set on a stone platform just over a meter high so that it towers above the visitor. It is carved out of dark grey basalt—a hard, dense, fine-grained volcanic rock. The surface of the rock is rough and pitted, and pinpricks of light sparkle as tiny crystals in the rock glint. Basalt is difficult to carve and unforgiving of errors. The sculpture was probably commissioned by a high status individual.

Hoa Hakananai’a’s head is slightly tilted back, as if scanning a distant horizon. He has a prominent eyebrow ridge shadowing the empty sockets of his eyes. The nose is long and straight, ending in large oval nostrils. The thin lips are set into a downward curve, giving the face a stern, uncompromising expression. A faint vertical line in low relief runs from the centre of the mouth to the chin. The jawline is well defined and massive, and the ears are long, beginning at the top of the head and ending with pendulous lobes.

The figure’s collarbone is emphasized by a curved indentation, and his chest is defined by carved lines that run downwards from the top of his arms and curve upwards onto the breast to end in the small protruding bumps of his nipples. The arms are held close against the side of the body, the hands rudimentary, carved in low relief.

Back of head (detail), Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1200 C.E., 242 x 96 x 47 cm, basalt (missing paint, coral eye sockets, and stone eyes), likely made in Rano Kao, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), found in the ceremonial center Orongo (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Later carving on the back

The figure’s back is covered with ceremonial designs believed to have been added at a later date, some carved in low relief, others incised. These show images relating to the island’s birdman cult, which developed after about 1400 C.E. The key birdman cult ritual was an annual trial of strength and endurance, in which the chiefs and their followers competed. The victorious chief then represented the creator god, Makemake, for the following year.

Back (detail), Hoa Hakananai’a (‘lost or stolen friend’), Moai (ancestor figure), c. 1200 C.E., 242 x 96 x 47 cm, basalt (missing paint, coral eye sockets, and stone eyes), likely made in Rano Kao, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), found in the ceremonial center Orongo (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Carved on the upper back and shoulders are two birdmen, facing each other. These have human hands and feet, and the head of a frigate bird. In the centre of the head is the carving of a small fledgling bird with an open beak. This is flanked by carvings of ceremonial dance paddles known as ‘ao, with faces carved into them. On the left ear is another ‘ao, and running from top to bottom of the right ear are four shapes like inverted ‘V’s representing the female vulva. These carvings are believed to have been added at a later date.

Collapse

Around 1500 C.E. the practice of constructing moai peaked, and from around 1600 C.E. statues began to be toppled, sporadically. The island’s fragile ecosystem had been pushed beyond what was sustainable. Over time only sea birds remained, nesting on safer offshore rocks and islands. As these changes occurred, so too did the Rapanui religion alter—to the birdman religion.

This sculpture bears witness to the loss of confidence in the efficacy of the ancestors after the deforestation and ecological collapse, and most recently a theory concerning the introduction of rats, which may have ultimately led to famine and conflict. After 1838 at a time of social collapse following European intervention, the remaining standing moai were toppled.

© Trustees of the British Museum