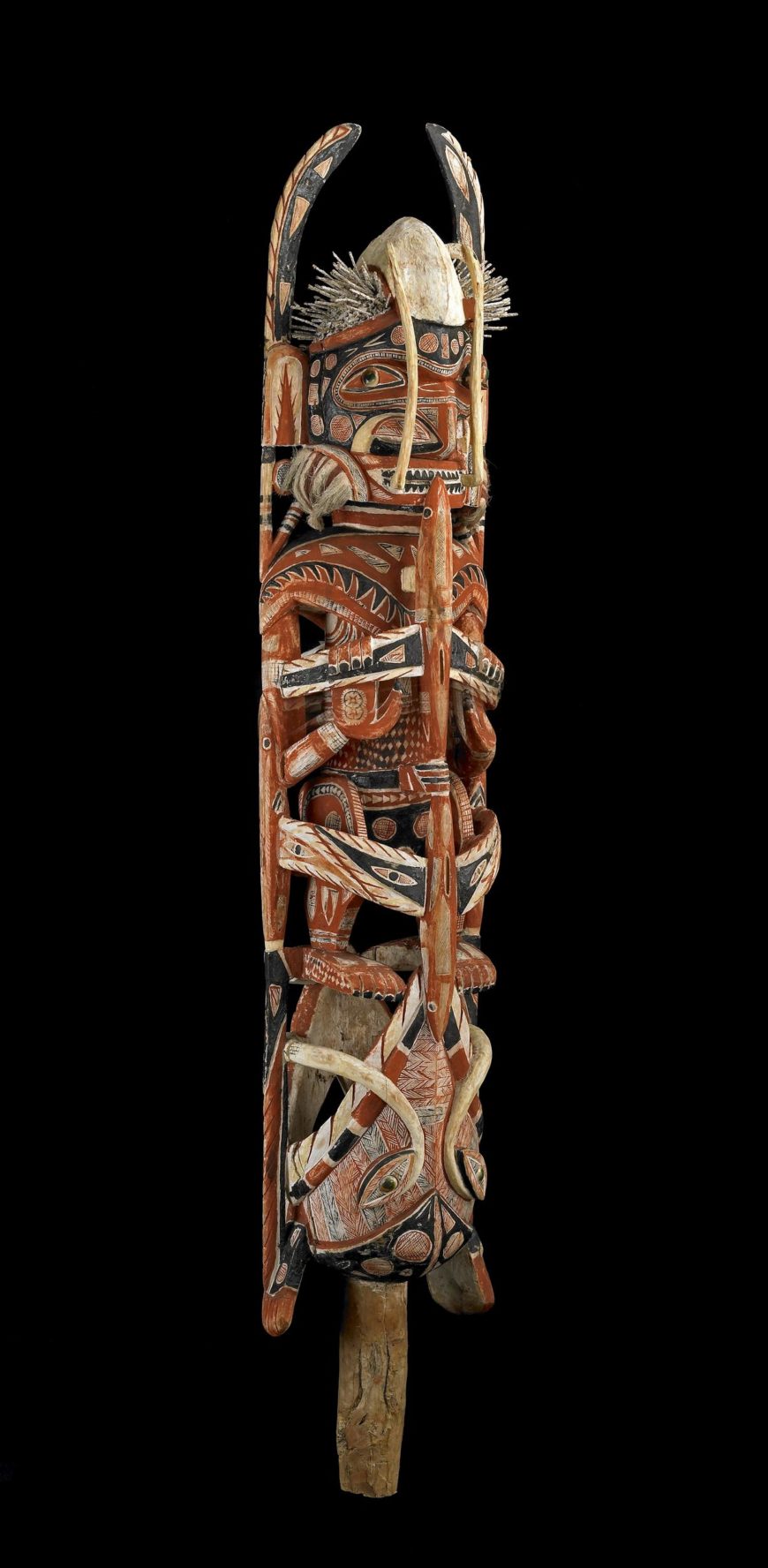

Malangan figure (detail), 1882–83 C.E., wood, vegetable fiber, pigment, and shell (turbo petholatus opercula), 122 cm high, north coast of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Malangan figure

Malangan figure, 1882–83 C.E., wood, vegetable fiber, pigment, and shell (turbo petholatus opercula), 122 cm high, north coast of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (© Trustees of the British Museum)

This figure was made for malangan (also spelled malagan or malanggan), a cycle of rituals of the people of the north coast of New Ireland, an island in Papua New Guinea. Malangan expresses many complex religious and philosophical ideas. They are principally concerned with honoring and dismissing the dead, but they also act as an affirmation of the identity of clan groups, and negotiate the transmission of rights to land. Malangan sculptures were made to be used on a single occasion and then destroyed. They are symbolic of many important subjects, including identity, kinship, gender, death, and the spirit world. They often include representations of fish and birds of identifiable species, alluding both to specific myths and the animal’s natural characteristics. For example, at the base of this figure is depicted a rock cod, a species which as it grows older changes gender from male to female. The rock cod features in an important myth of the founding of the first social group, or clan, in this area; thus, the figure also alludes to the identity of that clan group.

This figure was collected by Hugh Hastings Romilly, Deputy Commissioner for the Western Pacific, while he was on a tour of New Ireland in 1882–83. It was one of a group of carvings made to be displayed at a particular malangan ritual. It is made of wood, vegetable fiber, pigment, and shell (turbo petholatus opercula). They were originally standing in a carved canoe, which unfortunately Romilly did not collect. The whole group was presented to the British Museum by the Duke of Bedford in 1884, after Romilly had sent it to him.

Malangan figures, 1882–83 C.E., wood, vegetable fiber, pigment, and shell (turbo petholatus opercula), north coast of New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Malangan mask

Malangan mask, before 1884, wood, pigment, vegetable fibre, operculum., 48.3 x 79.7 x 49.5 cm, New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Malangan masks are commonly used at funeral rites, which both bid farewell to the dead and celebrate the vibrancy of the living. The masks can represent a number of things: dead ancestors, ges (the spiritual double of an individual), or the various bush spirits associated with the area.

The ownership of Malangan objects is similar to the modern notion of copyright; when a piece is bought, the seller surrenders the right to use that particular Malangan style, the form in which it is made, and even the accompanying rites. This stimulates production, as more elaborate variations are made to replace the ones that have been sold.

Malangan ceremonies became extremely expensive affairs, taking into account the costs of the accompanying feasting. As a result, the funeral rites could take place months after a person had died. In some circumstances, the ceremony would have been held for several people simultaneously.

© The Trustees of the British Museum