Polynesian history and culture

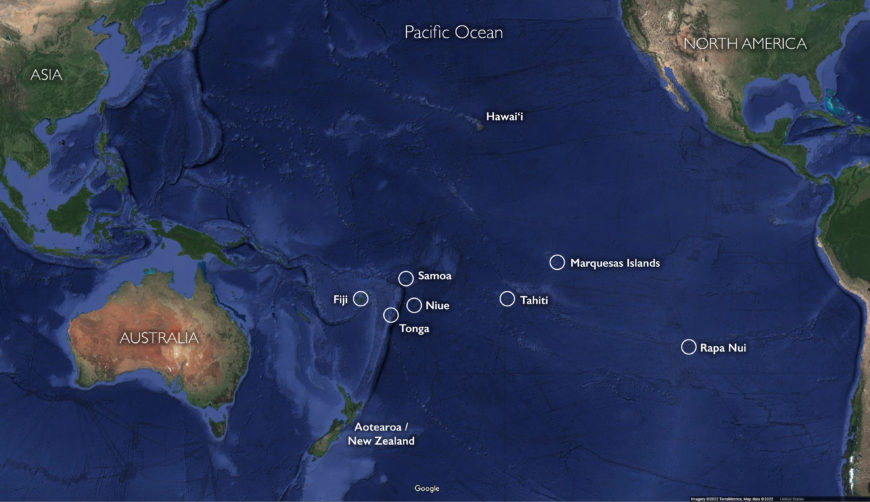

Polynesia is one of the three major categories created by Westerners to refer to the islands of the South Pacific. Polynesia means literally “many islands.” Knowledge of ancient Polynesian culture derives from ethnographic journals, missionary records, archaeology, linguistics, and oral traditions. Polynesians represent vital art-producing cultures in the present day.

Each Polynesian culture is unique, yet the peoples share some common traits. Polynesians share common origins as Austronesian speakers (Austronesian is a family of languages). The first known inhabitants of this region are called the Lapita peoples. Polynesians were distinguished by long-distance navigation skills and two-way voyages on outrigger canoes. Native social structures were typically organized around highly developed aristocracies, and beliefs in primo-geniture (priority of the first-born). At the top of the social structure were divinely sanctioned chiefs, nobility, and priests. Artists were part of a priestly class, followed in rank by warriors and commoners.

Polynesian cultures value genealogical depth, tracing one’s lineage back to the gods. Oral traditions recorded the importance of genealogical distinction, or recollections of the accomplishments of the ancestors. Cultures held firm to the belief in mana, a supernatural power associated with high rank, divinity, maintenance of social order and social reproduction, as well as an abundance of water and fertility of the land. Mana was held to be so powerful that rules or taboos were necessary to regulate it in ritual and society. For example, an uninitiated person of low rank would never enter in a sacred enclosure without risking death. Mana was believed to be concentrated in certain parts of the body and could accumulate in objects, such as hair, bones, rocks, whale’s teeth, and textiles.

Gender roles in the arts

Gender roles were clearly defined in traditional Polynesian societies. Gender played a major role, dictating women’s access to training, tools, and materials in the arts. For example, men’s arts were often made of hard materials, such as wood, stone, or bone and men’s arts were traditionally associated with the sacred realm of rites and ritual.

Hawaiian kapa (barkcloth), 1770s, 64.5 x 129 cm (Te Papa, New Zealand)

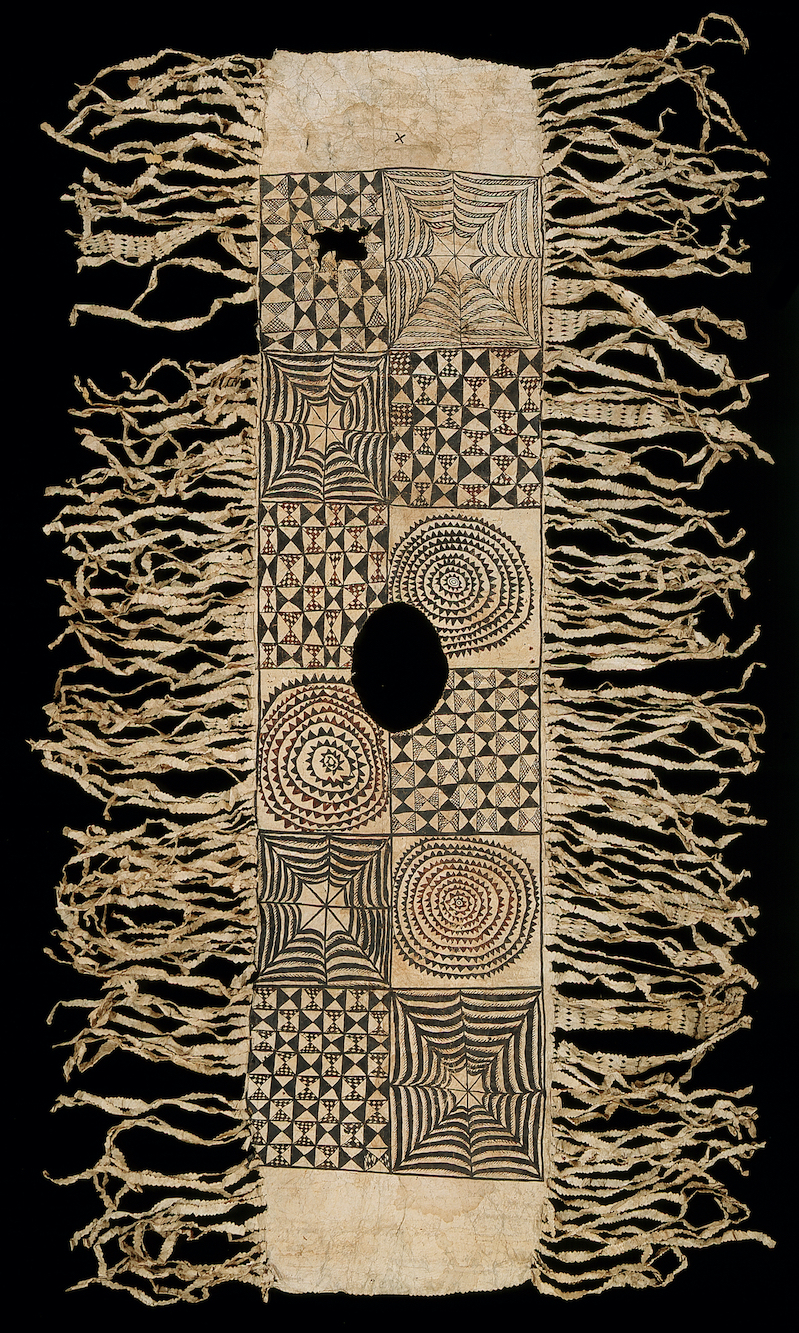

Women’s arts historically utilized soft materials, particularly fibers used to make mats and bark cloth. Women’s arts included ephemeral materials such as flowers and leaves. Cloth made of bark is generically known as tapa across Polynesia, although terminology, decorations, dyes, and designs vary through out the islands.

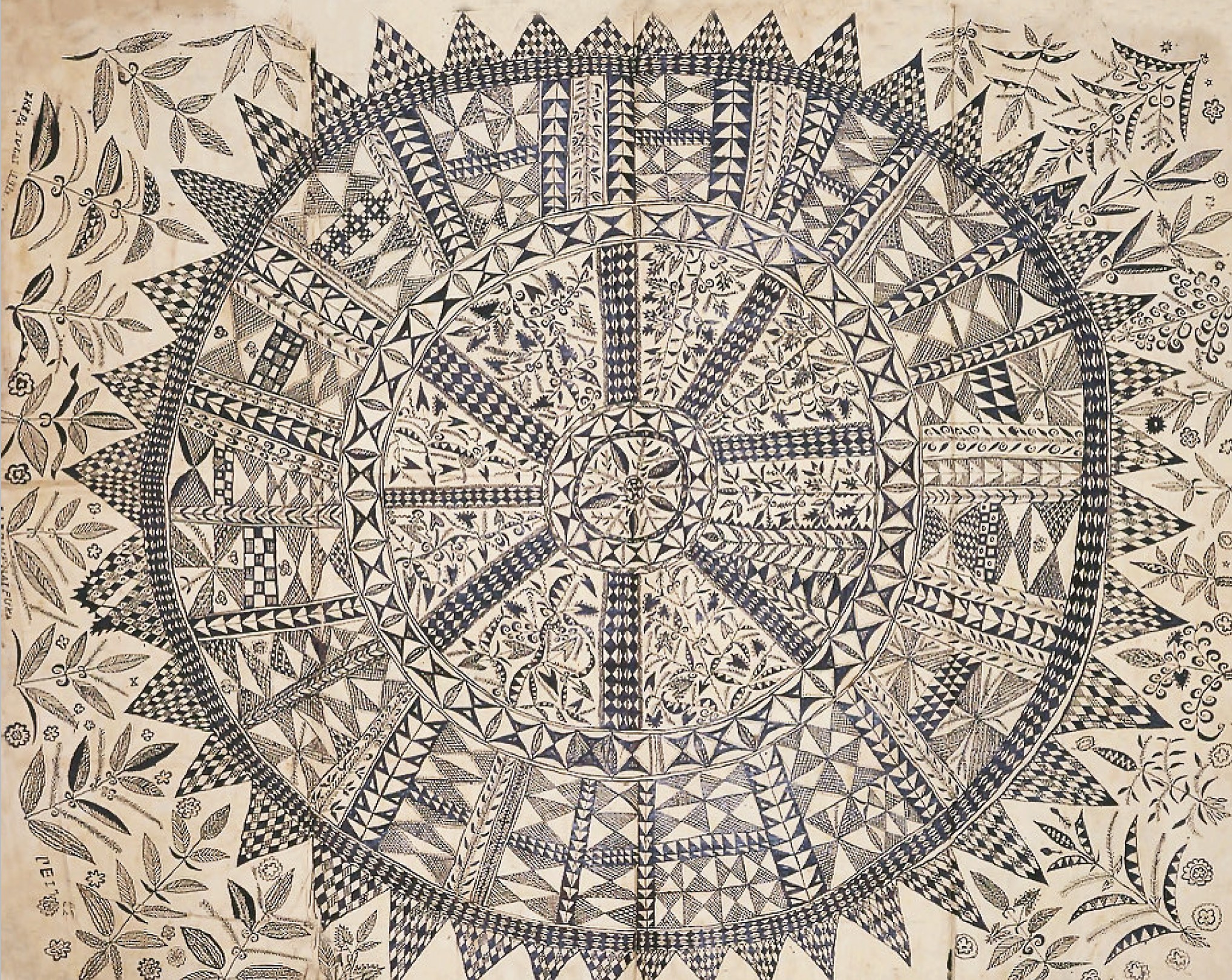

Barkcloth Panel (Siapo), Samoa, early 20th century, 139.7 x 114.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Bark cloth as women’s art

Generally, to make bark cloth, a woman would harvest the inner bark of the paper mulberry (a flowering tree). The inner bark is then pounded flat, with a wooden beater or ike, on an anvil, usually made of wood. In Eastern Polynesia (Hawaiʻi), bark cloth was created with a felting technique and designs were pounded into the cloth with a carved beater. In Samoa, designs were sometimes stained or rubbed on with wooden or fiber design tablets. In Hawaiʻi patterns could be applied with stamps made out of bamboo, whereas stencils of banana leaves or other suitable materials were used in Fiji. Bark cloth can also be undecorated, hand decorated, or smoked as is seen in Fiji. Design illustrations involved geometric motifs in an overall ordered and abstract patterns.

The most important traditional uses for tapa were for clothing, bedding and wall hangings. Textiles were often specially prepared and decorated for people of rank. Tapa was ceremonially displayed on special occasions, such as birthdays and weddings. In sacred contexts, tapa was used to wrap images of deities. Even today, at times of death, bark cloth may be integral part of funeral and burial rites.

Barkcloth strip, Fiji, c. 1800–50, worn as a loin cloth, decorated with a combination of free-hand painting, cut out stencils and by being laid over a patterned block and rubbed with pigment (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

In Polynesia, textiles are considered women’s wealth. In social settings, bark cloth and mats participate in reciprocity patterns of cultural exchange. Women may present textiles as offerings in exchange for work, food, or to mark special occasions. For example, in contemporary contexts in Tonga, huge lengths of bark cloth are publicly displayed and ceremoniously exchanged to mark special occasions. Today, western fabric has also been assimilated into exchange practices. In rare instances, textiles may even accumulate their own histories of ownership and exchange.

Hiapo (tapa), Niue, c. 1850–1900, Tapa or bark cloth, freehand painting (Aukland War Memorial Museum)

Hiapo: Niuean bark cloth

Tiputa (Poncho), 19th century, Niue (Te Papa, New Zealand, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Niue is an island country south of Samoa. Little is known about early Niuean bark cloth or hiapo, as represented by the illustration depicted below. Niueans’ first contact with the west was the arrival of Captain Cook, who reached the island in 1774. No visitors followed for decades, not until 1830, with the arrival of the London Missionary Society. The missionaries brought with them Samoan missionaries, who are believed to have introduced bark cloth to Niue from Samoa. The earliest examples of hiapo were collected by missionaries and date to the second half of the nineteenth century. Niuean ponchos (tiputa) collected during this era, are based on a style that had previously been introduced to Samoa and Tahiti. It is probable, however, that Niueans had a native tradition of bark cloth prior to contact with the West.

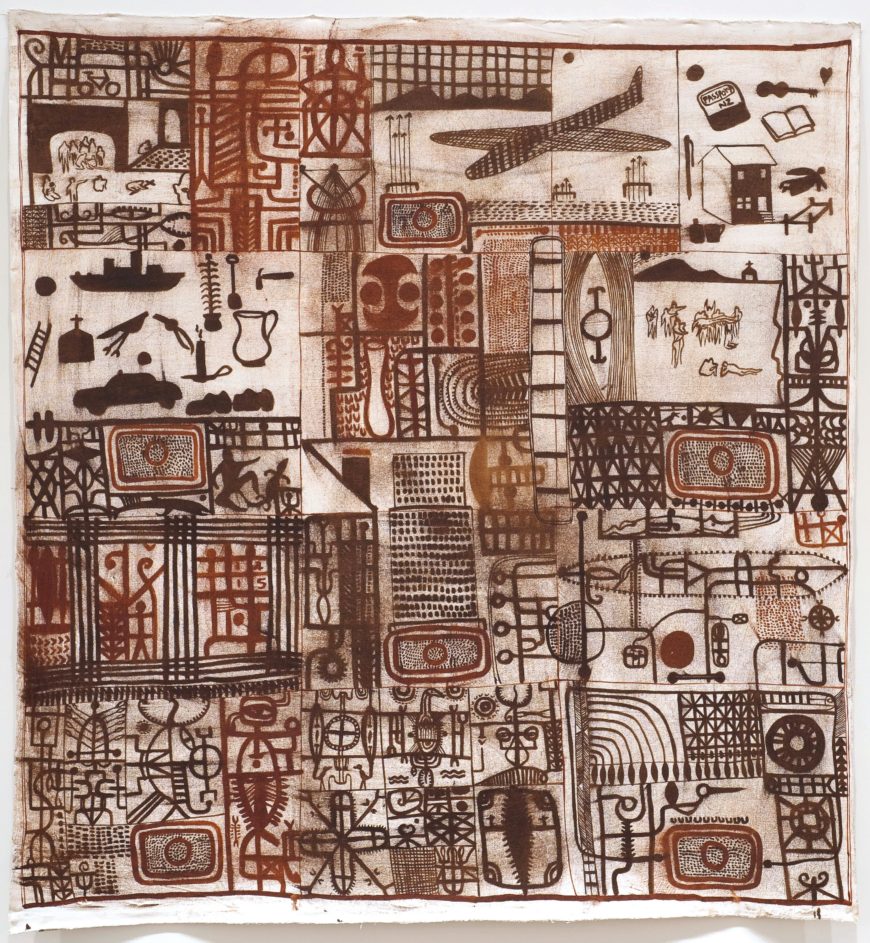

In the 1880s, a distinctive style of hiapo decorations emerged that incorporated fine lines and new motifs. Hiapo from this period are illustrated with complicated and detailed geometric designs. The patterns were composed of spirals, concentric circles, squares, triangles, and diminishing motifs (the design motifs decrease in size from the border to the center of the textile). Niueans created naturalistic motifs and were the first Polynesians to introduce depictions of human figures into their bark cloth. Some hiapo examples include writing, usually names, along the edges of the overall design.

John Pule, Take These With You When You Leave, 1998, oil on canvas, 188 x 185 cm (Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki) © John Pule

Niuean hiapo stopped being produced in the late nineteenth century. Today, the art form has a unique place in history and serves to inspire contemporary Polynesian artists. A well-known example is Niuean artist John Pule, who creates art of mixed media inspired by traditional hiapo design.

Tapa today

Tapa traditions were regionally unique and historically widespread throughout the Polynesian Islands. Eastern Polynesia did not experience a continuous tradition of tapa production, however, the art form is still produced today, particularly in the Hawaiian and the Marquesas Islands. In contrast, Western Polynesia has experienced a continuous tradition of tapa production. Today, bark cloth participates in native patterns of celebration, reciprocity and exchange, as well as in new cultural contexts where it inspires new audiences, artists, and art forms.

Additional resources

Bark cloth from Wallis and Fortuna.

The Hiapo (tapa) from Niue in the Aukland War Memorial Museum.

Tapa of the Pacific from the Auckland Museum.

Work by John Pule on Google Arts & Culture.

Bark cloth on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Adrienne L. Kaeppler, The Pacific Arts of Polynesia and Micronesia (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Roger Neich and Mick Pendergrast, Traditional Tapa: Textiles of the Pacific (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.,1997).

Simon Kooijman, Polynesian Barkcloth (Aylesbury, U.K.: Shire Ethnography, 1988).

John Pule and Nicolas Thomas, Hiapo Past and Present in Niuean Barkcloth (Dunnedin, Aotearoa/New Zealand: University of Otago Press, 2005).

Karen Stevenson, The Frangipani is Dead: Contemporary Pacific Art in New Zealand 1985–2000 (Aotearoa/New Zealand: Wellington, 2008).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Salatasi,”]