Master sailors fashioned these maps from sticks and cowrie shells, registering relationships between land and sea.

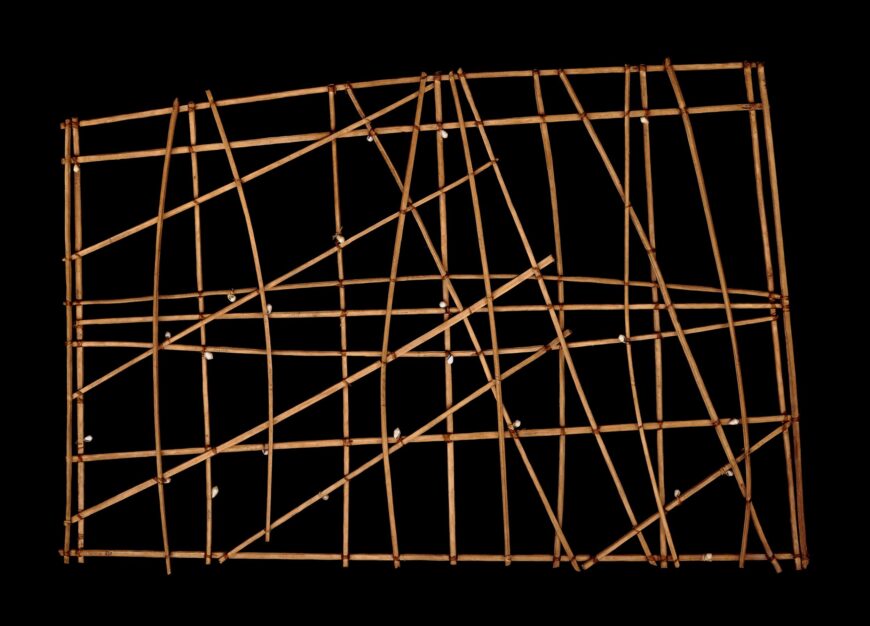

Navigation Chart, late 19th century (Marshall Islands), wood, fiber, and shells (American Museum of Natural History, New York). Speakers: Dr. Jenny Newell, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Tina Stege

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] One of the practices from the Pacific islands that I find most intriguing is mapmaking from the Marshall Islands.

Dr. Jenny Newell: [0:13] The Marshall Islands see themselves as being the greatest navigators in the world. One of the things that you can see as a material representation of this is the wonderful maps. They’re called meddo, or rebbelib. They’re made of sticks and shells, and put together as mental maps of the Marshall Islands and the currents and the swells that link those islands.

Dr. Zucker: [0:34] The maps aren’t used in the way that we use GPS in a car currently, or the way that we used to use a paper map. These aren’t things that the navigators would have taken with them in boats. This is a memory aid.

Dr. Newell: [0:48] It’s a thing that will help you to create a mental map — a good, solid map — so it was only ever used on shore.

Dr. Zucker: [0:50] The Marshall Islands represents an enormous number of islands and atolls in the Pacific. It’s the first major island group that you reach if you’re traveling southwest from Hawaii.

Dr. Newell: [1:01] The Marshall Islands are a set of 29 atolls made up of 1,200, roughly, islands. It takes up a space of about 2 million square kilometers.

Dr. Zucker: [1:13] This is almost all water. It’s interesting that this is a map, not of land, but it’s a map of the relationship between land and sea.

Dr. Newell: [1:19] The sea is very much the element that Marshall Islanders live with all the time. It’s a very intimate part of who they are, and their daily lives and their cosmologies. This ocean links them, it’s the unifying element.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] I think of the ocean as a barrier, but this is the reverse. The ocean is the thing that creates a relationship between the atolls and the islands.

Dr. Newell: [1:38] The great Tongan scholar, Epeli Hau’ofa, has written very eloquently and powerfully about this. That this is our “sea of islands.” The way they’re all connected, they’re connected by the ocean, they’re not separated by it.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] I love that the cowrie shells represent the islands, and they’re really small. Most of the chart is wood, it’s sticks. It beautifully expresses how isolated those islands are, but brought together within this greater matrix of the wood, of the ocean.

Dr. Newell: [2:03] Each one of these charts is different because it’s made by a navigator to represent the way he sees this ocean with its islands, and how to get between them. This one here is one that was collected by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Dr. Zucker: [2:15] The author?

Dr. Newell: [2:16] That’s right. He and his family traveled to the Marshalls. He bought this here, or was given it, and then later on it was sold in his estate.

Dr. Zucker: [2:24] It seems impossible that you could create a map of the open ocean, but the way that these function, in a general sense, is that they’re registering the swells, the currents, the landmarks of the open sea.

Dr. Newell: [2:36] In most of the charts, you’ll see there’s these curving sticks. Those ones are like the echoes of the swells and the waves out from an island. When they hit an island, they then echo back out. Then you can see the longer sticks are the ones which are currents, and there’s also sticks which are like the pathways from one place to another that the navigators wanted to emphasize.

Dr. Zucker: [2:54] It makes sense that the chart is recording the way in which the water is responsive to the islands, since these islands are low and probably can’t be seen until you’re right up against them.

Dr. Newell: [3:09] That’s one of the great skills of Marshallese, and other Micronesian, navigators, is that as soon as you are just a little way beyond your atoll, your island, you can’t see landforms anymore, you have to just be able to read the sea.

Dr. Zucker: [3:21] It’s a reminder of how treacherous the ocean could be for somebody who was not a skilled navigator, and how important passing knowledge from a senior navigator to somebody who’s just learning that craft is.

Dr. Newell: [3:29] The master navigators would take the younger men out on the canoes, and they would have them lie down in the canoe and feel the waves. You can feel when there’s one current intersecting another, and you can feel the way the boat rocks differently.

[3:47] These are very beautifully designed outrigger canoes. They are very highly attuned to their specific lagoon and sea environment and working in all sorts of difficult sailing conditions.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] That relationship with the sea is changing rapidly now.

Dr. Newell: [3:56] The big issue for the Marshall Islanders now is climate change. You know, in the past it’s been nuclear testing.

Dr. Zucker: [4:08] In the 1940s and the 1950s, this was a place where the United States tested its hydrogen bombs, most famously at the Bikini Atoll.

Dr. Newell: [4:11] Marshall Islanders are still living with that legacy. There’s still testing going on, but not of nuclear weapons, it’s more ballistic missiles now.

[4:23] Part of what has come out of that is that there’s this Compact of Free Association between the Marshall Islands and United States, which means that the people from the Republic of the Marshall Islands can live and work in the States.

Dr. Zucker: [4:29] One can only imagine what a contemporary map would look like now, one that spanned not only islands, but nations.

Dr. Newell: [4:37] Certainly these maps are now fulfilling a very different role. They’re much more about navigating identities and connections to place. They are put on people’s walls, so if someone from Majuro, the capital of the Marshalls, moves out to New York, they might take one of these.

[4:59] I’ve been working with Tina Stege from the Marshall Islands for a number of years. She wrote a beautiful piece to talk about climate change. I wanted her to read it out for us.

Tina Stege: [5:00] I called this “We Are Navigating Threatening Seas.” Our ancestors sailed to the Marshall Islands over 1,000 years ago in canoes. It was a feat of wayfinding that sustains and inspires those of us now looking for a way forward in threatening seas.

[5:16] This is also a story of our children, and the generations to come. What will it mean to them to be Marshallese? Will they know the names of their home islands and the wato, the land parcels that bind us to the earth and to each other?

[5:31] Will they think of the ocean as a part of themselves? Will it be a source of sustenance and a vast network of waves, each with names leading like roads to other islands? Will they know the smell of maan, the pandanus fiber we use to weave everything, clothing, mats, baskets, the small flowers we wear in our hair. What will the world be like for them?

[0:00] [music]

Navigation between the islands

The Marshall Islands in eastern Micronesia consist of thirty-four coral atolls consisting of more than one thousand islands and islets spread out across an area of several hundred miles. In order to maintain links between the islands, the Marshall Islanders built seafaring canoes. These vessels were both quick and manouverable. The islanders developed a reputation for navigation between the islands—not a simple matter, since they are all so low that none can be seen from more than a few miles away.

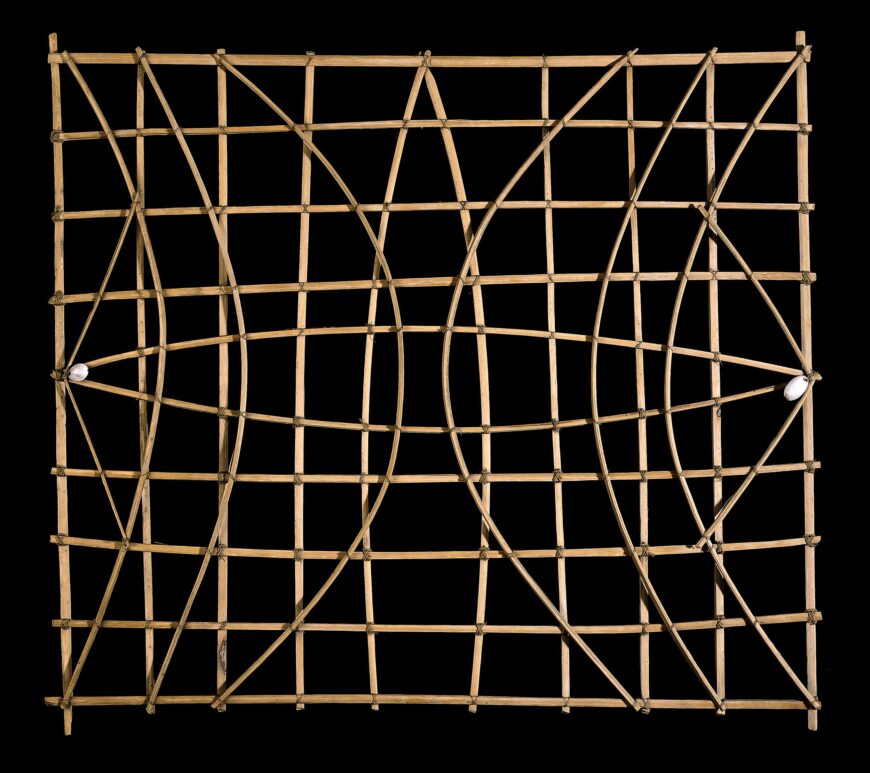

In order to determine a system of piloting and navigation the islanders devised charts that marked not only the locations of the islands, but their knowledge of the swell and wave patterns as well. The charts were composed of wooden sticks; the horizontal and vertical sticks act as supports, while diagonal and curved ones represent wave swells. Cowrie or other small shells represent the position of the islands. The information was memorized and the charts would not be carried on voyages.

Navigation chart (rebbelib), probably 19th century C.E. (Marshall Islands, Micronesia), wood, shell, and fiber, 67.5 x 99 x 3 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Rebbelib

This chart is of a type known as a rebbelib, which cover either a large section or all of the Marshall Islands. Other types of chart more commonly show a smaller area. This example represents the two chains of islands which form the Marshall Islands. It was collected by Admiral E.H.M. Davis during the cruise of HMS Royalist from 1890 to 1893.

Navigation chart (mattang), probably 19th or early 20th century C.E. (Marshall Islands, Micronesia), wood, shell, and fiber, 64 x 58 x 1.7 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Mattang

This chart is of the type known as a mattang, specifically made for the purpose of training people selected to be navigators. Such charts depict general information about swell movements around one or more small islands. Trainees were taught by experienced navigators.

© The Trustees of the British Museum