Oh Lono shake out a net-full of food,

A net-full of rain.

Gather them together for us.

Accumulate food, Oh Lono!

Collect fish, Oh Lono! (Hawaiian prayer to the God Lono)

Many islands

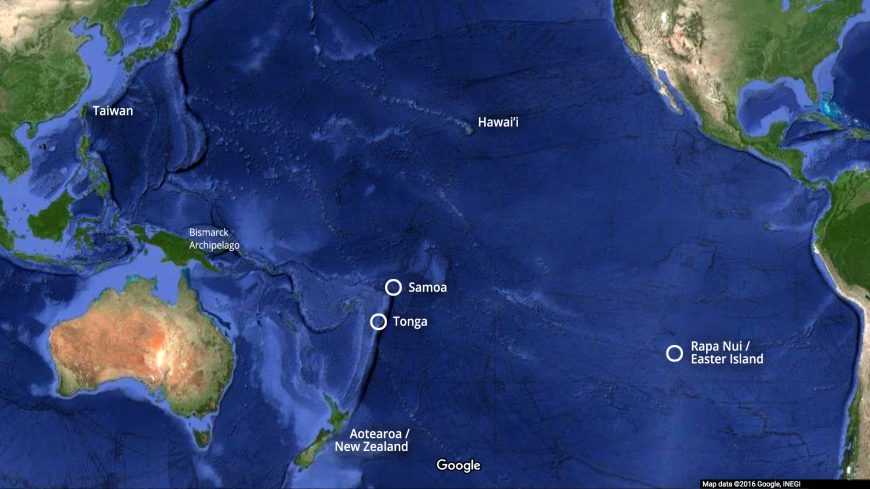

The islands of the eastern Pacific are known as Polynesia, from the Greek for “many islands.” Set within a triangle formed by Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the south, Hawaiʻi to the north and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, the Polynesian islands are dotted across the vast eastern Pacific Ocean. Though small and separated by thousands of miles, they share similar environments and were settled by people with a common cultural heritage. The western Polynesian islands of Fiji and Tonga were settled approximately 3,000 years ago, whilst New Zealand was settled as recently as 1200 C.E.

These people were exceptional boat builders and sailed across the Pacific navigating by currents, stars, and cloud formations. They were skilled fishermen and farmers, growing fruit trees and vegetables and raising pigs, chickens and dogs. Islanders were also accomplished craftspeople and worked in wood, fibre, and feathers to create objects of power and beauty.

They were poets, musicians, dancers, and orators. Eleven closely-linked languages were spoken across the region. They were so similar that Tupaia, a Tahitian who joined Captain Cook on his first voyage, was able to converse with islanders more than two thousand miles away in New Zealand.

Figure of the war god Kūkaʻilimoku, c. 1790–1810, C.E., 272 cm high, Hawaiʻi (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Their societies were hierarchical, with the highest ranking people tracing their descent directly from the gods. These gods were all powerful and present in the world. Images of them were created in wood, feathers, fibre and stone. One of the most important items in the Museum’s collections is a carved wood figure of the Hawaiian god, Kūkaʻilimoku, which stands over two and a half meters tall.

This large and intimidating figure was erected by King Kamehameha I, unifier of the Hawaiian islands at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century. Kamehameha built a number of temples to his god, Kūkaʻilimoku (‘Kū, the snatcher of land’), in the Kona district, Hawaiʻi, seeking the god’s support in his further military ambitions. The figure is likely to have been a subsidiary image in the most sacred part of one of these temples: not so much a representation of the god as a vehicle for the god to enter. Islanders grew fruit trees and used the wood to carve figures. This one depicts Kū, the “land snatcher.” The figure is characteristic of the god Kū, especially by his disrespectful open mouth, but his hair, incorporating stylized pigs’ heads, suggests an additional identification with the god Lono. The pigs’ heads are possibly symbolic of wealth.

Today, Polynesian culture continues to develop and change, partly in response to colonialism. Whilst traditional methods and techniques continue to be employed by skilled carvers and weavers, other artists have achieved international success in new media.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources