Tino aitu figure, late 18th century, wood, 35 x 10.2 x 7 cm, Nukuoro, Caroline Islands, Micronesia (Musée du quai Branly)

At the crossroads of cultures

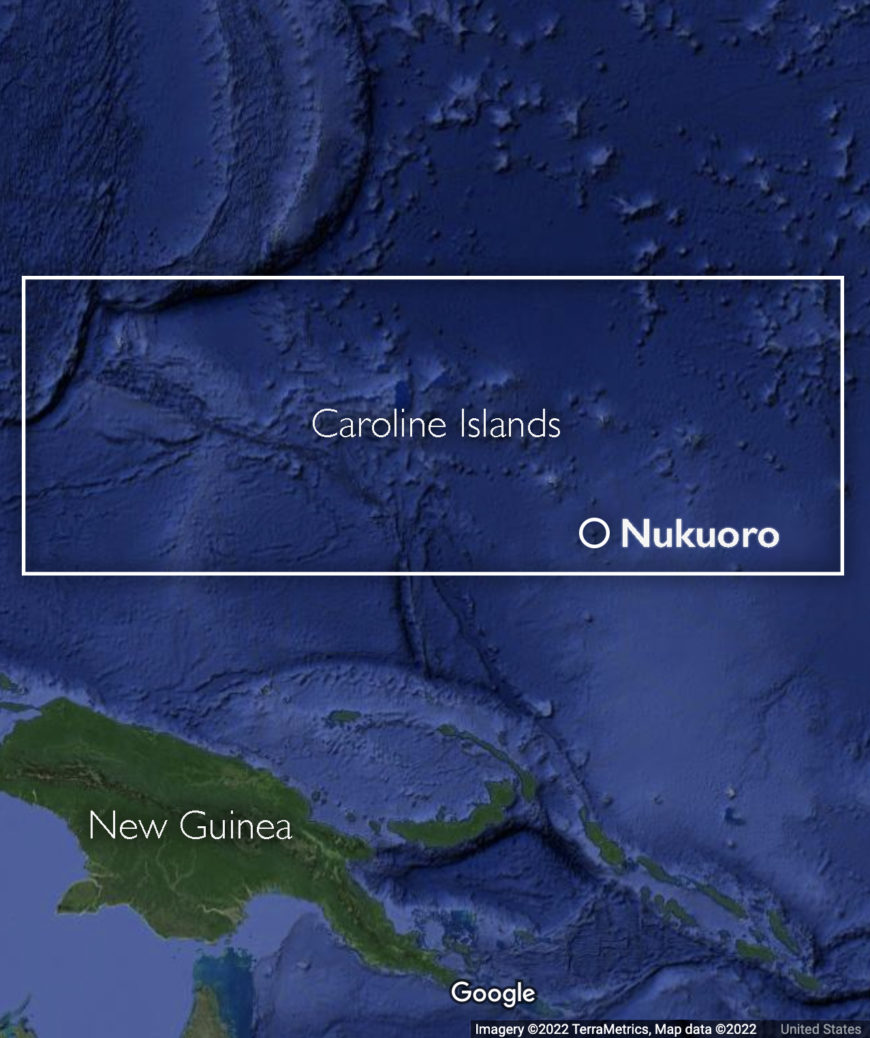

Nukuoro is a small isolated atoll in the archipelago of the Caroline Islands. It is located in Micronesia, a region in the Western Pacific.

Archaeological excavations demonstrate that Nukuoro has been inhabited since at least the eighth century. Oral tradition corroborates these dates relating that people left the Samoan archipelago in two canoes led by their chief Wawe. The canoes first stopped at Nukufetau in Tuvalu and later arrived on the then uninhabited island of Nukuoro. These new Polynesian settlers brought with them ideas of hierarchy and rank, and aesthetic principles such as the carving of stylized human figures. However the new inhabitants also incorporated Micronesian aspects such as the art of navigation, canoe-building and loom-weaving with banana fiber. Because Nukuoro is geographically situated in Micronesia, but is culturally and linguistically essentially Polynesian, it is called a Polynesian Outlier.

Nukuoro Atoll, Micronesia (photo: NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Encounters with Westerners

The Spanish navigator Juan Bautista Monteverde was the first European to sight the atoll on 18 February 1806 when he was on his way from Manila (in the Philippines) to Lima (in South America). The estimated 400 inhabitants of Nukuoro engaged in barter and exchange with Europeans as early as 1830, as can be attested from the presence of Western metal tools. A trading post was only established in 1870. From the 1850s onwards, American Protestant mission teachers who had been posted in the area visited Nukuoro regularly from the Marshall Islands and from the islands Lukunor, Pohnpei, and Kosrae. However, when the American missionary Thomas Gray arrived in Nukuoro in 1902, to baptize a female chief, he found that a large part of the population was already acquainted with Christianity through a Nukuoroan woman who had lived on Pohnpei. When Gray returned three years later, he found that the local sacred ground (marae) and the large temple had been replaced by a church. By 1913, many of the pre-Christian traditions including dances, songs, and stories were lost. Most of the wooden images had been taken off the island before 1885 and subsequently lost their function.

Figure, Nukuoro, Caroline Islands, Micronesia, wood, 54.5 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Earliest sources

In 1874, the missionary Edward T. Doane made the first mention of carved wooden figures. It is unclear, however, where this experienced missionary got his information from as he never left his ship, the Morning Star, to go ashore. Two German men, Johann Stanislaus Kubary, who visited the island in 1873 and in 1877 while working for the Godeffroy trading company and its museum, and Carl Jeschke, a ship’s captain who first visited the atoll in 1904 and then regularly between 1910 and 1913, give the most detailed information on the Nukuoroan figures.

Tino aitu figure, before 1830, Nukuoro, Caroline Islands, Micronesia, wood (Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg; photo: Paul Schimweg)

Wooden sculptures

The first Europeans to collect the Nukuoro sculptures found them coarse and clumsy. It is not known whether the breadfruit tree (Artocarpus altilis) images were carved with local adzes equipped with Tridacna shell blades or with Western metal blade tools. The surfaces were smoothed with pumice which was abundantly available on the beach. All the sculptures, ranging in size from 30 cm to 217 cm, have similar proportions: an ovoid head tapering slightly at the chin and a columnar neck. The eyes and nose are either discretely shown as slits or not at all. The shoulders slope downwards and the chest is indicated by a simple line. Some female figures have rudimentary breasts. Some of the sculptures, be they male, female or of indeterminate sex, have a sketchy indication of hands and feet. The buttocks are always flattened and set on a flexed pair of legs.

Deities

Local deities in Nukuoro resided in animals or were represented in stones, pieces of wood, or wooden figurines (tino aitu). Each of the figurines bore the name of a specific male or female deity which was associated with a particular extended family group, a priest and a specific temple. They were placed in temples and decorated with loom-woven bands, fine mats, feathers, paint, or headdresses. The tino aitu occupied a central place in an important religious ceremony that took place towards the month of Mataariki, when the Pleiades are visible in the west at dusk. The rituals marked the beginning of the harvesting of two kinds of taro, breadfruit, arrowroot, banana, sugar cane, pandanus, and coconuts. During the festivities—which could last several weeks—the harvested fruits and food offerings were brought to the wooden sculptures, male and female dances were performed and women were tattooed. Any weathered and rotten statues were also replaced during the ceremony. For the period of these rituals, the sculptures were considered the resting place of a god or a deified ancestor’s spirit.

Early twentieth-century artists

Alberto Giacometti, Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object), 1934 (cast c. 1954–55), bronze, 152.1 x 32.6 x 25.3 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

When the Swiss sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti made his famous sculpture Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object), he was inspired by a wooden Nukuoro figure he had seen at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris (now in the collection of the Musée du quai Branly). A fellow artist, Henry Moore, considered the Nukuoro image at the British Museum to be one of the highlights in the history of sculpture. Both carvings are part of a small group of thirty-seven sculptures from Nukuoro that arrived in Western museum collections from the 1870s onwards. European artists believed that the highly stylized representation of the human in the Nukuoro figures represented the purest form of art—an art that lay at the origins of mankind.

Nukuoro figures today

Today the sight of even a small Nukuoro figure still makes a big impact on visitors. Scattered across museums and private collections in Europe, North America, and New Zealand, ten figures were brought together for the first time at the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, near the Swiss city of Basel. This prompted research in these exquisite sculptures, which has been bundled in a book Nukuoro: Sculptures from Micronesia (2013). Nukuoro figures continue to inspire Nukuoroans and Westerners alike as they are copied, and displayed in places ranging from people’s houses to Pacific themed hotel lobbies.

Additional resources

Nukuoro figure in the George Ortiz Collection.

Roger Neich, “A Recently Revealed Tino Aitu Figure from Nukuoro Island, Caroline Islands, Micronesia” (Aukland Museum and University of Aukland, 2008).

Christina Hellmich, “A tino aitu figure below the surface” in Nukuoro: Sculptures from Micronesia, ed. C. Kaufmann and O. Wick (2014).

Animation from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration about how atolls are formed.

Adrienne L. Kaeppler, The Pacific Arts of Polynesia & Micronesia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Christian Kaufmann, & Oliver Wick (eds), Nukuoro. Sculptures from Micronesia (Basel: Fondation Beyeler, Hirmer, 2013).