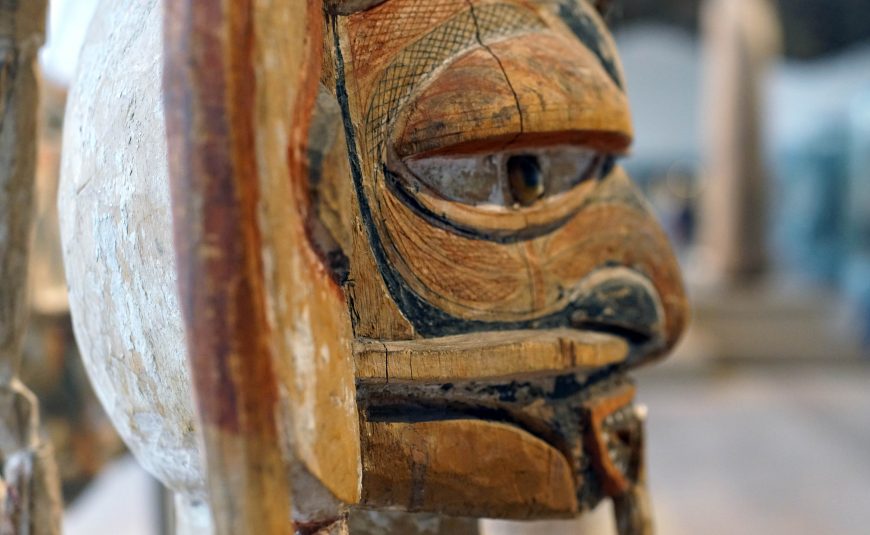

Funerary Carving (Malagan), late 19th–early 20th century, New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, wood, 280.7 x 87.6 x 26.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Tatanua, c. late 19th century, New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, wood, pith, and shell, 49.5 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Let us assume this: that there is life in everything, and that living continues long after death. Certainly, we humans are alive; as are dogs, cats, lizards, fish, trees, and birds. But so too are rivers, forests, stones, boats, buildings, and even computers. All these lives and many more have one quality in common: they are relational beings. By that I mean they have the ability to interact with other living things and affect other lives in some way. Beyond anything else, it is through this ability to build relationships that we all remain alive in one form or another. From this basic premise, we can begin to understand the lives of malagan.

What are malagan?

The term malagan (also spelled malangan or malanggan) usually refers to one or more intricate carvings from the island of New Ireland in Papua New Guinea. These carvings may take the form of a mask, a wooden board or “frieze,” a sturdy housepole, a circular, woven mat, or a scaled model of a dugout canoe with or without human figures inside. In many such forms, malagan can be found in museums throughout the world. All of these well-traveled carvings were born in New Ireland, a place of extraordinary diversity. There alone, over thirty distinct languages are spoken. In most of these languages, the word malagan means “likeness,” or otherwise “to carve, or inscribe.”

To see a malagan in person or in a photograph is to meet many inscribed likenesses or motifs, each entwined to form a single, visible organism. Of these, there are several species: on mask-like malagan (referred to as Lentanon or Tantanua), we normally see a contrast in color and texture in hemispheric shapes above the face. Another, the Walik malagan, typically features two birds or two fish poised on opposite sides of the same hole, or “eye.” The Wowara malagan are characterized by a circular “sun” motif, and are typically woven from smooth, flat palm fronds. Upon seeing a malagan with its various motifs, we might ask, what does it mean? Or otherwise, considering the careful detail that goes into them, we might question the tools and techniques utilized by master carvers in their production.

What do malagan do?

Wowara (the radial shapes) and a Walik in between (the two lobsters) displayed at the annual “New Ireland Day” festival, 2016 (photo: Elisha Omar)

With such variation emerging from so many common motifs, malagan have confused and confounded anthropologists and art historians for over a century. Only recently have scholars begun to think differently about them. Rather than asking what each motif means, we are now listening more closely to the people of New Ireland and asking what each assemblage of motifs does in the world. By understanding these composite forms as agents, we can begin to see how malagan inspire, nurture, and participate in social life. To see this agency in action requires we look closely at the socioecological context out of which malagan come to life.

New Ireland

New Ireland is a narrow, tropical island only a few degrees south of the Equator. There are two primary seasons: a hot and dry period lasting from March to around November, and a rainy monsoon in December, January, and February. There are two modest towns on the island, but the majority of people live in rural villages. These Indigenous residents spend the majority of their time in their beautiful gardens, where they grow sweet potatoes, cassava, bananas, various greens, and taro. In the village, they raise pigs, feeding them the white meat of dried coconuts. A significant part of their diet comes from the sea. They catch smaller fish on the coral reefs and larger fish like tuna and snapper in the deep ocean. While the fish can be caught year-round, the majority of garden food is harvested after the monsoon. Assuming the gardens are maintained properly (with labor as well as a kind of fertility magic), this seasonal variability yields a surplus of crops—far more than required for basic sustenance. This is fortunate, for the arrival of the dry season marks the time when large, elaborate feasts are held throughout the island to foster the passage of recently departed relatives into the afterlife.

Pig (detail), Funerary Carving (Malagan), late 19th–early 20th century, Papua New Guinea, New Ireland, New Ireland, wood, 280.7 x 87.6 x 26.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mortuary feasts

The people of New Ireland take these mortuary rituals very seriously. Throughout the year, as the crops grow larger and pigs grow fatter, the feasts are planned by the families of the deceased. Only when all the materials are ready—when enough pigs have been marked for sacrifice, enough taro has been dug out of the garden, and enough traditional shell-money (or mis) has been amassed—will the host family announce the impending event to the entire island. Malagan is the name given to these large mortuary feasts, but it more accurately refers to the carvings that are revealed with great flourish and excitement in the final moments of the event. At that time, hundreds or even thousands of people have gathered to witness a process of customary work led by an appointed cultural leader, or maimai. Dressed conspicuously in red, the maimai coordinates the entire event. He says when the pigs should be killed, when the taro should be peeled and roasted, and when various singsing groups should perform their unique song and dance. He supervises and coordinates obligatory exchange of mis (a traditional form of currency) and paper money between the family of the deceased and others who have supported them in their grief.

Felix Speiser, Group of malagan carvings displayed during a mortuary ceremony, Medina, Northern New Ireland, c. 1930 (Museum der Kulturen Basel)

With bold chants and avian gestures, the maimai gathers everyone together for the grand revelation of one or more malagan carvings. It is his responsibility to ensure everyone witnesses the powerful malagan, pays for the experience of seeing it, and then consumes all of the prepared food before returning to their homes at sundown. This dramatic revelation brings the living malagan into the social world, but only for a brief moment. For many months prior to the final event, a skilled carver secludes himself in a special enclosure, well out of sight from those in the village. With seashells, stones, knives, sharks’ teeth, fire, and natural pigments, he inscribes into a piece of monsoon-borne driftwood a set of images that have come to him in a dream. Snakes, crocodiles, birds, fish, and other motifs are brought into relief, many of which hold a special association with a particular matriline. [1] Through the sweat and fire of his efforts, a powerful assemblage comes to life.

Fish (detail), Funerary Carving (Malagan), late 19th–early 20th century, Papua New Guinea, New Ireland, New Ireland, wood, 280.7 x 87.6 x 26.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When it is finally revealed to the public, the malagan is considered “hot” and dangerous. Only when its witnesses “buy” it with mis, and when the feasting is complete, does its power diminish. The once-powerful malagan is cast aside to decay in the tropical forest, or is otherwise sold off to foreign tourists or museums. This final dismissal marks the “finishing” of the dead, when all the work of mourning and customary obligations has been settled. The dead are “sent away to biksolwara”—to the deep sea where everything has come from and to where everything eventually returns.

Profile (detail), Funerary Carving (Malagan), late 19th–early 20th century, Northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, wood, paint, shell, resin, 132.7 x 34.9 x 33.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The power of the malagan

Like the maimai, the power or vitality of the malagan lies in its capacity to bring multiple clans together so that they may see each other, see themselves, and witness what the master carver has brought to life. Long after a dead receive their final malagan feast, part of that person remains active in the social world in the form of memory. Suppose, for example, a woman is working in the garden and sees a londoli (frigatebird) soaring overhead. There, for a brief moment, the graceful form of the bird prompts her to recall the intricate detail of malagan carved for her old uncle, who died when she was only a child. That uncle, who long ago was sent away over the sea, enters back into her world through the power of that one, particularly memorable motif. In this capacity, malagan and their associated mortuary rites ensure a vibrant social life for the people of New Ireland, and an eternal afterlife for their ancestors.

Notes:

[1] Common throughout the Papua New Guinea islands, matriline refers to a descent group in which membership is inherited from one’s mother.

Additional resources

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

New Ireland on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Papua New Guinea at the Penn Museum