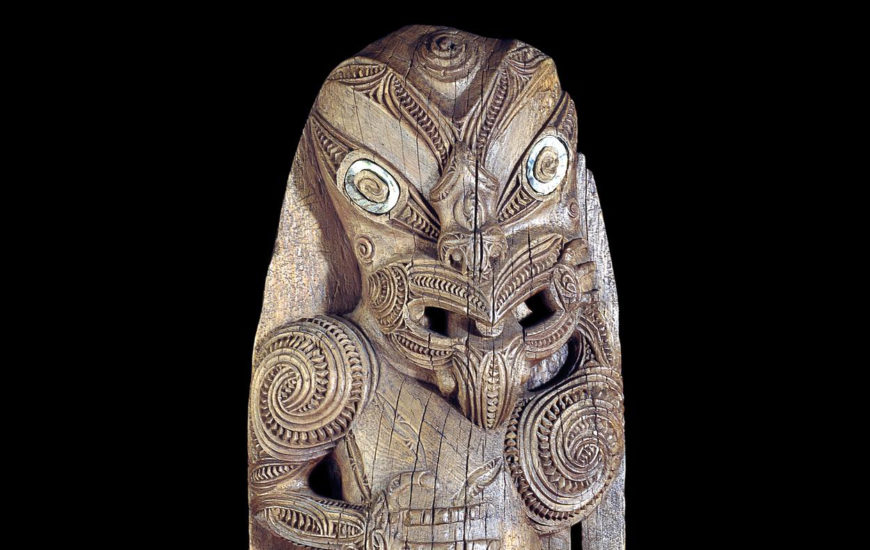

Upper figure (detail), House-board (amo), 1830–60 (Māori, Poverty Bay district, New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 152 x 43 x 15 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Marae

The Māori built meeting houses before the period of contact with Europeans. The early structures appear to have been used as the homes of chiefs, though they were also used for accommodating guests. They did not exist in every community. From the middle of the nineteenth century, however, they started to develop into an important focal point of local society. Larger meeting houses were built, and they ceased to be used as homes. The open space in front of the house, known as a marae, is used as an assembly ground. They were, and still are, used for entertaining, for funerals, religious, and political meetings. It is a focus of tribal pride and is treated with great respect.

Front of a Māori community meeting house with carved end posts on either side of the veranda, maihi (carved barge-boards), raparapa (projecting boards at the end of the maihi), tekoteko (figurative carving at the front of the apex of the roof), koruru (carved mask depicting the ancestor the house is named for, placed below thetekoteko), and pare (carved lintel above doorway window). Josiah Martin, Exterior of a Māori marae (community meeting house), Hinemihi, in the village of Te Wairoa, 1881, albumen print, 15.3 x 20.5 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Pare

The meeting house is regarded as sacred. Some areas are held as more sacred than others, especially the front of the house. The lintel (pare) above the doorway is considered the most important carving, marking the passage from the domain of one god to that of another. Outside the meeting house is often referred to as the domain of Tumatauenga, the god of war, and thus of hostility and conflict. The calm and peaceful interior is the domain of Rongo, the god of agriculture and other peaceful pursuits.

Three wheku figures with haliotis shell eyes, raised arms, surface decoration of spirals and pakura, separated and flanked by takarangi spirals. Solid base with bands of rauponga, central rauponga spiral and two terminal manaia with haliotis-shell eyes under feet of outer wheku figures. Wooden openwork lintel (pare), c. late 1840s (Bay of Plenty, North Island, New Zealand), wood stained black, haliotis shells, 131.5 x 43.5 x 5.5 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The example above illustrates one of the two main forms of door lintel. The three figures, with eyes inlaid with rings of haliotis shell, are standing on a base which symbolizes Papa or Earth. The scene refers to the moment of the creation of the world as the three figures push the sky god Rangi and earth apart. The three figures are Rangi and Papa’s children, the central one probably representing Tane, god of the forests. The two large spirals represent light and knowledge entering the world. The lintel was probably carved in the Whakatane district of the Bay of Plenty in the late 1840s.

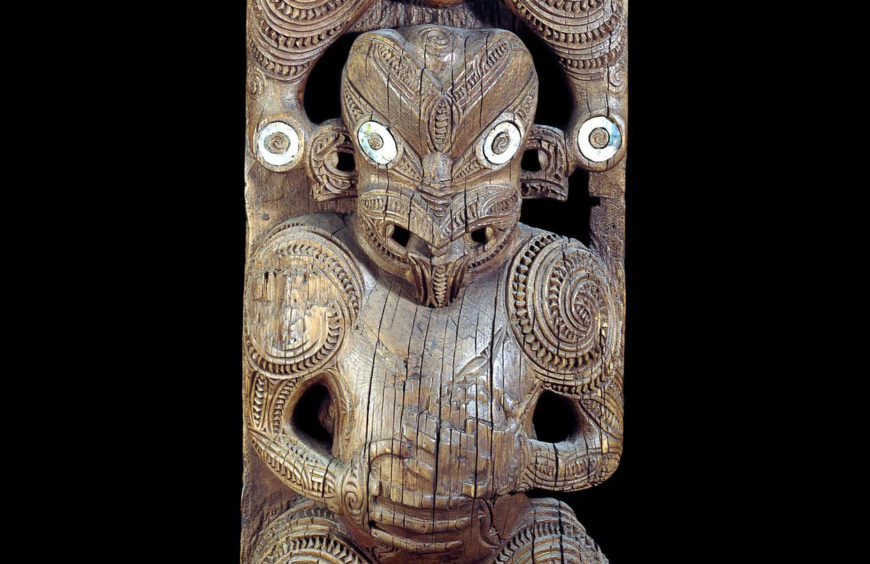

House-board (amo), 1830–60 (Māori, Poverty Bay district, New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 152 x 43 x 15 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Amo

This is a side post or amo from the front of a meeting house. A pair of amo would have supported the sloping barge boards of the house. The two carved figures represent named ancestors of the tribal group who owned the meeting house. The figures are male, but the phalluses have been removed, probably after they were collected. Their eyes are inlaid with rings of haliotis shell. They are carved in relief with rauponga patterns, a style of Māori carved decoration in which a notched ridge is bordered by parallel plain ridges and grooves. Roger Neich, an expert on the subject of Māori carving, has identified the style of the carving of the post as that of the district of Poverty Bay in the East Coast area of the North Island.

Lower figure (detail), House-board (amo), 1830–60 (Māori, Poverty Bay district, New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 152 x 43 x 15 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

This is one of a group of seven carvings purchased from Lady Sudeley in 1894. They were collected in New Zealand by her uncle, the Hon. Algernon Tollemache, probably between 1850 and 1873. This board and another from the same collection form a pair.

![Māori male hair topknot and a fully tattooed face (detail), Carved male figure (from the base of a poutokomanawa), mid-19th century (Māori, Hawkes Bay [?], New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 85 x 26 x 18 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/34035001_d-870x571.jpg)

Māori male hair topknot and a fully tattooed face (detail), Carved male figure (from the base of a poutokomanawa), mid-19th century (Māori, Hawkes Bay [?], New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 85 x 26 x 18 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

![Carved male figure (from the base of apoutokomanawa), mid-19th century (Māori, Hawkes Bay [?], New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 85 x 26 x 18 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/34035001_d-1-300x696.jpg)

Carved male figure (from the base of apoutokomanawa), mid-19th century (Māori, Hawkes Bay [?], New Zealand), wood, haliotis shell, 85 x 26 x 18 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Poutokomanawa figure

This male figure is from the base of a poutokomanawa, an internal central post which supports the ridge-pole of a Maori meeting house. It represents an important ancestor of the tribal group which owned that house. The figure has fairly naturalistic features. It is clearly male, and has the typical Māori male hair topknot and a fully tattooed face. The eyes are inlaid with haliotis shell. The collar bone is carved as a raised ridge. The large hands have just three fingers each. This is not unusual, varying numbers of fingers are to be found on Maori carvings, and may be due to regional differences in style, rather than having a symbolic meaning.

The style of carving—the solidly proportioned body and large hands—is typical of the prominent Ngati Kahungunu school of carvers from the central Hawkes Bay district, in the mid-nineteenth century. The majority of Māori carving from this period is more stylized than this figure. This naturalistic style may have been intended to emphasize the social or human side of the ancestor represented.

The Māori meeting house increased in size and height during the nineteenth century, due partly to European influence. Consequently, poutokomanawa figures increased in size until the largest were around two meters high.

© The Trustees of the British Museum