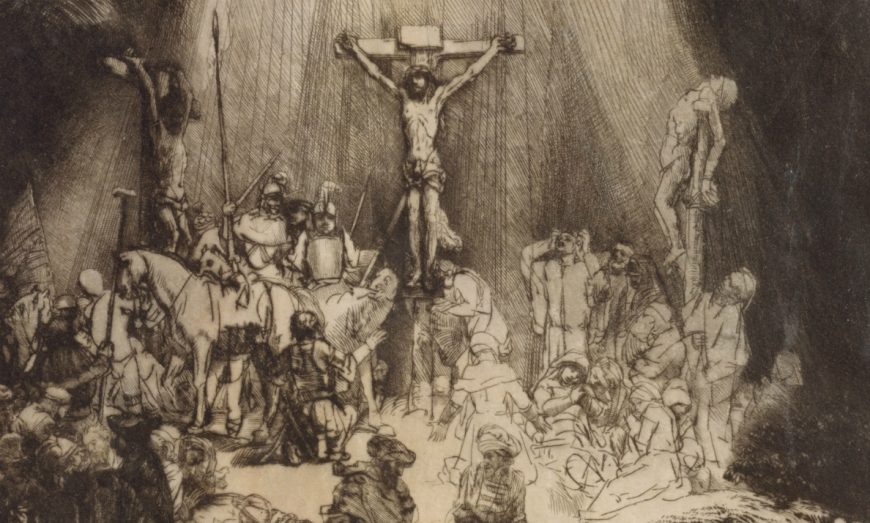

Though based on of a painting, it’s clear that Rubens saw this print as an independent work of art.

Heyndrik Withouck after Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, 1638, engraving and etching, 61.5 x 124.5 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Speakers: Benjamin Weiss, Leonard A. Lauder Senior Curator of Visual Culture, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Beth Harris

VISITFLANDERS has joined forces with Smarthistory and the Center for Netherlandish Art at the MFA Boston to bring you a series of video conversations with curators on important Flemish paintings by artists such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, Peter Paul Rubens, and James Ensor.