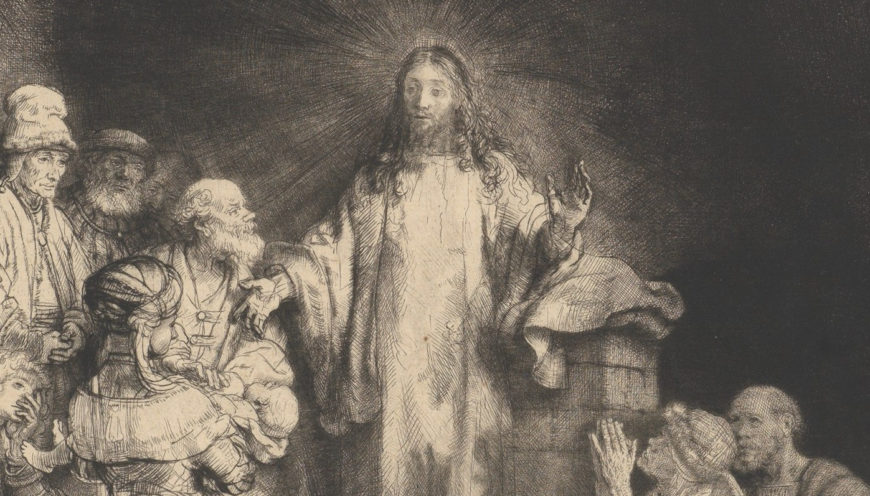

Rembrandt, The Hundred Guilder Print, c. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint; second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

It cost how much?!

What is art worth? A painting depicting the Salvator Mundi (Christ as savior of the world), often attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, sold for 450.3 million dollars in 2017. Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God had an asking price of 50 million British pounds in 2007. Things may not have been that different in the seventeenth century. One of Rembrandt’s most technically ambitious prints has been primarily known more for its price tag than for its subject: The Hundred Guilder Print. In her 2021 monograph on the print, art historian Amy Golahny revealed that it was already referred to by this nickname in 1648/49 and singled out by contemporaries for its excellence. A guilder was a unit of currency, and 100 guilders was an enormous amount of money to pay for a print. Most prints were under one guilder, with only very fancy and desirable images getting into double digits. As soon as the print was made, it shot into the stratosphere of value with Rembrandt himself insisting on his own high value.

The Hundred Guilder Print represents a series of moments in the life and ministry of Jesus, drawn from the Bible. More than that, however, it presents a perfect opportunity to examine a range of topics within the visual culture of the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic. Not only does it help us understand the economics surrounding printmaking, but it also allows for insight into how the artist manipulated the medium, selected and combined scenes from the Bible within the composition, responded to artistic precedent set by earlier generations of printmakers, and benefitted from the global trade networks that shaped daily life at the time. We can also connect the print to discussions in current museum practice about which stories about the past get told and the role of the museum in creating conversations about diverse populations in both the past and present. The value of the print is not only monetary, but also intellectual, spiritual, and artistic.

Printmaking: use and value in the seventeenth century

Although you may be more familiar with Rembrandt as a painter, he was also one of the most skilled and ambitious printmakers of the seventeenth century. He probably began making prints in the 1620s. Scholars don’t know exactly what prompted him to adopt the medium, but it was a useful skill set for any aspiring artist. Earlier Northern Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer, who had worked in both painted and printed media, had helped elevate the prestige attached to printmaking.

By Rembrandt’s time, prints were more than merely illustrations of biblical or popular texts and functioned as an independent art form of their own. They were avidly collected and Rembrandt himself amassed a sizable print collection that included many works by artists from across Europe. Prints advertised the compositions of an artist and could spread farther, faster, and more economically than painted images. In addition, Rembrandt, like other artists, used prints as inspiration, working and reworking motifs to emulate previous generations of printmakers thereby demonstrating his own ingenuity. Numerous scholars of Dutch art have written detailed discussions of how Rembrandt has borrowed motifs from Leonardo, Raphael, and Martin Schongauer in the Hundred Guilder Print. However, rather than merely copying a pose, Rembrandt creatively reinvented his sources.

As an artist who could perhaps be understood as a brand-conscious influencer, Rembrandt usually filled his painted and printed works with his face and his signature. But he did not sign the Hundred Guilder Print. It is its own signature: at the time, no one else could possibly have created a printed image like this because of the technical complexity and manual skill required. Rembrandt innovatively combined multiple different techniques on the copper plate as well as making unusual decisions about the paper and ink used.

Two techniques: etching and drypoint

The image combines two different techniques: etching and drypoint. Etching is a chemical process. A printmaker would treat the surface of a copper plate with a resist—a waxy substance used to cover and protect the plate. Marks are then made in the resist, revealing the copper beneath and exposing it so that when the metal is placed in a chemical solution, acids will eat away at the revealed copper. This creates grooves and depressions in the surface that can then be inked and printed.

By contrast, in drypoint a printmaker cuts directly into the plate itself, creating the reservoir for ink. The copper is not cut away with the drypoint process, but rather pushed to the side, creating a burr of copper above the surface of the sheet that “grabs onto” more ink and creates a deep, rich, often fuzzy line. By combining techniques, Rembrandt makes use of the widest possible range of marks to create highly detailed, heavily worked sections that dissolve into inky darkness as well as more cursorily worked areas that might draw our eye less.

The print exists in two states, or versions. Every time a printmaker reworks a plate and reprints the same image with some changes, a new “state” is created. To really understand a print by Rembrandt and to follow his design process it is often necessary to examine many different impressions of the same print. In addition to changes to the copper plate itself, he also experimented with ink application and paper type.

Left: printed on Japanese paper (Rijksmuseum); right: printed on European (white) paper (National Gallery of Art)

Some impressions were printed on a paper imported from Japan. Because it is made from different materials, the paper absorbs and supports the ink differently than local European paper. Although the changes between the states of the Hundred Guilder Print are quite small, the ink and paper choice makes a significant difference in appearance, as the lush plate tone created on the Japanese paper gives a warmth and softness that the European paper lacks. The differences are even more pronounced when viewed in person.

The subject and composition

Jesus stands just to the left of the center with his right hand gesturing slightly downwards and his left held up as if in a gesture of blessing. He stands out against the inky darkness behind him due to the modulation of light and dark. Rembrandt’s handling of the plate here creates the sense that Jesus is emanating a holy light. Even his hands are outlined so that they stand out against the background.

Christ (detail), Rembrandt, The Hundred Guilder Print, c. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint; second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Jesus angles his head to face the woman with the infant while his torso and other arm gesture to the masses in search of healing and instruction. He is surrounded by a throng of figures. Those in closer proximity and off to our right are observed in great detail: figures in complicated headgear, a sick woman at Jesus’s feet, figures kneeling in supplication or being brought in on wheelbarrows fill the right half.

Detail of the right side, Rembrandt, The Hundred Guilder Print, c. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint; second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The figures on the left side of the print are shown in much less detail; Rembrandt has merely sketched in outlines and general forms of men both standing and seated. The complex grouping of bodies seems to occupy a single plane within the composition, like a frieze. Jesus stands on a slight rise and in front of a wall of some sort, while the figures to the right seem to be coming through an arch. The space behind the figures is ambiguous: it is unclear where this group has assembled, and whether we are seeing a stony outcrop, a manmade structure, or some sort of ruin behind them. This focuses our attention on the events unfolding and prevents us from wandering off into a distant landscape.

Detail of the left side, Rembrandt, The Hundred Guilder Print, c. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint; second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rather than depicting one specific moment from the Bible, such as the Crucifixion or Last Supper, Rembrandt created a composite of several different vignettes. Scholars tend to agree that Rembrandt depicted many different verses from chapter 19 in the Book of Matthew. These include Jesus healing the sick, disagreeing with the Pharisees, telling a rich man to sell his possessions to achieve salvation, and admonishing his disciples to “suffer the children” to come to him. Unlike the most common scenes in art of the life of Jesus, this is not about his birth or death, but about his ministry as teacher and healer. The figure with whom Jesus most directly engages is a mother carrying a baby, presumably a child she is presenting for his care. Selecting multiple verses from the Bible to be simultaneously represented both underscores the richness of Christian ministry while also contrasting the disciples and the doubters.

The divide between the faithful and the skeptical is underscored by the visual choices made by the artist. In contrast to the darker, carefully worked right half of the print containing the faithful and their supplication, the left third of the print is occupied by a group of more sketchily worked figures, including the Pharisees with whom Jesus argues, a man with a staff and fancy hat who anchors the left foreground, and a young well-dressed man with his face in his hands—perhaps the rich man who will be unable to enter the kingdom of heaven because of his earthly goods. Notice how carefully Rembrandt depicted the fancy hat to help balance out the visual weight of the right half of the print.

Rembrandt, the Christian message, and the Globe

It is important to remember that the material and financial wealth of the Dutch Republic was largely derived from global trade. Amsterdam was a trade hub, with people, objects, and ideas coming and going all the time. Though it’s tempting to zoom in on Rembrandt’s masterful line work and his creative narrative and artistic choices, or to theorize about how this image might connect to the artist’s personal religious beliefs, the Hundred Guilder Print also reflects the global context of its creation. It is evidence of how images, ideas, and materials circulated in both artistic and economic markets. Even the Japanese paper speaks to the globally oriented milieu in which Rembrandt lived and worked.

Black figure (detail), Rembrandt, The Hundred Guilder Print, c. 1649, etching, engraving, and drypoint; second state of two, 28 x 39.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Rembrandt included a dark-skinned, perhaps African man in the front right section of the throng surrounding Jesus. He wears an elaborate earring, a common motif for Black figures in art at the time. One way of interpreting his presence—as well as that of the camel—is to see him as evidence that the Christian message was applicable to the whole world. It was common in Renaissance art to depict one of the three wise men (Balthazar) who visited the infant Jesus as African, for example.

The inclusion of a Black figure in Rembrandt’s print is also a technical flex: modeling the light fall on a range of skin tones is a challenge for a printmaker. Rembrandt’s mastery of the medium is evident here. Like many of his contemporaries, Rembrandt often incorporated Black figures into his work, but this has only recently become a topic of discussion for art historians. The economic prosperity that fueled the so-called “Golden Age” of Dutch art was built on global trade networks, many of which depended on either enslaved or exploited populations in Dutch colonies in western and southern Africa, the Caribbean, Brazil, and across the Indian Ocean. While slavery was illegal in The Netherlands at the time, it was quite common in Dutch territorial holdings.

The 2020 exhibition at the Rembrandthuis Museum Black in Rembrandt’s Time added an important layer to our understanding of what life in 17th-century Amsterdam was like for people of color. Some people had been brought to Amsterdam as part of the households of those relocating from places where enslavement was more common or were purchased to serve at court. Other people of color came to the city or passed through it via global networks, perhaps as sailors in navies or merchant ships, in the entourage of diplomats, or as merchants and diplomats themselves. Many of the free Black and African people living in Amsterdam were clustered in Rembrandt’s neighborhood. In his recent research in the Amsterdam archives, historian Mark Ponte has not only discovered evidence of a thriving Black community of at least several dozen individuals during the seventeenth century, but has been able to establish names, occupations, and marriage and baptism dates for them.

The Black man in the Hundred Guilder Print may stand as evidence of Rembrandt’s artistic practice: he worked “naer het leven”—or from life, using live models of all different types. He is even rumored to have pulled his neighbors off the street to model for him! While we cannot link the Black figure in the Hundred Guilder Print to any specific individual, his presence in the print amidst the other faithful followers of Jesus can be a reminder of the complexity of life in Amsterdam at the time. Together with the use of Japanese paper and the pan-European artistic sources, the print speaks to the wider world in both material and spiritual ways.