The end of the world

Y2K. The Rapture. 2012. For over a decade, speculation about the end of the world has run rampant—all in conjunction with the arrival of the new millennium. The same was true for our religious European counterparts who, prior to the year 1000, believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, and the end was nigh.

When the apocalypse failed to materialize in 1000, it was decided that the correct year must be 1033, a thousand years from the death of Jesus Christ, but then that year also passed without any cataclysmic event.

Just how extreme the millennial panic was remains debated. It is certain that from the year 950 onwards, there was a significant increase in building activity, particularly of religious structures. There were many reasons for this construction boom beside millennial panic, and the building of monumental religious structures continued even as fears of the immediate end of time faded.

Not surprisingly, this period also witnessed a surge in the popularity of the religious pilgrimage. A pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place. These are acts of piety and may have been undertaken in gratitude for the fact that doomsday had not arrived, and to ensure salvation, whenever the end did come.

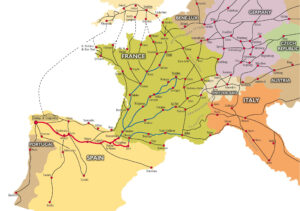

Map of pilgrimage routes (image: Manfred Zentgraf, Volkach, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Pilgrims from the tympanum of Cathedral of Saint Lazare, Autun (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

For the average European in the 12th century, a pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Jerusalem was out of the question—travel to West Asia was too far, too dangerous, and too expensive. Santiago de Compostela in Spain offered a much more convenient option.

To this day, hundreds of thousands of faithful travel the “Way of Saint James” to the Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. They go on foot across Europe to a holy shrine where bones, believed to belong to Saint James, were unearthed. The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela now stands on this site.

The pious of the Middle Ages wanted to pay homage to holy relics, and pilgrimage churches sprang up along the route to Spain. Pilgrims commonly walked barefoot and wore a scalloped shell, the symbol of Saint James (the shell’s grooves symbolize the many roads of the pilgrimage).

In France alone, there were four main routes toward Spain. Le Puy, Arles, Paris, and Vézelay are the cities on these roads, and each contains a church that was an important pilgrimage site in its own right.

Reliquary of Saint Foy at Conque Abbey (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Why make a pilgrimage?

A pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela was an expression of Christian devotion, and it was believed that it could purify the soul and perhaps even produce miraculous healing benefits. A criminal could travel the “Way of Saint James” as an act of penance. For the everyday person, a pilgrimage was also one of the only opportunities to travel and see some of the world. It was a chance to meet people, perhaps even those outside one’s own class. The purpose of pilgrimage may not have been entirely devotional.

The cult of the relic

Pilgrimage churches can be seen in part as popular destinations, a spiritual tourism of sorts for medieval travelers. Guidebooks, badges, and various souvenirs were sold. Pilgrims, though traveling light, would spend money in the towns that possessed important sacred relics.

The cult of relic was at its peak during the Romanesque period, from about 1000–1200. Relics are religious objects generally connected to a saint, or some other venerated person. A relic might be a body part, a saint’s finger, a cloth worn by the Virgin Mary, or a piece of the True Cross.

Relics are often housed in a protective container called a reliquary. Reliquarys are often quite opulent and can be encrusted with precious metals and gemstones given by the faithful. An example is the Reliquary of Saint Foy, located at Conques abbey on the pilgrimage route. It is said to hold a piece of the child martyr’s skull. A large pilgrimage church might be home to one major relic, and dozens of lesser-known relics. Because of their sacred and economic value, every church wanted an important relic, and a black market boomed with fake and stolen goods.

Portal, Cathedral of Saint Lazare, Autun, 12th century (photo: Patrick, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Accommodating crowds

Pilgrimage churches were constructed with some special features to make them particularly accessible to visitors. The goal was to get large numbers of people to the relics and out again without disturbing the Mass in the center of the church. A large portal that could accommodate the pious throngs was a prerequisite. Generally, these portals would also have an elaborate sculptural program, often portraying the Second Coming—a good way to remind the weary pilgrim why they made the trip!

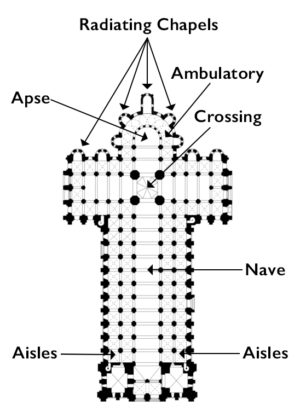

A pilgrimage church generally consisted of a double aisle on either side of the nave (the wide hall that runs down the center of a church). In this way, the visitor could move easily around the outer edges of the church until reaching the smaller apsidioles or radiating chapels. These are small rooms generally located off the back of the church behind the altar where relics were often displayed. The faithful would move from chapel to chapel, venerating each relic in turn.

Left: Nave, Tournus Cathedral, 11th century (photo: Christophe.Finot, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: Groin vaults, Robert de Luzarches, Thomas de Cormont, and Renaud de Cormont, Amiens Cathedral, begun 1220, Amiens, France (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Thick walls, small windows

Romanesque churches were dark. This was in large part because of the use of stone barrel-vault construction. This system provided excellent acoustics and reduced fire danger. However, a barrel vault exerts continuous lateral (outward pressure) all along the walls that support the vault.

This meant the outer walls of the church had to be extra thick. It also meant that windows had to be small and few. When builders dared to pierce walls with additional or larger windows, they risked structural failure. Churches did collapse.

Later, the masons of the Gothic period replaced the barrel vault with the groin vault, which carries weight down to its four corners, concentrating the pressure of the vaulting, and allowing for much larger windows.