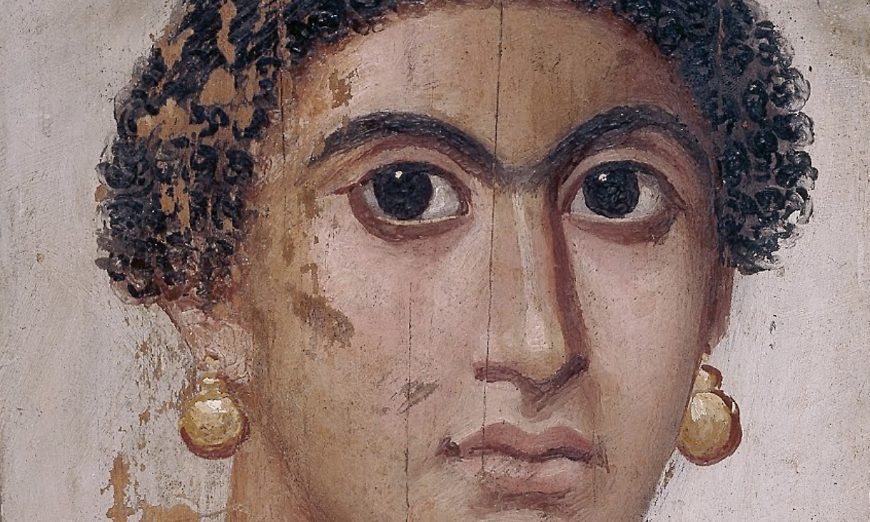

Panel with Painted Image of Isis, 2nd century C.E. (Egypt), tempera on wood, 40 x 19.1 x 13 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

How do images survive cultural transformation, and what do they carry with them as they change? A painted wooden panel of the goddess Isis, once used for domestic devotion in late antique Egypt, offers a powerful glimpse into the fluidity of religious art in a world on the cusp of profound change. Made from two vertical pieces of sycamore wood and originally fitted with hinges, this modest yet evocative object likely formed part of a diptych or triptych. Though small in scale, it holds within its frame the layered identities of Greco-Roman, Egyptian, and emerging Christian traditions.

Panel with Painted Image of Serapis, 2nd century C.E. (Egypt), tempera on wood, 39.1 x 19.1 x 1.6 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Together with a related panel of Serapis in the Getty Museum’s collection, the Isis portrait invites us to rethink the boundaries between ancient and Christian devotional imagery. Rather than separate, self-contained traditions, these objects suggest a long, adaptive continuum, one in which sacred forms, materials, and visual strategies endured and evolved across a shifting religious landscape.

Panel with Painted Image of Isis, 2nd century C.E. (Egypt), tempera on wood, 40 x 19.1 x 13 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Isis and the visual language of late antiquity

Isis, a goddess revered across the ancient Mediterranean for her associations with healing, protection, and motherhood, is depicted here in a manner deeply informed by both Roman and Egyptian traditions. Her face is rendered with soft, naturalistic shading, large almond-shaped eyes, and a solemn, contemplative gaze. These stylistic choices were not unique to depictions of Isis but were part of a broader visual vocabulary shared across late antique paintings, including Christian icons. Such visual continuity suggests a deep cultural dialogue between pagan and emerging Christian aesthetics during this transitional era.

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, 6th or early 7th century, encaustic on wood, 68.5 x 49.5 cm (The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In fact, the portrait of Isis bears striking resemblance to later images of the Virgin Mary produced in Byzantine and Orthodox Christian contexts, such as those at The Sinai Monastery, including Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George. The iconography of maternal divinity and frontal intimacy found in this panel would become central to Christian devotional art in centuries to come. This continuity underscores how early Christian artists may have consciously drawn upon familiar visual motifs to ease the transition to new forms of worship (from polytheistic religions to Christianity). The syncretism visible in this panel speaks to the shared emotional register of sacred art across religious boundaries.

Portable Icon with the Virgin Eleousa, early 1300s (Byzantine; probably made in Constantinople), miniature mosaic set in wax on wood panel, with gold, multicolored stones, and gilded copper, 11.2 x 8.6 x 1.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Devotion in the domestic sphere

Unlike monumental cult statues or images found in temples, this small panel was likely intended for private, household worship. Its hinged design suggests it could be closed for protection or carried for personal use, an early expression of the portability that would later characterize Christian icons. The intimacy of its scale and material reinforces the idea of everyday spiritual practice: a divine presence not confined to public rituals but integrated into daily life.

This mode of domestic devotion crosses religious lines. Just as later Christian icons were venerated in monastic cells and family homes, earlier religious objects like this one fulfilled similar emotional and spiritual needs.

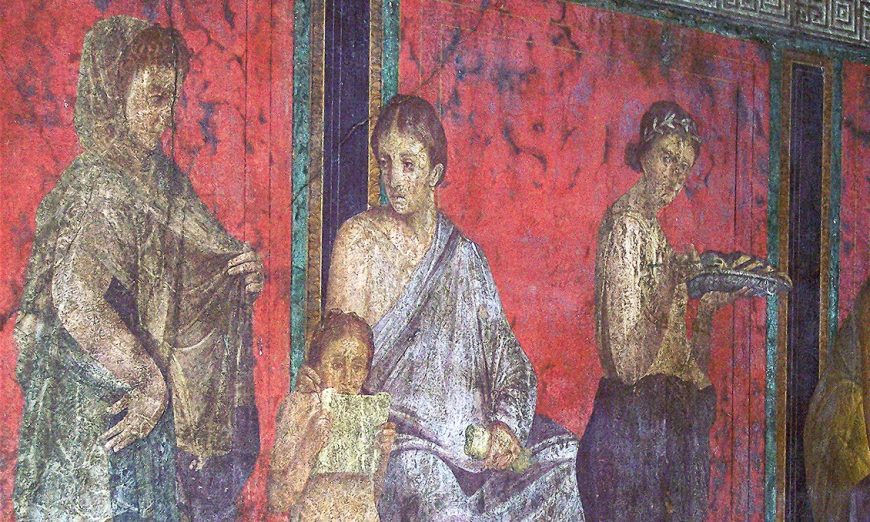

North Africa’s artistic legacy

Egypt, part of the Roman Empire, was a vibrant center of cultural and artistic production in antiquity. Artists there worked in a region shaped by centuries of exchange, blending local traditions with imperial aesthetics. The artistic traditions of North Africa influenced Christian visual culture far beyond the region. Workshops in Egypt developed techniques, panel painting, modeling in tempera and encaustic, and devotional formats, that would travel through trade networks and ecclesiastical institutions into Byzantine territories. Images of the Virgin Mary and Christ Pantocrator owe much to these precedents, as do later devotional practices centered around panel icons.

Continuity, change, and cultural adaptation

By the 7th century C.E., political and religious transformations, including the Islamic conquests, reshaped North Africa’s artistic landscape. Yet the visual strategies developed there remained. The painted portrait of Isis offers a lens onto this moment of continuity and transformation. It helps us understand not only the development of icon painting but also how images migrate, evolve, and persist through time and belief systems.

Rather than representing a rupture between polytheistic practices and Christianity, the Isis panel reminds us of the cultural and material continuities that defined the late antique world. The image transcends its religious origins to become part of a shared Mediterranean visual language, rooted in North Africa, and resonant far beyond it. Its frontal pose evocation of divine presence continued to inform sacred art long after the decline of Isis worship. In this way, the painting reveals the adaptive power of visual forms to navigate religious change, maintaining symbolic potency even as their theological contexts shift. It is a testament to the role of art in shaping and reflecting collective spiritual memory.