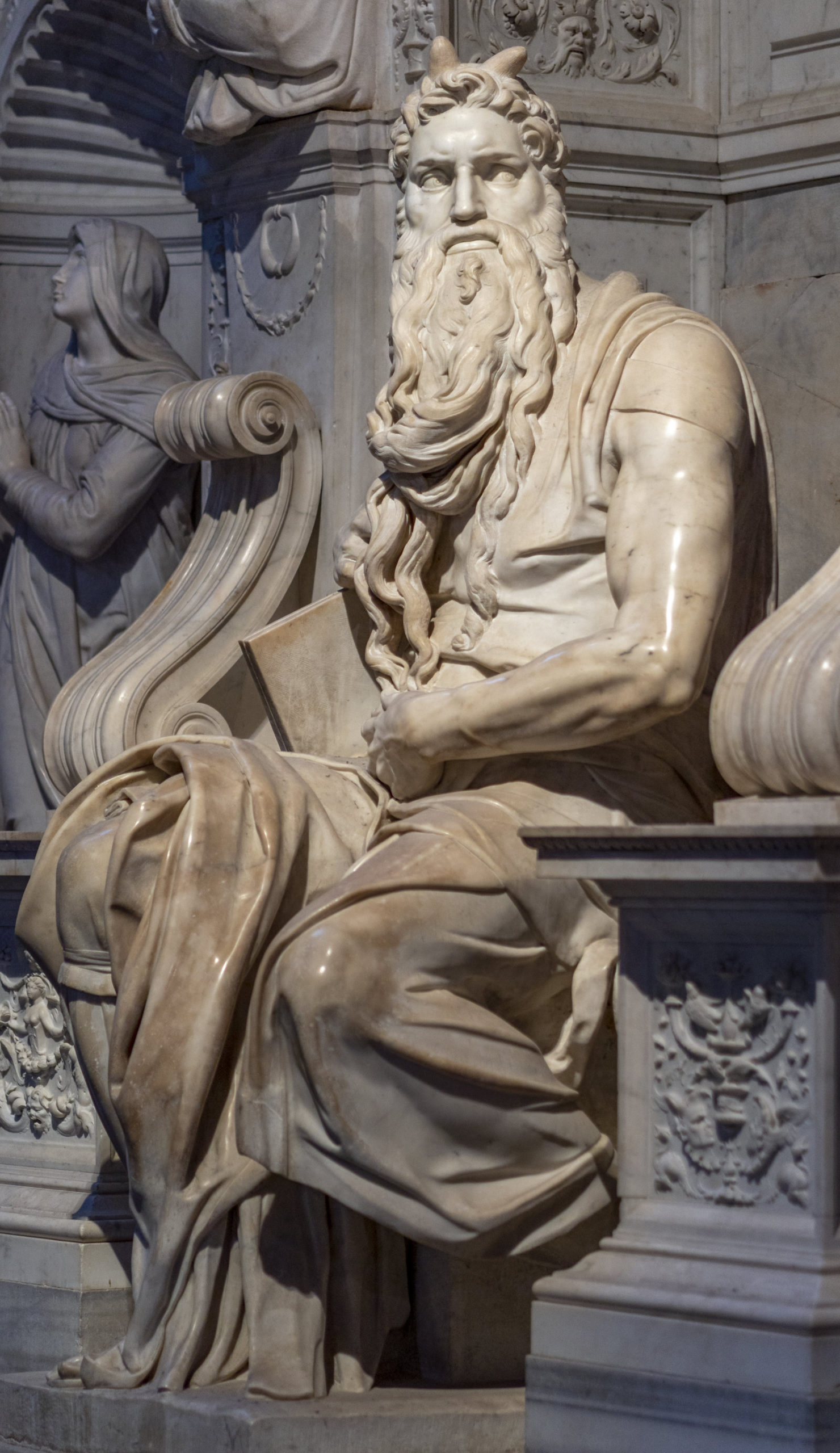

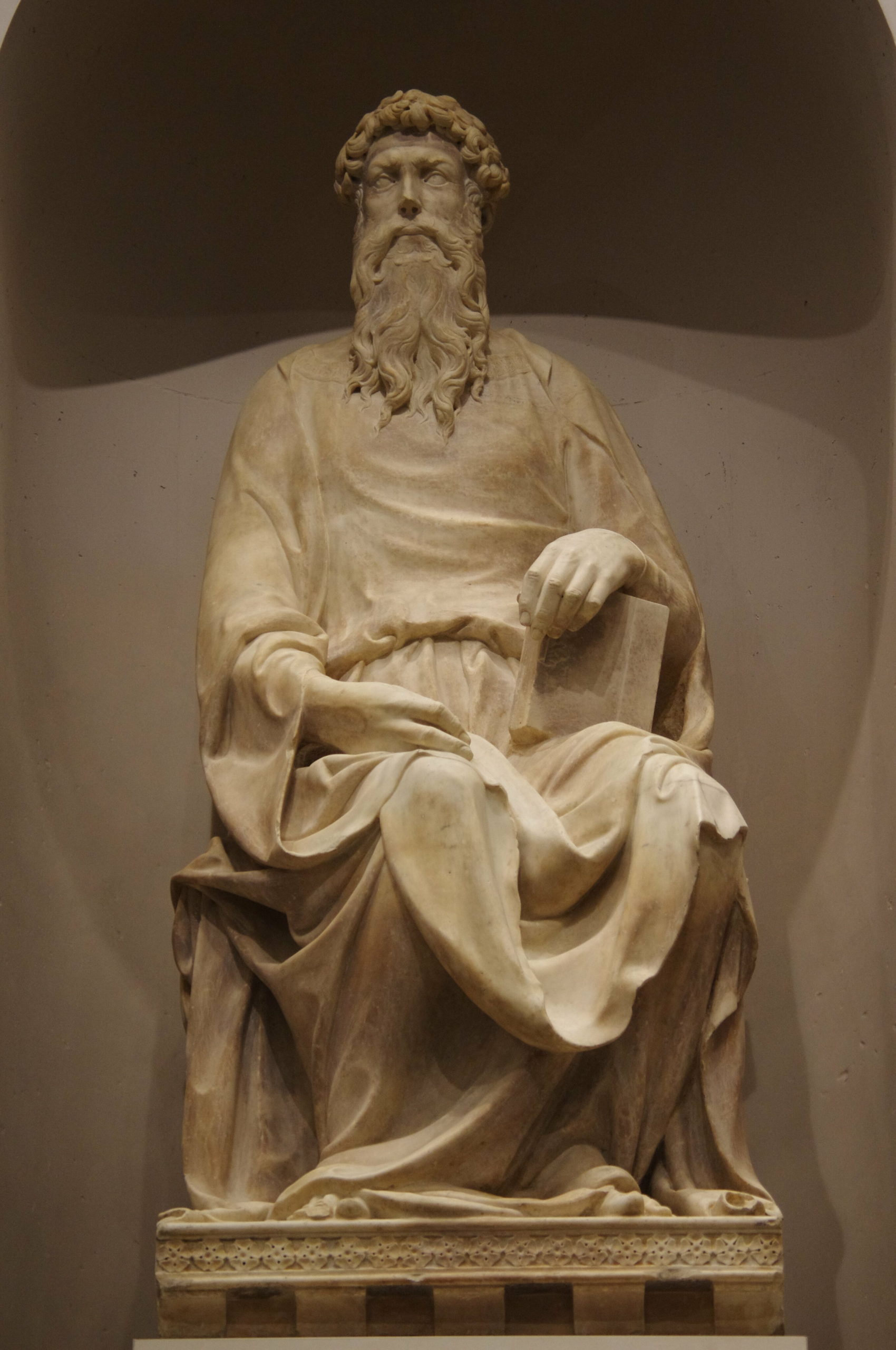

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Moses, 1513-15, Carrara marble, 254 cm (8 feet, 3 inches) high, Tomb of Pope Julius II (della Rovere), 1505-45, San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Saint Peter in Chains, in Rome, looking at the tomb of the Pope Julius II.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:14] One of Michelangelo’s biographers referred to this project as “the tragedy of the tomb,” and that’s because it just went on and on and on.

Dr. Zucker: [0:23] Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to produce a tomb of an unprecedented scale. He wanted as many as 47 over-life-size figures.

Dr. Harris: [0:34] And a multi-storied freestanding structure. It was very common for rulers to plan their tombs before their death, so Julius II wasn’t doing anything unusual, but Julius was a very ambitious pope.

Dr. Zucker: [0:48] He was known as the Warrior Pope, and actually led military campaigns to reclaim lands that had once been controlled by the Church. He also was responsible for the building of the new Saint Peter’s Basilica.

Dr. Harris: [1:00] That was the destination for this tomb originally. It wasn’t supposed to be here, a church that was actually associated with Julius’ family. So Michelangelo impresses everyone with his sculpture of David. He gets called to Rome by Pope Julius II, and this is first project the pope gives him.

Dr. Zucker: [1:19] This is a wall tomb, and it’s much smaller than what was originally envisioned. In addition, there is only one large-scale figure by Michelangelo, and that is the central figure, the figure of Moses.

Dr. Harris: [1:29] Two other figures were completed for the tomb, but those are in the Louvre, the “Dying Slave” and the “Rebellious Slave.”

Dr. Zucker: [1:35] Those were to be two of many figures of the male nude known as the “Slaves” or the “Bound Figures.” In the Academy in Florence, there are actually a number of unfinished sculptures that Michelangelo had originally intended for this tomb.

Dr. Harris: [1:47] There’s some confusion about exactly what Michelangelo meant by these slaves or captives. One of his biographers offered the interpretation that these represent the arts — the arts of, for example, painting, sculpture, and architecture — that Julius II was such a great patron of that would be captive because of Julius II’s death.

Dr. Zucker: [2:08] A kind of mourning, a kind of agony, that they had lost their greatest benefactor.

Dr. Harris: [2:12] There were herm figures. There were figures of Victory that were meant for the tomb. There were also supposed to be seated figures in addition to Moses of Paul and of the active and contemplative life, so this is an incredibly ambitious tomb.

Dr. Zucker: [2:26] Most importantly, Michelangelo was to produce a portrait of Julius II, an effigy. It’s interesting that Michelangelo actually avoided sculpting that particular figure and instead focused on the Old Testament prophet Moses.

Dr. Harris: [2:39] When you sculpt someone’s tomb, the most important figure would be a portrait of that person whose tomb it is, but typical for Michelangelo, he’s much more interested in the human body than he is in capturing the likeness of an individual person.

Dr. Zucker: [2:54] Here in the representation of Moses, we see Michelangelo’s interest in the power of the human body, but also his interest in the interior self.

Dr. Harris: [3:03] Power is a really good word here. This is a seated figure. Sitting is not a very active pose, but Michelangelo has filled this figure with energy and drama and tension.

Dr. Zucker: [3:17] Look at the way his left foot pushes back, as if he’s going to propel himself up. Look at the latent power in those arms, in those legs. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a figure that has more potential energy.

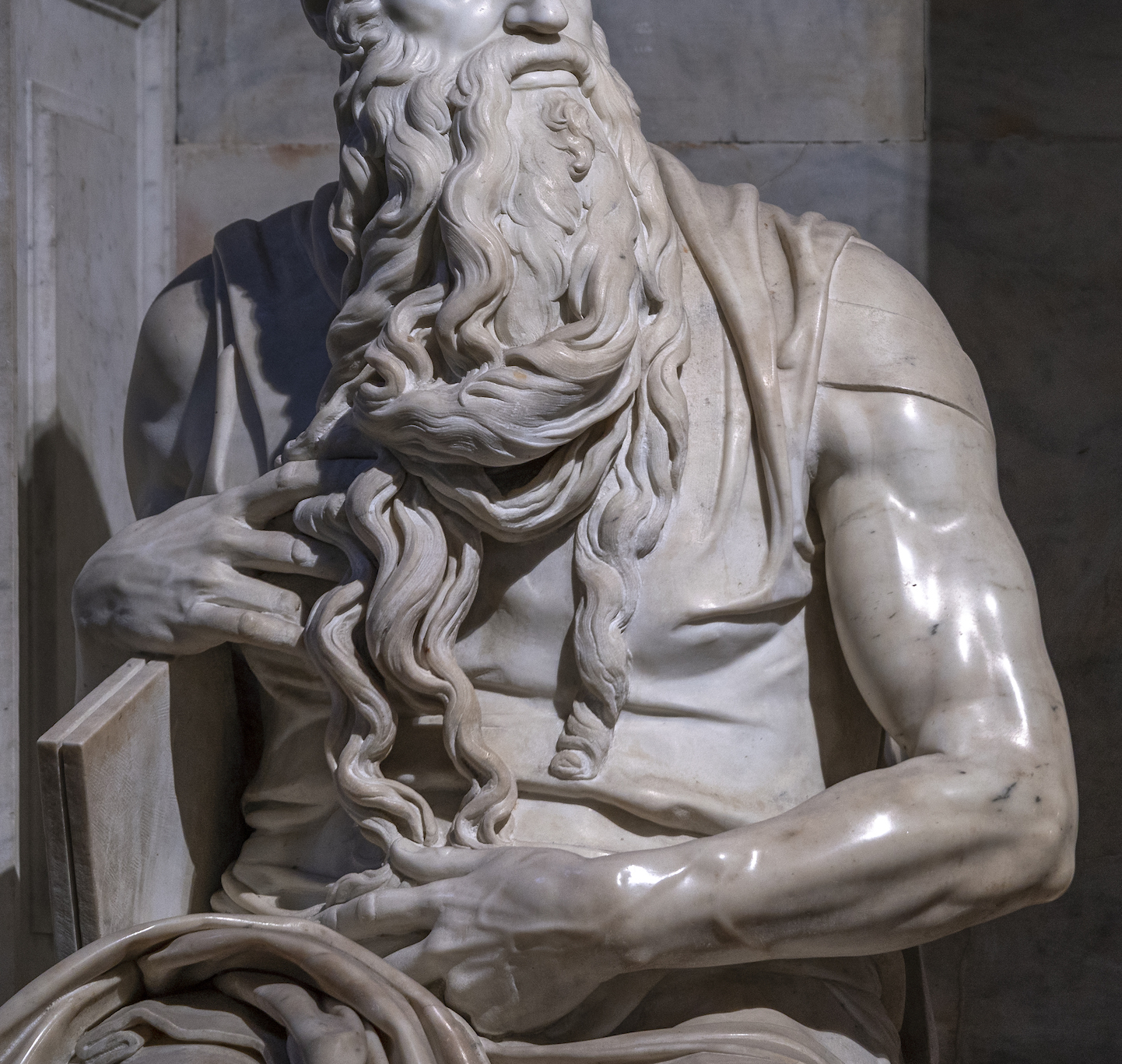

Dr. Harris: [3:30] As he pulls his left leg back, his hips shift naturally in that direction, but his shoulders turn slightly in the opposite direction, activating the figure, giving it a spiral tension, and then his head shifts in the opposite direction but the beard pulls again opposite to the direction of the head. Each part of the body moves in opposition to the part next to it.

Dr. Zucker: [3:54] That opposition is wonderfully clear in that his focus is to the left. He’s looking into the distance. Remember, this would have been some 15 feet off the ground.

Dr. Harris: [4:04] We would have been looking up at him, very different than the way we’re looking at him today. But it’s that gaze; just like with his figure of the David, we have a sense of the presence of something that Moses is looking out to.

Dr. Zucker: [4:16] So what is that?

Dr. Harris: [4:18] One interpretation is that Moses is looking at the Israelites worshiping the golden calf. He’s come down from receiving the 10 Commandments from God.

Dr. Zucker: [4:28] Moses is the great symbol of monotheism, but the Israelites have reverted to the polytheism of ancient Egypt.

Dr. Harris: [4:34] Perhaps that is the focus of that very angry gaze, although there is also a sense that the tablets seem to be slipping from between his torso and his arm. There is a question of what moment this is in the narrative. This problem pinning down what moment this is or what the Captives or Slaves represent, this is not unusual for Michelangelo.

Dr. Zucker: [4:59] He may not be representing a specific moment. He may be creating a distillation, a figure that can represent the continuity of that story over time.

Dr. Harris: [5:06] One art historian has talked about the ways that perhaps Michelangelo, in Moses and in the Slaves, and in other work, is interested in this idea of binding, of releasing the figure from within the stone.

[5:19] This is a theme in Michelangelo’s work, and even that drapery that goes over the knee gives us a sense of uncovering, of removing something to find something underneath, which is the process of carving stone.

Dr. Zucker: [5:33] It’s important to remember also that the horns at the top of Moses’ head would only just be visible if we were looking up at the figure, as opposed to across at the figure.

Dr. Harris: [5:41] We recognize figures by their attributes, and the horns were an attribute of Moses. This comes from a mistranslation from the Hebrew word for “rays of light.” Traditionally, Moses just became represented with these horns.

[5:56] Michelangelo was very excited to work on the tomb. It’s an enormous commission for the pope with close to 50 figures. Michelangelo spends much of 1505, actually, quarrying the marble.

[6:08] So he’s really invested in this project, but Pope Julius II takes him off the project for the tomb and asks him to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which Michelangelo does reluctantly at first, but Michelangelo, through paint, explores the male nude, which will become so important when he returns to the subject of the tomb of Pope Julius II.

Dr. Zucker: [6:30] In the end, Moses became the central figure in the tomb for Julius, but it’s important to remember that the tomb we see now is just a shadow of Julius II’s initial ambitions.

[6:40] [music]

When Michelangelo finished sculpting David, it was clear that this was quite possibly the most beautiful figure ever created—exceeding the beauty even of Ancient Greek and Roman sculptures. Word of David reached Pope Julius II in Rome, and he asked Michelangelo to come to Rome to work for him. The first work Pope Julius II commissioned from Michelangelo was a tomb for the pope.

This may seem a bit strange to us today, but great rulers throughout history have planned fabulous tombs for themselves while they were still alive—they hoped to ensure that they would be remembered forever.

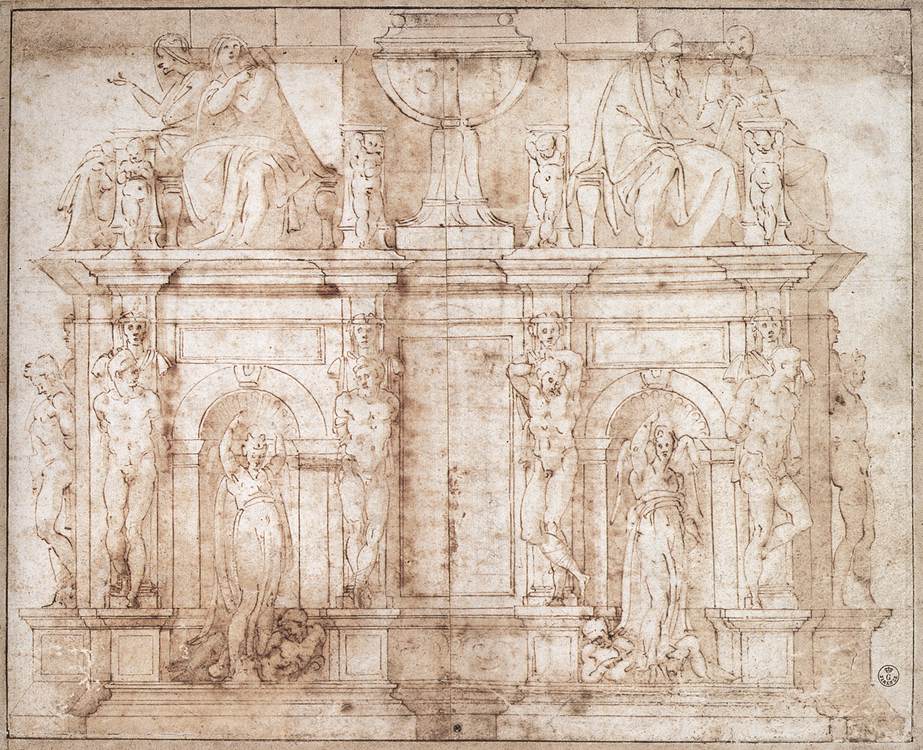

Michelangelo, Drawing for the Tomb of Pope Julius II, c. 1505, pen and ink (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Web Gallery of Art)

When Michelangelo began the Tomb of Pope Julius II, his ideas were quite ambitious. He planned a two-story structure decorated with more than 20 sculptures—each of these life sized. This was more than one person could do in a lifetime.

Michelangelo, Tomb of Pope Julius II, 1505–45, marble (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to pause his work on the tomb to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and he was never able to complete his plan for the tomb. After experiencing trouble with Julius’ heirs, Michelangelo eventually completed a much scaled-down version of the tomb, which was installed in San Pietro in Vincoli (and not in St. Peter’s Basilica as planned).

Moses

Moses is an imposing figure—he is nearly eight feet high sitting down! He has enormous muscular arms and an angry, intense look in his eyes. Under his arms he carries the tablets of the law—the stones inscribed with the Ten Commandments that he has just received from God on Mt. Sinai. You might marvel at Moses’ horns. This comes from a mistranslation of a Hebrew word that described Moses as having rays of light coming from his head.

Moses (detail), Michelangelo, Tomb of Pope Julius II, c. 1513–15, marble, 235 cm (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In this story from the Old Testament book of Exodus, Moses leaves the Israelites, who he has just delivered from slavery in Egypt, to go to the top of Mt. Sinai. When he returns, he finds that the Israelites have constructed a golden calf to worship and make sacrifices to. They have, in other words, been acting like the Egyptians and worshipping a pagan idol.

Michelangelo, Moses from Tomb of Pope Julius II, c. 1513–15, marble, 235 cm (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One of the commandments Moses received is “Thou shalt not make any graven images,” so when Moses sees the Israelites worshipping this idol and betraying the one and only God who has just delivered them from slavery, he throws down the tablets and breaks them. Here is the passage from the Hebrew Bible:

Then Moses turned and went down the mountain. He held in his hands the two stone tablets inscribed with the terms of the covenant. They were inscribed on both sides, front and back. These stone tablets were God’s work; the words on them were written by God himself. When Joshua heard the noise of the people shouting below them, he exclaimed to Moses, “It sounds as if there is a war in the camp!” But Moses replied, “No, it’s neither a cry of victory nor a cry of defeat. It is the sound of a celebration.” When they came near the camp, Moses saw the calf and the dancing. In terrible anger, he threw the stone tablets to the ground, smashing them at the foot of the mountain. (Exodus 32: 15–19)

We can see the figure’s pent-up energy. The entire figure is charged with thought and energy. It is not entirely clear what moment of the story Michelangelo shows us. Moses sits with the tables of the ten commandments under his right arm. Is he about to rise in anger after seeing the Israelites worshiping the golden calf?

Moses (detail), Michelangelo, Tomb of Pope Julius II, c. 1513–15, marble, 235 cm (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Moses is not simply sitting down; his left leg is pulled back to the side of his chair as though he is about to rise. And because this leg is pulled back, his hips also face left. Michelangelo, to create an interesting, energetic figure—where the forces of life are pulsing throughout the body—pulls the torso in the opposite direction. And so his torso faces to his right. And because the torso faces to the right, Moses turns his head to the left, and then pulls his beard to the right.

Michelangelo, Moses from Tomb of Pope Julius II, c. 1513–15, marble, 235 cm (San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Michelangelo managed to create an intense, energetic figure even though Moses is seated. While the marble itself is still, it seems as though his beard is moving and flowing and that his muscular arms and torso are about to shift.

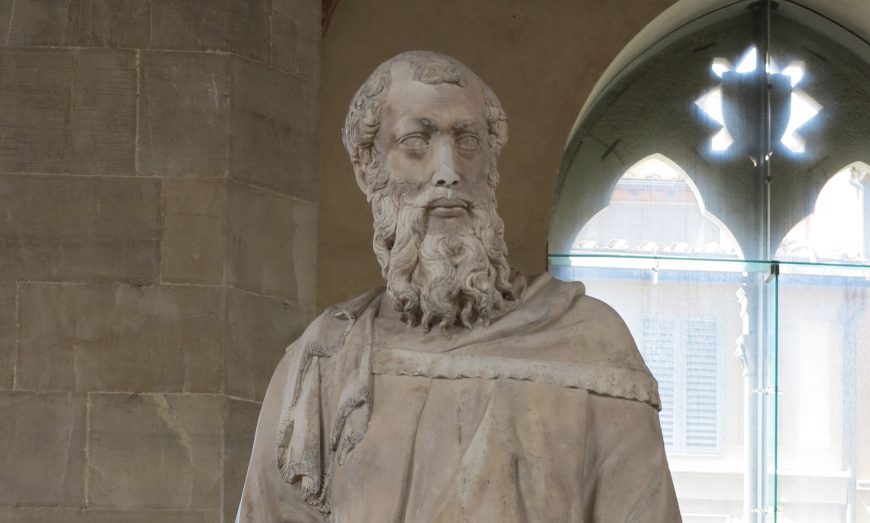

Donatello, St. John, c. 1408–15, marble (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence; photo: dvdbramhall, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In comparing Michelangelo’s Moses to an Early Renaissance sculpture by Donatello, it is easy to see the difference between the Early and High Renaissance ideals. Donatello’s relaxed figure St. John really lacks the power and life of Michelangelo’s sculpture. Think about how you’re sitting right now at the computer. Perhaps your legs are crossed, as mine are as I write this. What about if you were not at the computer? And what to do with the hands? You can see that this could be a rather uninteresting position. Yet Michelangelo has given the entire figure energy and movement, even in a sitting position.

In Michelangelo’s dynamic figure of Moses we have a clear sense of the prophet and his duty to fulfill God’s wishes. Moses is not a passive figure from the distant biblical past, but a living, breathing, present figure that reflects the will and might of God.