God created the world in seven days, but it took Michelangelo four years to depict it on this remarkable ceiling.

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome) (photo: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY 3.0)

Visiting the Chapel

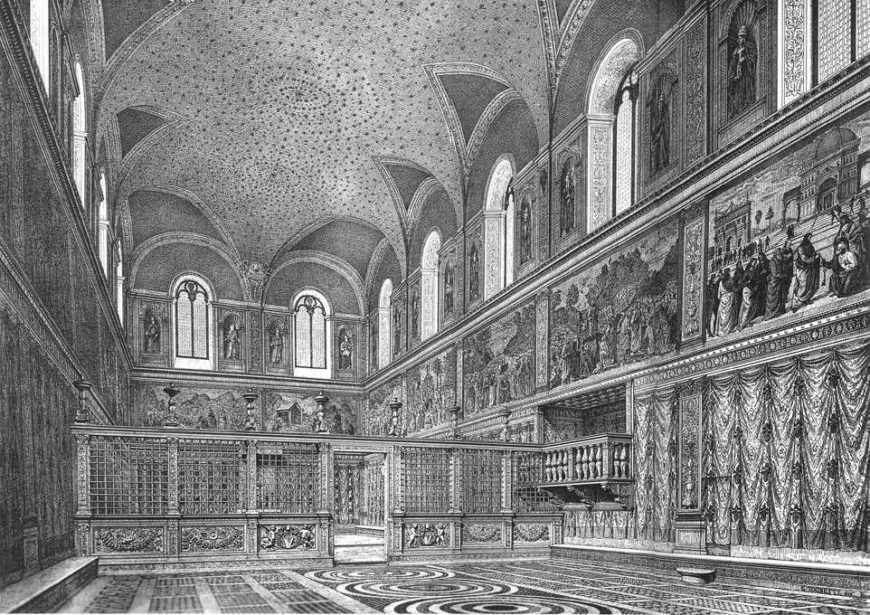

To any visitor of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, two features become immediately and undeniably apparent: 1) the ceiling is really high up, and 2) there are a lot of paintings up there. Because of this, the centuries have handed down to us an image of Michelangelo lying on his back, wiping sweat and plaster from his eyes as he toiled away year after year, suspended hundreds of feet in the air, begrudgingly completing a commission that he never wanted to accept in the first place.

Fortunately for Michelangelo, this is probably not true. But that does nothing to lessen the fact that the frescoes, which take up the entirety of the vault, are among the most important paintings in the world.

For Pope Julius II

Michelangelo began to work on the frescoes for Pope Julius II in 1508, replacing a blue ceiling dotted with stars. Originally, the pope asked Michelangelo to paint the ceiling with a geometric ornament, and place the twelve apostles in spandrels around the decoration. Michelangelo proposed instead to paint the Old Testament scenes now found on the vault, divided by the fictive architecture that he uses to organize the composition.

![Diagram of the subjects of the Sistine Chapel [1] (photo: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/1280px-Sistine_Chapel_ceiling_diagram.svg-870x468.png)

Diagram of the subjects of the Sistine Chapel [1] (photo: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The subject of the frescoes

The narrative begins at the altar and is divided into three sections. In the first three paintings, Michelangelo tells the story of The Creation of the Heavens and Earth; this is followed by The Creation of Adam and Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden; finally is the story of Noah and the Great Flood.

Ignudi, or nude youths, sit in fictive architecture around these frescoes, and they are accompanied by prophets and sibyls (ancient seers who, according to tradition, foretold the coming of Christ) in the spandrels. In the four corners of the room, in the pendentives, one finds scenes depicting the Salvation of Israel.

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY 3.0)

The Deluge

Although the most famous of these frescoes is without a doubt, The Creation of Adam, reproductions of which have become ubiquitous in modern culture for its dramatic positioning of the two monumental figures reaching towards each other, not all of the frescoes are painted in this style. In fact, the first frescoes Michelangelo painted contain multiple figures, much smaller in size, engaged in complex narratives. This can best be exemplified by his painting of The Deluge.

Michelangelo, The Deluge (detail), Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome)

In this fresco, Michelangelo has used the physical space of the water and the sky to separate four distinct parts of the narrative. On the right side of the painting, a cluster of people seeks sanctuary from the rain under a makeshift shelter. On the left, even more people climb up the side of a mountain to escape the rising water. Centrally, a small boat is about to capsize because of the unending downpour. And in the background, a team of men work on building the arc—the only hope of salvation.

Michelangelo, Creation scenes, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Up close, this painting confronts the viewer with the desperation of those about to perish in the flood and makes one question God’s justice in wiping out the entire population of the earth, save Noah and his family, because of the sins of the wicked. Unfortunately, from the floor of the chapel, the use of small, tightly grouped figures undermines the emotional content and makes the story harder to follow.

A shift in style

In 1510, Michelangelo took a yearlong break from painting the Sistine Chapel. The frescoes painted after this break are characteristically different from the ones he painted before it, and are emblematic of what we think of when we envision the Sistine Chapel paintings. These are the paintings, like The Creation of Adam, where the narratives have been pared down to only the essential figures depicted on a monumental scale. Because of these changes, Michelangelo is able to convey a strong sense of emotionality that can be perceived from the floor of the chapel. Indeed, the imposing figure of God in the three frescoes illustrating the separation of darkness from light and the creation of the heavens and the earth radiates power throughout his body, and his dramatic gesticulations help to tell the story of Genesis without the addition of extraneous detail.

The Sibyls

Michelangelo, Delphic Sibyl, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY 3.0)

This new monumentality can also be felt in the figures of the sibyls and prophets in the spandrels surrounding the vault, which some believe are all based on the Belvedere Torso, an ancient sculpture that was then, and remains, in the Vatican’s collection. One of the most celebrated of these figures is the Delphic Sibyl.

The overall circular composition of the body, which echoes the contours of her fictive architectural setting, adds to the sense of the sculptural weight of the figure.

Her arms are powerful, the heft of her body imposing, and both her left elbow and knee come into the viewer’s space. At the same time, Michelangelo imbued the Delphic Sibyl with grace and harmony of proportion, and her watchful expression, as well as the position of the left arm and right hand, is reminiscent of the artist’s David.

Michelangelo, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1511, fresco, part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (Vatican Museums; photo: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY 3.0)

The Libyan Sibyl is also exemplary. Although she is in a contorted position that would be nearly impossible for an actual person to hold, Michelangelo nonetheless executes her with a sprezzatura (a deceptive ease) that will become typical of the Mannerists who closely modelled their work on his.

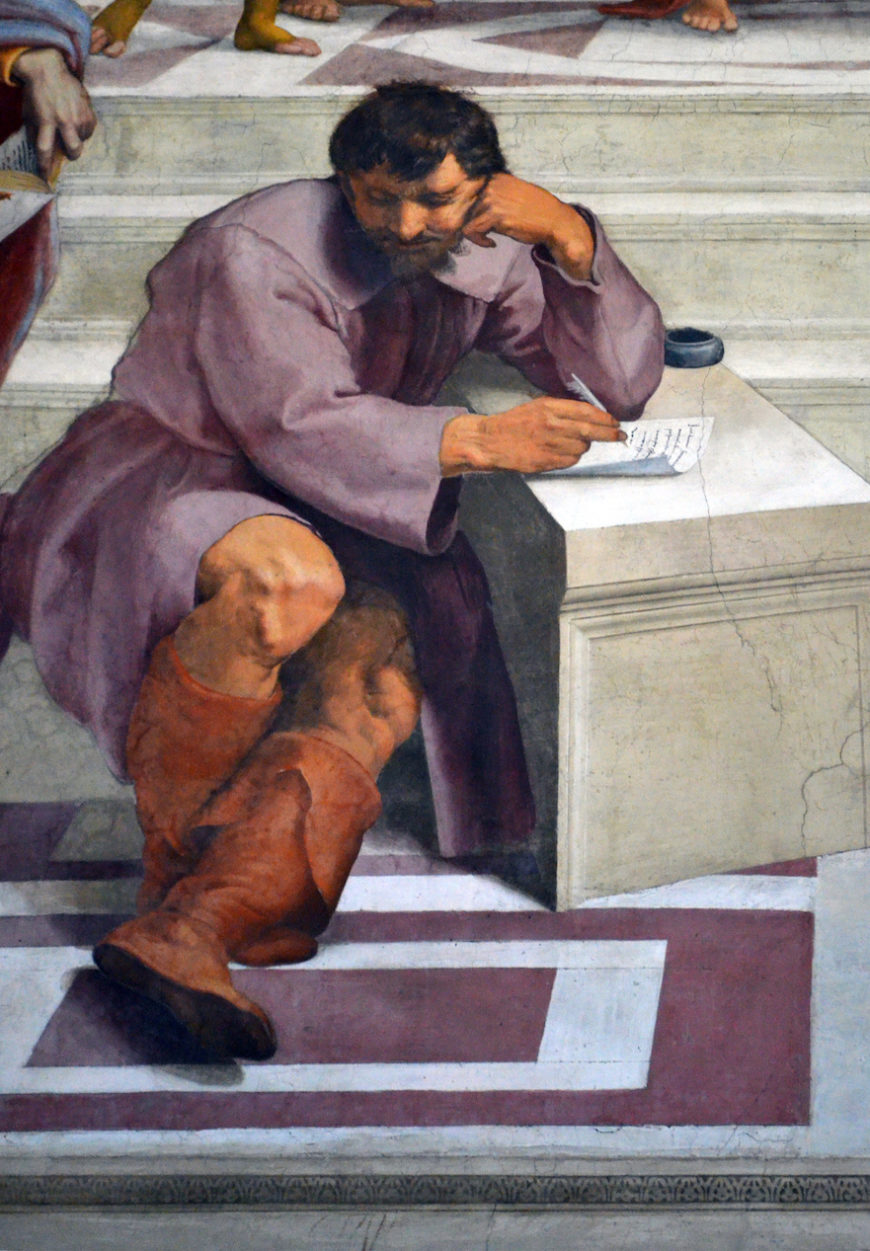

It is no wonder that Raphael, struck by the genius of the Sistine Chapel, rushed back to his School of Athens in the Vatican Stanze and inserted Michelangelo’s weighty, monumental likeness sitting at the bottom of the steps of the school.

Heraclitus, whose features are based on Michelangelo’s and his seated pose is based on the prophets and sibyls from Michelangelo’s frescoes on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (detail), Raphael, School of Athens, 1509–11, Stanza della Segnatura (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Darafsh, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Legacy

Michelangelo completed the Sistine Chapel in 1512. Its importance in the history of art cannot be overstated. It turned into a veritable academy for young painters, a position that was cemented when Michelangelo returned to the chapel twenty years later to execute the Last Judgment fresco on the altar wall.

The chapel recently underwent a controversial cleaning, which has once again brought to light Michelangelo’s jewel-like palette, his mastery of chiaroscuro, and additional iconological details which continue to captivate modern viewers even five hundred years after the frescoes’ original completion. Not bad for an artist who insisted he was not a painter.

Notes:

[1] The diagram neglects the subject of the four corner paintings indicated in lavender. The four scenes represent the salvation of the Jewish people.

Additional resources

This painting at the Vatican Museums

Panorama of the Sistine Chapel from the Vatican

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, which has tremendous importance to Catholicism. This is were the pope will lead mass, but perhaps most famously, this is the room that the College of Cardinals uses to decide the next pope.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:19] Every surface of this space is decorated, from the beautiful mosaics on the floor, the walls are painted with frescoes by early Renaissance artists, the wall behind the altar was painted by Michelangelo later in his life, and then of course, the ceiling.

Dr. Zucker: [0:36] Everybody is looking up. Their necks are craned, and of course, it’s magnificent. We’re here in the late afternoon on a day in early July. The light is diffuse, and it makes those frescoed figures feel so dimensional, they feel like sculpture.

Dr. Harris: [0:53] You can imagine what it was like when this was unveiled in 1512 after Michelangelo had worked on it for years. How different, how revolutionary Michelangelo’s figures seemed.

Dr. Zucker: [1:04] He was, first and foremost, a sculptor, and it wasn’t actually until a relatively recent cleaning that we knew his brilliance as a colorist. For him, line and drawing and the act of carving figures out of paint was primary and you have this extraordinary ability to render both strength and elegance simultaneously.

Dr. Harris: [1:28] They have a massiveness and a presence that is charismatic, but there’s also a sense of elegance and ideal beauty. Let’s describe what we’re looking at.

Dr. Zucker: [1:40] Probably the most important are the series of nine scenes that move across the central panels.

Dr. Harris: [1:47] Those are framed by a painted architectural framework that looks real. It doesn’t look like paint. We start with the creation of the world. God separating light from darkness.

Dr. Zucker: [2:00] I love that scene. This primordial God, light on one side of His body and the darkness of night on the other. This initial separation and division to create order in the universe.

Dr. Harris: [2:11] Then we move through to the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve…

Dr. Zucker: [2:15] Or the separation of the sexes.

Dr. Harris: [2:17] …and the creation of God’s most perfect creature, human beings, and then the fall of human beings.

Dr. Zucker: [2:23] In a sense, the separation of good and evil.

Dr. Harris: [2:26] Man and woman disobeying God, causing the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden. Then, [at] the far end by the entrance, we see the scenes of Noah.

Dr. Zucker: [2:37] These are all scenes from the first book of the Bible, from the Book of Genesis. It’s so interesting because, of course, this is a Catholic church, and yet we don’t see images of Christ, but these Old Testament scenes lay the foundation for the coming of Christ.

Dr. Harris: [2:53] Christ is present in other ways. Not only does the disobedience of Adam and Eve make the coming of Christ necessary, but when we look on either side of those central scenes, we see the prophets and the sibyls who predicted the coming of a savior for mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [3:12] The image of the Libyan sibyl that we’re sitting directly across from is spectacularly beautiful. Sibyls are these ancient pagan soothsayers who can foresee the future, and according to the Catholic tradition foretell the coming of Christ. Look at the Libyan sibyl, look at the power of her body, and look at the elegance with which she twists and turns.

[3:36] There is that sense of potential in the way that her toe just reaches down and touches the ground, but seems as if she is in the act of moving and possibly of standing.

Dr. Harris: [3:47] There’s a presence and drama to these figures, to the Libyan sibyl especially. She twists her body in an almost impossible way. We can see Michelangelo has articulated every muscle in the back, and in fact we know that he used a male model for that figure.

Dr. Zucker: [4:04] I’m so taken with the color here. When I first studied Michelangelo, we spoke only of line, of sculptural form, but of course after the dramatic cleaning of the Sistine Chapel, those original colors, their brilliance, their delicacy, came out.

Dr. Harris: [4:19] We see purples and golds and oranges and blues and greens.

Dr. Zucker: [4:24] She, of course, is reaching back, and presumably that’s a book of prophecy that she holds, and there’s a look of confidence and knowing on her face. The absolute clarity with which she knows that Christ will come.

Dr. Harris: [4:37] Sitting on the architecture framework on the four corners of all of the central scenes are male nude figures that we refer to as “ignudi.”

Dr. Zucker: [4:47] I think this is really important because Michelangelo is not painting simply sacred paintings, but is creating this enormously complex stage set, with which to create levels of reality. For example, the Libyan sibyl seems as if she is seated amongst the architecture.

[5:06] Then set next to her are bronze figures, and then in the spandrels, as you mentioned, other scenes that seem to recede into a illusionistic distance.

Dr. Harris: [5:14] Then relief sculptures on the architecture on either side of her, and then seated above those, the ignudi. It’s so clear that we’re at this moment at the rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. Michelangelo is in Rome, he’s in the Vatican.

Dr. Zucker: [5:31] This is the High Renaissance. It’s so interesting to compare the optimism, the elegance, the nobility of the figures on the ceiling with the far darker and more pessimistic view that Michelangelo will paint decades later on the back wall, the “Last Judgment”.

Dr. Harris: [5:48] That’s right. There’s a big difference between 1512 when Michelangelo completes the ceiling and when he begins the “Last Judgment.” The Protestant Reformation has begun and the church is under attack.

Dr. Zucker: [6:01] Michelangelo’s world had been shattered, but when you look at the ceiling you see instead all of the optimism, all of the intellectual and emotional power that characterizes the High Renaissance in all of its newfound appreciation for the ancient world. This was a moment of incredible promise, and all of that comes shining through these figures.

Dr. Harris: [6:25] Let’s not forget that just a few doors away, simultaneously, Raphael is painting the frescoes in the Papal Palace. What a moment in Rome.

[6:35] [music]