Reconstruction of the mural from a room in Çatalhöyük, c. 6150 B.C.E. (photo: Panegyrics of Granovetter, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A wall painting at Çatalhöyük, Turkey (c. 6150 B.C.E.) has been interpreted as presenting an image of an exploding volcano. This work is often cited as the earliest landscape — that is, an image where the main subject is the natural world, itself, rather than people or other figures doing something in that landscape.

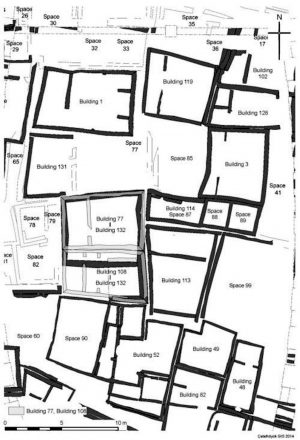

North Area at Çatalhöyük, figure created for the Catalohoyuk Research Project by Camilla Mazzucato, in AIan Hodder and Arkadiusz Marciniak, eds., Assembling Çatalhöyük (Routledge, 2017)

An early image of a volcano?

Çatalhöyük is among the earliest surviving cities, and is the largest Neolithic city to have been found, originally housing as many as 10,000 people, actively engaged in trade for daily and luxury materials. Several of the buildings have wall paintings showing conflicts with the natural world. If this painting does show a volcano, then it depicts what is among the more spectacularly violent events in nature. An event of this nature would certainly capture the attention of ancient civilizations, as it captures ours, though they would likely have interpreted it through a different view of the world.

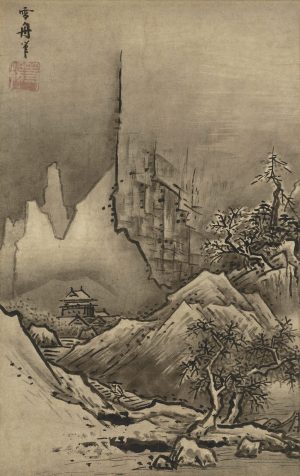

A brief look at Çatalhöyük’s overall design reveals much about this culture’s view of nature. Whereas we tend to pay a premium for homes and offices with large windows looking out onto landscapes, the homes and other structures found by archeologists at Çatalhöyük have no windows at all. This is a society more concerned with protection from the elements than with pretty views. This should not be surprising. The natural world was — and remains — a site of real danger. Here, the danger is of cataclysm rather than of grinding suffering, as in Sesshu Toyo’s Winter Landscape.

Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

In the wall painting, we see what appears to be the city spread out as if in a plan, with the wobbly, irregular rectangles representing structures. The lack of streets between them reflects the actual plan of the city — the buildings all adjoining one another, and entered through holes in the roofs. Towering over the city is a great volcano, depicted in red, arguably based on Hasan Dag, a nearby mountain with two peaks.

Or is it? It has recently been suggested that the image does not show a volcano and a city plan but rather, a leopard skin over geometric patterning. While this is a completely different — but also plausible — reading of an unclear, prehistoric image, it also points toward the dangers of the natural world, and the implicit competition between people and their environment. The leopard was a hunting competitor, as it killed the same wild goats hunted by the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük.

In either case, then, this ancient image projects a relationship between the inhabitants and the natural world outside the perimeter of their city. Really, we do not have to choose; it could be one or the other, or even could be an amalgamation, representing these two natural forces in a single image. With prehistoric art — as with all art — we rarely have final and absolute answers.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas, 90.8 x 122.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Turner’s Slave Ship — nature overpowers man

In our next image, Joseph Mallord William Turner presents the natural world not merely as hard and challenging, as Sesshu does in the image from Çatalhöyük. Nor does Turner make the violence something distant and without victims, as Sesshu does. Instead, he presents nature as a consummately terrifying, all-powerful entity, vastly overwhelming the small human figures lost within its rages.

In his Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), Turner uses energetic, visible brushstrokes, breaking up the forms and thereby intensifying the sense of chaos. There is nothing quite clear here; everything seems to be in churning motion. Even the sun, burning through the clouds, does not seem a positive force. Rather, as the most brilliant white, the brightest value in the image, it seems a sharp, almost painful cut, just to the right of the center of the image. In this way, it recalls the vertical slash just off-center to the left in Sesshu’s landscape.

Sun (detail), Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas, 90.8 x 122.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Hands (detail), Joseph Mallord William Turner, Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas, 90.8 x 122.6 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The color palette here is generally warm, but this does not lend the image a cheerful tone. Instead, the reds, oranges, and yellows are the shades of blood and bruises. This is all the more disturbing in a seascape, where we might justly expect a cool, gentle image of blues and greens and whites. It is as if the violent death of the enslaved captives has been inscribed across the whole of the sea and sky.

In the lower right hand corner, great, nightmarish fish rise to the surface in a feeding frenzy. Just to the left of center, to a degree balancing out the blazing sun, are the hands of the drowning figures, outstretched dramatically in a last, failed, futile effort to cling to the surface, and to life.

This painting was based on an account in Thomas Clarkson’s The History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade (1783), recounting an actual event in which, it seems, the captain of a ship caught in a typhoon had his “cargo” of enslaved people thrown overboard, still shackled together, in order to be able to get a reimbursement from his insurance company for those lost at sea. The oversized black chains, emphasized in a sort of hieratic scale, stand out in the foreground, just to the left of center, implausibly but powerfully remaining afloat in the turbid sea.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Jonah, c. 1885-95, oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, 69.2 x 87.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

The wrath of God

Albert Pinkham Ryder’s seascapes are, if anything, even more intense images of the turbulent violence of the sea. For Ryder, though, the natural world is more clearly presented as a tool of divine retribution. His illustration of the story of Jonah is a tumultuous image, mixing biblical and literary imagery with a depiction of the natural world in order to create a terrifying scene.

The biblical Book of Jonah tells the story of a man chosen by the Jewish God to preach on distant shores. He is afraid, and so attempts to flee from this task, and from an omniscient and omnipotent — that is, all-knowing and all-powerful — god, by stealing away in the hold of a ship:

Then the Lord sent a great wind on the sea, and such a violent storm arose that the ship threatened to break up. All the sailors were afraid … But Jonah had gone below deck, where he lay down and fell into a deep sleep … So they asked him, “Tell us, who is responsible for making all this trouble for us? … What have you done?” … The sea was getting rougher and rougher. So they asked him, “What should we do to you to make the sea calm down for us?” “Pick me up and throw me into the sea,” he replied, “and it will become calm. I know that it is my fault that this great storm has come upon you.” … Then they took Jonah and threw him overboard. … Now the Lord provided a huge fish to swallow Jonah, and Jonah was in the belly of the fish three days and three nights.Jonah 1:4-1:17.

Ryder might have given us the calm sea after the great fish has swallowed Jonah, but instead he presents the moment of highest drama and chaos. The image has no straight lines, nor any that are horizontal or vertical. Everything is churning and tossing at angles. The sea, here, is as animate a force as the fish, curving toward Jonah from the right edge of the painting. The boat in the center is much smaller than that described in the Bible, since this one has no deck, and one could not retire below it. It is a little boat, not a substantial ship, and this makes the lives of those in it seem all the more imperiled. The form of the boat, apparently on the verge of capsizing, recalls the form of the whale to the right, as they are the only solid, black shapes in the composition. By bending the hull so dramatically, Ryder has animated the boat, as well, transforming it into a gaping maw, ready to swallow those within it.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow, c. 1880-85, oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, 30.4 x 30.4 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

There is more, though: The figure in the background is often taken to be God, pursuing Jonah across the sea, but this does not quite fit. The bearded figure bears wings, which are not part of the iconography (the visual symbols) of the Jewish God. They do, though, suit a figure described in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (first published anonymously in 1798), a poem that directly inspired another of Ryder’s paintings, With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow.

Here, we read

And now the Storm-Blast came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with o’ertaking wings,

And chased us south along.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1798, lines 41-44.

The visual elements of With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow serve to highlight those of Jonah. The earlier painting, while also showing a small boat on a dark sea, has a strong horizontal line for the horizon. The waves do toss the light boat about, but the figures do not seem as desperately endangered. Returning to Jonah, we might view the massive, winged figure who seems to be driving the storm as “the Storm-Blast … with o’ertaking wings.” If so, even the storm itself is an animate element in this turbulent image. In Sesshu’s painting, the cold winter seems impersonal, but for Ryder, the storm — sent by God — is quite personal, seeking out Jonah in the hold of the ship. The great fish is also merely a tool of God, not a normal element of the natural world.

In the grip of a storm

The power of storms is a popular theme in art. We might also look, for example, to the work of Rafael Tufiño, one of the founding members of the influential nationalist Centre of Puerto Rican Art. His Temporal (Storm) is a print based on a popular song about the San Felipe hurricane that inflicted great damage to his native Puerto Rico in 1927.

Here, as in the Ryder, the power of the wind is again personified, now into a massive, dark giant looking over the helpless people below him. Men, women, and children, even a naked baby, are all swept up into the storm. The lines convey the great, swirling motion of the hurricane, and the bodies within it seem passive, as inert as rag-dolls. A moment of high contrast in the print draws our attention to the figure with his arms raised, caught in the grip of the storm. The cluttered town to the lower right is also being swept away by the wind, seemingly under the direction of the giant’s extended left hand.

In some cases, granting intention and will to the natural world is not merely a metaphor, as it is for Tufiño, who did not really think that the hurricane was a malevolent giant, or Sesshu Toyo, who used it to convey the idea of all worldly suffering. In the figure of Zeus, the power of lightning is literally embodied in the powerful, muscular body of the god, and his intentions guide its direction. Still, the impersonal quality of natural violence is reflected in his impassive expression.

Love and sensuality

Where Sesshu Toyo, the muralist at Çatalhöyük, Turner, Ryder, and Tufiño all emphasized the harshness and danger of the natural world, Jean-Antoine Watteau instead gives is a romantic scene of joyous frolicking in the great outdoors. His painting Pilgrimage to the Island of Cythera depicts a group passing through a lush landscape. The patrons for works like this were wealthy city-dwellers, largely removed from the dangers presented by the natural world.

Watteau was an innovative painter who began his career by rapidly churning out quick copies of religious paintings and then turned to comic scenes before finally inventing this sort of scene, known as a fête galante — an image of elegant outdoor entertainment. It conveys a frivolous atmosphere of aristocratic ease. The soft, gossamer brushstrokes suggest that these figures (and the patrons of the work) were not often exposed to the rigors of the natural world, and did not wish to be reminded of them.

Here, the beautifully dressed couples, accompanied by putti (the winged cupids floating about) are either heading to or from the mythical island of the goddess Venus, and therefore the island of love. Their casual, communal stroll is in strong contrast to the uphill struggle of the lone figure of Sesshu’s Winter Landscape. Indeed, everything here is quite at odds with Sesshu’s harsh presentation of nature.

If we follow the procession from left to right, we see that, accompanied by floating cupids symbolizing erotic love, the figures are already pairing off into romantic couples in increasingly compromising positions. At the end of the procession is a statue of Venus, wrapped in a garland of flowers.

The rich abundance of nature here echoes the figures’ sensuality. This springtime scene is bursting with life, unlike Sesshu’s hard winter. Where his trees were bare, these erupt in rich greens. Where his lines were crisp and sharp, Watteau’s are soft and blurred. Where his palette was paired down to shades of grey, Watteau’s relies on the springtime pastel tones. The complete ease and safety of these figures is suggested by their spotless clothing. They are richly attired in pale silk, not marred by a speck of dirt or smear of grass. These cheerful figures pass through the landscape without being soiled by it.

Three couples (detail), Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera, 1717, oil on canvas, 4’3″ x 6′ 4 1/2″ (Louvre, Paris)

It is, though, also possible to read this as a somewhat melancholy image of the departure from the island of love. The poses of the figures are ambiguous. For example, is the middle couple of the three in the foreground in the process of sitting down or standing up? The image presents a dream world, but a fleeting one that may already be passing. If we follow the flow of the figures, guided primarily by Watteau’s use of value, we begin with the figures closest to us, drawn in by the woman’s bright white gown and pink robes. We then follow the brighter tones down and away and then up, as the putti seem to drift off and away, perhaps carrying our prospects for love with them.