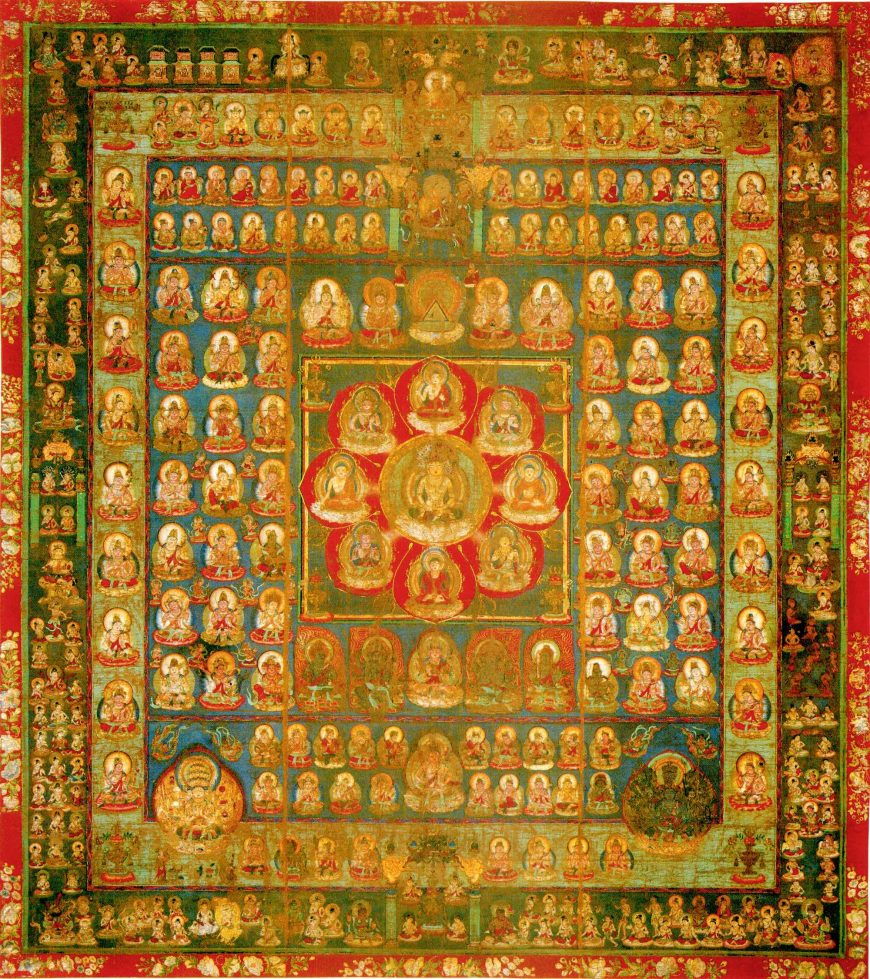

Garbhadhatu (Taizokai) Mandala (Womb World), mandala of Innate Reason and Original Enlightenment, Japan, Heian period (Tantric Buddhism), late 9th century, colors on silk

When an image or object is repeated throughout a work of art, or a part of a work, this is called either pattern or repetition.

Repetition and pattern

Repetition can be less structured than pattern, which is more regular. Both can work to create a sense of rhythm, as discussed below. The large base of a Ming Dynasty Chinese Bronze statue of Vairochana Buddha is composed of literally thousands of tiny bodhisattvas (Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have chosen to stay on earth to help others achieve enlightenment), which therefore seem to serve to support Buddha figuratively, as well as visually. Their repetition is very regular, establishing a clear pattern. This is also the case in the Buddhist mandala from the 9th century. The pattern in both cases emphasizes the unity of purpose shared by these thousands of figures, each an embodiment of the ideal of compassion.

Rhythm

Rhythm is the visual tempo set by repeating elements in a work of art or architecture. The arches and columns of the Great Mosque of Cordoba provide a good example. They are spaced very evenly, setting up an even tone to the building. This is then enlivened by the rhythm created by the striped pattern on the arches.

Hypostyle hall, Great Mosque at Cordoba, Spain, begun 786 and enlarged during the 9th and 10th centuries (photo: wsifrancis, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

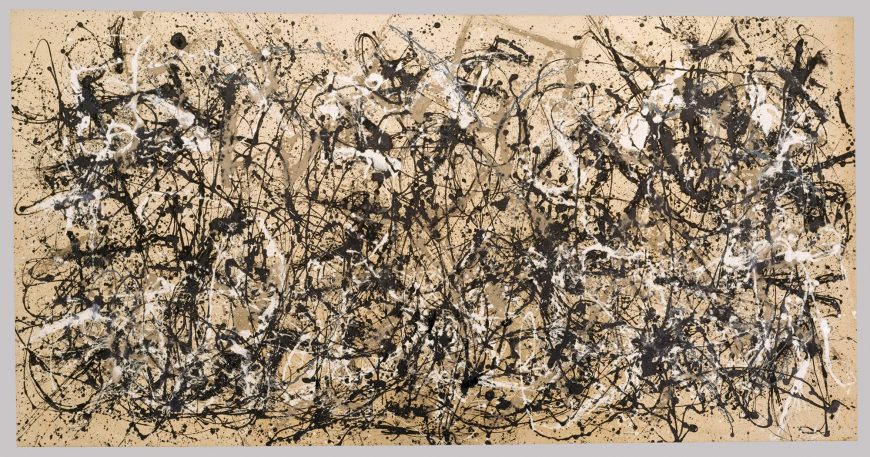

For contrast, we could look at Jackson Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (# 30). Pollock was a fan of jazz music, and tried to capture something of its loose, syncopated rhythms. The resulting drip-paintings (they were made with the large canvases lain on the floor of his studio) have similarly loose, improvisational compositions. Despite its lack of formal structure, there is a clear rhythm running horizontally across the painting, and Pollock uses the title of the work to draw our attention to it.

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950, enamel on canvas, 266.7 x 525.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Detail, Garbhadhatu (Taizokai) Mandala (Womb World), mandala of Innate Reason and Original Enlightenment, Japan, Heian period (Tantric Buddhism), late 9th century, colors on silk

Variety and Unity

Variety is the use of different visual elements throughout a work, whereas unity is a feeling that all the parts of a work fit together well. These do not have to be opposites, as a work filled with variety might also have unity.

The World Womb Mandala is an excellent example. Unlike the Ming Dynasty Bronze statue of Buddha, where all of the bodhisattvas are more or less identical, the many bodhisattvas on the World Womb Mandala are each individualized. At a distance, they all become one, expressing great unity, but taken one at a time, each as an object of devotional contemplation, they contain more variety than it would at first appear.