We again begin with a garden. However, this garden is so vast and rich as to enclose within it many forms of pleasure not generally associated with pleasant strolls in gardens.

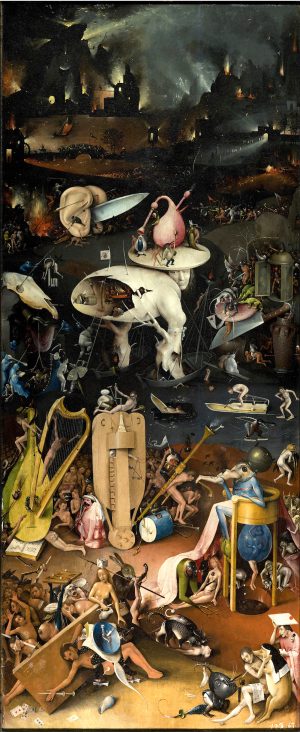

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

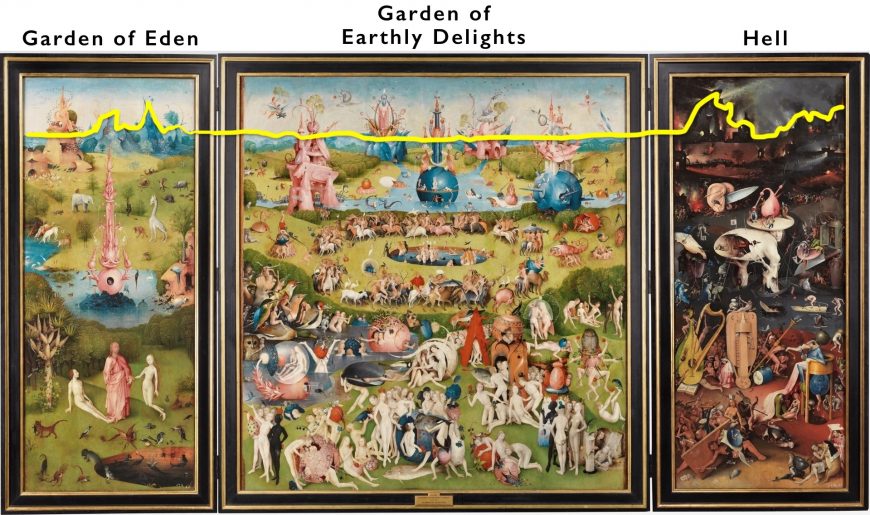

The Garden of Earthy Delights is Hieronymus Bosch’s most famous work, and justly so. It is massive (more than twelve feet wide), riddled with an almost impossible-seeming level of detail, all painted in luminous colors. The work is a triptych — a painting with three panels, hinged together so that the outer panels, or wings, can be closed over the central panel.

Animation of triptych opening to reveal interior view, Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights

Subject

The left wing presents the Garden of Eden—the place in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition where God creates humanity.

The right wing shows Hell—a place of punishment in the afterlife for those who live sinfully.

The subject of the center panel, though, is less clear. This is the Garden of Earthly Delights, a fantasy riot of bizarre imagery, of giant animals, monsters cobbled together out of bits and pieces of other creatures, of all sorts of sexual escapades and gluttonies. What was Bosch saying about these pleasures? How are we to interpret the triptych, as a whole?

The common horizon line (marked in yellow), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

A continuous landscape and birds-eye view

The entire triptych forms a continuous landscape, indicated by the common horizon line. From a distance, the soft greens of the grasses and trees, the gentle blues of the waters and sky, and the points of bright pink punctuating the left and center panels give the impression of a lovely spring day.

The work invites us closer with its seemingly innocent palette and, due to the small scale of the figures, its promise of rich details. However, as we approach the center of this large work — over twelve and a half feet in length — we find the tiny images that fill so much of the composition are rather startling! There are hundreds of figures, almost all of whom are entirely naked. They dance and cavort, embrace and contort; they not only ride but also caress and cuddle fantastic beasts. They grab gluttonously (or lustfully?) for impossibly large fruits and berries. And, above all, they seem to be having a very good time.

The horizon in all three panels is quite high, almost at the top of the image, which gives the viewer a bird’s-eye perspective on the scenes. This elevated perspective gives us a bit of distance from the wild cavorting in the center image, and also from the odd forms of torture in the Hell scene. We are floating above the fray, rather than walking among the hundreds of naked figures.

The left panel: Garden of Eden

God/Jesus with Adam and Eve, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

In the left panel, we see the Garden of Eden, where Adam and Eve are being introduced to one another by a figure that seems to be Jesus (though it would normally be God the Father at this point in the story). Adam reclines calmly on the grass while Eve, framed by the shining gold mandorla of her hair, falls to her knees beside him. The image is roughly symmetrical, with the figure of Jesus/God just to the right of center, beneath a strange fountain that is the same shade of pink as his robes. Again, at a glance, all looks relatively normal. As is typical, Eden is shown as a bountiful land, overflowing with abundance.

Fountain and, to the lower right, a three-headed lizard, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

However, the choice of animals is somewhat peculiar. In addition to the bears, stags, horses, cows, porcupines, boars, and birds, there are many exotic animals: an elephant with a monkey on its back, a giraffe, a unicorn drinking from the lake to the left, and a whole host of unidentifiable fantasy creatures. A three-headed lizard crawls out of the main pond, toward the right edge of the panel, and a three-headed bird hangs over the murky pool in the foreground, perhaps trying to catch the sea-unicorn or spoonbill-fish swimming before it.

While we recognize the giraffe as a real animal, and we consider the two-legged dog in front of it and the rearing dragon just above it as fictitious monsters, early sixteenth-century viewers would have perhaps found them equally fantastic — or equally real. They would most likely not have seen any African or Asian animals in person, and would only have seen them or read about them in the same sources where they would have read about dragons and unicorns.

Trouble in Paradise

A lion is devouring a deer or antelope and a cat with a creature in its mouth (details), Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

While Eden is often depicted as a peaceful place where “the wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together” (Isaiah 11:6), in Bosch’s Garden, in the upper right, a lion is devouring a deer or antelope. As if balancing this, to the lower left, a cat has caught a dark, unidentifiable creature, perhaps a rat, perhaps a lizard, perhaps both.

The cheerful palette, calm, symmetrical composition, and careful, linear forms all belie the troubling nature of the details throughout the image.

Hieronymus Bosch, Detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm

The central panel

The central Garden panel is divided into three sections (see left), foreground, middle ground and background. The foreground contains the greatest level of detail.

The pond to the left contains some of the most remarkable of vignettes, including a couple embracing within what seems to be a giant bubble of a berry.

The shine of light off of the surface of the bubble is rendered with great care, partially obscuring our view of whatever is happening within.

To the left, a man embraces a giant owl, while above them men and women ride a wonderfully detailed group of birds, all recognizable as specific species, such as the mallard duck, kingfisher, and hoopoe, with its great beige crest.

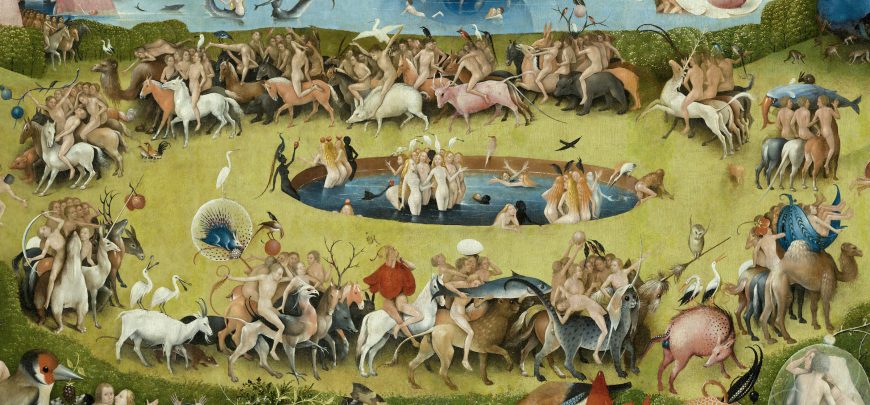

Pool of the Maidens

Pool of the maidens, central panel, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

The focal point of the entire triptych (in so far as this dizzying composition has one), is the so-called Pool of the Maidens. It is just above center, aligned on the vertical axis of the center panel and therefore of the entire work. Here, a group of naked young women swim and cavort. Some bear apples on their heads and one, toward the center of the pool, bends forward and balances an apple at the base of her spine, where she seems to also have a fish tail.

Several of the women seem to gaze outward, and if we follow the implied lines of their gazes and gestures, we realize that they are looking at the wild procession that surrounds them. Naked men ride a fabulous menagerie of animals — horses, camels, and cows, but also a griffin, a lion, and a unicorn-cat, among many others. Perhaps all of the couples and groups throughout the painting began at this pool before pairing up and finding semi-secluded nooks in which to embrace — a giant lobster tail, the shell of a giant mussel, the interior of a giant fruit, and so on.

Right panel, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

Right panel

This leaves the right panel; here, everything changes except, importantly, the continuous horizon line. The colors are much darker, with all the tints of the Gardens of Eden and Earthly Delights giving way to the dusky shades of Hell. The rich, verdant fields are replaced with hard, bare earth. The warm and inviting blue pools are replaced with a grey and black lake of ice. The strange pink and blue architecture, populated with animals, birds, and seemingly joyful people are replaced with jagged buildings that seem to be at once in the process of being built and of burning down. The light that blasts out of their windows and doors illuminates a sky choked with smoke, in contrast with the fresh blue skies of the Gardens. It is important, though, that the horizon line carries over, to remind us that these highly disparate scenes are directly and intimately connected.

It’s about scale

Throughout all the panels, scale is vital. These are all large panels, over seven feet tall, but the figures are quite small. Bosch’s sustained creativity is astonishing; he created a painting with hundreds of figures, each of which is entertaining, curious, or downright bizarre. This is a work that rewards very close looking, and invites our gaze to linger at great length over its detailed and fascinating surface.

Bosch listed as a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood, c. 1742 (Brabants Historisch Informatie Centrum)

Cultural context: moralizing times

Bosch lived in highly moralizing times, in a culture that condemned most or all bodily pleasures as sinful. He married a wealthy woman twenty-five years older than he was, and lived in her large estate. He was among the wealthiest residents of the town (s-Hertogenbosch), and did not need any income from his painting.

He was a member of a religious confraternity called the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, dedicated to the worship of the Virgin Mary, and not only completed five paintings for the group but was also the only artist to be a member of a group that otherwise consisted of Christian clergy and scholars, suggesting both his strong dedication to the group, and their approval of his work.

How do we reconcile this with a painting like the Garden of Earthly Delights, which depicts such a seemingly free series of pleasures?

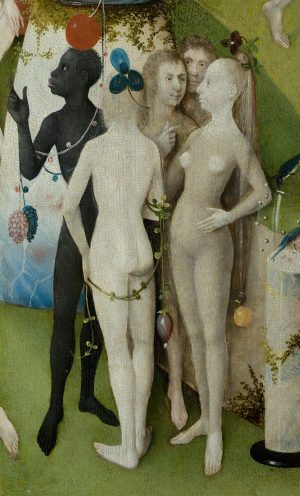

African figures, Moors and “wild women”

Figures in the foreground, central panel, Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, triptych, oil on panel, 220 x 390 cm (Museo del Prado)

It is worth noting that there are several African figures in the pool and throughout the image. In the early sixteenth century, there would not have been many African people in the Netherlands, and it is to be expected that the vast majority of the figures are pale-skinned and light-haired. What are these figures, like the one that poses with a cherry on his head at the lower right, doing here? It seems likely that they are part of the effort to represent an “exotic” scene, to include the variety within humanity just as Bosch has included the variety within the animal kingdom.

There are also bluish grey figures that may be intended to represent Moors—North-African and Spanish Muslims, who are often depicted in similar shades. There are even a few hirsute figures — figures whose whole bodies are covered with hair or fur, such as the woman standing in the same cluster as the African figure with the cherry on his head. Her body is entirely covered in glistening, golden hair, except for her face, hands and feet — and, notably, her breasts. She and the other figures like her may be “wild women,” a popular subject of the period, standing in for the freedoms represented by the forest, idealized as untainted by the culture of the city, living in a state something like that of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.

Compared with the Last Judgment

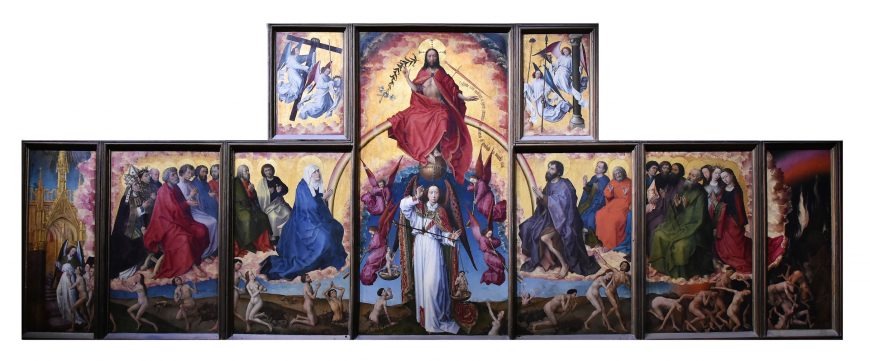

The pleasures of the Garden are clearly not only sexual, but more broadly sensual. Some figures are engaging in sexual behavior, but others are eating impossible foods and many seem to simply be dancing and delighting in their apparent physical freedom. We must not forget, though, that in the right panel, the Hell scene is tied to the Gardens by the horizon line. This triptych is in many ways similar to common images of the Last Judgment, such as Rogier van der Weyden’s The Last Judgment from 1443-1451, but there is a vital difference.

Rogier van der Weyden, The Last Judgment, 1445-1450, altarpiece, interior view (Hôtel-Dieu de Beaune, image: Wikimedia Commons). Heaven is on the far left, the weighing of souls in the center, and hell is on the far right.

Last Judgments (like van der Weyden’s painting), generally present Hell at the right and the Judgment of the souls in the center (with many small, naked figures moving across the landscape) but to the left, they feature Heaven — not the Garden of Eden. This distinction is critical. Last Judgments present the moment in Christian tradition when Jesus judges all the souls of the dead at the end of time, sending some to Heaven and some to Hell, as we see in the van der Weyden.

Bosch substitutes the Garden of Eden for Heaven (and does the same in his own Last Judgment triptych). This alters the dynamic by adding in the element of time. In the Bible, the human story begins in the Garden of Eden. Therefore, this cannot be a scene balancing the Hell panel, as an image of Heaven would be. Instead, it turns the entire panel into a narrative, a story that moves, as we read, from left to right. For Bosch, humanity begins in the Garden of Eden, which already bears signs of corruption, moves through the Garden of Earthly Delights, which seems to be his representation of his own world, and therefore ends — inevitably and for all people, in Hell. The joyous pleasures of the Garden are clear, richly invented and depicted in great detail, but for Bosch, they bear strong consequences.

Condemning sensuality but pleasurable to contemplate

While the Garden of Earthly Delights is, as a whole, a strong condemnation of sensual pleasures, the work is nonetheless unquestionably pleasurable to contemplate. Its shocking variety and ingenuity gives the viewer cause to dally at length before it, seeking out more and more oddities, more ingenious hybrids, more unusual sexual unions.

Was Bosch unaware that his masterpiece was, in a sense, working against its very goals, providing the viewer with seemingly endless diversion? Or was he perhaps instead mocking his viewers, tricking them into engaging in a range of pleasurable sins at the same moment that he was instructing them that such sins led to the fires of Hell?

In his rich, visionary images, Bosch presents scenes of pleasure and inspires pleasure in his viewers, but also undercuts that pleasure by arguing that it bears dire consequences.