Tracey Emin, My Bed, 1998 (Tate Britain)

A Young British Artist

In 1998 the British artist Tracey Emin spent several days languishing in bed as the result of depression. When she emerged, she decided to turn the experience into art and the result was My Bed, an installation that consisted of her unmade bed and an assortment of sundry personal items associated with her time spent there. This was not the first time Emin made art about things that many would consider excruciatingly personal. She once exhibited, as art, a package of cigarettes belonging to an uncle killed in a car crash. In 1997, she created an installation entitled Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995, which was a tent appliquéd with the requisite names. Parts of My Bed were so shocking—it included soiled underwear for example—that she became a tabloid sensation.

Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963 – 1995, 1995, appliquéd tent, mattress and light, 122 x 245 x 214 cm (Saatchi Gallery)

Emin was part of a group of artists who had studied at Goldsmith College and Royal College of Art in London and were dubbed the YBAs (Young British Artists). Members of this ad hoc group, including Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Liam Gillick, and Gary Hume among others, very quickly coalesced into a movement, and began exhibiting together in warehouses and other informal spaces during the late 1980s. Hirst had organized the exhibition Freeze, widely acknowledged to have been the movement’s origin, at an abandoned space in the London Docklands in 1988.

Damien Hirst, Mother and Child (Divided), exhibition copy 2007 (original 1993), glass, stainless steel, Perspex, acrylic paint, cow, calf and formaldehyde solution, 2 parts: 208.6 × 322.5 × 109.2 cm, 208.6 × 322.5 × 109.2 cm (Tate Britain)

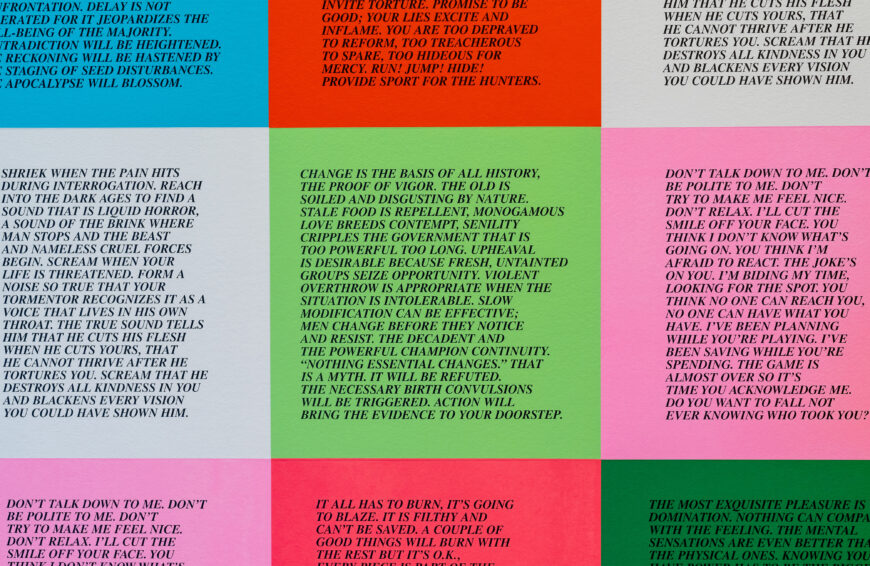

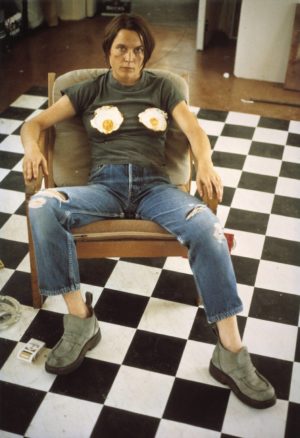

Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996, digital print on paper, 74.5 x 51.4 cm (Tate Britain)

YBA works quickly became associated with sensationalism and shock value, the impact of which was only heightened by the prevailing decade of postmodern art which, to a younger generation of artists, had increasingly become depersonalized and too reliant upon a dense theoretical framework. I remember an art school at the time in Canada issuing a call for work for a student exhibition with a list of caveats including “No hand wringing over the relationship between signifier and signified” (a reference to semiotic theory popular at the time). Everywhere it seemed a reaction to slick postmodernism was to be found in a return to a less technologically-mediated reality. The more visceral the better. Well-known YBA artworks include a calf suspended in formaldehyde (Damien Hirst), a sculpture of two fried eggs and a kebab arranged in the shape of a female body (Sarah Lucas) and of course Emin’s My Bed, which scandalized a British public with its frank portrayal of the detritus of four days of depression spent in bed.

Shock value

Shock is of course not new in art; the art-going public have been routinely scandalized at least as far back as the nineteenth century, when artists first went against accepted norms for what constitutes art. The significance of Emin’s installation, however, lies beyond its shock value. After all, shock is generally a short-lived phenomenon. Emin went on to become a nominee in 1999 for the Turner Prize, a prestigious visual arts award given annually in Britain. So what makes My Bed important as an artwork? Emin subjects to scrutiny one of the most abiding beliefs of art in Western modernism—the notion that art is always autobiographical, a reflection of the artist’s inner being.

As Western art increasingly became governed by more individualistic approaches to style and as religious and royal patronage gave way to the marketplace in the nineteenth century, the association of art with individual identity became an accepted norm. “Every painter paints himself” is a phrase known since the renaissance and it is a metaphor of this very idea that art is always an expression of the self at its core. But what does it actually mean? What aspect of self is expressed? When pressed, one is hard put to offer anything other than the most generic response: it represents emotions or feelings and perhaps a sensibility. What Emin does is take the meaning of self at its most literal sense and in the most provocative way possible. She does however present a portrait of the melancholic artist that references a tradition stretching as far back as the German renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 engraving Melencolia I, an allegorical winged female figure in a state of pensive gloom considered to be a portrait of the artist himself. But Emin’s is an unvarnished and unidealized version of depression in which glorified myths of the artist are shed in favor of a frankly visceral portrait of an artist who has spent her days in bed drinking and having sex. Emin perverts that tradition and therein lies its challenge to conventional taste.

A new conceptual art

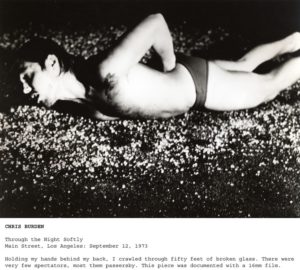

Chris Burden, Through the Night Softly, 1973, performance (Gagosian)

In the 1990s, as artists searched for new alternatives, many considered conceptual art of the 1970s an unfinished project. While rooted in conceptual art, postmodernism’s focus on media spectacle and consumer objects had become too tied to a market-oriented idea of the art world. Artists began revisiting the strategies of earlier artists, particularly the more visceral bodily experience that was an important aspect of conceptual art. The unflinching realness of Emin’s bed would not have been possible in the postmodern ‘80s but it certainly existed in the 1970s when artists like Chris Burden crawled through broken glass (Through the Night Softly, 1973), or had himself nailed to the front of a car (Trans-fixed, 1974).

Vito Acconci, Claim Performance, 1971, graphite, pastel and black & white photograph collage mounted on board, 58 x 71 cm

From 1968 to 1971 Valie Export toured European cities with a structure made of styrofoam that allowed people to reach inside it and touch her breasts. The artist Vito Acconci had himself blindfolded in the basement of a gallery, and armed with metal pipes and a crowbar, would threaten to swing at anyone who came near (Claim, 1971). Challenging conventional ideas around artistic creativity, as these artists did, is, in fact, a venerable tradition in modern and contemporary art. Artists continually renew the conditions and parameters of what constitutes art or artistic authorship.

Much like conceptual artists who rejected the medium of painting as too conventional in favor of newer and more experimental forms and ideas, Emin had abandoned painting and even went so far as to destroy many of them. In a famous argument with artist and boyfriend Billy Childish, she referred to his paintings as “stuck” in time. In response, Childish formed a movement called “Stuckism” which promoted painting and creative expression while denouncing Emin’s brand of conceptual art. “Stuckism” would prove to be short-lived, but Emin’s My Bed would become one of the most resonant works of the 1990s.