A 15th-century Florentine painting tells us about the arrival of oil painting to the city, international trade, and slavery in the renaissance.

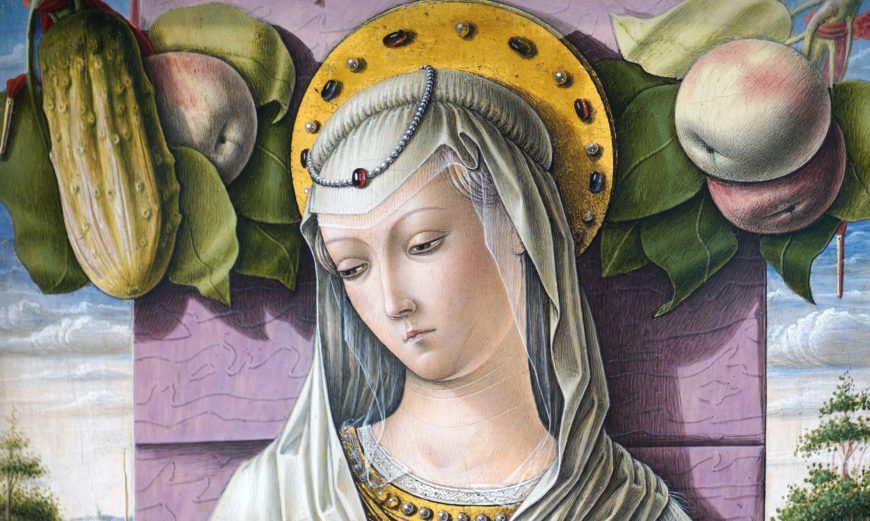

Filippino Lippi, Madonna and Child, c. 1483–84, tempera, oil, and gold on wood, 81.3 x 59.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), an Expanding Renaissance Initiative video. Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re in the galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, looking at a Renaissance painting by Filippino Lippi of the Madonna and Child that was likely commissioned by one of the wealthiest families in Florence, the Strozzi family.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:20] This is a typical Madonna and Child scene. It was very common at the time. We see Mary tenderly holding Jesus as a baby, and he is very playfully turning the pages of a book. Lippi has painted him to look like an actual child, with all the naturalistic baby fat and rolls.

Dr. Harris: [0:40] Mary, too, looks like a human mother. She looks down at her child. Although there is that sadness on her face that we frequently see in images of Mary holding the Christ Child, because there’s this idea that Mary has a foreboding, a sense of the tragedy that will come.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:56] They’re seated inside a Florentine palace. There’s a window behind them that looks out onto a cityscape, and then beyond that, we see it receding into this larger, hilly landscape.

Dr. Harris: [1:09] Art historians think that the building that we’re seeing outside may be the Strozzi villa that was located outside of Florence.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:15] There’s evidence for this in the painting as well. If we look at the top left, we see a portion of the armorial device for the Strozzi family, and it was three crescent moons, of which we’re seeing two in the painting.

Dr. Harris: [1:27] To me, this painting has everything that I expect of the Renaissance. It has figures who are naturalistic, who are three-dimensional. Lippi is using modeling to make the figures have volume and take up space. There’s a consideration for the human body, for human anatomy, which is especially evident in the figure of the Christ Child, who’s nude.

[1:48] But there’s also this love of the material world, the blue fabric that feels like heavy blue woolen or velvety fabric, the translucency of the fabric that she wears around her head, the velvet of the cushion that the book leans on, the carved wood, the brass candlestick, this embracing of the material world in a spiritual image.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:11] Part of that interest in textures, in depicting these luxury materials in such a naturalistic way, is actually a result of something that’s happening in Florence right at the time that Lippi is painting. This painting dates to around 1483, 1484. Just prior to this painting, you have the introduction of oil painting into Florence.

[2:31] You have the “Portinari Altarpiece” that has come with Tommaso Portinari, a Florentine banker who was in northern Europe, and he becomes very interested in Flemish painting, where you have oil painting that’s developed. He brings this “Portinari Altarpiece,” the first oil painting really to arrive in Florence, and it’s a huge sensation.

[2:52] Artists like Lippi are drawn to it and they begin to adapt oil painting into their technique.

Dr. Harris: [2:59] You can see why Lippi wanted to paint with oils, not only the depth of the color, saturation of the color, but the way he’s able to render the texture of different objects — for example, that velvet of the cushion or the reflections on the brass candlestick in the background, or even Christ’s hair, which we can see in little wisps.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:20] It really is a masterful pairing of the sacred and the secular, where we have Mary placed into a contemporary Florentine palace with a contemporary Florentine landscape in the background.

Dr. Harris: [3:32] Also that blue of the cloak that she wears comes from a semi-precious stone, so it’s especially valuable.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:39] The blue of her mantle is ultramarine, which derives from lapis lazuli, which comes from mines in Afghanistan, and it could only be mined about six months of the year.

[3:49] At this time in the late 15th century, lapis lazuli was more expensive than gold. It was an extremely precious material and not everyone could afford it, but people like the Strozzis could afford it, and they really wanted to put on display this material splendor.

Dr. Harris: [4:05] What’s especially interesting about this painting, too, is the view out the window and specifically what we see there.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:11] The cityscape and the landscape that we see through the window is indebted to these Flemish paintings and painters, where you often see rooms, then a window outside where you can get this deeper recession into the landscape.

Dr. Harris: [4:24] We could think of paintings by artists like Rogier van der Weyden, where you have a spiritual scene, but a view out the window of a contemporary landscape going deep into the distance, but where the artist has paid a lot of attention to it, so that even though it’s far in the distance, there’s quite a lot to see, and that’s what we have here.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:41] We’re seeing two peasants that are crossing a bridge, carrying what look like agricultural tools. We see a woman in the middle ground wearing this bright red dress, so our eye is drawn to her, and she’s pouring water into a pitcher. Further in the background, we see two men who are spearfishing.

[4:59] Three of the five figures that you see in the background are Black Africans. This painting tells us a lot about what’s happening in this moment in terms of slavery.

Dr. Harris: [5:09] The Portuguese were engaging in the slave trade in West Africa, bringing slaves back to Europe.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:16] The Ottomans, who had taken over Constantinople in 1453, disrupted the flow of slaves from the Eastern Mediterranean, and so with the Portuguese exploration of Western Africa, they begin to trade for things; not only objects, but also people.

[5:35] Women in particular were more desirable. The figure in the red dress in the background is an enslaved Black African woman.

Dr. Harris: [5:42] We can assume that the two Africans who are fishing in the background are also enslaved.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:48] It was likely that there were many different enslaved Sub-Saharan Africans here in places like Florence. Filippo Strozzi freed one of his African slaves at his death as a way of trying to atone for one’s sins, the sin of slavery.

Dr. Harris: [6:02] So if you freed your slave, perhaps you had a better chance of getting into heaven.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [6:06] This painting is really important, not only because it shows us a very typical scene of the Madonna and Child in a very sumptuous way, using lavish materials, but it reveals to us that there were many different types of people living in Renaissance Florence, even though we tend to forget that it’s a much more dynamic and complicated place than we usually think of.

[6:27] [music]