Unknown Japanese painter, St. Francis Xavier, late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries, Japanese watercolors on paper, 61 x 48.7 cm (Kobe City Museum)

A Discovery in Takatsuki

In 1920, researchers from the Kyoto Imperial University in Japan made a miraculous discovery. They found a locked chest—seemingly unopened for centuries—tied to a beam in the ceiling of an old house. When they opened it, they discovered a small collection of Christian artworks and texts. These were rare survivors from the European missions that sought to convert the Japanese people (who traditionally practiced Shinto and Buddhism) to Catholicism. This effort dramatically came to an end in 1614 when the Tokugawa government outlawed Christianity and expelled all European missionaries.

The two paintings in the chest—likely created by unknown Japanese-Christian artists—depicted the Fifteen Mysteries of the Rosary and St. Francis Xavier, the first Catholic missionary in Japan and a member of the Society of Jesus. Unfortunately, the box contained no documentary records that could tell us when this image of Francis Xavier was created, where or who it was made for, or how it was used. Although many of the basic facts about the painting remain the subject of debate, it is clear that the painting is an invaluable record of cultural, religious, and artistic interaction between Europe and Japan in the early modern period.

The Failed Mission to Japan

In July 1549, Francis Xavier arrived in Japan, hoping to find success converting the Japanese to Christianity. Xavier initially struggled due to his lack of knowledge of the Japanese language and his inaccurate understanding of Japanese Buddhism. Still, he laid the foundation for a successful mission that continued to grow after he left Japan to return to India two years later. Scholars have estimated that more than 300,000 people in Japan converted to Christianity over the next fifty years. However, this brief Christian experiment ended in 1614 when the Tokugawa government outlawed the religion, beginning a period of persecution that resulted in the torture and execution of more than a thousand Japanese Christians and European missionaries. At this time, all Christian churches that had been built in Japan were destroyed, along with the works of art that had decorated them.

Maria-Kannon, Dehua porcelain from Fujian Province, China, imported to Japan for Christian veneration (Nantoyōsō Collection, Japan; photo: Iwanafish)

A sizeable portion of these Christians managed to continue to practice their faith despite the constant danger of detection by government officials. Christian works of art played an important role in helping them maintain their devotional practices, and create a sense of religious community and identity. For example, statues of the bodhisattva Kannon in a feminine form holding a child (such as the one above) appeared Buddhist on the surface, but due to similarities in iconography, could be regarded as images of the Virgin and Child by secret Christians. Devotional images with obvious Christian iconography that had no Buddhist counterpart, such as the Kobe painting of St. Francis Xavier, were more dangerous. In many cases, they had to be hidden away.

Satis est, Domine, satis est

Left: Unknown Japanese painter, St. Francis Xavier, late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries, Japanese watercolors on paper, 61 x 48.7 cm (Kobe City Museum); right: Hieronymus Wierix, St. Francis Xavier, 1596, engraving, 84 mm x 61 mm (Rijksmuseum)

The Kobe painting of St. Francis Xavier is undeniably a product of both Japanese and European visual culture. The materials are Japanese, but the artist demonstrates some familiarity with European pictorial techniques like modeling in light and shade. The artist has also based the composition on prints of Xavier, such as those by Flemish printmakers Theodoor Galle and Hieronymus Wierix. European prints were sent to overseas missions to instruct converts in their new faith and also served as source material for non-European artists. They were a common means by which artistic knowledge circulated throughout the early modern world.

Unknown Japanese painter, St. Francis Xavier, detail, late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries, Japanese watercolors on paper, 61 x 48.7 cm (Kobe City Museum)

The Kobe painting of Xavier follows the basic format of the Wierix and Galle prints by depicting the saint from the waist up in a three-quarter pose. His physical appearance is consistent with textual descriptions written by those who knew him in life. These accounts stress his light complexion, beard, dark hair, and eyes always uplifted towards heaven. In his left hand, he holds a flaming heart from which a crucifix emerges. In the upper right portion of the painting, the background, a neutral dark blue field in most of the painting, transforms into dark clouds that part to reveal a golden aura that surrounds the crucifix.

Emerging from Xavier’s mouth is the Latin phrase “Satis est, Domine, satis est,” meaning “It is enough, O Lord, it is enough.” Many sources record that Xavier, when he thought no one was observing him, would open his cassock to try to cool his burning heart and would utter this phrase, marveling at the generous consolations God had sent him.

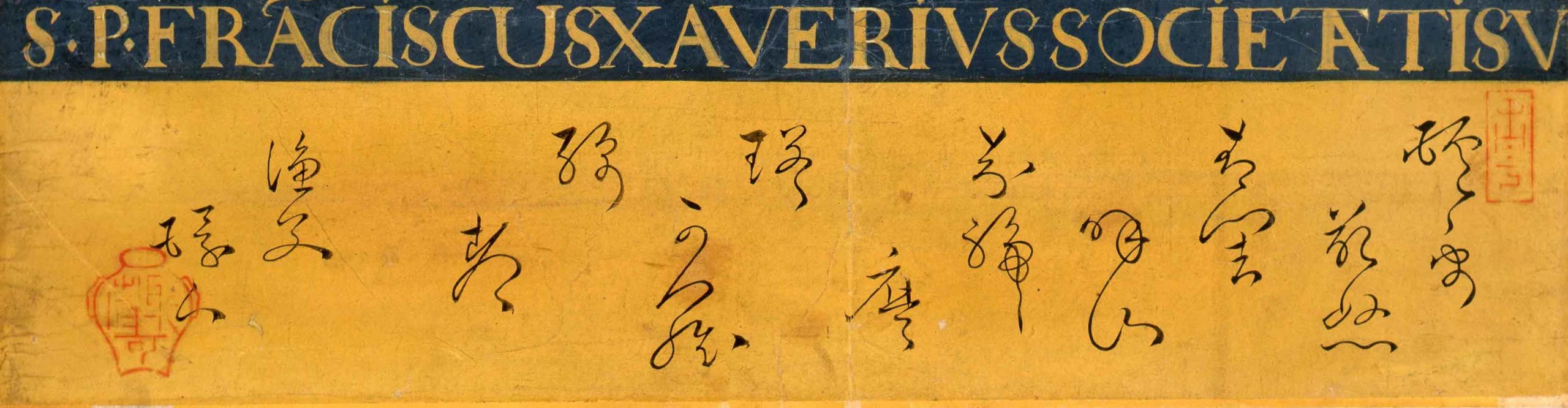

Below the image of Xavier is an inscription in Latin identifying him as a saint and a member of the Society of Jesus. His name is repeated once more, in the bottom-most portion of the painting, where Chinese characters are used to write out the words “St. Francis Xavier Sacrament” phonetically. The painting is also signed “Gyofu Kanjin,” a confusing signature that is not really a name, but instead translates to “fisherman.”

Unknown Japanese painter, St. Francis Xavier, detail, late sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries, Japanese watercolors on paper, 61 x 48.7 cm (Kobe City Museum)

The only other clue to the artist’s identity is a red seal in the lower left portion of the painting, shaped like a pot. This is the seal of the Kanō school, a painting workshop that dominated the artistic scene of the Tokugawa period. One scholar has hypothesized that the Kobe portrait of Francis Xavier was painted by a Japanese artist who had initially trained with the Kanō, but then converted to Christianity and became a priest. This might explain the signature on the portrait, which refers to the artist as a “fisherman” perhaps meaning a “fisher of men.” [1] For the time being, however, this remains speculation.

Japanese Devotion to St. Francis Xavier

Early modern Japanese Christians were especially devoted to Xavier since he had been the first Catholic missionary to bring knowledge of the Gospel to Japan and had supposedly worked several miracles in the Japanese islands. One of the most prominent Xavierian devotees was Ōtomo Yoshishige, a sixteenth-century daimyo who, after his baptism, had taken the Christian name Francisco in honor of Xavier. In 1585, he wrote a letter to Rome asking that Xavier be canonized, so that Japanese Christians could build churches dedicated to Xavier, set up images depicting him on altars, celebrate his Mass, and pray to him for intercession. We know nothing about where the Kobe painting of Xavier was originally displayed, but if it was painted before the prohibition against Christianity, it is possible that it would have been put up in a church on an altar. One scholar has proposed that it was publicly displayed in the Jesuit church in Kyoto and later taken to Takatsuki to be concealed after Christianity was prohibited.[2] Like most things related to the Kobe St. Francis painting, this is just an educated guess.

We do have a few scattered mentions of other images of St. Francis Xavier in letters written by the Jesuit missionaries who remained in hiding in Japan after the 1614 prohibition. A 1625 letter written by a Jesuit who managed to evade the authorities mentions that he brought an image of St. Francis Xavier to a group of hidden Christians in Yamaguchi. These brief, but tantalizing, references demonstrate that although its survival was extraordinary, the painting of Francis Xavier itself was not unique. At the time it was created, it was but one example of the vibrant visual and material culture of Japanese Christianity that celebrated Francis Xavier, the “Apostle of Japan” whose mission had inaugurated the Japanese Catholic Church.

Notes

[1] Grace Vlam, “The Portrait of S. Francis Xavier in Kobe,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 42, no. 1 (1979): pp. 48-60.

[2] Vlam, “The Portrait of S. Francis Xavier in Kobe,” pp. 48-60.

Additional Resources

Learn more about the expanding the renaissance initiative.

Read more about the Tokugawa period in Japan on Smarthistory.

Read more about printmakers like Theodoor Galle on Smarthistory.

Read more about the Kobe City Museum in Japan.

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Art on the Jesuit Missions in Asia and Latin America (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999).

Andrew C. Ross, A Vision Betrayed: The Jesuits in Japan and China, 1542–1742 (Maryknoll, NY: Orbic Books, 1994).

Junhyoung Michael Shin, “Avalokiteśvara’s Manifestation as the Virgin Mary: The Jesuit Adaptation and the Visual Conflation in Japanese Catholicism after 1614,” Church History 80, no. 1 (2011): 1–39.

Grace Vlam, “The Portrait of S. Francis Xavier in Kobe,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 42, no. 1 (1979): 48–60.