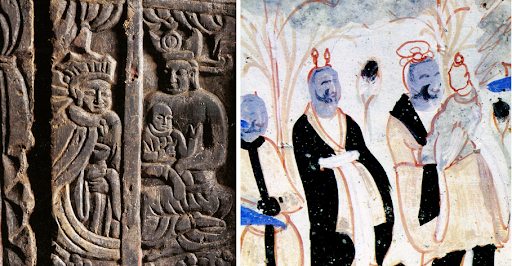

Wirkak or Shi Jun (史君) sarcophagus, 579–80 (Northern Zhou dynasty), stone carvings with traces of pigment and gilding, China, Shaanxi Province (The Xi’an Cultural Relics Conservation and Archaeological Research Institute)

A pictorial biography of a Central Asian couple in 6th-century China

Early in the 6th century, a young merchant travelled along the Silk Road, journeying from his hometown in Central Asia to Northwest China. There he would rise to be a leader in the local Central Asian immigrant community and also started a family with a Central Asian woman. Eventually, at the age of 86, the merchant died, followed by his wife one month later. The place where the couple were buried is located about 2,300 miles away from the merchant’s birthplace, which is more than the distance between New York City and Mexico City.

The couple was Sogdian, an Iranian people who originated in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Since the 4th century, the Sogdian homeland served as a nexus between East and West, and Sogdian merchants traveled widely along the Silk Road. By the 6th century, Sogdian immigrant communities had formed in all major cities along the routes connecting Central Asia and China. (See a multimedia map of the Sogdian trade routes here.)

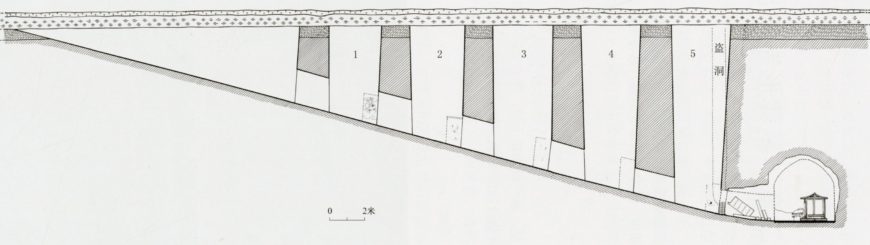

The tomb of this couple was discovered at a construction site in Xi’an in 2003. It consists of an underground chamber accessed by a sloped passageway. Except for the sarcophagus and a stone gate, nothing has been excavated from the tomb chamber. Inside the sarcophagus, however, archaeologists recovered a gold earring, a gold ring, a gilt bronze belt buckle, and an imitation Byzantine gold coin.

Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80 (Northern Zhou dynasty), stone carvings with traces of pigment and gilding, China, Shaanxi Province (Xi’an Museum, Shaanxi, China; photo: Gary Todd)

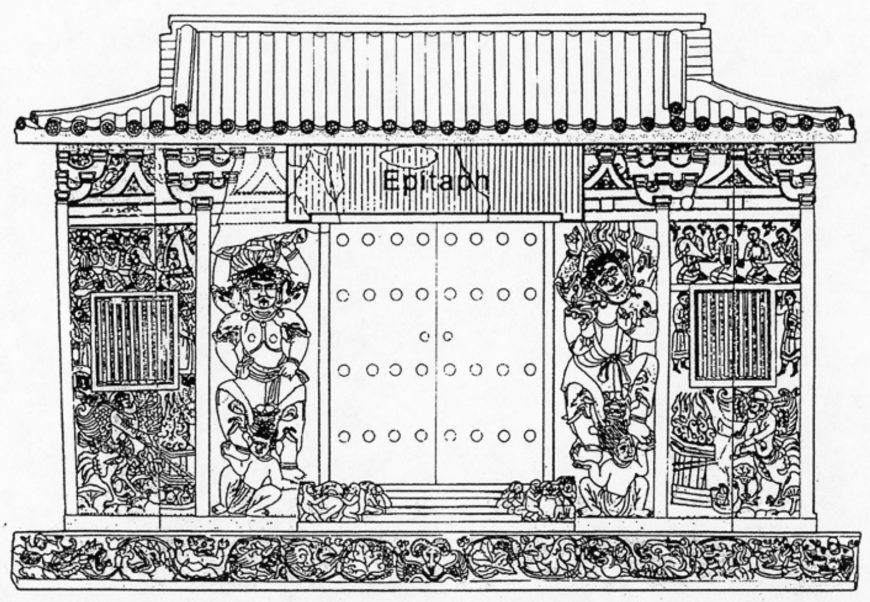

The sarcophagus reflects multiple faiths practiced by the couple and their family. Its shape was intended to recall two types of structures belonging to two different religious traditions—an offering shrine and a stupa. An offering shrine is a native Chinese structure built for worshiping deceased ancestors, and the stupa is a type of Buddhist architecture for accommodating the relics of the Buddha or his followers. Like a stone stupa popular at the time in China, the doors of the sarcophagus are flanked by two ferocious-looking guardians. Besides the guardians, two half-human half-bird figures can be seen attending to fire altars; they are mythical priests in Zoroastrianism (or Mazdeism), a native Sogdian religion.

Bilingual epitaph of Wirkak and Wiyusi (Xi’an Cultural Relics Conservation and Archaeological Research Institute)

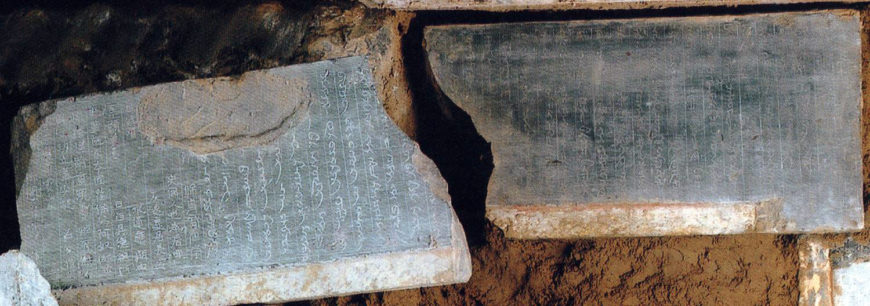

The life of this immigrant couple was recorded in an epitaph written in two languages, Chinese and Sogdian, an Iranian language that was their mother tongue. The epitaph tells us the couple’s names—the merchant was called Shi Jun (史君) in Chinese and Wirkak in Sogdian. His wife was called Kang Shi (康氏) in Chinese or Wiyusi in Sogdian. It also gives us their places of origin in Central Asia (modern Shahrisabz and Samarkand in Uzbekistan respectively), the towns and cities where they lived in China, the dates of their deaths in 579, and the merchant’s official title (sabao 薩保in Chinese). Few migrants’ lives along the ancient Silk Road have been known in such detail.

Unsurprisingly, words were deemed inadequate when it came to commemorating the extraordinary life of the deceased couple. On the surface of the house-shaped sarcophagus built for them, their journey on the Silk Road is illustrated by a succession of vivid scenes. We see: baby Wirkak in the arms of his parents, his hunting as a grown-up accompanied by his caravan, the wedding of Wirkak and Wiyusi, the couple’s embarking on their journey to Central China, and a banquet with friends in their retirement years. Given the short life expectancy of most people in their day, the couple seems to have shared an unusually rich and rewarding life.

Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80 (Northern Zhou dynasty), stone carvings with traces of pigment and gilding, China, Shaanxi Province (Xi’an Museum, Shaanxi, China; photo: Gary Todd)

A story modeled on the life of the Buddha

Even more remarkably, in the eyes of their family and perhaps even in their own, the couple’s lives were not just beautiful, but also blessed, sacred, and even venerable. In fact, their journey on the Silk Road constitutes only one part of the pictorial biography carved on the sarcophagus. There is a broader narrative—one modeled on illustrations of the life of Siddhartha Gautama, the Indian prince who later became the Buddha.

The life of Prince Siddhartha was a legendary journey. Allegedly going through myriad past lives, he was reborn in a royal house around the 5th or 4th centuries B.C.E. Even though he was raised in a magnificent palace, surrounded by all sorts of luxuries, he did not want to be a king as his father had wished. Instead, he embarked on a path that ultimately led to his spiritual awakening—that is, becoming the Buddha. After his death, Buddhism gradually grew to be a universal religion on the Silk Road, spreading from its birthplace at the foot of Himalaya to across Central and East Asia. During the 6th century, the popularity of Buddhism reached a zenith in China and its western regions.

Buddhist temples and caves were among the most prominent sights in cities and natural landscapes, including places like Kucha, Dunhuang, Wuwei, and Xi’an, where Wirkak and Wiyusi lived or traveled. Inside these temples were always illustrations of the life of the Buddha—many of which seem to have been models for scenes on the sarcophagus.

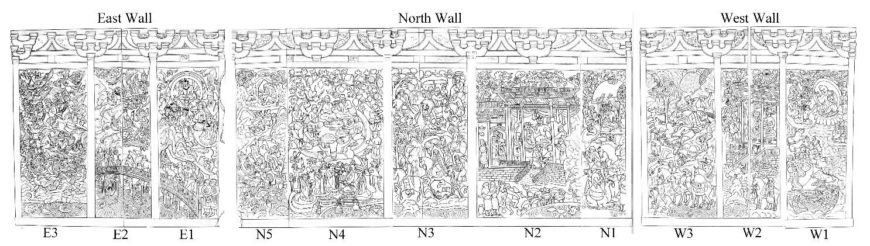

Pictorial biography of Wirkak and Wiyusi on the east (E), north (N), and west (W) walls of the sarcophagus. The events begin with W1—on the west wall.

The stories of the Buddha and his various incarnations were widespread in Buddhist art on the Silk Road. Following in the footsteps of the Buddha, the Sogdian couple is represented as traveling from a past life to this life, and then eventually to a future life of spiritual awakening. To understand how illustrations of the Buddha’s life inspired the unique pictorial biography of the couple, we can look at the major scenes depicted on the sarcophagus.

Past life (West Wall 1)

The first scene on the sarcophagus shows the Sogdian couple in their past lives.

Left: Wirkak and Wiyusi in their past lives make offerings of lotus flowers; right: stone carving from Gandhara showing Prince Siddhartha (Buddha) and Yasodhara in their former lives. Left: detail, west wall 1, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: “The Dipankara jataka,” Gandhara (Pakistan), c. 2nd century (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The couple, on their knees, make offerings of lotus flowers (the symbol of awakening in Buddhism), to a Buddha-like figure.

This scene draws on the most celebrated episode in former life of Prince Siddhartha, in which he and his future wife, Yasodhara (at this point she is a flower-selling girl and he is a priest), perform the same pious deed in front of the Dipankara Buddha, a Buddha of the past.

In a stone carving from Gandhara (above right), we see the priest represented three times before the Dipankara Buddha: prostrating on the ground; offering a lotus flower; and praying in the sky. The flower-selling girl can be seen standing behind the priest, her right hand holding a flower.

Left: Divine figure on the Wirkak sarcophagus, west wall 1 and right: former incarnation of the Dipankara Buddha (“The Hare-king jataka”), Cave 14 at Kizil (Xinjiang, China), 6th century

The divine figure the couple approaches looks almost identical to a former life of the Dipankara Buddha depicted in a painting from Cave 14 at Kizil (Kucha, Xinjiang). Here, the Dipankara Buddha is shown waving his hands toward a hare in fire—the hare is an earlier incarnation of Prince Siddhartha who is willing to sacrifice his life to keep the ascetic warm.

Birth (West wall 2)

The representation of the Sogdian couple’s past lives is followed by a scene depicting the birth of Wirkak.

Left: Baby Wirkak with his parents, west wall 2, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: Queen Maya with the infant Siddhartha, Cave 290 at Dunhuang (Gansu, China), 6th century

According to the epitaph, Wirkak was born to an illustrious family in Central Asia. In this scene on the sarcophagus, baby Wirkak is held by his regally clad parents.

This recalls illustrations of an episode having to do with Prince Siddhartha’s birth. In Cave 290 at Dunhuang, a Buddhist cave chapel built in Wirkak’s days, the infant prince is in the arms of his mother, Queen Maya; the illustration is among 87 scenes about the Buddha’s life depicted. On Wirkak’s sarcophagus, the infant Siddhartha is similarly shown in the arms of his parent.

Coming of Age (W3)

A hunting scene following Wirkak’s birth speaks to his coming of age. Riding on horseback, he shoots at a group of running beasts with a bow. [1] The iconography resonates with Prince Siddhartha’s life. When he reached adolescence, he was said to possess such tremendous physical strength that an arrow shot by him penetrated seven iron drums at once.

Left: Wirkak hunting on horseback, west wall 3, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: Prince Siddhartha in archery contest, Cave 290 at Dunhuang

In a painted scene in Cave 290 at Dunhuang, the prince’s incredible feat is depicted in the scene of an archery contest. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the illustration of Wirkak’s adolescent years also focuses on his superb skill in archery.

Wedding (N2)

After migrating to Northwest China, Wirkak met his wife, who is portrayed in the next scene with him at an event that seems to be their wedding. Wearing ornate crowns, the groom and bride are surrounded by an entourage of musicians and attendants.

Left: Wedding of Wirkak and Wiyusi, north wall 2, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: Wedding of Siddhartha and Yasodhara, Cave 290 at Dunhuang

The composition of this scene was derived from illustrations of Prince Siddhartha’s wedding with Yasodhara. In yet another scene from Cave 290 at Dunhuang, the prince’s wedding scene also featured a musical band and a grand building. Like Prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara, the marriage of the Sogdian couple was likely believed to be predestined by their former incarnations. In the wedding scene, they reunite and will not be separated again.

Journey (N3)

As they passed their prime, the Sogdian couple moved to the the capital of North China (Xi’an), probably at the request of the Chinese emperor. In the next scene, the couple, both on horseback, can be seen setting out on their last journey on the Silk Road: Wirkak turns back, bidding farewell to friends. His wife Wiyusi leans forward, bracing herself for the arduous journey ahead.

Left: Wirkak and Wiyusi embarking on a journey (at the top), north wall 3, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: Prince Siddhartha encountering a sick man, Cave 6 at Yungang (Shanxi, China), 5th century AD

Some of the best-known stories about the Prince Siddhartha’s life are related to his short excursions from the palace (these are commonly called the “Four Encounters”). Under a giant parasol, Wirkak indeed looks like Prince Siddhartha on an outing, as illustrated in a cave chapel at Yungang (Datong, Shanxi)—instead of a traveler heading for a place hundred miles away. Nevertheless, the connection between these two life stories goes beyond solely formal similarity, as revealed by the following scenes on the sarcophagus.

Withdrawal from Life (N4–5)

Prince Siddhartha’s excursions away from the palace were a turning point in his life. It is said that the prince encountered an old man, a sick man, and a dead body on his travels, and these encounters prompted him not only to ponder the meaning of life, but also to ultimately abandon his princely role by taking a spiritual path. Although the Sogdian couple’s final journey was not quite as eventful, we see a parallel change in their attitude toward life.

Wirkak and Wiyusi in a feast with guests, north wall 4–5, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80

In the scene immediately following their departure for the Chinese heartland, the Sogdian couple enjoys a banquet with friends (possibly in celebration of Nowruz, the Iranian New Year). However, all the pomp and majesty of previous scenes disappears: the couple no longer wears crown-like headdresses. They are attired in plainer clothes, and they sit in a natural environment, surrounded by flowers and grapevines instead of splendid buildings.

Left: Wirkak in ascetic practice, north wall 4–5, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: Prince Siddhartha practicing asceticism, banner painting on silk, from Cave 17 at Dunhuang, 8th–10th century, British Museum

In the next scene, the elderly Wirkak seems to have withdrawn completely from life; he looks no different from Prince Siddhartha in his ascetic practice, as illustrated in a silk painting from Dunhuang. Like the emaciated and haggard prince, Wirkak is getting close to a spiritual awakening; this is signaled by a monkey prostrating before him. The message cannot be clearer: Wirkak progressed from a devout worshipper of the Buddha in his former life to a sacred and venerated figure toward the end of his present life.

Ascent to Paradise and Awakening (E1-3)

Crossing the Chinvat Bridge (below) and ascent to paradise (above), east wall 1–3, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80

The last three scenes on the sarcophagus are about the Sogdian couple’s journey after death, a journey which takes them to paradise and awakening. The first two scenes, as many scholars have pointed out, represent their souls passing through the so-called Chinvat Bridge—the bridge of judgement in Zoroastrianism—and ascending to paradise where they are received by the Sogdian God of Wind.

The couple’s journey continues into a final scene, where they soar on the back of winged horses escorted by heavenly musicians. This grand finale for the entire pictorial biography of the Sogdian couple resembles prevalent imagery of Prince Siddhartha making his escape from the palace (“the Great Renunciation”) when he leaves behind all worldly attachments to take a spiritual path. In Buddhist art, the episode is often treated as a symbol of Prince Siddhartha’s awakening, such as a scene at Dunhuang in which the prince is surrounded by flying deities, as if he is lifted to heaven. Likewise, the Sogdian couple’s flight in paradise indicates the ultimate destination of their spiritual journey.

Left: Wirkak and Wiyusi ascending to heaven, east wall 1–3, on the Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80; right: The Great Renunciation of Prince Siddhartha, Cave 329 at Dunhuang, 7th century

An epic journey

Today, the sarcophagus of Wirkak and Wiyusi is on permanent display in the Municipal Museum of Xi’an, the city where the Sogdian couple lived out the final days. There are many wonderful images on the sarcophagus not discussed in this essay. But if you get a chance to visit the museum someday, you will agree with me that none of these images are more inspiring than the scenes about the Sogdian couple’s epic journey across multiple lives. Modeled on the life of Prince Siddhartha and Yasodhara, these scenes demonstrate the inspirational power of Buddhist art on the Silk Road, which extended beyond geographic, cultural, and religious boundaries.

- Both the composition and style of this scene were borrowed from Sasanian silver plates, which often feature Sasanian kings engaged in the heroic act of hunting. Sogdians merchants were familiar with Sasanian gold and silver, and liked to have themselves portrayed as Sasanian kings—probably as a way to celebrate their Iranian roots.

Additional resources:

The Sogdians: Influencers on the Silk Roads

Julie Bellemare, “Shi Jun’s Sarcophagus,” in The Sogdians: Influencers on the Silk Roads, accessed March 1, 2021.

Albert E. Dien, “The Tomb of the Sogdian Master Shi: Insights into the Life of a Sabao,”The Silk Road 7

Frantz Grenet, “Religious Diversity among Sogdian Merchants in Sixth-Century China: Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Manichaeism, and Hinduism,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East vol. 27, no.2 (2007), pp. 463–478.

Yang Junkai, “Carvings on the Stone Outer Coffin of Lord Shi of the Northern Zhou,” in Les Sogdiens en Chine, edited by Étienne de la Vaissière and Éric Trombert (Paris: École française d’Extrême-Orient, 2005), pp. 21–46.

Jin Xu, “A Journey Across Many Realms: The Shi Jun Sarcophagus and the Visual Representation of Migration on the Silk Road,” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 80, no. 1 (2021), pp.145–165.