Altneushul, Prague (photo: Øyvind Holmstad, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In architecture, there is often a dominant mode of design in a given country or region at a particular moment in history. In central and western Europe during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it was customary to use Gothic elements such as pointed arches, rib vaults, and thin walls filled with stained glass.

But what about minority groups? Did they follow the trends of the majority or were they told what and how to build by the majority culture? Did the minorities have architects of their own on whom to rely, or were the minority members excluded from certain professions? We know about exclusion and discrimination from modern history. But what happened in the later middle ages?

Jews in Medieval Europe

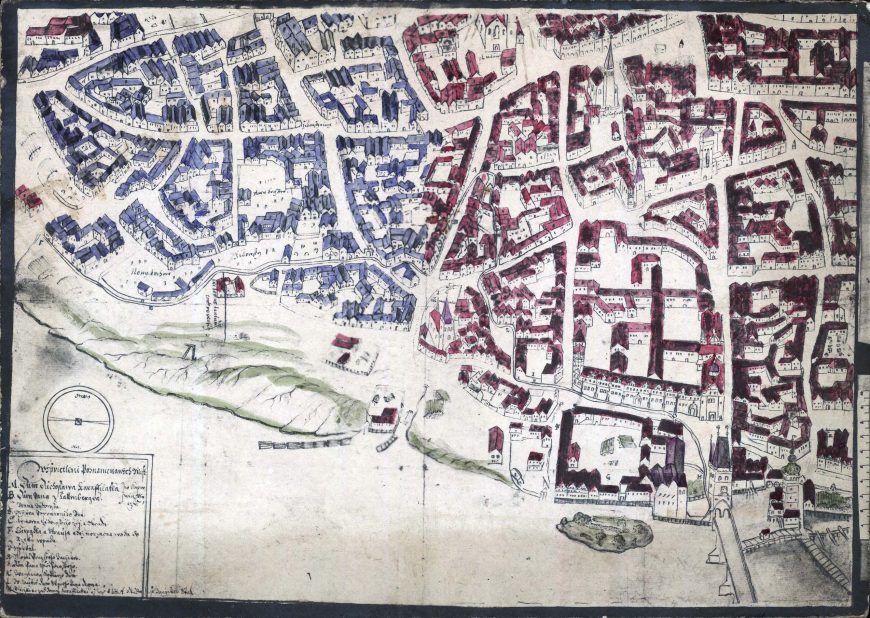

For centuries, Jews were the most noticeable minority in Europe. They lived only in certain regions, and were excluded from others. Their numbers were usually restricted, even in places where they were allowed to live. Nevertheless, Jews were useful members of society, in part because most Jewish men were literate—they were, and still are, expected to read their prayers (poor Roman Catholics had no schools and relied on priests to read on their behalf). Literate people could be useful in commerce and in keeping records, so some rulers allowed Jews to live in their cities. Often, there was a district designated for Jews, perhaps near the commercial district of a city, near the city walls, or near the palace of the ruler whom they served, (there were formal walled ghettoes only from the mid-sixteenth century onward).

Křižovnický plán (Map of Prague), 1665. Archiv hlavního města Prahy showing Josefov (Prague’s Jewish quarter) in blue

Synagogue architecture

Every Jewish community had to have a place of worship, called a synagogue (from a Greek word related to assembling). Only a few rules governed the design of a synagogue; these rules were found in the Talmud. Later congregations of Jews adhered to these rules as best they could, despite the restrictions on their residence and use of land. Ideally, a synagogue’s focal point, the end of the building’s central axis, would face Jerusalem (to the southeast from the city of Prague).

The synagogue would contain carefully hand-written scrolls of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible that were held in chest known as a Torah ark when not in use. The ark was located at the building’s focal point. When the scrolls were removed from their storage chest, they would be carried ceremoniously to the center of the synagogue where the elders of the congregation would mount a low platform (bimah) and place the scrolls on a reading table. It would be an honor to be called to read to the congregation. In addition, no one was allowed to live above the synagogue; religious activity was to have pride of place and women would not occupy the same part of the building as men in order to avoid distracting the men from their prayers. Animals and other unclean things were not be allowed to defile the synagogue interior.

View with bimah at left, Altneushul, Prague (photo: Chajm Guski, CC BY-SA 2.0)

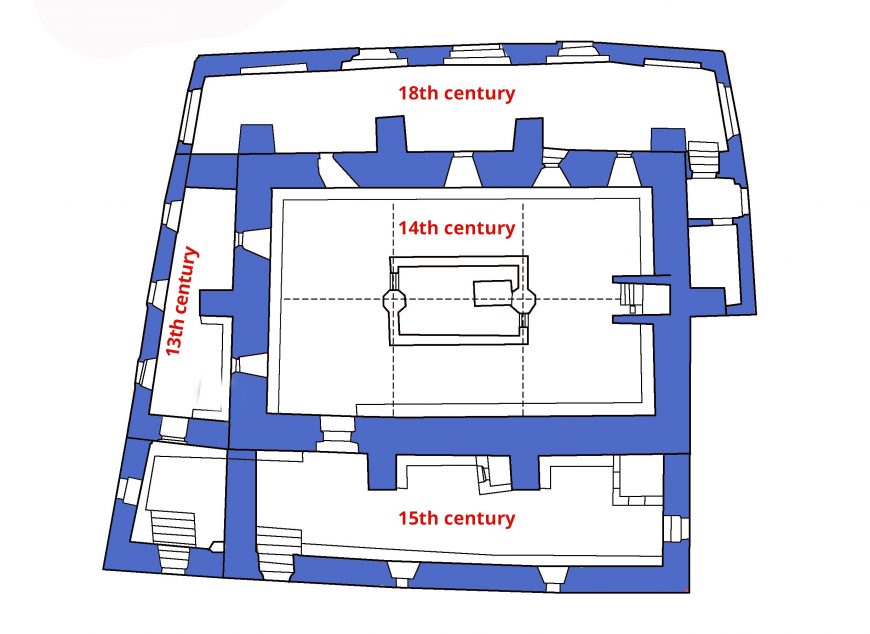

The Altneushul: a Gothic synagogue

An important late medieval synagogue in Prague is called the Old New Synagogue because the city later gained a newer New Synagogue. It is generally known as the Altneushul in Yiddish. It seems to have originally been a small rectangular building erected in the thirteenth century, but late in that century or in the next one, the original synagogue was enlarged. Both stages of construction were apparently designed and built by Christians, because Jews were either formally or tacitly excluded from the guilds (trade associations) of the building crafts. An architect who at other times worked on churches seems to have been in charge because ornamental details are similar to those of a local church; the architect was therefore almost certainly Roman Catholic.

The synagogue stands in what was once the heart of the Jewish quarter. Its floor is lower than the level of the street in order to allow the congregation to utter the words of Psalm 130:1, “Out of the depths, I cry to Thee, O Lord.” The location has become all the more noticeable over time as the level of nearby streets has risen with re-paving, and as Pařížská (Paris Street), just to the east, was built in the nineteenth century to clear part of the old, crowded Jewish neighborhood.

Rib vaulting, Altneushul, Prague (photo: Peco~commonswiki (?), CC BY-SA 2.5)

The Altneushul, beyond the vestibule, is a rectangle about 26 feet wide and 45 feet long. It is composed of six bays arranged in two aisles, each with three bays. On the long east-west axis in the center of the building, two slender octagonal pillars allow the interior to be wider than it would have been without these supports. Leaf forms adorn the capitals.

Rib vaults cover each bay, but unlike the four-part, X-shaped ribs found in many Gothic-style vaults, those at the Altneushul have an extra, fifth rib, probably to help ensure stability; the same design can be seen in some secular and Christian buildings of the time. The bimah stands between the octagonal pillars in the center of the synagogue, and the ark on the eastern wall terminates the principal axis of the interior.

A place for prayer and study

This is clearly not the plan of a church. Jews had no need for a church plan with a nave, side aisles, chapels, and a transept because their rituals and customs differed from those of Roman Catholics. Instead, the plan of the Altneushul is more similar to the plan of certain secular buildings, as well as to some chapter houses. The plan of a meeting room was useful for a synagogue in which men meet to read and discuss religious doctrine. When possible, Jews and the Christians would not have wanted to imitate each other’s religious architecture, although in some of the simplest churches, chapels, and synagogues, a single room had to suffice for the congregation. Nevertheless, because members of both religions used the same builders, the individual components or ornamental details of the various buildings often resemble each other in design. The Altneushul has only plant decoration, because at that time, Jews would not allow images of human beings within a religious context.

Tympanum, Altneushul, Prague (photo: Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, CC BY 2.0)

Seats and desks are distinctive features of a medieval synagogue; medieval churches had no seats and there was no need for desks since most Christians were not literate. Seats are necessary in synagogues because Jews spend hours there, reading their own prayers—in the middle ages, each man did so at his own pace—and discussing religious doctrine. Books were placed on the desks during the reading, and were later stored inside the desks for the next day’s prayer and study meetings, along with the prayer shawls worn during religious services. In the Altneushul, the seats either face the bimah, or are arranged around the bimah platform; the ones we see today are neo-Gothic but reflect the original arrangement. This disposition assures that everyone is close to the bimah where the Torah portion is read each day. Members of the congregation faced each other during prayer, and that practice enhanced the sense of community. This is different from the practice in churches of that time, where the clergymen led Roman Catholics who stood one behind another and listened to a single authoritative voice.

Desks, Altneushul, Prague (photo: Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, CC BY 2.0)

Lighting fixtures are important in synagogues because each man must read the essential texts. In this building, the windows are small, either for customary or structural reasons or to prevent vandals from breaking large and expensive windows. Therefore, artificial lighting was needed and was provided by candlesticks but also by hanging lamps and other devices; the ones in place today are post-medieval.

Often, the bimah was made of wood, with a railing around it. The reading desk on the bimah faced the ark. In the Altneushul, the bimah is a delicate metal construction from the late fifteenth century that allows members of the congregation to easily see the reader. Both the entrance door and the pointed gable over the ark have carved decoration showing vines and fruits, though the ark is often concealed by a handsome curtain placed over it.

Opening to women’s area, Altneushul, Prague (photo: Chajm Guski, CC BY-SA 2.0)

And the women?

So far, this essay has mentioned only men. Where were the women if they were not permitted in the main room of the synagogue? Evidence suggests that in early centuries, they were either excluded from synagogue activity or were accommodated in annexes. By the fourteenth century, a first women’s annex was built at the Altneushul with small windows that opened to the main room where the men gathered. This allowed women to hear the prayers but not to see the men or be seen by them. In the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, the congregation built additional annexes to accommodate the increasing numbers of women who elected to, or were allowed to, attend religious services. In the late middle ages, too, the high saddle roof and the brick gable were added, making the synagogue more prominent in the neighborhood.

Loss and survival

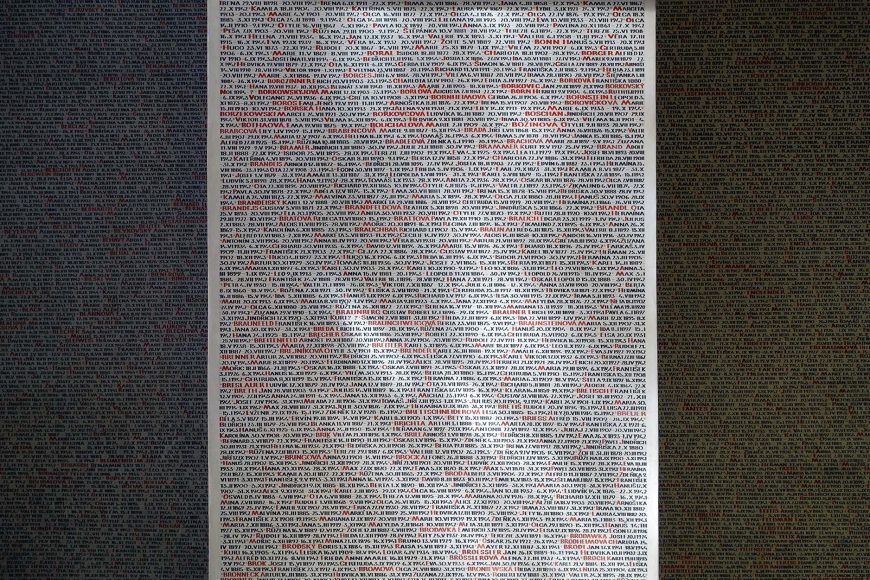

Given the horrors perpetrated against European Jews during the Second World War, it may seem surprising that this building and several later synagogues in Prague have survived. The Pinkas Synagogue from the late fifteenth century is now a memorial; its walls are painted with the names of over 77,000 Czech Jews who were deported and murdered.

Perversely, the Nazis and their collaborators left these buildings standing in order to provide the setting for a museum of a vanished people that was to contain artifacts collected from the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia and material from an early twentieth-century Jewish museum. These objects are now displayed in several of the other surviving synagogues in Prague, but the Altneushul, as the oldest survivor, has been left to illustrate the appearance of an unusually distinctive medieval synagogue.

Additional Resources:

Arno Pařik, Dana Cabanova, Petr Kliment, Prague Synagogues, Prague, Jewish Museum, 2000

YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

Carol Herselle Krinsky, Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning, New York, Architectural History Foundation, rev. ed., 1988