Illustrated scrolls of an 11th-century tale provide a fascinating look into Heian-period court life, particularly the lives of noble women.

The Tale of Genji illustrated handscroll (Genji Monogatari Emaki, 源氏物語絵巻), c. 1130, ink and color on paper scrolls, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya). Speakers: Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara and Dr. Steven Zucker

0:00:06.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: One of the most famous works of literature to come down to us is the Tale of Genji.

0:00:12.8 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: The Tale of Genji, or Genji Monogatari, was written in Heian Japan by a court lady whose name is Murasaki Shikibu.

0:00:23.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: Now she was, we think, a sort of mid-ranked noblewoman. That is, she would have been in the imperial court and highly educated. And as a result, she’s able to give us access to court culture at this time in the 11th century.

0:00:41.0 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: The Tale of Genji narrates the life and loves of Hikaru Genji, otherwise known as the Shining Prince. He’s the son of the emperor and a low-rank consort.

0:00:52.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: Some people have gone so far as to say this is the first novel. But more precisely, people say that this is the first psychological novel. This is the first novel that emphasizes what people are thinking, what people are feeling, and the social mores of this culture. And although we refer to this text as a novel, there is no single plot. It is instead a series of vignettes that follow the lives of the people of the imperial court and others.

0:01:22.7 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: This is a really fascinating insider’s account of what life was like for these women who lived within these palatial grounds. And Murasaki Shikibu was privy to many of these episodes that would happen within these grounds.

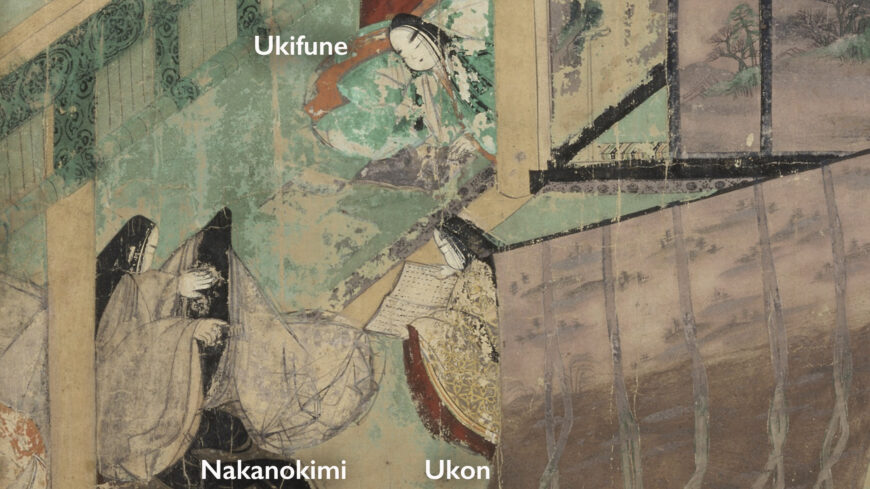

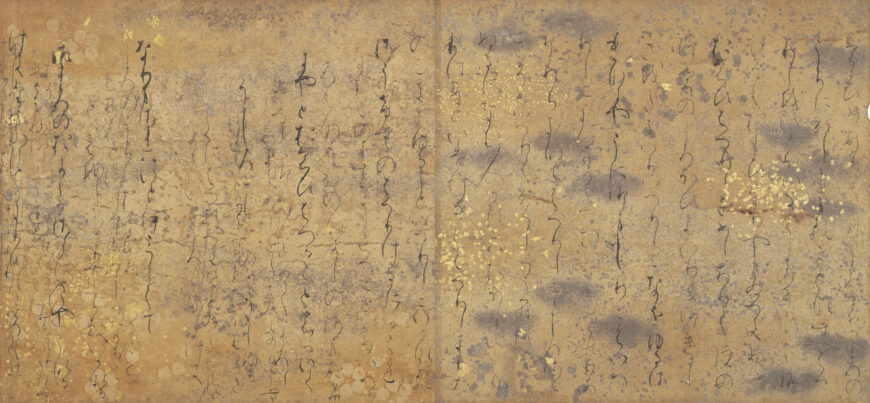

0:01:40.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: But the original manuscript is lost. And what we’re looking at is a set of excerpts produced about a hundred years after this was first written. And so it’s important to understand the paintings as embedded in the text within hand scrolls that would have been rolled and unrolled section by section in order to be read. These paintings and these written excerpts were produced with meticulous care on extremely fine paper with lavish decoration and a kind of elegance in the script that has been celebrated for centuries. This image is similar to almost all of the surviving paintings in that it is showing an interior scene. It’s using a technique called the roof blown off. That is to say that we seem to be hovering somehow above the building looking in. We have this privileged view of this domestic scene that is taking place within a palace that we should not have access to.

0:02:41.3 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: Exactly, and we have to remember that women during this time in Heian, Japan, aristocratic women in particular, were very much secluded from public life, from socialising, and a lot of these women were often not seen by anyone else other than their husbands or their fathers and their inner circles. So this really is a very private scene which we have stumbled onto.

0:03:08.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: The painting is over a thousand years old, and so it has deteriorated. These are paintings that do not use the Western tradition of linear perspective, and so there is a kind of flattening as a result that can be a little bit hard to read initially.

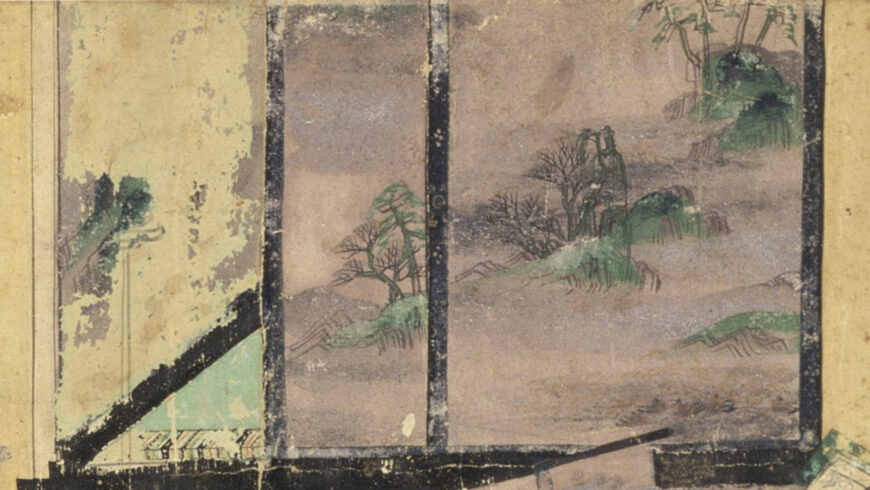

0:03:22.3 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: That’s right. When you first encounter this scene, you get a sense that you are looking at the various points throughout the composition, but when you do settle down, you see that the artist actually guides you to look at a particular point in the painting. We see a standing curtain known as the kichō, and that’s been strategically erected in the middle of the composition. The curtains’ function is to shield the activities of the women in the room, and then you have the fusuma, or the sliding doors, and these rolled-up curtains, and together with the directional lines of the standing curtain, they lead you towards the left of the composition where the main activity is taking place.

0:04:12.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: And there we see four women, three principal figures and an attendant.

0:04:16.7 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: We have Nakanokimi, who’s seated on the left, and her attendant is combing her hair. It seems like she’s just stepped out of her shower because she’s not wearing her full 12-layered robe. Next to Nakanokimi, we have Ukon, who’s reading, and then we have Uki fune, who is looking at illustrations accompanying this text being read.

0:04:41.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: Nakanokimi is given a degree of importance in this composition. Lines seem to move towards her. There is this grid that exists where horizontals are parallel to the picture plane, but then there is one dominant set of diagonals that are also parallel to each other, with one exception, the standing silk screen, which has its own diagonal, but helps to create an arrow that points directly to this figure. And she’s partially hidden by the silk curtain, which I find fascinating, because on it, is a painted landscape that is separated by these beautiful ribbons that fall from the top, creating both a sense of deep space and simultaneously, a flattened space, in contrast to the other representation of a landscape, which is just above it on the sliding screens, both of which tease us about the actual natural world, which is beyond that open door, which we are not allowed to see.

0:05:41.4 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: So there is a lot of referencing of these nature motifs. We can see this repeated several times in this composition. We see it on the kimonos that they’re wearing. We see it on the fusuma, or the sliding doors. We see it on the standing screen, and right down to these rather abstract motifs on the rolled curtains, reinforcing the idea of the interiorization of nature, bringing nature inside.

0:06:08.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: It’s interesting that the one figure whose face we are given access to is the figure that is furthest from us.

0:06:14.8 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: Ukifune has come to live with Nakanokimi, and she often consults Nakanokimi on matters of the heart. Ukifune represents a bit of a tragic figure. Because of her lower status, she’s been rather unsuccessful in affairs of the heart, and we understand that, later on, Ukifune attempts suicide, but she turns away from this material world and goes off to join a monastery.

0:06:43.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: And so I always believed that the increasingly literary culture of the Japanese court was a direct result of the introduction of Buddhism centuries earlier.

0:06:53.8 Dr. Eve Loh-Kazuhara: Illustrated scrolls, or emaki, were introduced to Japan from China, particularly during the spread of Buddhism.

0:07:02.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: This is such a lavish and beautiful image, and one can only imagine what it would have been like to look at these paintings embedded within panels of script that were every bit as alive as these images, where the script is a layer atop, a highly decorative background, so that there is almost a kind of seamlessness between text and image as the stories unfold.

Azumaya scene (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (源氏物語絵巻), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

The image above, which shows the private lives of female courtiers in the royal palace in Kyoto, comes from the classic story and first major literary work written by a woman (Murasaki Shikibu), the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語 ). The Tale of Genji was written a thousand years ago, in the first years of the 11th century, and is attributed to a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji is a complex novel that focuses on the romantic interests and entanglements of prince Genji and his entourage. It provides a fascinating entryway into Heian-period court life, complete with the aesthetic principles and practices of its residents.

In this image, we see three main female characters from a chapter in the Tale of Genji—Nakanokimi, Ukon, and Ukifune (together with three other figures) seated in a room.

Nakanokimi, Ukon, and Ukifune (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

A courtly culture

The story takes place in the royal palace in Kyoto during the Heian period in Japan. We see Nakanokimi attended to by her lady-in-waiting who combs her hair while Ukon reads to her. Ukifune, seated opposite Nakanokimi, looks at illustrations accompanying the text being read. Nakanokimi’s face is not visible, viewers are treated to her back profile instead. All the women wear their hair down in a fashion that adheres to the Heian beauty ideal for noble women, but only Nakanokimi’s long flowing black hair is highlighted. This detail emphasizes her high status among the courtiers, and at the same time, heightens the suspense of this private scene.

Dividers (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Aristocratic women in Heian Japan were forbidden from publicly socializing and were confined to living sheltered lives within the palace. In this scene, several interior devices double as privacy shields within these palatial spaces. The standing curtain (kichō) is erected strategically to obscure the activities of Nakanokimi and her company. The privacy of this setting is further enhanced by rolled curtains that can be lowered to separate the external world, in this case, the garden from the interiors. Just beside Ukifune, sliding doors (fusuma) further close in on the women in the room. The strategic placement of the kichō, the directional gaze of the women, and compositional lines demarcating space in this private room direct our attention to the bottom left of the composition where the three main characters sit.

A National Treasure

Although there are other surviving early Tale of Genji scrolls in different states of preservation, the significance of this scroll lies in its designation as one of the National Treasures of Japan. Apart from it being the oldest depiction of the Tale of Genji in existence, this scroll also stands out for a few notable reasons. The all-women scene serves as a poignant reminder of the role noble women authors had in the blossoming of literature during this period. It also provides an insight into the private lives, social norms, and beauty ideals prevalent in Heian Japan. For all the excitement and drama that the Tale of Genji offers, this particular scene is a testament to the literary contributions of ladies-in-waiting during the Heian period.

Fusuma (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

This particular scroll was once over 1 meter long. While the scroll has deteriorated, we can imagine the original vibrant colors and intricate details that once adorned it. Nature has always been an endearing and inspirational subject to Japanese artists and we see this from the patterns and motifs on the layered kimonos to the landscapes on the kichō and fusuma. These artistic renderings bring the natural world closer into the secluded lives of the women living in these palatial residences.

Kaimami (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Though they don’t survive in this scroll, illustrations for the Tale of Genji often show men and women interacting or peeping from behind folding screens, partitions, or fences. The act of covertly peeping (kaimami) is presented numerous times throughout the tale, functioning as a precursor to a romantic relationship. This covert behavior adhered to social norms of the time which upheld expectations that women could only be seen by their fathers, husbands, and inner circles. However, this did not mean that intimate relationships did not form—monogamous and polygamous affairs are chronicled in the Tale of Genji.

Ukifune (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Style, composition, and script

Several stylistic characteristics observed here are consistent with the illustrations of the genre and era. Note how the facial features are similarly drawn with “dashes for eyes and a hook for the nose” in what is known as hikime kagibana. Although this stylization makes it harder to discern the individual traits of characters, readers can place characters with the help of calligraphic passages preceding the illustrations and rely on their familiarity with the text.

An example of fukinuki yatai, here the roof of interior at the left is removed to allow for a view within (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

When portraying the interiors of palaces and residences, a compositional technique called fukinuki yatai is employed. This technique renders the building without its roof and ceiling so that an aerial perspective is possible.

Hiragana script, Chapter Kashiwagi Ⅱ (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

One of the significant aspects of the Tale of Genji was that it was written mainly in hiragana (a phonetic writing script based on the sounds of the Japanese language) and kanji (writing script using characters adopted from China) as opposed to it being strictly in the latter, which was predominantly reserved for use in official settings by highly-educated men well-versed in Chinese classics. Hiragana, on the other hand, was more accessible to women and common people. It was considered feminine, with a cursive script often thought to be more graceful than kanji. Women writers in the Heian period, including Murasaki (author of the Tale of Genji) and Sei Shōnagon (author of the Pillow Book), wrote their literary masterpieces in hiragana.

The Tale of Genji comprises 54 chapters and includes around 800 waka. Waka poems were written to convey multiple ideas on religious beliefs, beauty as expressed in nature, the changing seasons, and the transience and impermanence of life (a concept known as mono no aware). Waka was the primary mode of communication between lovers who exchanged them in courtship. The ability to compose waka proficiently enhanced a male courtier’s success at court and in love. Some of these exchanges as imagined by Murasaki are written into the Tale of Genji alongside her compositions as commentary on various events and scenes.

Modern copy of scroll 2 of the Genji Monogatari Emaki rolled up, 1911 (National Diet Library, Tokyo)

Scrolls

Illustrated scrolls or emaki were introduced to Japan from China during the spread of Buddhism. They usually depict historical events and religious teachings or provide social commentary such as that seen in the Tale of Genji. Scrolls became popular during the Heian period due to the rise of Buddhism and an emerging aristocratic class. As Buddhism spread, religious leaders and patrons commissioned literature and art to impart Buddhist teachings.

As both text and image form an integral part of these emaki, a collaborative effort from several people was required. The scrolls unravel from right to left and narrate a story in a continuous sequence: a piece of text would generally precede an accompanying painting. A calligrapher was in charge of scribing and a lead artist with his team took charge of the illustrations. A lead artist known as the sumigaki (ink line artist) would be responsible for planning and drawing the outlines of the composition. He would then add further details and instruct his team of artists to fill in different areas with prescribed colors. The colors are applied in layers that are built up in a process described as tsukuri-e (opaque colors obscuring the drawing beneath). This scroll was likely part of a series taken out to be enjoyed and put away afterwards.

There are no fixed number of illustrations or volumes for the emaki as they are produced in accordance with patrons’ requests. In the case of the Tale of Genji, commissions were often requested from some of the more famous and exciting chapters. This deliberate unravelling of the emaki adds suspense and anticipation, much like the thrill felt stumbling onto this private scene of the ladies-in-waiting.