Azuyama scene (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (源氏物語絵巻), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

The image above, which shows the private lives of female courtiers in the royal palace in Kyoto, comes from the classic story and first major literary work written by a woman (Murasaki Shikibu), the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語 ). The Tale of Genji was written a thousand years ago, in the first years of the 11th century, and is attributed to a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, Murasaki Shikibu. The Tale of Genji is a complex novel that focuses on the romantic interests and entanglements of prince Genji and his entourage. It provides a fascinating entryway into Heian-period court life, complete with the aesthetic principles and practices of its residents.

In this image, we see three main female characters from a chapter in the Tale of Genji—Nakanokimi, Ukon, and Ukifune (together with three other figures) seated in a room.

Nakanokimi, Ukon, and Ukifune (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

A courtly culture

The story takes place in the royal palace in Kyoto during the Heian period in Japan. We see Nakanokimi attended to by her lady-in-waiting who combs her hair while Ukon reads to her. Ukifune, seated opposite Nakanokimi, looks at illustrations accompanying the text being read. Nakanokimi’s face is not visible, viewers are treated to her back profile instead. All the women wear their hair down in a fashion that adheres to the Heian beauty ideal for noble women, but only Nakanokimi’s long flowing black hair is highlighted. This detail emphasizes her high status among the courtiers, and at the same time, heightens the suspense of this private scene.

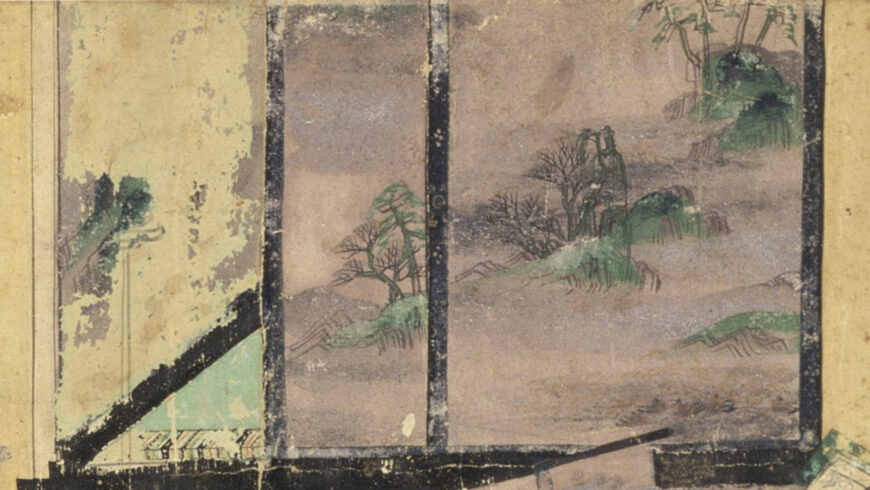

Dividers (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Aristocratic women in Heian Japan were forbidden from publicly socializing and were confined to living sheltered lives within the palace. In this scene, several interior devices double as privacy shields within these palatial spaces. The standing curtain (kichō) is erected strategically to obscure the activities of Nakanokimi and her company. The privacy of this setting is further enhanced by rolled curtains that can be lowered to separate the external world, in this case, the garden from the interiors. Just beside Ukifune, sliding doors (fusuma) further close in on the women in the room. The strategic placement of the kichō, the directional gaze of the women, and compositional lines demarcating space in this private room direct our attention to the bottom left of the composition where the three main characters sit.

A National Treasure

Although there are other surviving early Tale of Genji scrolls in different states of preservation, the significance of this scroll lies in its designation as one of the National Treasures of Japan. Apart from it being the oldest depiction of the Tale of Genji in existence, this scroll also stands out for a few notable reasons. The all-women scene serves as a poignant reminder of the role noble women authors had in the blossoming of literature during this period. It also provides an insight into the private lives, social norms, and beauty ideals prevalent in Heian Japan. For all the excitement and drama that the Tale of Genji offers, this particular scene is a testament to the literary contributions of ladies-in-waiting during the Heian period.

Fusuma (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

This particular scroll was once over 1 meter long. While the scroll has deteriorated, we can imagine the original vibrant colors and intricate details that once adorned it. Nature has always been an endearing and inspirational subject to Japanese artists and we see this from the patterns and motifs on the layered kimonos to the landscapes on the kichō and fusuma. These artistic renderings bring the natural world closer into the secluded lives of the women living in these palatial residences.

Kaimami (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Though they don’t survive in this scroll, illustrations for the Tale of Genji often show men and women interacting or peeping from behind folding screens, partitions, or fences. The act of covertly peeping (kaimami) is presented numerous times throughout the tale, functioning as a precursor to a romantic relationship. This covert behavior adhered to social norms of the time which upheld expectations that women could only be seen by their fathers, husbands, and inner circles. However, this did not mean that intimate relationships did not form—monogamous and polygamous affairs are chronicled in the Tale of Genji.

Ukifune (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

Style, composition, and script

Several stylistic characteristics observed here are consistent with the illustrations of the genre and era. Note how the facial features are similarly drawn with “dashes for eyes and a hook for the nose” in what is known as hikime kagibana. Although this stylization makes it harder to discern the individual traits of characters, readers can place characters with the help of calligraphic passages preceding the illustrations and rely on their familiarity with the text.

An example of fukinuki yatai, here the roof of interior at the left is removed to allow for a view within (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

When portraying the interiors of palaces and residences, a compositional technique called fukinuki yatai is employed. This technique renders the building without its roof and ceiling so that an aerial perspective is possible.

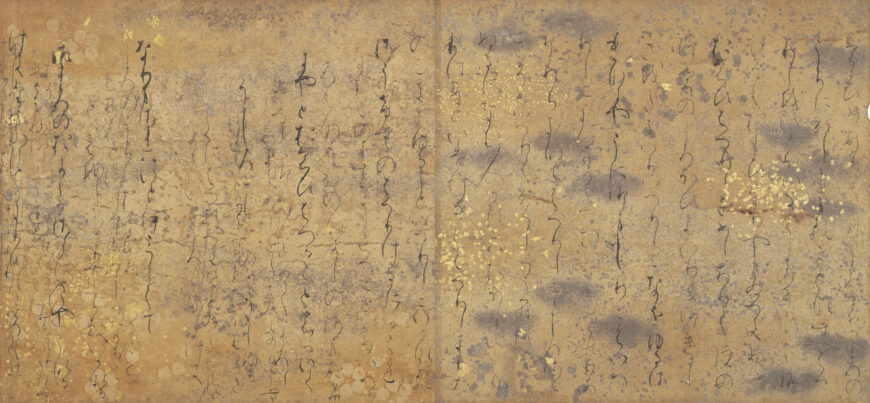

Hiragana script, Chapter Kashiwagi Ⅱ (detail), Genji Monogatari Emaki (scroll), c. 1130, ink and color on paper, 22 x 23 cm (Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya)

One of the significant aspects of the Tale of Genji was that it was written mainly in hiragana (a phonetic writing script based on the sounds of the Japanese language) and kanji (writing script using characters adopted from China) as opposed to it being strictly in the latter, which was predominantly reserved for use in official settings by highly-educated men well-versed in Chinese classics. Hiragana, on the other hand, was more accessible to women and common people. It was considered feminine, with a cursive script often thought to be more graceful than kanji. Women writers in the Heian period, including Murasaki (author of the Tale of Genji) and Sei Shōnagon (author of the Pillow Book), wrote their literary masterpieces in hiragana.

The Tale of Genji comprises 54 chapters and includes around 800 waka. Waka poems were written to convey multiple ideas on religious beliefs, beauty as expressed in nature, the changing seasons, and the transience and impermanence of life (a concept known as mono no aware). Waka was the primary mode of communication between lovers who exchanged them in courtship. The ability to compose waka proficiently enhanced a male courtier’s success at court and in love. Some of these exchanges as imagined by Murasaki are written into the Tale of Genji alongside her compositions as commentary on various events and scenes.

Modern copy of scroll 2 of the Genji Monogatari Emaki rolled up, 1911 (National Diet Library, Tokyo)

Scrolls

Illustrated scrolls or emaki were introduced to Japan from China during the spread of Buddhism. They usually depict historical events and religious teachings or provide social commentary such as that seen in the Tale of Genji. Scrolls became popular during the Heian period due to the rise of Buddhism and an emerging aristocratic class. As Buddhism spread, religious leaders and patrons commissioned literature and art to impart Buddhist teachings.

As both text and image form an integral part of these emaki, a collaborative effort from several people was required. The scrolls unravel from right to left and narrate a story in a continuous sequence: a piece of text would generally precede an accompanying painting. A calligrapher was in charge of scribing and a lead artist with his team took charge of the illustrations. A lead artist known as the sumigaki (ink line artist) would be responsible for planning and drawing the outlines of the composition. He would then add further details and instruct his team of artists to fill in different areas with prescribed colors. The colors are applied in layers that are built up in a process described as tsukuri-e (opaque colors obscuring the drawing beneath). This scroll was likely part of a series taken out to be enjoyed and put away afterwards.

There are no fixed number of illustrations or volumes for the emaki as they are produced in accordance with patrons’ requests. In the case of the Tale of Genji, commissions were often requested from some of the more famous and exciting chapters. This deliberate unravelling of the emaki adds suspense and anticipation, much like the thrill felt stumbling onto this private scene of the ladies-in-waiting.