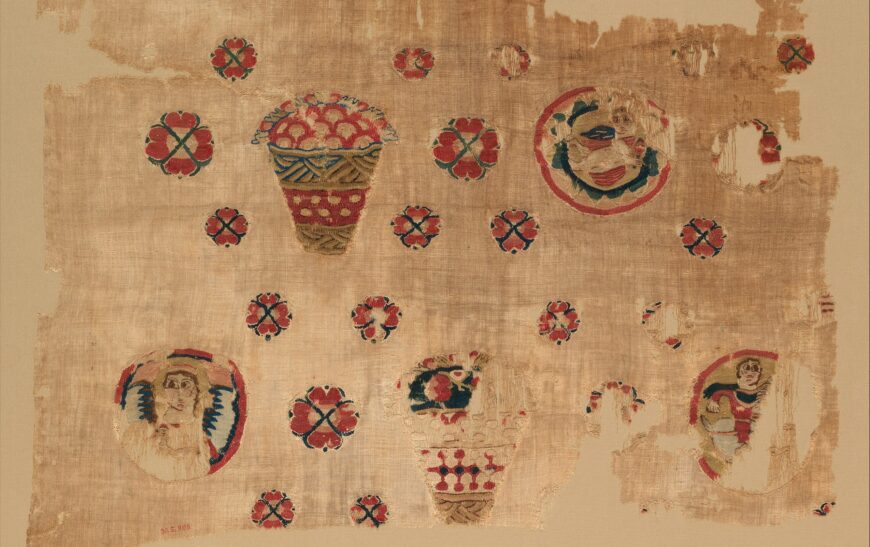

Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This late antique Egyptian textile, depicting mounted riders, winged women, and various motifs of prosperity, provides a glimpse into the multiculturalism and complex social structures of the Mediterranean world. Discovered in an Egyptian cemetery, its preservation is largely due to Egypt’s dry climate. This essay explores the textile’s themes of victory, success, and otherness while examining how Black figures within the composition raise questions about race, identity, and representation in antiquity.

Form and context

The textile, likely once part of a larger wall hanging, exemplifies the vibrant visual language of late antique Egypt during the early Christian period (c. 150–700). Woven from linen and wool, it is characterized by a rich color palette, primarily reds, blues, and greens, set against a natural linen ground. Despite its fragmentary condition, the textile preserves a complex and dynamic composition of repeated figural and ornamental motifs. The upper register features mounted horsemen, each rendered in silhouette-like blackwool, possibly hunters, brandishing weapons and accompanied by hounds in pursuit of prey. The hunters are adorned with Phrygian caps, an accessory associated with the West Asia. They hold stones and bows, which are common symbols in hunting scenes of late antiquity. Hunting was a prevalent motif, often signifying aristocratic excess or victory over death at the time of the Last Judgment.

Medallions containing portraits above arched panels with mounted horsemen (detail), Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

These figures appear within arched panels framed by geometric and floral borders, suggesting a rhythmic narrative cycle or ceremonial procession. Above them are medallions containing bust-length portraits of winged women, depicted frontally with large eyes and stylized hair.

Baskets, floral rosettes, and medallions (detail), Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The lower register contains more abstracted and symbolic motifs: stylized baskets of fruit, rosettes, and another winged figure and man on horseback, rendered in pink and white threads. The basket motif, frequently interpreted as a symbol of abundance or prosperity, is flanked by repeating floral rosettes that act as visual anchors, unifying the composition and creating a sense of movement and symmetry.

Woven texture (detail), Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The textile uses a weft-loop tapestry technique woven into a linen ground that demonstrates the advanced skill of late antique Egyptian weavers. The contrasts between the flat, linear forms of the figures and the intricate patterning reveal an aesthetic that valued ornamental richness. This hanging fragment embodies the eclectic cultural milieu of Coptic Egypt, where Greek, Roman, Christian, and local Egyptian traditions coexisted and fused in the visual arts.

The figures and symbols, while accessible, also evoke deeper liturgical or domestic meanings, making this fragment both a decorative and communicative object within its original context. The textile’s materials and craftsmanship speak to its value and the social standing of its owner. Such luxurious textiles were reserved for elite households and used for display in domestic settings. They had a second use in burial settings where the owners buried themselves with these valuable materials. Textiles in late antiquity were not just functional but also served as powerful visual tools for communicating cultural, religious, and social values.

Section with missing pieces (detail), Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Though we lack a precise archaeological context, the textile’s worn condition and ancient repairs suggest its long-term use and care. The multicultural society of late antique Egypt during this period was a crossroads of cultures. Multiple languages, including Greek, Coptic, Latin, Arabic, Ethiopic, and Old Nubian, were spoken and written, reflecting its diverse populations. The textile’s deliberate inclusion of figures with distinct skin tones hints at this multicultural environment. Black figures, clad in foreign dress, raise questions about their roles and significance within elite spaces. Were these figures meant to symbolize exoticism, power, or “otherness”? While scholarship has yet to address this directly, their inclusion challenges assumptions of homogeneity in late antique art.

Blackness, otherness, and textual parallels

To understand perceptions of Blackness in late antiquity, we turn to textual sources, such as The Sayings of the Desert Fathers (written around the 3rd to 5th centuries C.E.). One parable describes Abba Moses, a Black monk in an Egyptian monastery, facing prejudice when other monks derisively ask, “Why does this Black man come among us?” Abba Moses’s stoic response of silence underscores his humility but also reveals how skin color could be used as a tool of exclusion. [1]

Mounted horseman (detail), Fragment from a Coptic Hanging, 5th century (attributed to Egypt), linen, wool, plain weave and tapestry weave, 104 x 63 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This story offers insight into the textile’s mounted riders. Figures depicted with darker skin may have conveyed “otherness” to viewers, much like Abba Moses’s reception among his peers. However, their portrayal alongside motifs of victory and prosperity suggests a more nuanced relationship. In late antique Egypt, skin color carried layered meanings shaped by cultural, religious, and political contexts.

Modern interpretations and the problem of erasure

Modern scholarship and museum practices further complicate interpretations of the textile. Museums have begun to reconsider the language used in object descriptions. Words like “African” have sometimes been omitted in efforts to be inclusive. However, as Frank M. Snowden Jr., a pioneering scholar of Africans in antiquity, emphasized, ancient representations of Black individuals closely align with racial types recognized today. In Before Color Prejudice, Snowden argued for the visibility of Africans in ancient Mediterranean societies, highlighting their diversity and contributions. [2]

It is essential to address this erasure and recognize the cultural significance of such works. Removing ethnic descriptors, while well-intentioned, risks diminishing the historical record and the visibility of diverse communities in antiquity. In textiles like this, the presence of figures with darker skin tones is deliberate and meaningful. By acknowledging their existence, we honor the complexity and interconnectedness of the ancient world.

Conclusion

This late antique Egyptian textile provides a striking glimpse into the diversity and cultural complexity of the Mediterranean world. Its depiction of mounted riders, winged women, and symbolic motifs of victory and prosperity reflects both elite ideals and the multiculturalism of late antique Egypt. The deliberate inclusion of figures with darker skin tones invites viewers to grapple with themes of identity, otherness, and power. Furthermore, it serves as a reminder of the historical presence and contributions of Black communities in antiquity. By engaging thoughtfully with these representations, we acknowledge their significance and ensure their rightful place in our collective history.