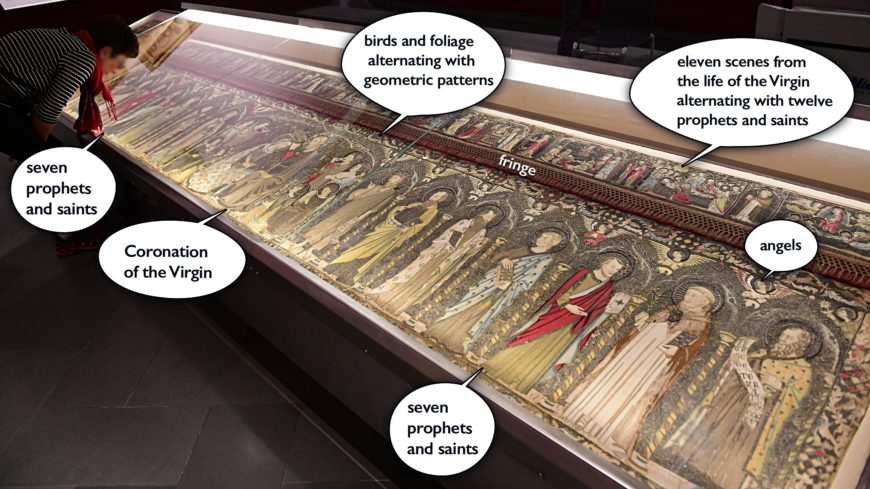

Coronation of the Virgin, musician angels, and a saint in a niche on either side (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar front on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An altar frontal

Of the more than a million visitors to the Accademia in Florence who go to see Michelangelo’s David each year, few make it up to the second floor. This is a shame because there, in a large glass display case, you can see a very rare, astoundingly beautiful, and richly decorated embroidery from the 1300s.

This panel—more than 14 feet wide and 3 feet tall and embroidered with silk, gold, and silver threads—functioned as an altar frontal. That is, it once hung on the front (and perhaps the sides) of an altar (think of a table cloth, but only for the front and sides of the table). It was made for the important church of Santa Maria Novella, an enormous Dominican church in Florence. You may know this church if you’ve studied Italian art history since Masaccio’s The Holy Trinity is inside it, and the façade of the church was designed by the great Renaissance architect Alberti. Today the gold and silver thread is not nearly as lustrous as it was originally, and we are lucky to know the name of the embroiderer (since the work is signed)—Jacopo de Cambio. Given the richness of this altar frontal, it is likely that it decorated the altar only on special occasions, though we don’t know this for sure.

Jacopo de Cambio, Altar frontal on linen, embroidered in silk, silver, and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence) (photo: Bernhard Kvaal)

The subject

The large central scene on the altar frontal depicts the subject of the Coronation of the Virgin which depicts the Virgin Mary being crowned by Christ as queen of heaven following her Assumption into heaven at the end of her life. This event does not appear in the Bible, but became a common theme in Europe from the thirteenth century onward, reflecting Mary’s important role as the mother of Christ and as a heavenly intercessor on behalf of humanity. On either side are seven prophets and saints standing in niches (a total of fourteen) separated by slender columns. Above each column, in the spandrels, we see angels with their wings outstretched. They seem to be observing the heavenly scene, some with their hands in prayer, some with their hands folded over their chests. In the panel above the fringe (known as a super frontal), we see eleven scenes from the life of the Virgin alternating with twelve more prophets and saints in niches.

Spandrel with angel, and above birds with foliage and geometric patterns (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar front on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the horizontal bands just below the fringe, and at the bottom of the frontal, we see wonderfully lifelike birds, flowers, and leaves punctuated by geometric patterns.

Visitors who do make it to the second floor of the Accademia in Florence are often impressed with the altarpieces on display—large paintings (many with gold backgrounds) that once stood on or behind altars in churches and served as the backdrop for the priest during the sacrament of the Eucharist.

The Strozzi Chapel with Andrea Orcagna’s Strozzi Altarpiece, 1354–47 (Santa Maria Novella, Florence)

Altars and their decoration

Visiting the Strozzi Chapel in Santa Maria Novella (the church that our altar frontal was made for) gives you a sense of how these altarpieces originally appeared—standing atop altars in chapels that were themselves often decorated with fresco paintings. These chapels were often incredibly lavish spaces, with layers of decoration usually funded by one of the wealthy merchants of Florence (during this period and into the 15th century, Florence was one of the most commercial and wealthy cities in Europe). While many altarpieces survive (though most have been dispersed to museums and no longer in their original locations), what doesn’t survive as well are many of the portable decorative objects for the altar itself—especially textiles—and that’s why the altar frontal at the Accademia is so important—it gives us an idea of just how richly decorated altars could be.

Burse, central Italy, c. 1400-10, embroidered velvet, 20 x 20 cm (Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan)

Luxurious and portable items for use at altars could include a container (known as pyx) to hold the Eucharistic bread (which, according to Catholic belief, miraculously transformed into the body of Christ during the mass), a chalice for the Eucharistic wine (which miraculously transformed into the blood of Christ during the mass), and other kinds of containers such as the embroidered burse illustrated here (or this one made in England) which held the linen cloths used in the celebration of the mass and which, like the altar front for Santa Maria Novella, features an embroidered image of the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by musical angels. We also have to imagine candles and the beautifully embroidered garments—or “vestments”—often worn by priests to get a full picture of the visual richness of the apse and chapels in churches during a service (see, for example, this one in the Victoria and Albert Museum).

We write art’s history primarily from what survives, though historical sources can tell us quite a bit about what we’ve lost (due to the ravages of time, periods of upheaval, etc.), and in the case of textiles used for clothing, we can study their representation in paintings. Because of the nature of their materials, textiles are particularly susceptible to wear and tear, and very few survive from the 14th century. Even so, we know that Florence was an important center for the manufacture of textiles and was particularly famous for its embroidery, called opus florentinum (Florentine work). A bit earlier, England was the place to go for embroidery (opus anglicanum). Embroidery from England and Italy was so highly prized at this time (13–15th centuries) that the 1401 inventory of the possessions of Jean, duke of Berry, one of the wealthiest men in Europe (and a relation to several kings of France), describes more than fifteen Florentine embroideries. It’s easy to imagine that embroideries of the scale and workmanship of the one now seen in the Accademia would cost far more than many painted altarpieces.

Coronation of the Virgin with angels, and a saint on either side (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar front on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Coronation of the Virgin, saints, angels, birds, foliage, and more

Even from afar, we can see the central scene of the Coronation of the Virgin, a subject that was very popular in this period—especially in Florence. On either side of Christ and Mary are four angels. Three of the angels on either side play music (with a wind instrument, a string instrument, and a percussion instrument), and the kneeling angels in the foreground hold lilies, symbols of Mary’s purity.

Here, in heaven, Mary and Christ sit on a throne. Mary bows forward slightly so that Christ can place a crown on her head to make her queen. She crosses her arms modestly across her chest. Mary is dressed in an especially luxurious textile that draws our eye to her. The folds of the textile are indicated by using darker and lighter threads.

When we look closely at the central scene we see that the embroiderers left no surface unadorned. Just as the painters of the time used gold that was punched or inscribed to decorate the surface and create the impression of the heavenly status of the figures depicted, the embroiderer used a multitude of stitches, some flat, others raised.

The artist also applied separately embroidered pieces (like the crown) using a technique referred to as appliqué to the surface of the embroidery. Here the crown appears more substantial and stands out from rest of the embroidered fabric. Using this technique therefore allowed the artist to call attention to the crown and make it the focus on the composition. Christ and Mary also have more elaborately decorated halos, to indicate their special status.

This format—of a central narrative scene (such as the Coronation of the Virgin) surrounded by saints in niches—closely resembles the format of painted altarpieces (that would have stood above or behind the altar). There was a close relationship between paintings and embroideries, and painters often supplied the designs for the embroiderers. For example, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a drawing of an angel carrying lilies that served as the design for an embroidery.

Altarpiece made for the church of San Leo in Florence. Giovanni di Tano Fei, The Coronation of the Virgin, and Saints, 1394, tempera on wood, gold ground, 199.1 x 193 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

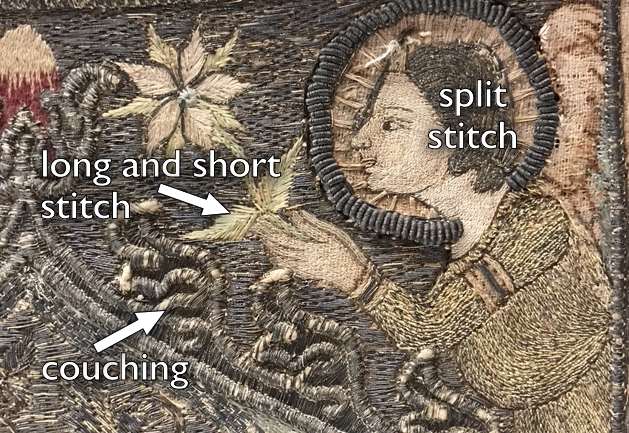

Only an expert in historical embroidery closely examining both the front and back of the fabric would be able to identify all the different stitches (though a few are more obvious even to novices).

This annotated image shows some of the different types of stitches that are used on the embroidery. Angel (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar front on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence)

Paintings of the Virgin Mary often featured a beautiful textile as a backdrop (referred to as the Cloth of Honor). We can see here that Jacopo de Cambio (the embroiderer) has created a background textile that features roundels containing various animals, and the round frames and the forms of the animals are slightly raised from the background. Of course, all this would have been much more visible and vibrant 700 years ago!

The Coronation of the Virgin Mary (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar front on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In both painting and embroidery, highly embellished textiles were used to communicate the special status of the saints and holy figures pictured. If we compare our embroidery to a painting of the same period (that shows the same subject), we can see the importance of textiles—and also of Mary’s crown.

Detail, Agnolo Gaddi, Coronation of the Virgin, c. 1380–85, egg tempera on wood, 183.6 x 94.3 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Musician angels

Let’s take a close look at two of the musician angels. The angels’ halos were made using a technique known as couching, where thicker threads are laid down on the surface and then attached to the fabric by threads (in this case of gold and silver).

Two musician angels (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar frontal on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The artist used light and dark threads on the faces of the figures, and on their drapery to indicate volume. The direction of the stitches creates the curls and waves in their hair, and a different kind of stitch creates the texture of feathers in the rightmost angel’s wings. And just as we see in painting of the period, the embroiderers used different tones to make the forms appear rounded and three dimensional. The fineness of the work is almost hard to conceive.

Nativity (detail), Jacopo de Cambio, Altar frontal on linen, embroidered in silk, silver and gold threads, signed and dated 1336, 106 x 440 cm (Accademia, Florence, photo Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nativity

In the Nativity, we see the newly born Christ held aloft by his mother and swaddled in cloth created with gold and silver thread. Joseph sits to the left, and angels fly above paying homage to the Christ child, just as animals do on the ground below him. On the far right, we see an angel instructing two shepherds that Christ was born.

Every inch is covered in stitches—we only see the background fabric where the embroidery has worn away, and embroidered decorative scrolling vines and leaves fill the space between the figures and animals. The naturalism of the figures and animals seems remarkable given that this is made of tiny stitches. The composition resembles paintings of the period (see for example Giotto’s Nativity and Adoration of the Shepherds from the Arena Chapel). There were standard ways that these frequently-represented subjects were represented—whether in painting or embroidery.

Survivors

Altar frontals could also be made of wood, and the Museu Episcopal de Vic and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya both hold large collections of these.

Coronation of the Virgin, side of the Altar from Santa Maria in Lluçà, 1210–20, tempera on poplar wood, 104.5 x 178.5 x 6 cm (Museu Episcopal de Vic)

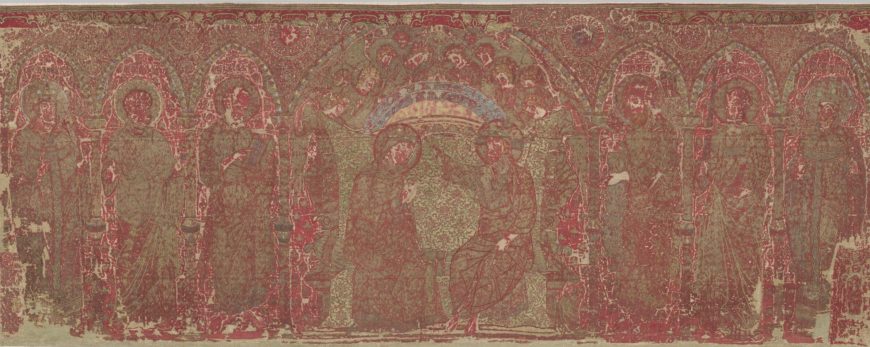

Though embroidered altar frontals from the 1300s that survive are very rare, there are a few others that are similar to the one in the Accademia today. The Veglia Altar Frontal in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London shows a remarkably similar composition, with the Coronation of the Virgin surrounded by angels in front of a Cloth of Honor, with saints in niches on either side.

The Veglia Altar Frontal, c. 1330, likely designed by Paolo Veneziano and made in Venice, red silk, in plain weave; with embroidery of gold and silver threads underside-couched, and with coloured silks, mainly in split stitch; interlined with paper and lined with linen. 107 x 277 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has one panel from many (they are now dispersed to different museums) of an embroidered altar frontal made by the workshop of a Florentine artist (Geri di Lapo) for the Cathedral in Manresa, Spain (1322–57). This piece of an embroidered altar frontal at The British Museum depicts Christ’s Charge to Peter and the Betrayal of Christ. Our embroidery in the Accademia in Florence is rare for its remarkable state of preservation.

These amazing survivors—now nearly 700 years old—teach us quite a bit about what we tend to call today the “minor” (decorative) arts, and how they were not at all minor all those centuries ago. A considerable amount of time, creative invention, and resources were clearly spent on this expensive altar frontal—unfortunately we don’t know how long and how much, or even the name of the patron. Nevertheless it’s a good reminder of all that we are missing when we see works of art on the walls of the museum, out of the context for which they were made.

Additional resources

Overview of embroidery from the Textile Research Centre

Making a medieval embroidery (includes a video) from the V&A

Video from Sarah Homfrey on Opus Anglicanum

The front of the Florentine altar or the front of the Passion (the most unknown treasure of Manresa)

Masterpieces of English Medieval Embroidery

Textiles and wealth in 14th Century Florence. wool, silk, painting (exhibition catalogue, Gallerie dell’Accademia, 2018).

English Medieval Embroidery, Opus Anglicanum, exhibition catalogue, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2016).

David van Fossen, “A Fourteenth-Century Embroidered Florentine Antependium,” The Art Bulletin vol. 50, no. 2 (June, 1968), pp. 141–52.

Anne E. Wardwell, “A Rare Florentine Embroidery of the Fourteenth Century”, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art vol. 66, no. 9 (Dec., 1979), pp. 322–33.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”cambi,”]