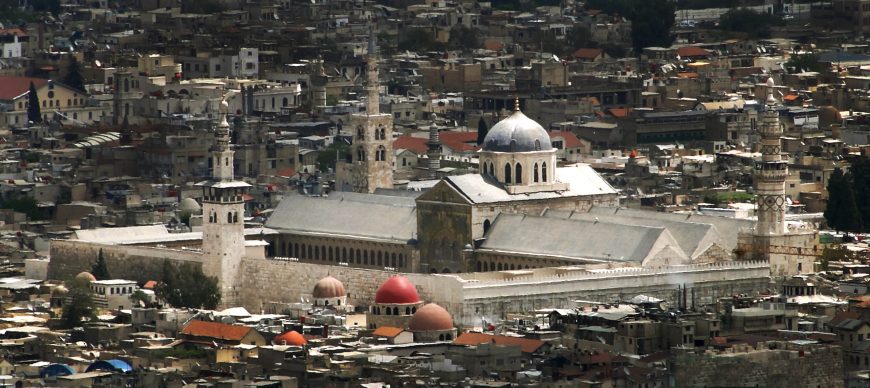

Distant view of the Great Mosque of Damascus (photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

To understand the importance of the Great Mosque of Damascus, built by the Umayyad caliph, al-Walid I between 708 and 715 C.E., we need to look into the recesses of time. Damascus is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world, with archaeological remains dating from as early as 9000 B.C.E., and sacred spaces have been central to the Old City of Damascus ever since. As early as the 9th century B.C.E., a temple was built to Hadad-Ramman, the Semitic god of storm and rain. Though the exact form and shape of this temple is unknown, a bas-relief with a sphinx, believed to come from this temple, was reused in the northern wall of the city’s Great Mosque.

From Zeus to Saul

Alexander the Great marched through Syria on his way to Persia and India and while he likely passed through Damascus, it was his successors—the Ptolemies and the Selecuids—who would shape Syria. Until 63 B.C.E., Damascus would remain under the political control and cultural influence of these Greek dynasties. While almost nothing survives archaeologically from this period, Greek became the dominant language and the culture became Hellenized (influenced by Greek culture). At this time, the temple of Hadad was converted into a Temple of Zeus-Hadad. Zeus was a natural choice for assimilation; he ruled the Greek pantheon and was associated with weather and, of course, thunder bolts. Many Greek (and later Roman) gods were combined with local gods across the lands controlled by the Greeks and then the Romans. This allowed the conquering culture to integrate their new subjects into their religion, while also accepting local traditions—thus helping to make new foreign masters more agreeable to subjugated locals. The Zeus-Hadad temple dominated the Greek city and was connected by a main thoroughfare to the new agora, or market area, located to the east. At the center of a temenos, an enclosed and sacred precinct, stood the temple to Zeus-Hadad, which had a cella (the room in which a statue of the god stood).

After the Greeks came the invading Roman armies (led by Pompey in 63 B.C.E.). Under Herod the Great (the local pro-Roman ruler), the city of Damascus was transformed. Herod built a theater whose remains can still be seen in the basement and ground floor of a house called Bayt al- ‘Aqqad (now the Danish Institute). The temple was modified at this time when two concentric walls were added to enclose the precinct (or peribolos) of the temple and two monumental gates, or propylaea, were added on the western and eastern ends of the precinct which now measured 117,000 square feet. At its center was the temple with a cella for the worship of Jupiter-Hadad. It was now a truly monumental temple. The western gate was refurbished and embellished under the Roman Severan dynasty, additions that remain visible today.

Although the great temple to Jupiter marked the spiritual heart of the city for several centuries, just as it was completed, a new cult to a single God was developing: Christianity. Saul, or Paul as he is known after his conversion, is said to have converted on the road to Damascus (Acts 9.1–2; 9.5–6). Blinded by a light, he was led to the home of a Jew named Judas on Straight Street, the decumanus or main east-west street in Damascus. Ananias had a vision that told him to go and care for Paul and when he touched Paul at Judas’ house, the scales fell from Paul’s eyes and he could see.

View of the exterior of the Great Mosque of Damascus in 2008 (photo: Ghaylam, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

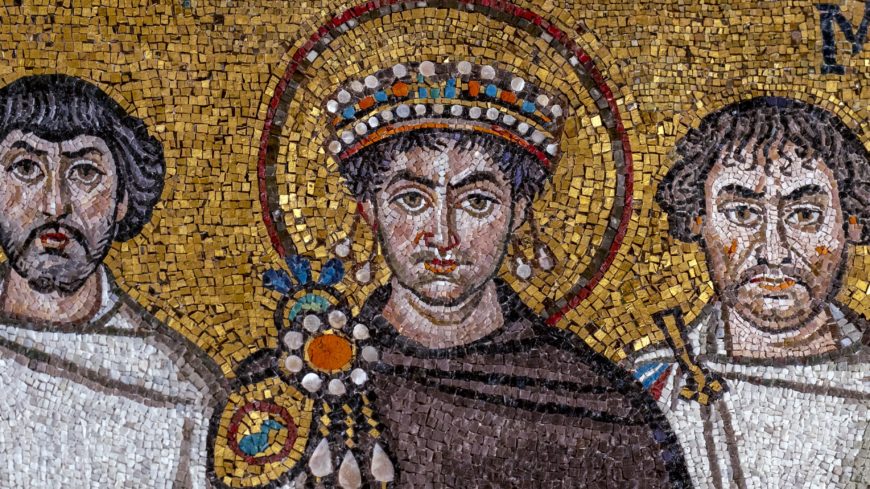

Unsurprisingly, once Christianity was widely adopted in the eastern part of the Roman Empire, the temple to Jupiter was once again converted, this time into a cathedral dedicated to John the Baptist. This church is attributed to the Emperor Theodosius in 391 C.E. The exact location of the church is unknown, but it is thought to have been located in the western part of the temenos. It was probably one of the largest churches in the Christian world and served as a major center of Christianity until 636 C.E. when the city was once again conquered, this time by Muslim Arabs. Damascus was a key city, as it provided access to the sea and to the desert. When it was clear that the city was going to fall, the defeated Christians and conquering Muslims negotiated the city’s surrender. The Muslims agreed to respect the lives, property and churches of the Christians. Christians retained control of their cathedral, although Muslim worshippers reportedly used the southern wall of the compound when they prayed towards Mecca.

View of the the prayer hall from the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus (treasury at right) (photo: Erik Shin, CC BY-NC 2.0)

al-Walid’s mosque

When Damascus became the capital of the Umayyad dynasty, the early 8th century caliph al-Walid envisioned a beautiful mosque at the heart of his new capital city, one that would rival any of the great religious buildings of the Christian world. The growing population of Muslims also required a large congregational mosque (a congregational mosque is a mosque where the community of believers, originally only men, would come to worship and hear a sermon on Fridays—it was typically the most important mosque in a city or in a neighborhood of a large city). The Great Mosque of Damascus was commissioned in 708 C.E. and was completed in 714/15 C.E. It was paid for with the state tax revenue raised over the course of seven years, a prodigious sum of money. The result of this investment was an architectural tour de force where mosaics and marbles created a truly awe-inspiring space. The Great Mosque of Damascus is one of the earliest surviving congregational mosques in the world. The mosque’s location and organization were directly influenced by the temples and the church that preceded it. It was built into the Roman temple wall and it reuses older building materials (called spolia by archaeologists) in its walls, including a beam with a Greek inscription that was originally part of the church.

Courtyard fountain and the dome of the clock in the distance, Great Mosque of Damascus (photo: Thom May, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The complex is composed of a prayer hall and a large open courtyard with a fountain for ablutions (washing) before prayer. Before the civil war that began in 2011, the courtyard of the mosque functioned as a social space for Damascenes, where families and friends could meet and talk while children chased each other through the colonnade, and where tourists once snapped photographs. It was a wonderful place of peace in a busy city. The courtyard contains an elevated treasury and a structure know as the “Dome of the Clock,” whose purpose is not fully understood. There are tower-like minarets at the corners of the mosque and courtyard; the southern minarets are built on the Roman-Byzantine corner towers and are probably the earliest minarets in Syria. Again, the earlier structures directly influenced the present form.

Prayer hall, Great Mosque of Damascus with the shrine of Saint John the Baptist in the center (photo: Seier+Seier, CC BY 2.0)

From the courtyard, one would enter the prayer hall. The prayer hall takes its form from Christian basilicas (which are in turn derived from ancient Roman law courts). However, there is no apse towards which one would pray. Rather the faithful pray facing the qibla wall. The qibla wall has a niche (mihrab), which focuses the faithful in their prayers. In line with the mihrab of the Great Mosque is a massive dome and a transept to accommodate a large number of worshippers. The façade of the transept facing the courtyard is decorated on the exterior with rich mosaics.

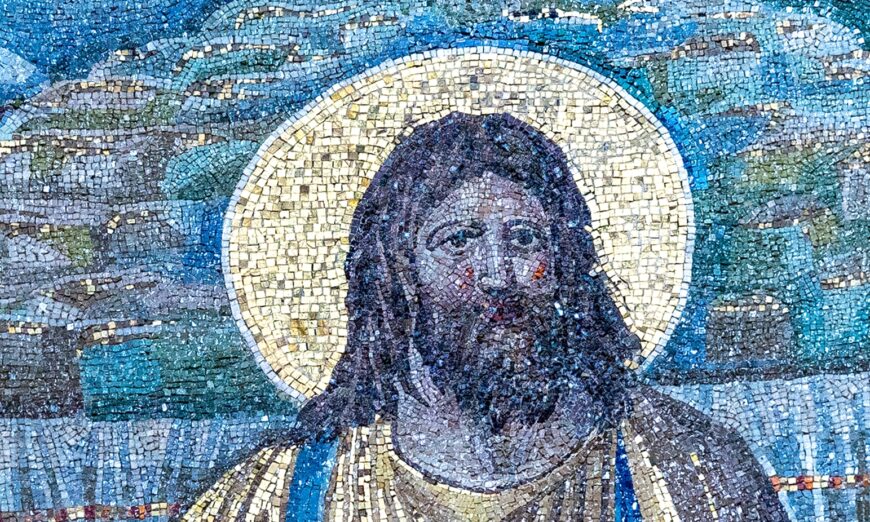

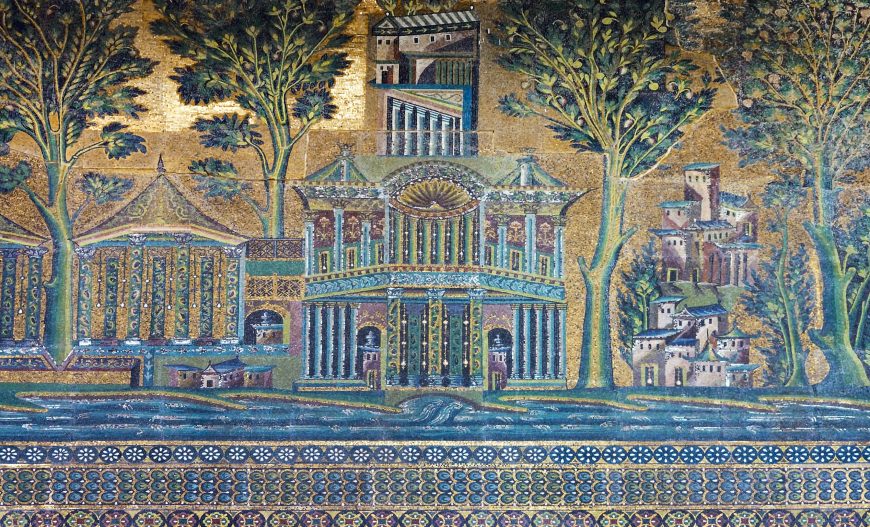

Mosaic, Great Mosque of Damascus, 8th century (photo: american rugbier, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although a fire in the 1890s badly damaged the courtyard and interior, much of the rich mosaic program, which dates primarily to the early 8th century, has survived. The mosaics are aniconic (non-figurative). Islamic religious art lacks figures, and so this is an early example of this tradition. The mosaics are a beautiful mix of trees, landscapes, and uninhabited architecture, rendered in stunning gold, greens, and blues. Later sources note that there were inscriptions and mosaics in the prayer hall, like the Umayyad mosque in Medina, but these have not survived.

Mediterranean influences

The architecture and the plants depicted in the mosaics have clear origins in the artistic traditions of the Mediterranean. Acanthus-like scrolls of greenery can be seen. Not only are they similar to those found in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, but similar motifs can be seen in the sculpture of the ancient Roman Ara Pacis.

Arches with acanthus motif in mosaic, Great Mosque of Damascus (photo: Judith McKenzie/Manar al-Athar, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There are other strong connections to the visual traditions of the Mediterranean world—to Ptolemaic architecture in Egypt, to the architecture of the Treasury at Petra, and the wall paintings of Pompeii. By using these well-established architectural and artistic forms, the Umayyads were coopting and transforming the artistic traditions of earlier, once dominant religions and empires. The use of such media and imagery allowed the new faith to assert its supremacy. The mosaics and architecture of the Great Mosque signaled this new prominence to an audience that was still predominantly Christian, that Islam was as powerful a religion as Christianity. The subject of the mosaics remains debated to this day, with scholars arguing that the mosaics either represent heaven, based on an interpretation of Quranic verse, or the local landscape (including the Barada River).

Scholars traditionally attributed the creation of these mosaics to artisans from Constantinople because a 12th century text claimed that the Byzantine emperor had sent mosaicists to Damascus. However, recent scholarship has challenged this as the text that made this claim was written from a Christian perspective and is much later than the mosaics. Scholars now think that the mosaics were either created by local artisans, or possibly by Egyptian artisans (since Egypt also has a long tradition of decorating domes with mosaics).

The influence of the mosque and its artistry can be seen as far as a way as Cordoba, Spain, where the 8th century Umayyad ruler, Abd al-Rahman (the only survivor of a massive family assassination that sparked the Abbasid Revolution), had fled. The mihrab and the dome above in the Great Mosque of Cordoba was decorated in blue, green and gold mosaics, evoking his lost Syrian homeland.

The Umayyad mosque of Damascus is truly one of the great mosques of the early Islamic world and it is remains one of the world’s most important monuments. Unlike many of Syria’s historic buildings and archaeological sites, the mosque has survived the Syrian Civil War relatively unscathed and hopefully, will one day again welcome Syrians and tourists alike.