A powerful Byzantine court official builds himself a dazzling burial chapel.

Chora church, Istanbul, renovated c. 1316–21

Christ Pantokrator mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An arresting, larger-than-life mosaic of Christ confronts viewers entering the Chora, a church that was once part of a monastery in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The bust-length Christ, who blesses viewers with his right hand and holds a jeweled Gospel book in his left hand, appears in the lunette above the door between the outer and inner narthex (view location in plan). Such depictions of Christ are commonly known as the “Pantokrator,” which means “almighty.” This mosaic is one of many well-preserved mosaics and frescoes in this church, which date to the fourteenth century.

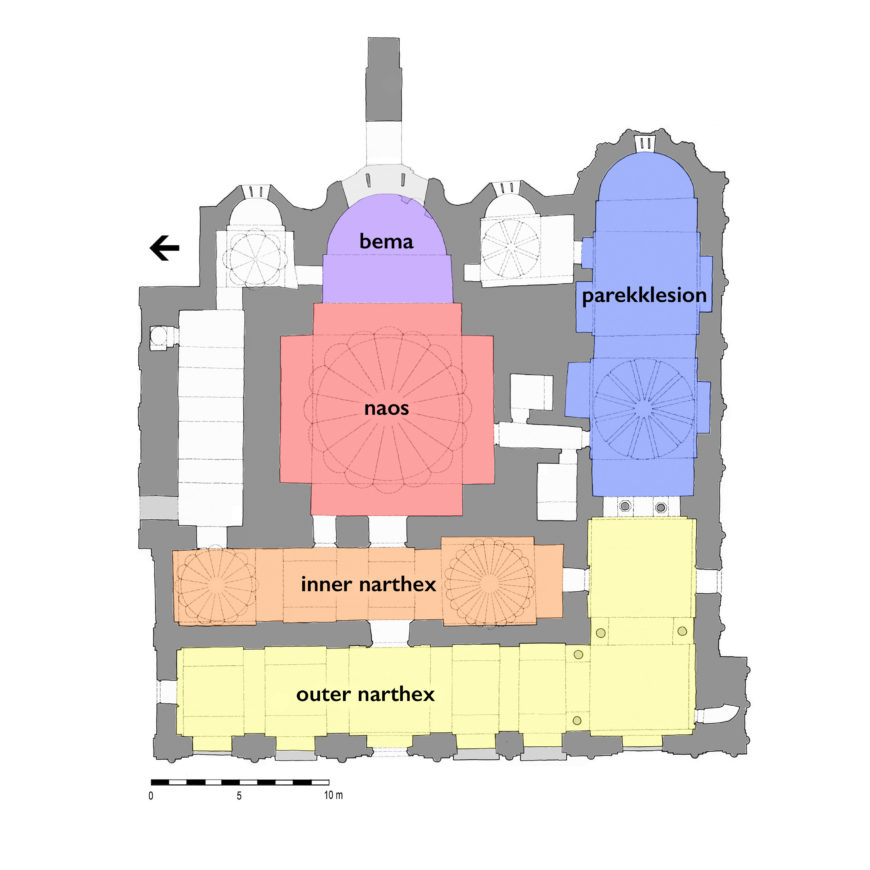

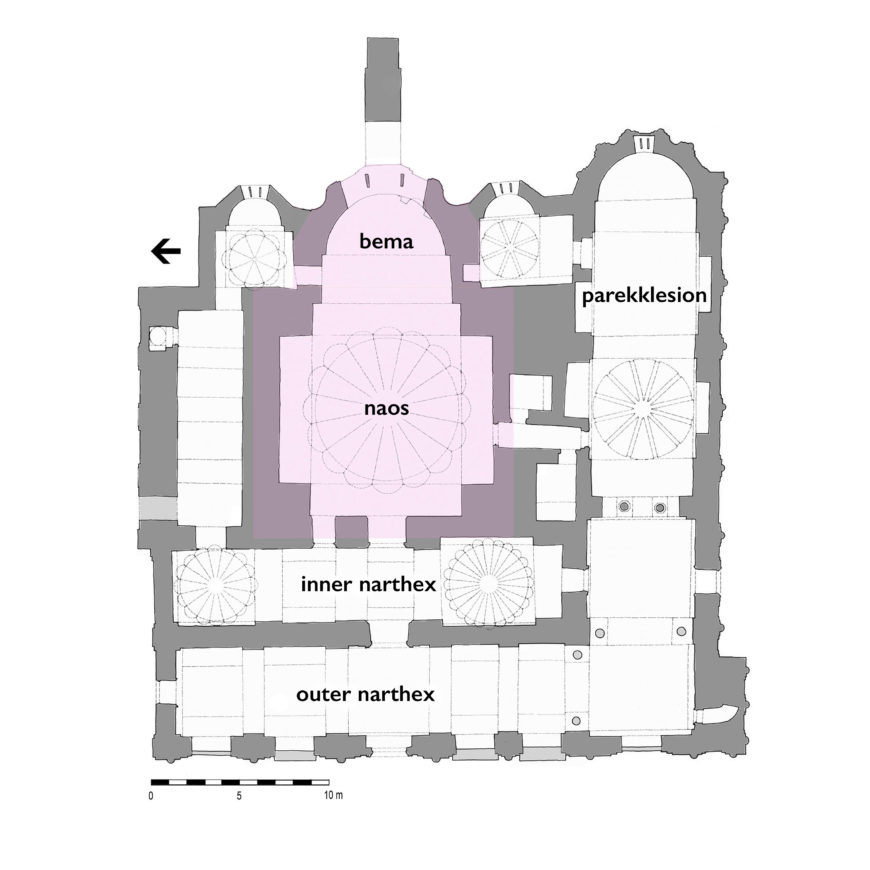

Chora church plan with the reused portions of the older naos highlighted in pink (© Robert G. Ousterhout)

Power and patronage

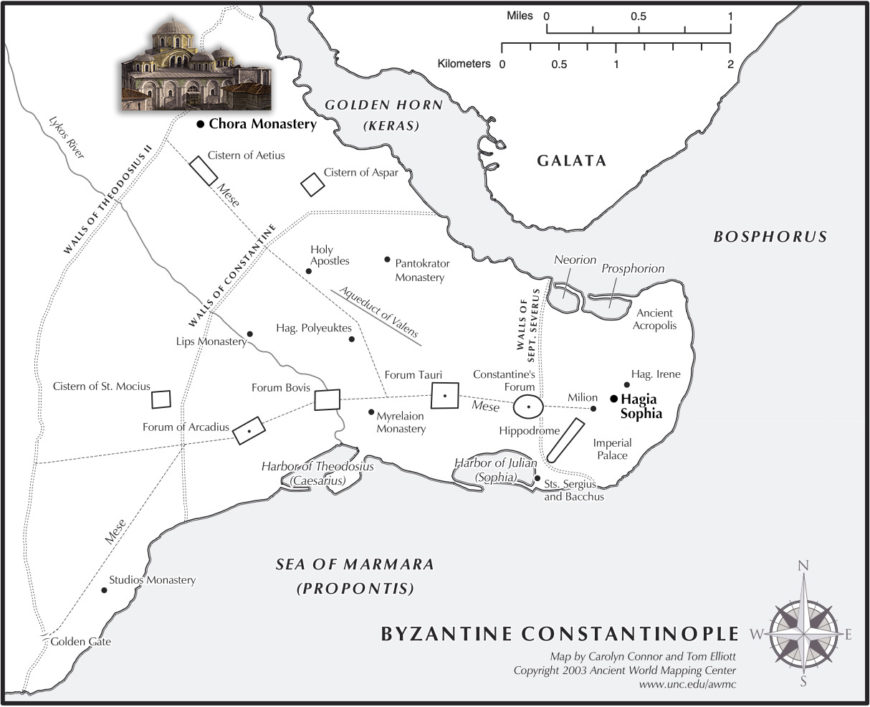

These mosaics and frescoes are the result of patronage by a wealthy intellectual and high-ranking official named Theodore Metochites, who restored the Chora c. 1316–1321, where he intended to be buried when he died. The early history of the Chora monastery is hazy, but the core of the current church was built in the twelfth century by Isaac Komnenos and fell into disrepair when Constantinople was sacked by western Europeans in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade.

About a century later, Metochites, a scholar of classical texts who donated his personal library to the Chora, held the position of Mesazon, or “prime minister,” to emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos, making him the second most powerful man in the empire. As ktetor (“founder,” or in this case, re-founder) of the Chora, Metochites oversaw the restoration of the twelfth-century church as well as the addition of inner and outer narthexes and a subsidiary chapel, or parekklesion, which served as a funeral chapel. The Chora’s rich mosaics and frescoes—among the finest examples of Late Byzantine art—illustrate Theodore Metochites’ ambition and his hope for salvation after death.

Christ Pantokrator mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Location of the Chora in the city of Constantinople (map: Carolyn Connor and Tom Elliot, Ancient World Mapping Center, CC BY-NC 3.0)

Jesus Christ, land of the living

Despite his seemingly stern gaze, the entrance mosaic of Christ Pantokrator is optimistically labeled “Jesus Christ, the land (chora) of the living,” a play on the monastery’s name, which likely originally referred to its location “in the country” outside of the city walls built by emperor Constantine. This phrase—“land of the living”—comes from Psalm 116:9: “I walk before the Lord in the land (chora) of the living.” [1] The same text from Psalm 116:9 also appears in the Orthodox funeral service, which would have taken place in the Chora’s funeral chapel. So, by labeling Christ “land of the living,” Metochites put a spiritual spin on the Monastery’s name while also expressing hope for eternal life within the church where he planned to be buried.

Virgin and Child mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mother of God, container of the uncontainable

This mosaic of Christ faces a mosaic on the opposite wall, which pictures the Virgin with hands raised in prayer and the Christ child over her torso as if in her womb (view location in plan). The Virgin is labeled: “Mother of God, container (chora) of the uncontainable (achoritou).” This phrase, which describes the paradox that a human (Mary) could contain the Son of God (Jesus) in her womb, similarly references the monastery’s name. Such prominent images of Christ and the Virgin in the Chora reflect their important role in the Christian story of salvation, as well as the fact that the Chora monastery and parekklesion were likely dedicated to the Virgin and the main church to Christ.

Theodore Metochites and Christ mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Theodore Metochites and Christ mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Donor image

Proceeding into the inner narthex, viewers encounter a mosaic of the patron himself, Theodore Metochites, in the lunette over the door to the main part of the church, or naos (view location in plan). Christ sits on a jeweled throne against an expansive gold ground. Metochites kneels to Christ’s right, dressed in extravagant garments and wearing a flamboyant, turban-like hat, the asymmetry of the composition emphasizing the interaction between the two figures. This mosaic suggests Theodore’s high position within the empire but also his submission to Christ. As was common in medieval donation scenes, Metochites offers a model of the Chora—the very church in which this mosaic is located—to Christ.

Deësis

To the right, on the eastern wall of the inner narthex, a monumental Deësis mosaic shows the Virgin asking Christ to have mercy on the world (view location in plan). Because of her important role as the Mother of God, the Byzantines viewed the Virgin as a powerful intercessor between Christ and the faithful. John the Baptist, often included in the Deësis, has been omitted, probably to maximize the scale of the image within the space. Two past patrons of the Chora kneel on either side: Isaac Komnenos and a nun labeled “Melanie, the Lady of the Mongols,” who may be the daughter of emperor Michael VIII.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Chora and Hagia Sophia

For Byzantine viewers, the image of Theodore Metochites would have called to mind two imperial images in Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia. Metochites’ gesture of donation evokes the tenth-century mosaic of Constantine and Justinian offering models of the city and Hagia Sophia to the Virgin and Child in the southwest vestibule. And Metochites’ kneeling gesture and position above the central door to the naos echoes the tenth-century mosaic of the prostrating emperor above Hagia Sophia’s “Imperial Door.”

Left: Chora’s donor mosaic; top right: Hagia Sophia’s southwest vestibule mosaic; bottom right: Hagia Sophia’s Imperial Door mosaic (photos, byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA)

The large scale of the Chora’s Deësis alludes to the monumental Deësis mosaic installed in Hagia Sophia’s south gallery—a section of the church reserved for imperial use—following the Latin crusaders’ occupation of Constantinople from 1204–1261. These visual echoes, or “intervisuality” between the Chora and Hagia Sophia, suggest Metochites’ desire to associate himself with Byzantium’s emperors, and his church with the capital’s cathedral, Hagia Sophia. [2]

Left: Chora’s Deësis (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Hagia Sophia’s Deësis (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Christ and the Virgin

Christ and the Virgin are the main subjects of the majority of the mosaics that fill the inner and outer narthexes. Narrative scenes from the lives of the Virgin and Christ adorn various architectural spaces, and often exhibit experimentation with figures and compositions.

Annunciation mosaic, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In a dynamic depiction of the Annunciation, the Virgin looks awkwardly over her shoulder as Gabriel approaches from above. The image responds to the triangular architectural surface in which it is situated, resulting in an unconventional, diagonal composition.

The Virgin with her parents, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An image of the Virgin Mary with her parents exhibits a remarkable intimacy and evokes everyday life. Such “everyday” images in the Chora challenge common generalizations about Byzantine art as distant, spiritualized, and otherworldly.

South pumpkin dome, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Detail of north pumpkin dome, c. 1316–1321, inner narthex, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The mosaics of the inner narthex culminate with two pumpkin domes (named for their fluted shape that resembles the undulating surface of a pumpkin) that display mosaics of Christ and the Virgin surrounded by their saintly ancestors from scripture (view location in plan).

Within the Chora, all human history seems to point toward these two figures and the pivotal role they play in the salvation of humankind.

The main church

Dormition mosaic, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: © thebyzantinelegacy)

Only three mosaics survive in the main church today. A mosaic of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary appears on the back (western) wall of the naos. And pair of proskynetaria icons of Christ and the Virgin once flanked the templon (the barrier between the sanctuary and naos, which no longer survives). These three images indicate that the emphasis on Christ and the Virgin that began in the narthexes continued in the main church where the Eucharist was celebrated.

Proskynetaria icons, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: © thebyzantinelegacy)

The Parekklesion

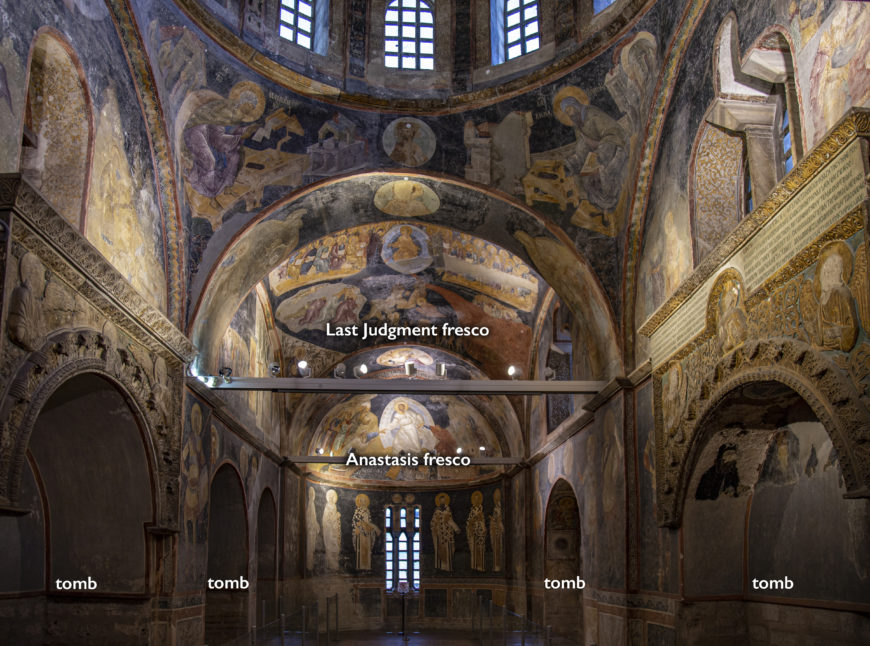

Better preserved are the frescoes in the parekklesion (side chapel), located to the south of the main church, which present a message of salvation that is fitting for this funeral chapel. Arcosolia (arched recesses for tombs) punctuate the walls and were intended for the burial of Metochites and his loved ones (view location of tombs in plan).

Parekklesion dome, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Warrior saint seem to guard the arcosolia, c. 1316–1321, parekklesion, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One enters the parekklesion beneath a dome decorated with frescoes of the Virgin and Child surrounded by angels (view location in plan). Hymnographers appear in the pendentives beneath the dome. Further below are scenes from the Old Testament, including Jacob’s ladder, Jacob wrestling the angel, Moses and the burning bush, scenes with the Ark of the Covenant, and more, which were understood as “types” of Christ and the Virgin. In other words, the Byzantines believed these episodes from the Old Testament prefigured Christ’s salvation of humankind. At ground level, soldier saints surround the tombs, brandishing their weapons like sacred guardians over the dead.

Last Judgment fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Judgment and Resurrection

Proceeding further into the parekklesion, the viewer passes under a sprawling image of the Last Judgment, sobering but also hopeful, since it depicts the damnation but also the salvation of souls (view location in plan). The parekklesion frescoes culminate at the east end with images of resurrection, reflecting the Christian belief that God will raise the dead at the end of time.

Anastasis fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Parekklesion, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The focal point of the parekklesion is the Anastasis (“resurrection”) fresco in the apse (view location in plan). The voluminous garments on the figures in this scene are a hallmark of Late Byzantine art. Drawn from non-biblical texts, the Anastasis visualizes Christ descending into Hades (the underworld) following his crucifixion to free human souls from the captivity of death. Christ’s death on the cross has paradoxically made him a victor over death, as described in the Orthodox hymn for Pascha (Easter): “Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life!” Clad entirely in white, Christ strides dynamically over the broken locks and doors of the underworld, and a personification of Hades lies bound and defeated at the bottom of the composition. Adam and Eve—the archetypal first humans responsible for bringing sin and death into the world—are forcefully pulled from their tombs by the risen Christ.

Detail of Anastasis fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Hope for salvation

Despite his considerable learning and political ambition, Metochites remained mindful of his mortality as he rebuilt the Chora monastery. While his donor image clearly communicated his position and achievements to all who entered the church, the frescoes of the parekklesion speak to Metochites’ anticipation of God’s judgment and his hope for resurrection and eternal life in the chora, or land, of the living.