A mosaic proclaims Christ’s rule over the Heavenly Jerusalem. Gesture, toga, and book signal imperial authority.

Apse mosaic in Santa Pudenziana, c. 400 (Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:09] We’re standing in the oldest surviving Christian space in all of Rome. This is Santa Pudenziana.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:16] Like all churches in Rome, this church is an agglomeration of different times and different periods and different styles, but the part that interests us most today is the mosaic that’s in the apse. In the early 300s, Constantine had allowed freedom of worship for Christians, but Christianity really takes hold in Rome in the 400s.

Dr. Zucker: [0:33] It is extraordinary that a mosaic has survived for 1700 years.

Dr. Harris: [0:39] Well, it’s been heavily restored and also cut down.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] Nevertheless, we see images that are in this critical transitional moment between the ancient Roman pagan traditions, the polytheistic traditions of naturalism, and this moment when Christian art is first developing.

Dr. Harris: [1:02] What we see here in the center is Christ himself on a throne with a halo. He sits below an enormous cross. It’s encrusted with jewels. On either side of that are the beasts that are mentioned in the Book of Revelation.

Dr. Zucker: [1:11] This is a scene of the heavenly Jerusalem, of Paradise. Christ is represented almost as if he were an imperial authority. Almost as if he were an emperor.

Dr. Harris: [1:27] This church is in fact a Roman basilica that was adapted to become a church. The apse, the semicircular space at the end, might be the place where the emperor sat, or a judge sat. So it makes sense that we have an image of Christ here in the apse.

Dr. Zucker: [1:37] He’s surrounded by the apostles and by two female personifications, each of which are crowning Peter and Paul respectively. But I’m fascinated by the architecture that surrounds them. We see Roman architecture, but in an idealized city, an idealized Jerusalem.

Dr. Harris: [1:53] In the early centuries of Christianity, the focus turns to Jerusalem, where Christ preached, and also to the city of Bethlehem, where he was born. And so we have this image of Jerusalem as Paradise, as this place where we have eternal life through Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [2:19] Look at the way Christ gleams. This golden glass tesserae reflecting the light coming in from the dome above. He sparkles, he seems as if he is heavenly. And incorporeal, as if his body is not solid but seems to be some kind of magical light.

Dr. Harris: [2:35] The figures that surround him, although restored, look like classical figures. They look like ancient Roman senators in their clothing, in their faces, which are so individualized.

Dr. Zucker: [2:41] It is extraordinary to me that we can sit here and look at an image that somebody in the 4th century saw.

Dr. Harris: [2:48] Christ enthroned in the center with a gold halo behind him, gesturing to the right, but above him, this enormous cross, that’s as big or bigger than he is, surrounded by these beasts from the Book of Revelation.

[3:03] So this clear idea of the end of time, of salvation, of the second coming of Christ, of a paradise that is achievable through Christ.

[0:00] [music]

Façade of Santa Pudenziana, 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A ritual space

The opulent interior of the Constantinian basilicas would have created an effective space for increasingly elaborate rituals. Influenced by the splendor of the rituals associated with the emperor, the liturgy placed emphasis on the dramatic entrances and the stages of the rituals. For example, the introit or entrance of the priest into the church was influenced by the adventus or arrival of the emperor.

Nave and apse of Santa Pudenziana, 4th century C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The culmination of the entrance, as well as the focal point of the architecture, was the apse. It was here that the sacraments would be performed, and it was here that the priest would proclaim the word. In Roman civic and imperial basilicas, the apse had been the seat of authority. In the civic basilicas, this is where the magistrate would sit adjacent to an imperial image and dispense judgment. In the imperial basilicas, the emperor would be enthroned. These associations with authority made the apse a suitable stage for the Christian rituals. The priest would be like the magistrate proclaiming the word of a higher authority.

A late 4th century mosaic in the apse of the Roman church of Santa Pudenziana visualizes this. We see in this image a dramatic transformation in the conception of Christ from the pre-Constantinian period.

Apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana, 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Missorium of Theodosius, 388 C.E., silver with traces of gilding, 74 cm diameter (Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid)

From teacher to God

In the Santa Pudenziana mosaic, Christ is shown in the center, seated on a jewel-encrusted throne. He wears a gold toga with purple trim, both colors associated with imperial authority. His right hand is extended in the ad locutio gesture conventional in imperial representations. Holding a book in his right hand, Christ is shown proclaiming the word. This is dependent on another convention of Roman imperial art of the so-called traditio legis, or the handing down of the law. A silver plate known as the Missorium of Theodosius made for the Emperor Theodosius in 388 to mark the tenth anniversary of his accession to power shows the Emperor in the center handing down the scroll of the law. Notably, the Emperor Theodosius is shown with a halo, much like the figure of Christ.

Christ proclaiming the word (detail), apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana, 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the halo would become a standard convention in Christian art to demarcate sacred figures, the origins of this convention can be found in imperial representations like the image of Theodosius. Behind the figure of Christ appears an elaborate city. In the center appears a hill surmounted by a jewel-encrusted Cross. This identifies the city as Jerusalem and the hill as Golgotha, but this is not the earthly city but rather the heavenly Jerusalem. This is made clear by the four figures seen hovering in the sky around the Cross. These are identifiable as the four beasts that are described as accompanying the lamb in the Book of Revelation.

Winged lion representing St. Mark and winged ox representing St. Luke, two of the Four Evangelists (detail), apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana, 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The winged man, the winged lion, the winged ox, and the eagle became in Christian art symbols for the Four Evangelists, but in the context of the Santa Pudenziana mosaic, they define the realm as outside earthly time and space or as the heavenly realm. Christ is thus represented as the ruler of the heavenly city. The cross has become a sign of the triumph of Christ. This mosaic finds a clear echo in the following excerpt from the writings of the early Christian theologian St. John Chrysostom:

You will see the king, seated on the throne of that unutterable glory, together with the angels and archangels standing beside him, as well as the countless legions of the ranks of the saints. This is how the Holy City appears….In this city is towering the wonderful and glorious sign of victory, the Cross, the victory booty of Christ, the first fruit of our human kind, the spoils of war of our king.

Migne, PG, LVII, cols. 23–24

The language of this passage shows the unmistakable influence of the Roman emphasis on triumph. The cross is characterized as a trophy or victory monument. Christ is conceived of as a warrior king. The order of the heavenly realm is characterized as like the Roman army divided up into legions. Both the text and mosaic reflect the transformation in the conception of Christ. These document the merging of Christianity with Roman imperial authority.

Christ and the Apostles, Catacombs of Domitilla, 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Tyler Bell, CC BY 2.0)

It is this aura of imperial authority that distinguishes the Santa Pudenziana mosaic from the painting of Christ and his disciples from the Catacomb of Domitilla. Christ in the catacomb painting is simply a teacher, while in the mosaic, Christ has been transformed into the ruler of heaven. Even his long flowing beard and hair construct Christ as being like Zeus or Jupiter. The mosaic makes clear that all authority comes from Christ. He delegates that authority to his flanking apostles. It is significant that in the Santa Pudenziana mosaic, the figure of Christ is flanked by the figure of St. Paul on the left and the figure of St. Peter on the right. These are the principal apostles.

Female figure personifying the division of the church of the Jews and the Gentiles (detail), apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana (detail), 4th century C.E., Rome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

By the 4th century, it was already established that the Bishop of Rome, or the Pope, was the successor of St. Peter, the founder of the Church of Rome. Just as power descends from Christ through the apostles, so at the end of time, that power will be returned to Christ. The standing female figures can be identified as personifications of the major division of Christianity between the church of the Jews and that of the Gentiles. They can be seen as offering up their crowns to Christ, like the 24 Elders are described as returning their crowns in the Book of Revelation.

Missorium of Theodosius, 388 C.E., silver with traces of gilding, 74 cm diameter (Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid)

The meaning is clear that all authority comes from Christ, just as in the Missorium of Theodosius, which shows the transmission of authority from the Emperor to his co-emperors. This emphasis on authority should be understood in the context of the religious debates of the period. When Constantine accepted Christianity, there was not one Christianity but a wide diversity of different versions. A central concern for Constantine was the establishment of Christian orthodoxy in order to unify the church.

Christianity underwent a fundamental transformation with its acceptance by Constantine. The imagery of Christian art before Constantine appealed to the believer’s desires for personal salvation, while the dominant themes of Christian art after Constantine emphasized the authority of Christ and His church in the world.

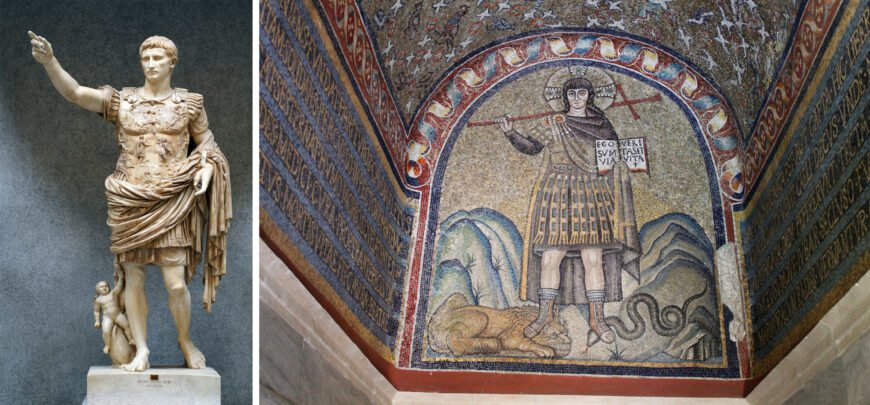

Statue of Roman Emperor Augustus, wearing a cuirass, and a mosaic of Christ depicted in a similar manner. Left: Augustus of Primaporta, early 1st century C.E., marble with traces of polychromy, 203 cm high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Christ treading the Lion and Asp mosaic from the Archiepiscopal Palace, 5th century C.E. (Archiepiscopal Palace, Ravenna; photo: Incola, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Just as Rome became Christian, Christianity and Christ took on the aura of Imperial Rome. A dramatic example of this is presented by a mosaic of Christ in the Archiepiscopal Palace in Ravenna. Here Christ is shown wearing the cuirass, or the breastplate, regularly depicted in images of Roman Emperors and generals. The staff of imperial authority has been transformed into the cross.