Icons: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 35

Byzantine architecture and monumental art after iconoclasm

Virgin orans apse mosaic, St. Sophia, Kyiv, begun 1037 (photo: CC0)

A golden mosaic of the Virgin Mary soars in the apse of the church of St. Sophia in Kyiv, Ukraine, measuring some 5.5 meters (18 feet) tall. She lifts her hands in an orans gesture of prayer that recalls some of the oldest Christian artworks, while a Greek inscription identifies her as the “Mother of God” in the manner of the religious images, or “icons,” of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire whose capital was Constantinople.

Map of Kyivan Rus’ and the “Byzantine” Empire (underlying map © Google)

But Kyiv was not part of the Eastern Roman Empire; in the eleventh century when this mosaic was produced, Kyiv was the capital of a powerful confederation of city-states known as Kyivan Rus’. The mosaic was likely a product of collaboration between imported Eastern Roman and local Rus’ artisans.

Solidus of Leo VI, 886–908, Constantinople, gold, 4.37g (photo © Dumbarton Oaks)

The mosaic echoes similar images installed in churches and the palace in the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople following the eighth- and ninth-century Iconoclastic Controversy over religious images. These mosaic images in Constantinople no longer survive, although the same image of the Virgin appears on Eastern Roman coins from the same period. So, St. Sophia’s Virgin orans mosaic illustrates how Kyivan Rus’ adapted Eastern Roman art in a period when they allied themselves with Constantinople and sought to adopt the religion and emulate the powerful empire of the Eastern Romans.

This chapter explores the monumental art and architecture of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire from the end of the Iconoclastic Controversy—a debate over the role of images (discussed more below)—in 843 to the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. It also considers the ways that Eastern Roman art and architecture influenced neighboring cultures, such as Kyivan Rus’ and Norman Sicily.

A triumph of images

In 330 C.E., emperor Constantine established Constantinople (Istanbul) as a new capital of the Roman Empire (supplanting Rome, Italy). While the city of Rome increasingly faced incursions from Germanic invaders from the north, the Roman state, or “Eastern Roman Empire,” continued to flourish from its new capital of Constantinople for centuries. But a controversy erupted in Constantinople in the 700s over the use of religious images, or icons, and whether they should be used in Christian worship or banned. For the Eastern Romans, the stakes of the debate were high for both religious belief and the fate of their empire. The definitive victory of the pro-image iconophiles and the affirmation of icons in 843—which became known as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy”—inaugurated what historians refer to as the Middle Byzantine period and set the trajectory for the history of art in the Eastern Roman Empire and beyond for centuries to come.

Apse mosaic depicting the Virgin and Child, dedicated 867, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Although Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia, did not originally display figural imagery, the iconophiles now installed a monumental mosaic of the Virgin Mary and Christ child in the eastern apse accompanied by a triumphant inscription: “The images which the imposters had cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” Hagia Sophia continued to accumulate new mosaic images of Christ, saints, and angels, as well as historic and even living emperors in the centuries that followed, reflecting the enduring power of images in the Eastern Roman Empire.

Read essays about the triumph of images

A work in progress: After the Iconoclastic Controversy, new mosaic images were installed in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Middle Byzantine mosaics and frescoes

Daphni monastery, Chaidari, c. 1050–1150 (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

After iconoclasm, new churches continued to elaborate on the domed architecture developed in the pre-Iconoclastic (Early Byzantine) period—exemplified by Justinian’s sixth-century Hagia Sophia—though they were built on a smaller scale. With the end of Iconoclasm and affirmation of icons, Eastern Roman art and architecture now developed in tandem: new churches were built to accommodate extensive decoration with images, and mosaics and frescoes were deployed to fit the many curved and angled surfaces of church interiors.

St. Joachim, 11th century, mosaic, narthex, katholikon, Nea Moni, Chios (photo: Marmontel, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The integration of monumental art and domed architecture can be observed in the churches of Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni, all located in Greece and decorated with mosaic icons, as well as with the church of St. Panteleimon at Nerezi, North Macedonia, which is adorned with frescoes.

Left: Mosaic depicting the Presentation of Christ in the Temple at Hosios Loukas (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: Masaccio’s Holy Trinity fresco at Santa Maria Novella (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Rather than seeking to create the illusion of a pictorial space, as in some Italian renaissance artworks like Masaccio’s Holy Trinity in Florence, the figures in Middle Byzantine mosaics—like this depiction of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple at Hosios Loukas—often appear against a gold ground and seem to communicate with one another across the walls of the church, giving the impression that they occupy the same space as the viewer.

Left:Lamentation fresco, 1164, Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Giotto, Lamentation fresco, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, 1305–06, Padua (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the dramatic frescoes at Nerezi, figures are set within colorful landscapes and express human emotions in a way that anticipates later paintings like those by Giotto in the Arena Chapel in Padua.

Read essays about Middle Byzantine mosaics and frescoes

Middle Byzantine church architecture: After the Iconoclastic Controversy, churches were designed to be decorated with monumental images.

Read Now >

Mosaics and microcosm: A focus on the monasteries of Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni.

Read Now >

Byzantine frescoes at Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi: With vivid colors and graceful lines, Nerezi’s frescoes depict elongated figures that exhibit a range of emotions and sometimes occupy naturalistic landscapes.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Building beyond Byzantium

Kingdom of Norman Sicily c. 1154 (underlying map © Google)

The Mediterranean was a crossroads of trade, diplomacy, and other forms of cross-cultural exchange in the medieval period, as seen in the mobility of luxury materials and portable objects during this time. The architecture and monumental art of the powerful East Roman Empire became an object of emulation in neighboring lands, such as Kyivan Rus’ and Norman Sicily in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Appropriating Eastern Roman art and architecture enabled neighboring peoples to associate themselves with the Roman capital of Constantinople and to project their own power and legitimacy with the recognizable visual vocabulary of the Eastern Romans.

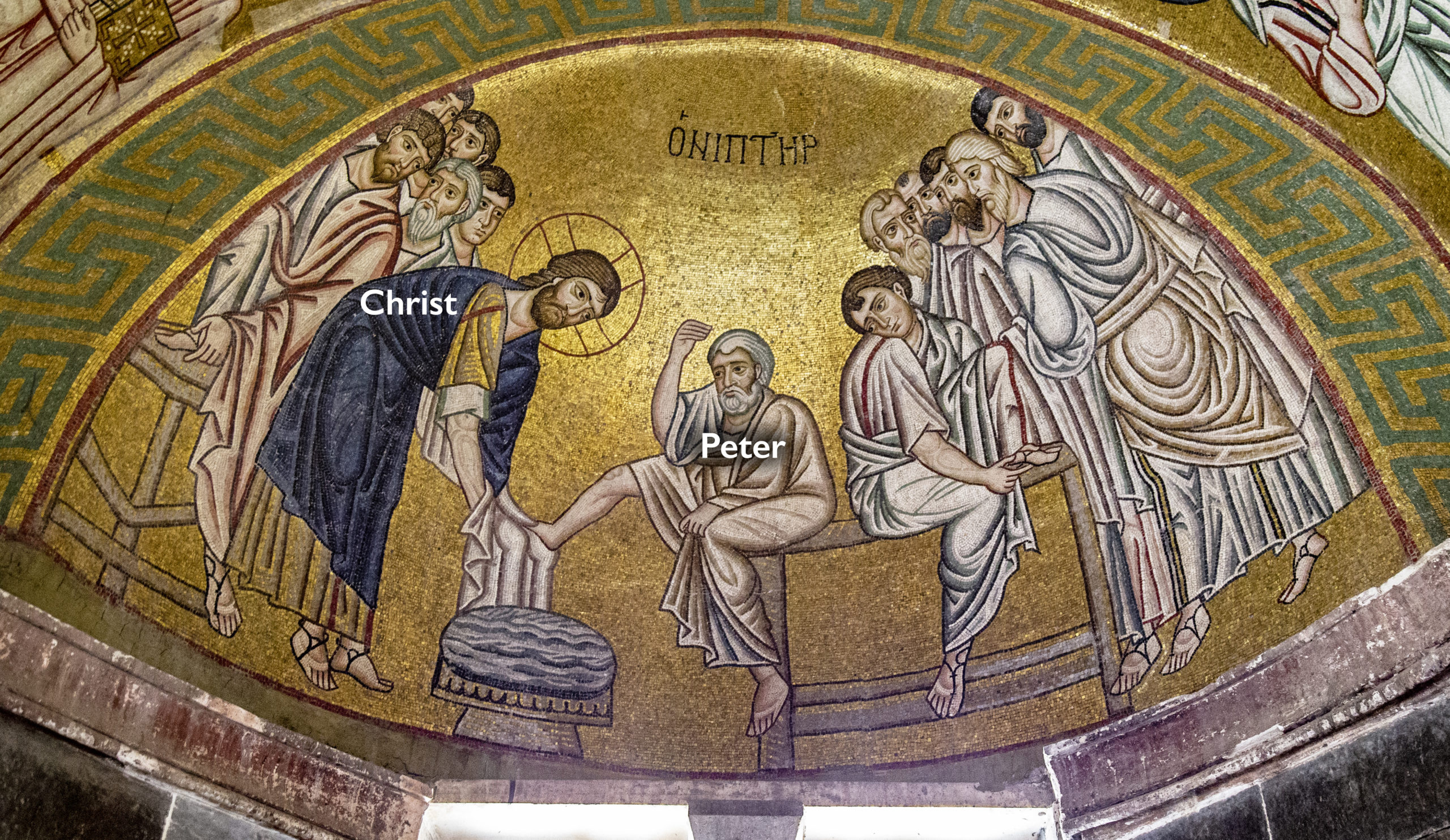

Christ Pantokrator surrounded by angels, and below apostles and the four evangelists, Dome mosaics, St. Sophia, Kyiv, begun 1037 (photo © Archimandrite Seraphim)

Kyivan Rus’ emerged in the second half of the ninth century as a powerful confederation of city states whose capital was Kyiv (Ukraine). They engaged in trade and raiding, attacking Eastern Roman territories and cities, including Constantinople itself. But in 987 Prince Vladimir I of Kyiv formed an alliance with the Eastern Roman emperor Basil II, converting to Christianity and marrying Basil’s sister Anna in 988. Vladimir also established the Christianity of the Eastern Romans as the state religion of Rus’ as well. Vladimir’s son, Prince Yaroslav “the Wise,” expanded his capital city of Kyiv in imitation of the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople. His new cathedral, St. Sophia, took the form of an expanded Middle Byzantine church and was decorated with Byzantine-style mosaics—including the monumental Virgin orans in its apse—as well as frescoes.

Interior of the Cappella Palatina looking west, c. 1130–43, Palermo (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the late eleventh century, Normans took control of Sicily in southern Italy, which had previously been governed by the Eastern Romans and Islamic rulers. The palace chapel of King Roger II, known as the Cappella Palatina (built c. 1130–43), combined Romanesque architecture, Byzantine-style mosaics, and an Islamic-style muqarnas ceiling. The Normans deployed this eclectic synthesis of different cultural traditions to project authority over their multiethnic kingdom and throughout the wider medieval Mediterranean.

Read essays about art and architecture beyond Byzantium

Byzantium, Kyivan Rus’, and their contested legacies: Icons and architecture tell the story of the Byzantine Empire and Kyivan Rus’—two medieval states whose legacies are still contested today

Read Now >

The Cappella Palatina: Drawing from both Christian and Islamic artistic traditions, the Norman King Roger II built the Cappella Palatina to be his dazzling palace chapel and royal ceremonial hall.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The Fourth Crusade

In 1204, western European crusaders of the Fourth Crusade veered from their path toward Jerusalem and instead sacked, looted, and occupied the Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople. It was probably during this period that Hagia Sophia acquired flying buttresses and a belfry: hallmarks of western European rather than Eastern Roman architecture. Displaced from their capital, the Eastern Romans established three successor states: the Despotate of Epirus (located in what is today northwest Greece and Albania), the Empire of Nicaea (located in northwest Anatolia in what is today Turkey), and the Empire of Trebizond on the southern coast of the Black Sea (located in northeast Anatolia in what is today Turkey). Although the Fourth Crusade was devastating for the Eastern Roman Empire, it also facilitated cross-cultural encounters between Eastern Roman, crusader, and other local communities, which is reflected in new architecture of the period. The looting of Constantinople also brought an influx of artistic and religious treasures to western Europe, as seen, for example, at the church and treasury of San Marco in Venice.

Read essays and watch a video about the Fourth Crusade

/3 Completed

Rebuilding Constantinople

In 1261, the Empire of Nicaea reclaimed Constantinople from the occupying crusaders and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as emperor, inaugurating what historians refer to as the Late Byzantine period. Constantinople had fallen into disrepair during its crusader occupation and the Eastern Romans now embarked on a flurry of rebuilding, which has sometimes been described as a “Palaiologan renaissance.”

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos is likely responsible for installing a new monumental mosaic of the Deësis in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia, an area of the church traditionally reserved for imperial use. The Deësis pictures the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist asking Christ to have mercy on humankind, and must have been particularly poignant as the Eastern Romans sought to rebuild their empire following the devastation of the Fourth Crusade. The mosaic suggests an interest in anatomical accuracy and the modeling of form, paralleling similar trends in Italian art around the same time, which have been associated with the beginnings of the Italian renaissance.

Anastasis fresco, c. 1316–21, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Theodore Metochites, an Eastern Roman intellectual and statesman renovated, expanded, and redecorated the Chora monastery—located in the northwestern part of Constantinople—where he intended to be buried. The monastery had fallen into disrepair during the period of crusader occupation, perhaps as a result of earthquakes, and Eastern Roman sources complain about its state of decay. Metochites adorned the Chora’s expanded double narthex with mosaic scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin and a small funeral chapel, or parekklesion, south of the main church with fresco images of judgment and resurrection.

Soldier saints seem to guard the tombs, c. 1316–21, parekklesion, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Frescoes of soldier saints brandishing weapons seem to guard the tombs in the parekklesion and must have offered a sense of divine protection in this time of instability and uncertainty that followed the Fourth Crusade. Metochites’ renovated Chora monastery is emblematic of the creativity and complexity of Eastern Roman art and architecture in the Late Byzantine period, at the same time as the empire’s boundaries continued to shrink before Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453.

Watch a video and read essays about rebuilding Constantinople

Late Byzantine church architecture: some of Byzantium’s most beautiful churches date from the last days of the empire.

Read Now >

/3 Completed

Eastern Roman afterlives

Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul—designed by Mimar Sinan and inaugurated 1557—was influenced by Byzantine architecture (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Soon after the Ottomans conquered Constantinople and brought the long history of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire to an end, they transformed the city’s Great Church, Hagia Sophia, into a mosque. Other churches were razed, although the subsequent history of Ottoman architecture reveals the enduring influence of Eastern Roman structures like Hagia Sophia, as we see with the Süleymaniye Mosque.

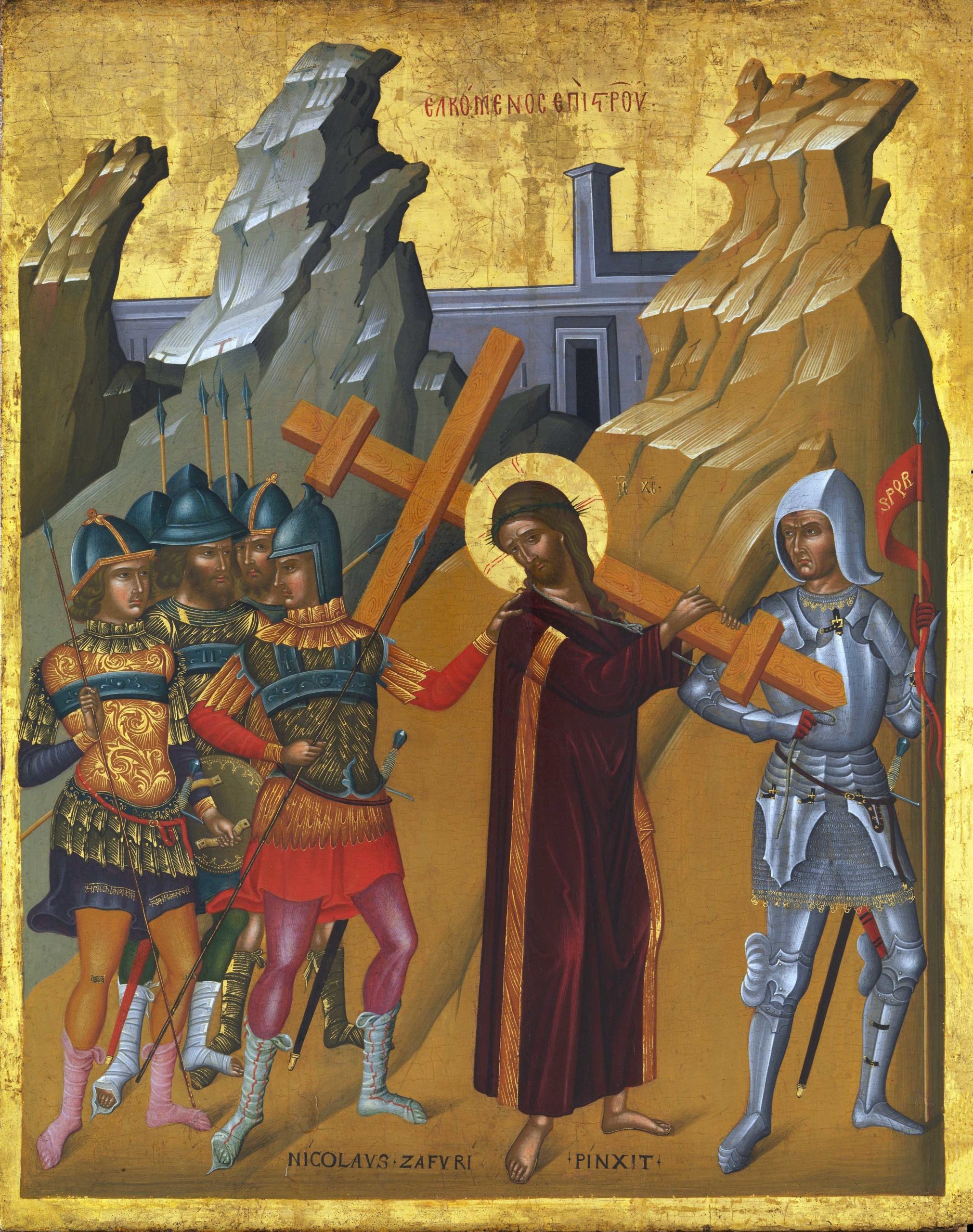

Nicolaos Tzafouris, Christ Bearing the Cross, late 1400s, oil on tempera and gold ground, 69.2 x 54.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Within the Ottoman Empire, Orthodox Christians continued to create art in the Eastern Roman tradition even after their empire had ended while also being influenced by Ottoman and other cultures as well. The legacy of Eastern Roman art and architecture also continued beyond the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire, for example in the icons of Crete and Russia, as well as in the paintings of the Italian renaissance in places such as Venice.

Watch videos and read an essay about Eastern Roman afterlives

Hagia Sophia as a mosque: After the Ottomans conquered Constantinople, the sultan repurposed this church as a place for Muslim prayer.

Read Now >

Mimar Sinan, Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul: This mosque was the crowning achievement of architect Sinan’s career and a trophy of Ottoman imperial grandeur.

Read Now >

Greek painters in renaissance Venice: Icons continued to be produced in places like Crete even after the fall of Constantinople, influencing the art of Venice and the Italian renaissance

Read Now >/3 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the Iconoclastic Controversy and the Fourth Crusade impact the production of art and architecture in the Eastern Roman Empire?

How did Eastern Roman (Byzantine) art and architecture influence other cultures beyond its political and historical boundaries?

How did mosaics and frescoes interact with their architectural and ritual settings in the Eastern Roman Empire, Kyivan Rus', and Norman Sicily?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the Iconoclastic Controversy and the Fourth Crusade impact the production of art and architecture in the Eastern Roman Empire?

How did Eastern Roman (Byzantine) art and architecture influence other cultures beyond its political and historical boundaries?

How did mosaics and frescoes interact with their architectural and ritual settings in the Eastern Roman Empire, Kyivan Rus', and Norman Sicily?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

apse

belfry

crusade

Deësis

flying buttress

frescoes

icon

Iconoclastic Controversy

iconoclasts

iconophiles

mosaics

mosque

muqarnas

narthex

orans

parekklesion

Romanesque

spolia

Learn more

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Dr. Evan Freeman, About the chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire

Dr. Evan Freeman, The lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine Art

Dr. Evan Freeman, Byzantine Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Art Institute of Chicago, Ancient and Byzantine Mosaic Materials

Dr. Alicia Walker, Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Middle Byzantine period

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, Middle Byzantine secular architecture and urban planning

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, Regional variations in Middle Byzantine architecture

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout, Late Byzantine secular architecture and urban planning