Periods of Byzantine history

Early Byzantine (including Iconoclasm) c. 330 – 843

Middle Byzantine c. 843 – 1204

The Fourth Crusade & Latin Empire 1204 – 1261

Late Byzantine 1261 – 1453

Post-Byzantine after 1453

The route and results of the Fourth Crusade (Kandi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Fragmentation

Crusader attacking Constantinople, pavement mosaic, c. 1213, San Giovanni Evangelista, Ravenna (photo: Evan Freeman CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In 1204, the Fourth Crusade captured the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. The Latins (as the Byzantines often referred to western Europeans during this period) looted and occupied the city until the Byzantines recaptured Constantinople in 1261.

With the fragmentation of the Byzantine state following the Fourth Crusade came a concomitant fragmentation of Byzantine architecture, which became dominated by regional developments. The period of the Latin Empire (1204 – 1261) witnessed little cultural investment in Constantinople, while new Byzantine successor states emerged: the Empire of Nicaea in northwest Anatolia; the Empire of Trebizond in northeast Anatolia; and the Despotate of Epirus in northwest Greece and Albania, whose capital was Arta.

In church architecture, the design of the naos followed planning types established in the Middle Byzantine period, while architectural forms increased in complexity, both visually and in plan, with the addition of porticoes, ambulatories, galleries, annexed chapels, and belfries. A general loosening of architectural rigor is evident in the lack of relationship between interior spaces and exterior articulation, in contrast with earlier periods.

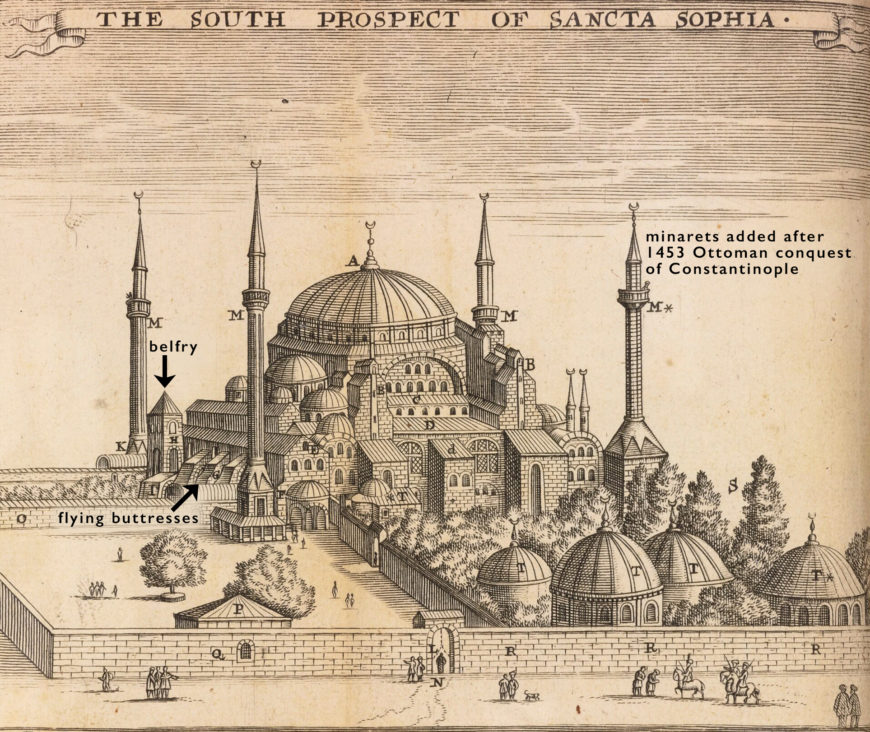

Hagia Sophia showing the belfry rising above the buttresses, Constantinople, c. 1680, print by F. H. van Hove

Constantinople

Hagia Sophia

Evidence of architecture in Constantinople in this period may be limited to the addition of flying buttresses and a belfry to the west façade of Hagia Sophia, c. 1230s. Both are new elements in Late Byzantine architecture; belfries and the use of bells became common thereafter (gothic-style buttressing less so).

Byzantine successor states following the sack and occupation of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, 1204-1261 (underlying map © Google)

Empire of Nicaea

H. Tryphonos

The lacuna created by the Latin Occupation is difficult to fill, however, although the developments in western Asia Minor during the so-called Empire of Nicaea may help to bridge the gap. While the city of Nicaea is best known from texts, the church identified as H. Tryphonos, built under the Laskarids, gives some impression of the construction of the period. Now in ruins, it had an atrophied Greek-cross naos, enveloped by ambulatories, perhaps following the model of the nearby Koimesis church, which was destroyed in 1922 (read more about the atrophied Greek-cross church type).

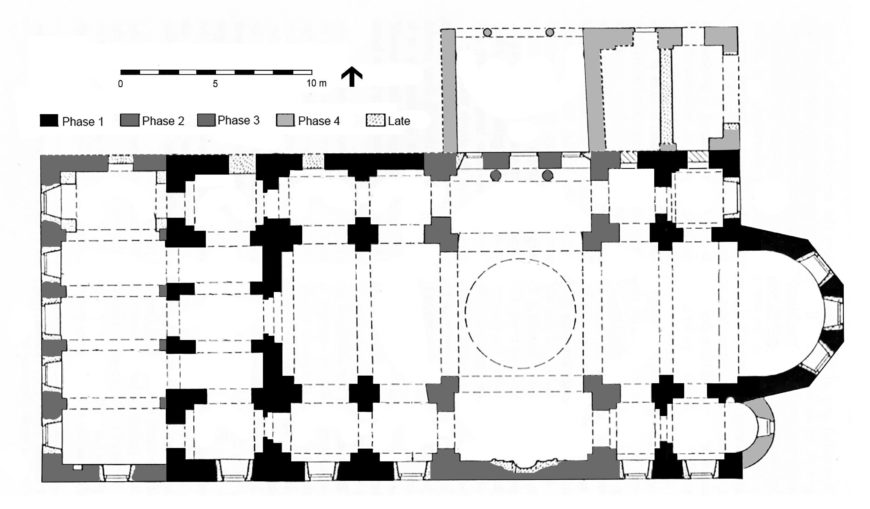

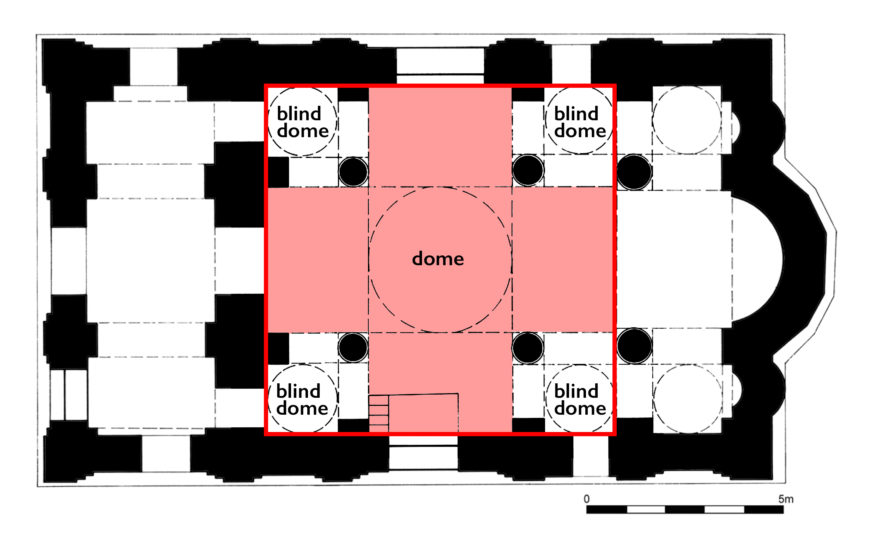

Reconstructed plan of Church E, Sardis, with cross-in-square elements highlighted (adapted from plan © Buchwald, Churches EA and E at Sardis, 2015)

Church E at Sardis

Church E at Sardis, a cross-in-square church (read more about the cross-in-square church type) known from its excavated remains, is also from this period. Topped by five domes, with those at the corners blind, the exterior featured a variety of brick patterning.

Panagia Krina, late 12th century, Chios, Greece (photo: Stylkontoz64, CC-BY-SA-4.0)

Churches at Latmos and on Chios

Churches surviving at Latmos and on the Aegean island of Chios also may belong to this period.

Frescoed interior of Panagia Krina (photo: © Francesca Guandalini and Google)

Unfortunately for most examples the chronology is not secure: Panagia Krina on Chios (modeled on the Nea Mone) for which a date c. 1225 was generally accepted, now may be placed securely before the end of the twelfth century, throwing the dating of other monuments into question.

Hagia Sophia, c. 1238–63, Trebizond (Trabzon) (photo: Julien Lagarde, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Hagia Sophia, c. 1238–63, Trebizond (Trabzon) (photo: İhsan Deniz Kılıçoğlu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Empire of Trebizond

H. Sophia, Trebizond

With the establishment of the Empire of Trebizond in northeast Anatolia, the Grand Komnenoi (the title of the emperors of Trebizond) constructed H. Sophia in the city of Trebizond, c. 1238-63, to be the mortuary church of the imperial family. Built on a cross-in-square plan, its stone construction and detailing betray its mixed origins, exhibiting both Caucasian and Seljuq features. The origin of its distinctive lateral porches remains unclear (view plan of H. Sophia, Trebizond).

Exterior and interior views of the Panagia Chrysokephalos (Fatih Mosque), 13th century with 1341 additions, Trebizond (Trabzon) (photo: © The Byzantine Legacy)

Panagia Chrysokephalos

The Panagia Chrysokephalos functioned as the cathedral and coronation church; a galleried basilica of the early 13th century, a dome and transept were added c. 1341.

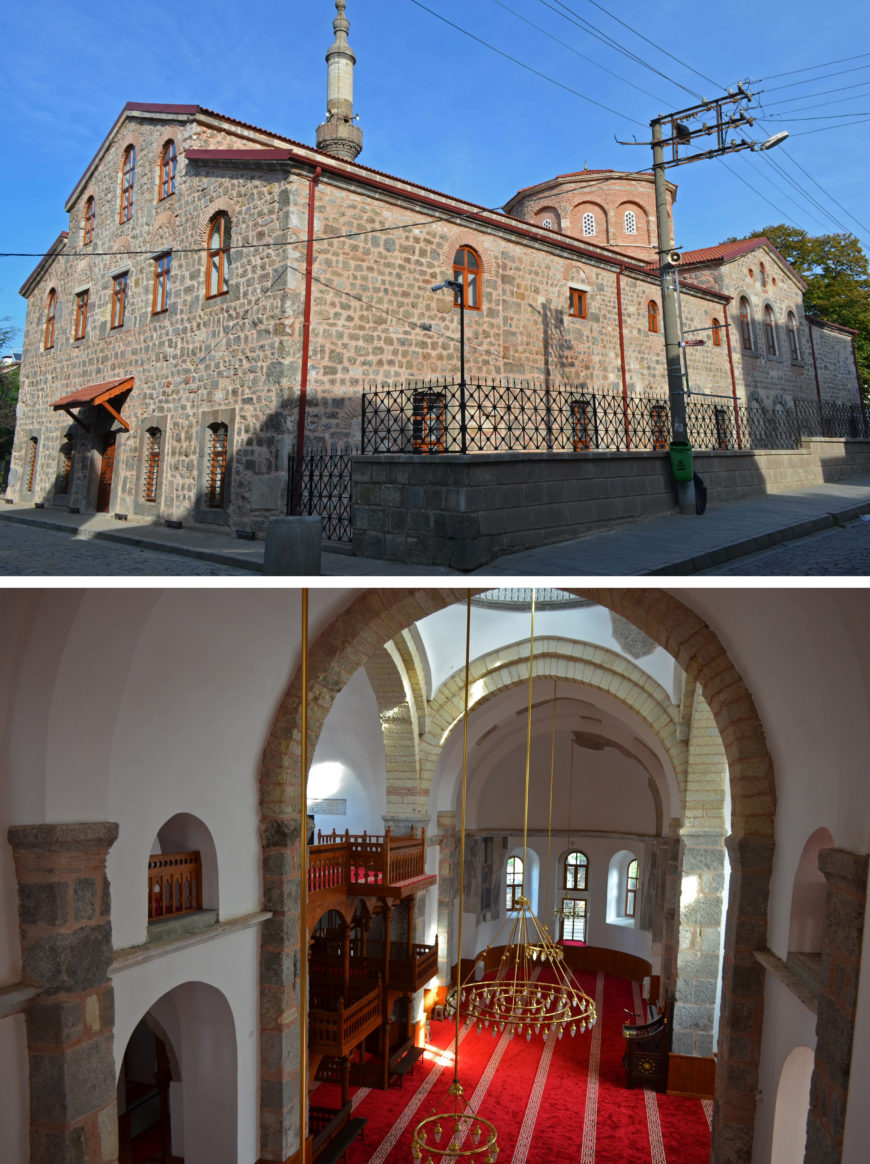

Exterior and interior views of St. Eugenios (today Yeni Cuma Mosque), 11th century, remodeled 13th and 14th centuries, Trebizond (Trabzon) (top photo: NeoRetro, CC BY-SA 3.0; bottom photo: © The Byzantine Legacy)

St. Eugenios

The major pilgrimage church of St. Eugenios, originally of the 11th century, underwent remodelings in the 13th century but only achieved its present form in the 14th. Significant construction continued at Trebizond into the fifteenth century.

Panagia Vlacherna, transformed c. 1225, Arta (photo: © The Byzantine Legacy)

Church of the Paregoretissa, 1282-89, enlarged 1294-96, Arta (photo: Jpmourez, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Arta and the Despotate of Epiros

In northwest Greece, Arta emerged as the capital of the Despotate of Epiros in this period, with numerous Byzantine churches erected or transformed under the ruling families, such as the Panagia Vlacherna (transformed c. 1225), Kato Panagia (mid 13th c.), H. Theodora (enlarged 13th c.), and Pantanassa Philippiadas (enlarged c. 1294), now in ruins.

Church of the Paregoretissa

The most important of these is the Paregoretissa in Arta (1282-89; enlarged 1294-96), apparently begun as a cross-in-square church but transformed during construction into an octagon-domed naos enveloped by a pi-shaped ambulatory surmounted by a gallery with four additional domes (read more about the octagon-domed church type).

Church of the Paregoretissa, 1282-89, enlarged 1294-96, Arta (photo: Albert Gößwein, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Here and elsewhere in Epiros, the decorative brickwork of the exterior is distinctive. At the Vlacherna, as at Kypseli and Mesopotam (Albania), complex, asymmetrical designs developed in multiple building phases. At Kypseli, Kato Panagia and elsewhere, the naoi feature high transverse barrel vaults (barrel vaults set at right angles to the main longitudinal direction of the naos) rather than domes.

St. Demetrius, 13th century, Kypseli (left) and St. Nicholas, Mesopotam (Albania) (right) (left photo: © Robert Ousterhout; right photo: Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Pointed arches in the remains of the sanctuary of the church of St. Sophia, mid 13th century, Andravida, Greece (© Robert Ousterhout)

Southern Greece

In southern Greece, part of the Byzantine territory conquered by the Latins in the early thirteenth century, a number of large basilicas were constructed in a gothic style, to serve the needs of the new, Roman Catholic population, including a variety of mendicant orders, as at Andravida, Stymphalia, Isova, and Glarenza.

The numerous small, domed churches of the Peloponnese, constructed in a Byzantine style but exhibiting gothic detailing, however, were viewed within an Orthodox Byzantine context and thus belonging to an earlier period, but this interpretation is now in question.

Church of the Koimesis, late 13th century, Merbaka, Greece (photo: © Robert Ousterhout) (view annotated photo)

Church of the Koimesis at Merbaka

The church of the Koimesis at Merbaka, a carefully constructed cross-in-square church, was lavishly decorated on the exterior with a combination of brick patterning, spolia, carved stone, and glazed proto-maiolica bowls. The last, in combination with some gothic details, place Merbaka into the latter part of the thirteenth century and within the context of Latin patronage.

The Panagia Katholike at Gastouni and the Blacherna at Elis

The churches of the Panagia Katholike at Gastouni, the Blacherna at Elis, and churches elsewhere fit into a growing picture of the architecture of southern Greece during this period as the product of a mixed workforce serving a heterogeneous clientele. These small buildings may have been private rather than institutional foundations, with their outward appearance indicative of social status rather than country of origin.

Next: read about Late Byzantine church architecture

Additional Resources

Smarthistory’s free Guide to Byzantine Art e-book

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)