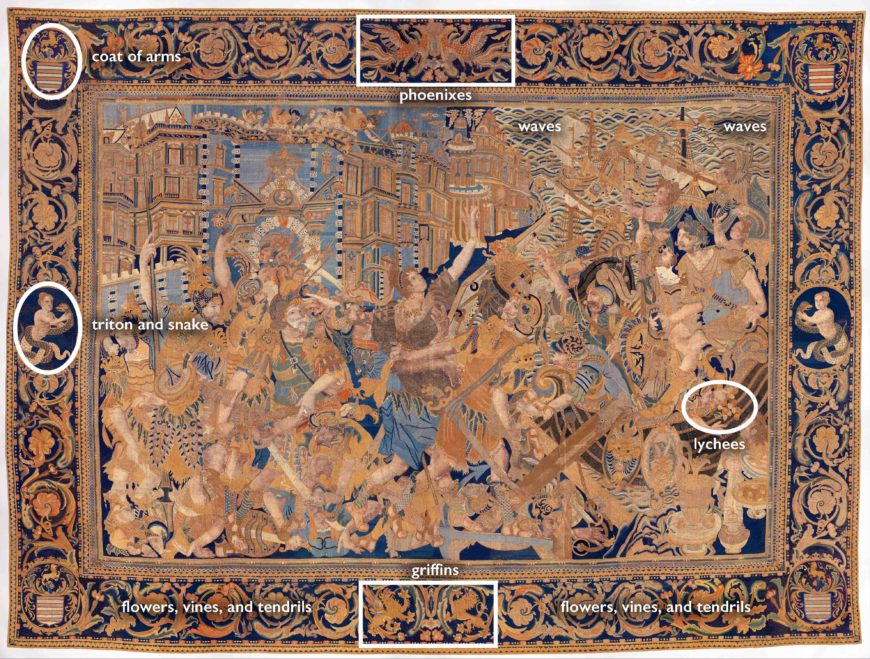

The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The story of Troy

Twisting, overlapping warriors fill the foreground of a massive 12 x 16 foot tapestry. It can be difficult to tell where one person begins and another ends, making the scene seem chaotic. Behind the figures, a cityscape rises on the left, while on the right waves jostle ships. If we look closely at the center, we can see a woman dressed in sumptuous clothes, her right arm raised in protest as two men abduct her.

Detail of Menelaus, The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

To the left, a white-bearded warrior glances towards the struggling woman as she is carried toward another man who stands in one of the boats in the harbor at the right.

This scene is the abduction of Helen—the Achaean (or Greek) woman whose beauty was famous. Paris, the Trojan prince, abducts her from Sparta, causing the Trojan War (the story recounted in Homer’s Iliad from the 8th century B.C.E.) The moment of the abduction became a popular subject in 15th-century Europe. Objects displaying this disturbing scene were even believed to be appropriate for the celebration of a wedding, because the bride’s beauty could be compared to Helen’s. Some versions of the story recount Helen and Paris falling in love. The popularity of the subject reveals how ideas about sex, power, and violence were intertwined at this time.

The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Framing the main scene are borders filled with vines, flowers, grotesques, griffins, lions, serpents, tritons (mermen, often with tridents), and even coats of arms. Phoenixes and lychees (a small round fruit with rough skin) can also be found—both common Chinese decorative elements.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 381 x 523.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This luxurious tapestry—made of cotton and embroidered with silk, gilt-paper-wrapped thread, and oil paint—was one in a series about the story of Troy. Three are now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, while the other four are in different collections, showing scenes such as sacrifice of Polyxena and the prophecy of Calcas. The Abduction of Helen not only reflects the popularity of the Trojan story for 16th– and 17th-century European audiences, but also speaks to the importance of a global textile trade and the international scope of European-influenced art schools. This tapestry was made in China to be sold in Portugal, and it is an example of a transcultural object, or one entangled with multiple cultures.

Let’s take a closer look at this fascinating tapestry.

The Battle with the Sagittary and the Conference at Achilles’ Tent (from Scenes from the Story of the Trojan War), c. 1470–90, wool warp, wool wefts with a few silk wefts, 436.9 × 396.2 cm, probably produced through Jean or Pasquier Grenier, Made in Tournai, South Netherlands (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tapestries

Tapestries depicting the story of Troy were popular among elites in early modern Europe. A late 15th-century tapestry made in the southern Netherlands is among the earliest that still exists, and it shows a chaotic battle scene and a meeting with Achilles (the most famous Greek warrior) on the lower right. The tale of the war between Greek and Trojan heroes interested humanist intellectuals, who valued Greco-Roman literature. In 1472, Charles the Bold (the 4th Duke of Burgundy) reportedly commissioned the first set of tapestries about Troy (that we know of). He had an impressive tapestry collection that provides a glimpse of the different subjects that a wealthy noble might own. His collection included tapestries with Christian subject matter (like the Passion of Christ), ancient and medieval hero stories (like the Trojan War, Jason and the Golden Fleece, or Charlemagne’s military exploits), allegories and romances (like the popular bestseller the Romance of the Rose), and pastoral scenes filled with shepherds and hunters. Tapestries could hang on walls or attach to columns and pillars to visually enrich a space (and even to help keep it warm) and display the owner’s status. Unlike a mural, a tapestry is portable, which suited the needs of itinerant (on the move) elites and rulers who often traveled to different palaces or for war—they could bring their expensive decorations with them.

Detail of Paris, The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Abduction of Helen tapestry draws on classical and post-classical textual sources: the ancient epic by Homer the Iliad; medieval and renaissance stories that elaborated on the original story; and printed images about the story. With the advent of printmaking in Europe in the mid-15th century, prints became important sources for the imagery we observe on tapestries. Unfortunately, the exact print or prints on which The Abduction of Helen was based have not been identified.

Detail of Helen, ships, and waves, The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A Chinese tapestry for the Portuguese market

Turning to the upper right of the tapestry, we notice that the artists embroidered Chinese-styled waves. Striking contrasts of color—blues, greens yellows, and white—undulate across the surface without ever blending together to imply the sea’s movement.

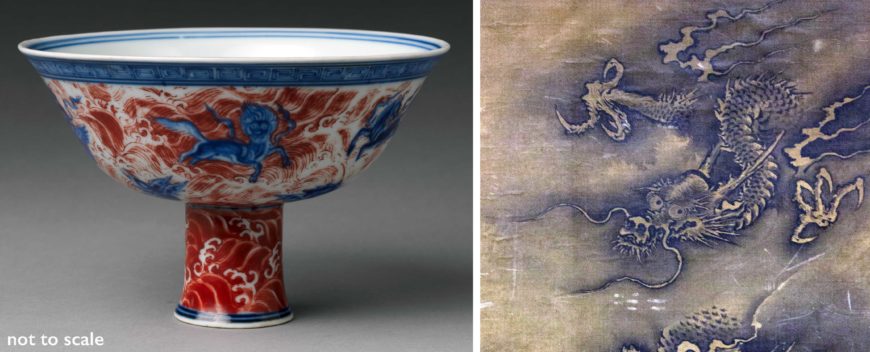

Examples of Chinese-style waves (left) and dragon scales on a Ming dynasty painted scroll (right). Left: Altar bowl with winged animals among waves, mid-15th century (Ming dynasty), porcelain painted with cobalt blue under and red enamel over transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware), China, 15.6 cm in diameter and 10.8 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Dragon Amid Clouds and Waves (detail) 15th–16th century (Ming dynasty), hanging scroll; ink on silk, China, 109 x 67 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

When we look closely, we see many borrowings from Chinese art.

There are the lychees and phoenixes in the border (see the annotated image above or click here). The faces and decorative patterning on the warriors’ armor, and the scales of the serpents and tritons in the borders also borrow from Chinese art—we see similar forms on 17th-century Ming dynasty painted scrolls, ceramics, and textiles.

One warrior’s helmet appears made of dragon’s scales such as we see in a Ming dynasty hanging scroll. The faces on his shoulder armor look similar to a dragon’s face too.

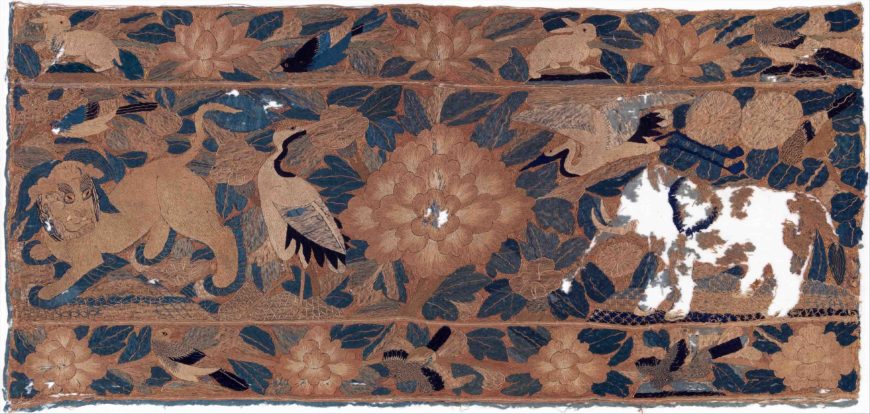

Chinese tapestry for the Iberian market, 16th century, silk and metal thread, 208.3 x 190.5cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The increasingly globalized world created new markets that stimulated the manufacture of tapestries like this one. Beginning in the 16th century, Chinese artists made many tapestries for the Iberian market (Spain and Portugal), and they often demonstrate the weaving together of different visual and symbolic traditions, such as in the Abduction of Helen tapestry. Others, including a 16th-century tapestry, draw more clearly on popular motifs in Chinese art, such as lions, cranes, elephants, rabbits, and lotus blossoms.

The coat of arms in the corners of the Abduction of Helen tapestry also suggest the interesting origins of this tapestry. They are possible renditions of the coats of arms of the Mascarenhas family of Portugal. Francisco Mascarenhas was governor of Macau between 1623 and 1626. Macau, where this tapestry was likely traded from, was a major trade center and port city in the 16th century on the south coast of China. The city was also an important city for the Portuguese empire.

Macau and the Portuguese

The Portuguese first arrived in Asia with Vasco da Gama’s explorations in 1497–98, when he arrived in India. Portuguese interest in Asia grew, leading to the conquest of Malacca (in Malaysia) in 1511. The Portuguese king also hoped that establishing good relations with Chinese rulers might result in a mutually beneficial trade arrangement. Several different Portuguese embassies traveled to China, but eventually the Ming emperor banned their entry. Still, illicit trade ensued, and the Portuguese were eventually permitted to establish a trade center in certain areas of southern China, like Macau (in 1557), provided the Portuguese paid taxes.

Chinese dish for European market, later 17th century, Hard-paste porcelain with cobalt blue under transparent glaze, 28.6 cm diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The settlement in Macau proved extremely lucrative for both the Portuguese and Chinese, and it initiated an appetite for Chinese import items into Europe and beyond. Chinese silks (both raw and manufactured), blue-and-white porcelain, and tapestries were among the many items that circulated on a global scale. Chinese artists also encountered European prints and other portable objects that provided models for European subject matter and styles. The story of Troy series was possibly made in Guangzhou (an important center for tapestry production in China) before traveling to Macau.

Detail of Paris and another Trojan (on the left) , The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

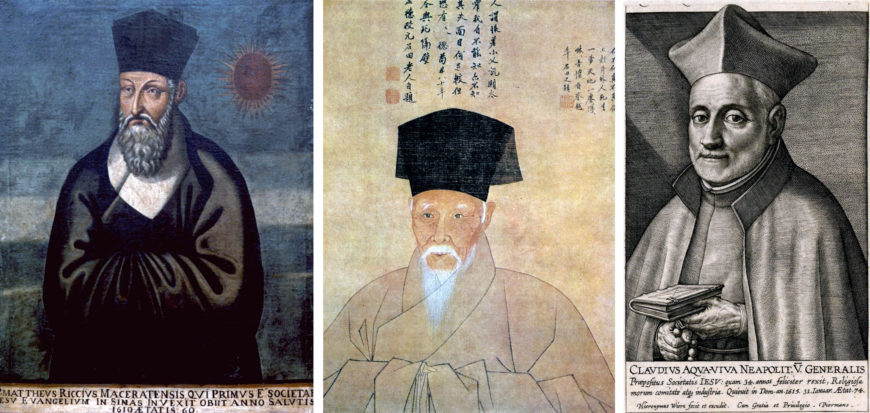

In Macau, painters trained in European Jesuit-established art schools were likely responsible for painting the faces and limbs of the figures in the Abduction of Helen tapestry (painted directly onto the cotton). The Jesuits are a Christian religious order founded in 1540. In the 16th century, members headed to China to convert people there to Christianity, beginning with the voyages of Francis Xavier (a founding member of the Jesuit order). In places like Macau and Japan, the Jesuits established art schools to train local artists in European visual vocabulary and subject matter. In 1583, Giovanni Niccolò established a famous school in Japan, but it was relocated to Macau after Japan decreed Christianity illegal in 1614. At these schools, artists like You Wenhui (known in Portuguese as Manuel Pereira) and Ni Yicheng (in Portuguese, Jacopo Niva) learned European renaissance techniques, such as using light and shadow to develop convincing three-dimensional bodies.

Left: You Wenhui 游文輝 (alias Manuel Pereira), Fr. Matteo Ricci of Macerata, c. 1610, oil on canvas, 120 × 95 cm. (© Society of Jesus, Il Gesù, Rome); center: Portrait of Shen Zhou 沈周, 1507, ink & color on silk (Palace Museum, Beijing); right: Hieronymus Wierix, Portrait of Claudio Acquaviva, bust, facing front, wearing the Jesuit habit and hat, holding a closed book and a rosary, 1615-1619, from the series Effigies Praepositorum Generalium Societatis Iesu, engraving (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

In You Wenhui’s portrait of the Jesuit Mateo Ricci (who had spent 28 years as a missionary in China and died in 1610), today in the Il Gesù church in Rome, we see the elderly, bearded Jesuit with a black hat and black flowing robes, his hands hidden in his sleeves. The portrait looks like a combination of Chinese scholar portraits of the Ming dynasty (such as Shen Zhou wearing a cap and with his hands inside his robes) and European Counter-Reformation portraits (such as engraving of the Jesuit Claudio Acquaviva, with its simplicity and the informative inscription at the bottom). Paintings like Ricci’s portrait also reveal the ongoing artistic negotiations at work in places like Macau, and China more broadly. Even the very materials of objects like the Ricci portrait and the story of Troy tapestries reveal the cultural entanglements of this era. Some of the tapestry’s pigments include a white favored in Japanese art, and a blue-green not typically used in Asia.

The Abduction of Helen, from a set of the story of Troy, first half of the 17th century, cotton, embroidered with silk and gilt-paper-wrapped thread, pigment, from China, for the Portuguese market 3.6 x 4.8 m (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The complexity of cultural entanglements

On a single tapestry showing scenes from a well-known ancient Greek story, we are invited to think more deeply about the transcultural processes occurring in the 16th and 17th centuries and how we understand them today. Like the overlapping, twisting bodies of the warriors that are challenging to make out on the tapestry, so too is it difficult to categorize this tapestry by place, style, or artists. Is it renaissance or baroque art? Chinese art? On a site like Smarthistory, where do we locate this tapestry? Transcultural objects will continue to push art historians to rethink how we categorize art, especially since most of those categories were developed without complex, culturally entangled works like the Abduction of Helen in mind.