Even in death, great Roman families were concerned with reinforcing and projecting their status.

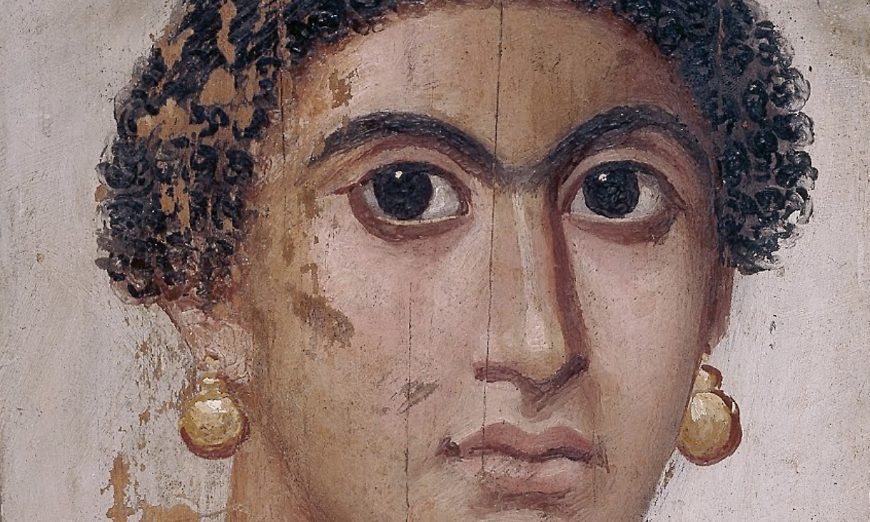

Plaster cast of the Tomb of Scipio Barbata in-situ, early 3rd century B.C.E. (original, Vatican Museums) (photo: Caterina A., by permission)

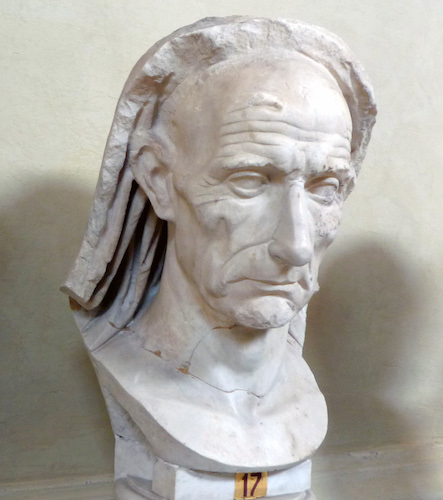

Veristic male portrait (similar to Head of a Roman Patrician), early 1st Century B.C.E., marble, life size (Vatican Museums, Rome) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Image and status

The latter days of the Roman Republican period witnessed socio-economic upheaval, and a long-established social order found itself threatened by newcomers who were wealthy but lacking in illustrious social pedigrees. Roman aristocrats in the patrician class (those threatened by this socio-economic upheaval) linked their ancestors to the founders of the Roman state, and projected an image of themselves as aged and wise as a measure of their experience and acumen (see Head of a Roman Patrician).

Since image and status are frequently linked, these aristocrats had long relied on display as part of cultivating their status. Whether this was the display of the images of illustrious family members in the atrium of their houses (so-called imagines), or the constructions of tombs or other patronage projects, material culture mattered in maintaining status. The Late Republican period (the late 2nd and 1st centuries B.C.E.) witnessed several significant examples of this attempt to maintain status in a changing world.

The family of the Cornelii Scipiones

The Cornelii Scipiones were among the most famous Romans of all. Their ancestors had won many victories—including those of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus (who died c. 280 B.C.E.) and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (who died c. 183 B.C.E.), the victor in the Second Punic War. The family tomb of the Cornelii Scipiones, located along the Via Appia leading south from the city of Rome, was first rediscovered in 1614. Its remains constitute one of the most important examples of Late Republican funerary culture at Rome and demonstrate how an illustrious family worked to maintain its image in a changing world.

The Tomb

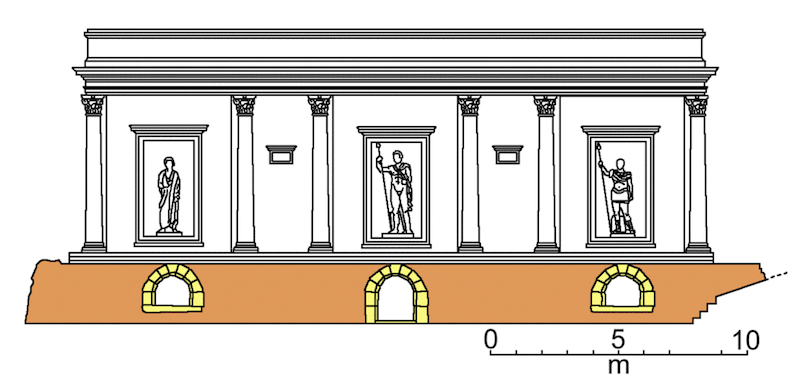

Possible reconstruction of the Scipio’s tomb on the via Appia, Rome, third century B.C.E. – first century C.E.

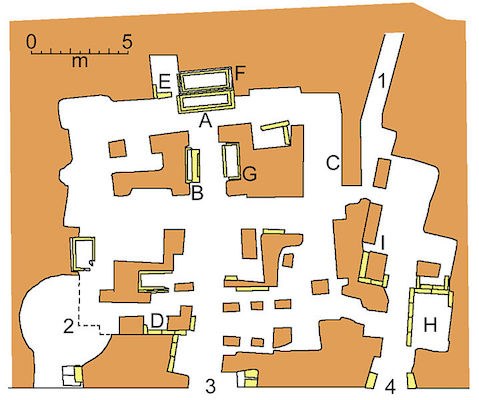

The Tomb of the Scipios is a subterranean, rock-cut tomb (hypogeum) composed of irregular chambers and connecting corridors that provide niches for burials (see plan and interior view below).

Plan of the Tomb of the Scipios in Rome. 1) the old entrance; 2) a “calcinara,” mediaeval lime kiln; 3) the main entrance; 4) entrance to the new room. The letters from A to I are the sarcophagi or loculi with inscriptions. The tomb is now empty except for facsimiles; the remains were discarded or reinterred, while the sarcophagi fragments ultimately went to the Vatican (based on a plan by Filippo Coarelli, Coarelli, Il Sepolcro degli Scipioni a Roma. Itinerari d’arte e di cultura (Rome: Fratelli Palombi, 1988).

The tomb was begun in the early years of the third century B.C.E. and continued in use until the first century C.E. The family’s patriarch, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, who served as consul in 298 B.C.E. is the most prominent occupant of the tomb. Barbatus was buried in a monumental stone sarcophagus with a Latin inscription (see below). Other family members occupy other parts of the tomb, in many cases with inscriptions identifying the individuals and charting their public careers.

As the tomb faced an important roadway, it came to have an elaborate façade in its later phases. This façade likely dates to c. 150 B.C.E. or later when the family renovated and expanded the tomb. In addition to the architectural elements of the façade, a fresco depicting a processional scene—perhaps of famous members of the Cornelii Scipiones—adorned the tomb.

The Sarcophagus of Barbatus

Scipio Barbatus was deposited in an elaborately carved sarcophagus (today the original is in the Vatican Museums—image below, and a plaster cast is in situ—image here). The façade of the sarcophagus is decorated with a Doric frieze and volute scrolls adorn the lid (watch a video about the classical orders). It included an elaborate Latin epitaph that was modified in antiquity, with some earlier text being erased. The Scipios were always keen to maintain family ties and support their ancestry at any cost. The extant text of the Barbatus epitaph records civic career achievements (Barbatus served as consul, censor, and aedile) and military achievements. In the latter category Barbatus was famous in Rome’s third century B.C.E. wars with the Samnites; the epitaph tells the reader that he captured Taurasia and Cisauna in Samnium, in addition to subduing the region of Lucania (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum VI, 1285).

Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus, early 3rd century B.C.E. (Vatican Museums) (photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.0)

Conclusion

The Tomb of the Scipios is an important monument that demonstrates Roman methods of using images to reinforce and project status. The competition to maintain social rank and position was fierce, and latter day members of the Cornelian family (gens Cornelia) were indeed trading on the names and reputations of their more famous ancestors as they themselves struggled for traction in the tumultuous period at the end of the Roman Republic.

Below is a Google photosphere, showing a Late Republican columbarium (for storage of funerary urns), adjacent to the Tomb of the Scipios that was used for cremation burials and, together with the elite Tomb of the Scipios, was located within a large necropolis located along the Via Appia exiting the city of Rome from the south: