For the first time, a Roman emperor celebrated victory over fellow Romans, and appropriated the art of earlier rulers.

Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker. Video produced by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in Rome, standing in front of the Arch of Constantine.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:08] This is such an interesting and problematic monument. It’s one that scholars are still debating today. And not too far away is the Arch of Titus, and not too far away from that is the Arch of Septimius Severus, and there was also an arch to Marcus Aurelius that doesn’t survive.

Dr. Zucker: [0:23] Arches were built to celebrate especially important military victories. This particular arch is the first arch that celebrates a victory, not over a foreign power, but over a Roman rival.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] Let’s start by looking at the arch.

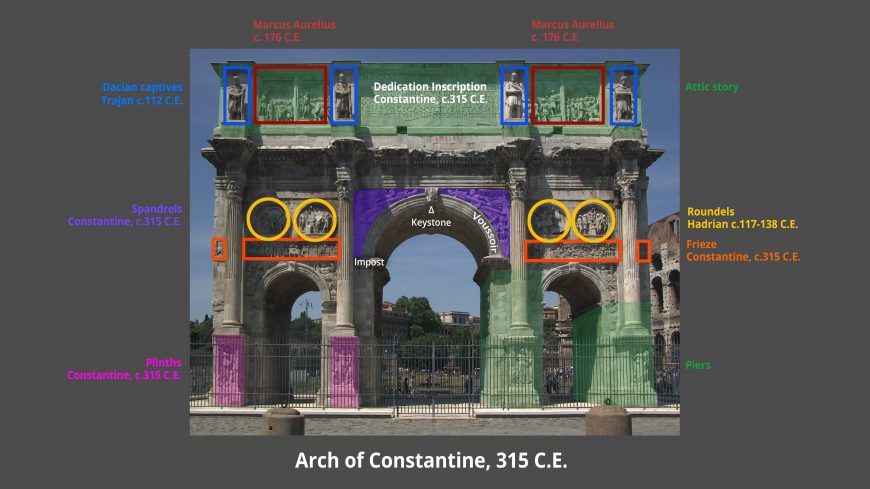

Dr. Zucker: [0:37] The surface is covered with sculpture.

Dr. Harris: [0:39] To make it even more complicated, the sculpture dates from different time periods in Roman history.

Dr. Zucker: [0:45] So, many of these sculptures weren’t even made by Constantine. He was reusing them from earlier monuments that had been built by earlier emperors.

Dr. Harris: [0:54] The emperors Marcus Aurelius, Hadrian, and Trajan, those are three of the five what are known as “good emperors,” who were seen to be especially benevolent emperors in Roman history. Here, Constantine seems to be associating himself with three of those five good emperors by bringing in sculptures from their monuments here into his own.

Dr. Zucker: [1:16] Let’s start with the sculptures at the top. It’s a little bit hard to get a sense of just how large those figures are, but I’m estimating that they stand about 10 feet tall.

Dr. Harris: [1:25] These freestanding figures are borrowed from monuments belonging to the emperor Trajan, and these represent Dacian prisoners.

Dr. Zucker: [1:34] Dacia was more or less what we call Romania, and this was an area that had been previously conquered by the emperor Trajan.

Dr. Harris: [1:40] We can tell that they’re Dacians. We can tell that they’re foreigners by the fact that they wear beards and by their clothing. They would have been easily identifiable as non-Romans.

Dr. Zucker: [1:50] As barbarians, which simply means “foreigner.”

Dr. Harris: [1:53] What we see here are figures that have been conquered by the Roman Empire, and this is a theme that reappears throughout the arch in different forms, subjecting foreign peoples to the power of the Roman Empire. The panels in between the Dacians are from monuments belonging to the emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Dr. Zucker: [2:14] This is not freestanding sculpture, this is high-relief sculpture, and if we start [on] the left, we see the presentation of a client king.

Dr. Harris: [2:22] Presenting to the Roman people a foreign king who has been captured.

Dr. Zucker: [2:26] Next to that, Marcus Aurelius receives barbarian prisoners. Then, to the right we have an address, presumably Marcus Aurelius speaking to his soldiers, speaking to the people. Then finally on the right, Marcus Aurelius making a sacrifice before a battle.

[2:40] Then, if we walk around the arch, on the other side, we have four additional panels from Marcus Aurelius. These are the arrival of Marcus Aurelius into Rome, Marcus Aurelius leaving Rome, the distribution of largesse– that is, Marcus Aurelius distributing money to the Roman people — and the submission of the barbarian prisoners.

[2:59] Look at the beauty of those reliefs. They are very much in the classical style. The bodies flow easily, they’re in complex poses, there is a high degree of naturalism.

Dr. Harris: [3:09] Many of the figures stand in contrapposto; their drapery reveals the form of their body underneath in folds that are three-dimensional. This is an important thing to note for some of the other sculptures we’re going to look at later.

[3:22] Below that, we see freestanding columns in front of pilasters, all with Corinthian capitals, and between those columns, we see roundels. That is, scenes set in round frames.

Dr. Zucker: [3:36] This is some of my favorite decorative sculpture on the arch.

Dr. Harris: [3:39] These all come from monuments relating to the emperor Hadrian.

Dr. Zucker: [3:45] Remember, Hadrian was one of the “good emperors.”

[3:47] On the south side from left to right, we have departure for the hunt, a sacrifice to the god Silvanus, a bear hunt, and a sacrifice to the goddess Diana.

[3:58] On the north side, starting on the left, is a boar hunt, a sacrifice to the god Apollo, and then, against a field of purple porphyry, which is an extremely expensive semiprecious stone, is a roundel depicting the aftermath of a lion hunt, and the sacrifice of Hercules.

Dr. Harris: [4:15] It’s important to remember that the emperor was traditionally the head of the Roman state religion, so making sacrifices to the gods; and then hunting, something that was reserved for the elite, a sign of strength for the emperor.

Dr. Zucker: [4:31] Just like the panels above, the roundels are sculpted in high relief, and the roundel that shows the sacrifice to Apollo I think is especially beautiful. It reminds us that this is the classical tradition that the Romans had borrowed from the ancient Greeks.

Dr. Harris: [4:44] Look at the figure of Apollo standing semi-nude in lovely contrapposto, and the horse moving out into our space, so this incredible naturalism, not only in the body, but even in the treatment of space.

[5:00] As we move below the roundels, we finally get to some sculpture that dates from the time of Constantine. It’s a band that wraps around the entire arch, and tells what really was the critical story for Constantine.

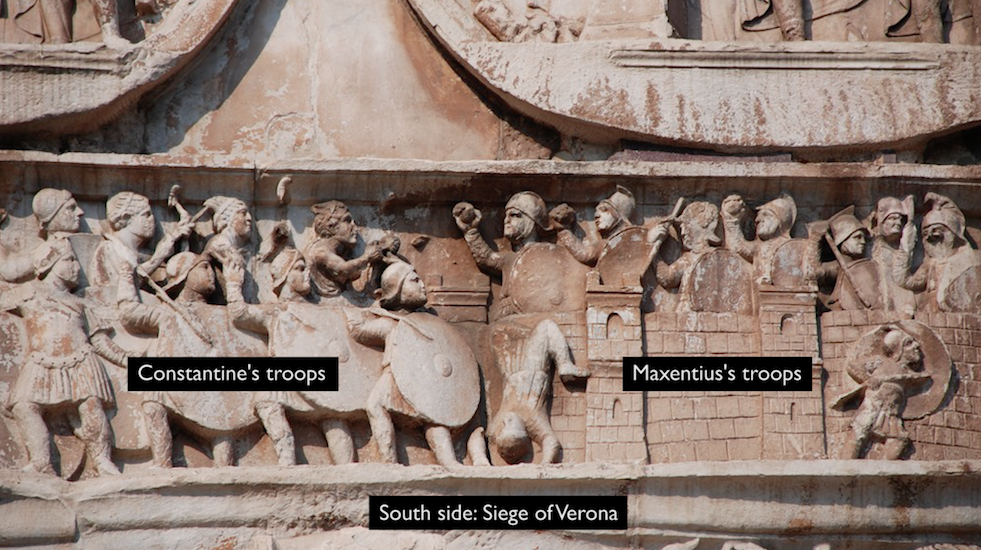

Dr. Zucker: [5:14] We’re not entirely sure, but many scholars believe that we should start on the west side of the arch, which shows Constantine’s army making its way to Verona to attack the army of another Roman emperor, Maxentius.

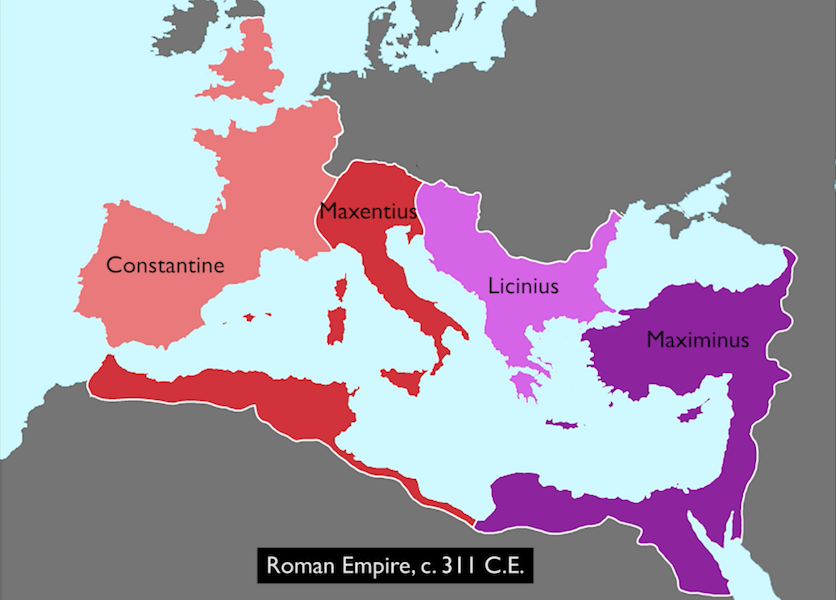

Dr. Harris: [5:28] This is a complicated moment in Roman history. For some time, the Empire had been ruled not by a single emperor, but by four emperors — two senior emperors and two junior emperors — a system of government that was called a tetrarchy. The idea was that with four rulers in such a vast empire, you would bring some political stability.

Dr. Zucker: [5:51] There were two rulers who were responsible for the east and two rulers that were responsible for the west. Constantine was one of the emperors that was responsible for the western empire.

Dr. Harris: [6:02] He went to battle against Maxentius, who was his co-ruler in the west.

Dr. Zucker: [6:07] The next panel shows Constantine laying siege to the city of Verona and to Maxentius’ troops. Then across the large bay, the most famous scene, this is the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. This is when the two armies confront each other just outside of Rome.

Dr. Harris: [6:23] Constantine defeats Maxentius, and Maxentius is killed at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. This is the decisive battle that puts Constantine in charge of the western part of the Roman Empire.

Dr. Harris: [6:34] The panel on the east side of the arch shows Constantine entering the city of Rome. Then, on the north side, we have two final panels, the oratorio at the rostrum and the distribution of money to the Senate and the Roman people. Let’s look at the distribution of largesse.

[6:52] The thing that strikes me most is just how different stylistically the carving is. Whereas the panels that had been borrowed from earlier monuments are so clearly classical in their representation, here the figures are squat, the beautiful proportions of the human bodies have become stunted, and the roundness of the forms, the careful definition of drapery, is now simply incised markings. They seem almost like drawings, not sculpture.

[7:18] About a century ago, when art historians looked at this contrast between styles, they thought what they were seeing was evidence of the decline of the Roman Empire, of the decline of the artistic capabilities of the sculptors of the day, that is, somehow this more simplified form was less good.

[7:35] What some art historians now conjecture is that Constantine’s imagery is not meant to compete stylistically. That it had a different purpose, that it was valued for its clarity.

Dr. Harris: [7:45] The lack of concern for the correct proportions of the human body, the lack of interest in a space for bodies to exist in, these are characteristics that we associate with early Christian art. And in fact, Constantine is the pivotal figure there.

[8:02] He makes it possible for Christians to practice Christianity legally within the Roman Empire with the Edict of Milan, and becomes, by legend, a Christian himself at the end of his life.

Dr. Zucker: [8:13] We know that the style of early Christian art is, to some extent, meant to function symbolically rather than naturalistically. What’s most important to Constantine’s sculptors is clarity. They want to make sure that we know that Constantine is the figure in the middle. He’s twice as large as every other figure.

[8:30] Sadly, he’s lost his head at this point, but we can just make out that his arm is outstretched and he’s holding a tray of coins, which are falling into the lap of a man who seems to be gathering the coins in his toga.

Dr. Harris: [8:43] Senators at the top pass the emperor additional coins. We even see some children receiving the emperor’s generosity. This is a very symmetrical composition, with the emperor smack in the middle and all of the figures turning their attention to him. There’s that idea of clarity and legibility. Then we have these four interesting scenes, two on either side.

Dr. Zucker: [9:07] These are the bureaucrats that count and keep track of the money of the state and make possible the distribution of money that we see in the central scene.

Dr. Harris: [9:14] There’s a sense of a well-organized Roman government. If we go below, we see sculpture in the spandrels that also date from the time of Constantine. Most of these show Victory figures, some of them show Roman gods, and also the seasons.

Dr. Zucker: [9:30] Then in the bases of the columns, you see additional relief carvings. These are also Constantinian, and they show Victories and subjugated barbarians. The last two major panels are found inside the main archway.

Dr. Harris: [9:43] On one side, we see an inscription that translates [as] “bringer of peace.” Here we see on the left the emperor being crowned by a figure of Victory and on the right, a battle scene.

Dr. Zucker: [9:55] The opposite panel shows Trajan on horseback, trampling a barbarian, and the inscription above reads “liberator of the city.” These two enormous inner panels are from the era of Hadrian, but he made them not of his own exploits, but of the exploits of the previous emperor, Trajan.

Dr. Harris: [10:12] The fascinating thing throughout this monument is that the heads of these previous emperors are often re-carved to the features of the emperor Constantine. Constantine not only took these monuments from previous emperors, but had the faces of the emperors re-carved in his own image.

[10:32] What are we to make of a monument that is essentially a collage, where the emperor re-carved the faces of these good emperors, in many cases, and gave them his own features? What did the Roman people make of this? This is something that art historians and archaeologists are still debating today.

Dr. Zucker: [10:51] Art historians struggle with what the arch means because each of the sculptures within it had its own meaning. Now, together, these sculptures from different periods have even more complex layers of meaning, and all of this within the complex fabric of the city of Rome itself.

Dr. Harris: [11:06] We’re looking at it against the backdrop of the Colosseum. The spot that the arch is located on was part of the triumphal route that generals would take during ceremonial parades through the city of Rome, up the Sacred Way to the Capitoline Hill.

Dr. Zucker: [11:24] Ultimately, Constantine is bringing these fragments together to place himself in the lineage of good emperors, to present himself to the city of Rome and to history as a victorious military ruler but also as a good provider for the state.

[11:39] [music]

The Emperor Constantine, called Constantine the Great, was significant for several reasons. These include his political transformation of the Roman Empire, his support for Christianity, and his founding of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul). Constantine’s status as an agent of change also extended into the realms of art and architecture. The Triumphal Arch of Constantine in Rome is not only a superb example of the ideological and stylistic changes Constantine’s reign brought to art, but also demonstrates the emperor’s careful adherence to traditional forms of Roman Imperial art and architecture.

Location and Appearance

Reconstruction of the location of the Arch of Constantine (lower left) and the sculpture of the Colossus of the Sun (center)—both situated between the Temple of Venus and Roma (far left) and the Flavian Amphitheater (Colosseum—right), model © 2008 The Regents of the University of California; image © 2008 The Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia. Courtesy Dr. Bernard Frischer (Rome Reborn 2.0)

The Arch of Constantine is located along the Via Triumphalis in Rome, and it is situated between the Flavian Amphitheater (better known as the Colosseum) and the Temple of Venus and Roma. This location was significant, as the arch was a highly visible example of connective architecture that linked the area of the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum) to the major entertainment and public bathing complexes of central Rome.

The monumental arch stands approximately 20 meters high, 25 meters wide, and 7 meters deep. Three portals punctuate the exceptional width of the arch, each flanked by partially engaged Corinthian columns. The central opening is approximately 12 meters high, above which are identical inscribed marble panels, one on each side, that read:

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the Greatest,

pious, fortunate, the Senate and people of Rome,

by inspiration of divinity and his own great mind

with his righteous arms

on both the tyrant and his faction

in one instant in rightful

battle he avenged the republic,

dedicated this arch as a memorial to his military victory

The end of the Tetrarchy

Frieze with Constantine’s siege of Maxentius’s troops at Verona (before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge), Arch of Constantine (south side) , 312-315 C.E. and older spolia, marble and porphyry, Rome

Beginning in the late 3rd century, the Roman Empire was ruled by four co-emperors (two senior emperors and two junior emperors), in an effort to bring political stability after the turbulent 3rd century. But in 312 C.E., Constantine took control over the Western Roman Empire by defeating his co-emperor Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (and soon after became the sole ruler of the empire). The inscription on the arch refers to Maxentius as the tyrant and portrays Constantine as the rightful ruler of the Western Empire. Curiously, the inscription also attributes the victory to Constantine’s “great mind” and the inspiration of a singular divinity. The mention of divine inspiration has been interpreted by some scholars as a coded reference to Constantine’s developing interest in Christian monotheism.

Sculpture from different eras

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Arch is its eclectic and stylistically varied relief sculptures. Some aspects of the sculpture are quite standard, like the Victoria (or Nike) figures that occupy the spandrels above the central archway or the typical architectural moldings found in most imperial Roman public and religious architecture (below).

Victoria (Nike) figures (personifications of victory, spandrels, Arch of Constantine (north side), 312-315 C.E. and older spolia, marble and porphyry, Rome

Other sculpted elements, however, show a multiplicity of styles. In fact, most scholars accept that many of the sculptures of the arch were spolia taken from older monuments dating to the 2nd century C.E. Although there is some scholarly disagreement on the origins of the sculptures, their imperial style corresponds to those of the reigns of Trajan (ruled 98-117 C.E.—the figures surmounting the decorative columns), Hadrian (ruled 117-138 C.E.—the middle register roundels), and Marcus Aurelius (ruled 161-180 C.E.—the large panel reliefs on the top registers). Most of the reliefs feature the emperors participating in codified activities that demonstrate the ruler’s authority and piety by addressing troops, defeating enemies, distributing largesse, and offering sacrifices.

Diagram of the Arch of Constantine showing architectural features and spolia, 312-315 C.E., Rome (link to large image)

Some sculptural elements of the structure also date to Constantine’s reign, most notably the frieze which is located immediately above the portals. These relief sculptures are of a drastically different style and narrative content when compared with the spoliated (older, borrowed) sections (below, left); Constantine’s relief sculptures (below, right) feature squat and blocky figures that are more abstract than they are naturalistic.

Two reliefs from the Arch of Constantine: left: roundel showing Sacrifice to Apollo, era of Hadrian, c. 117-138 C.E.; right: detail, Distribution of Largesse, era of Constantine, 312-315

The Constantinian reliefs also depict historical, rather than general events related to Constantine, including his rise to power and victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge. There is also a scene of Constantine distributing largesse (funds) to the public—recalling the scenes of emperors from the earlier sculptures.

Clarity of form

Regarding style, the relief figures from Constantine’s age still seem like outliers. Yet in comparison to the idealized naturalism of the earlier sculptural elements (for example, in the roundels in the image below), the thick, bold outlines of the Constantinian figures render them remarkably legible to passersby. While the Constantinian figures lack natural aesthetics, their clarity of form ensured that they were informative and communicated Constantine’s official (and celebrated) history to viewers of his own time.

Reliefs from the south side of the Arch of Constantine. Roundels, Aftermath of a lion hunt (left) and Sacrifice to Hercules (right), era of Hadrian, c. 117-138 C.E. and the frieze below, showing the Distribution of Largesse, era of Constantine, 312-315 C.E.

Analysis and Meaning

Until relatively recently, art historians viewed the blocky sculptures and use of spolia in the arch as signs of poor craftsmanship, deficient artistry, and economic decline in the late Roman Empire (this reading is now almost wholly rejected by art historians). Even one of the most prolific and influential art historians of the modern age, Bernard Berenson, titled his short book on the arch, The Arch of Constantine: The Decline of Form. More recently, however, analysis of the arch has focused on the political and ideological goals of Constantine and the objectives of the artists, which has highlighted new possibilities for the interpretation of the arch.

If, indeed, the spoliated (older) material from the arch can be traced to the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, then it situates Constantine as one worthy of the same level of reverence as those emperors—all of whom earned deserved levels of acclaim. This was vitally important to Constantine, who had himself essentially bypassed lawful succession and usurped power from others. Moreover, Constantine encouraged major social changes in Rome, such as decriminalizing Christianity. Any religious change was a threat to the ruling and political classes of Rome. By aligning himself with well-regarded emperors of Rome’s 2nd-century C.E. golden age, Constantine was signaling that he intended to model his rule after earlier, successful leaders.