The subject sprawls on a blue chair in this painting that challenges assumptions about childhood and perspective.

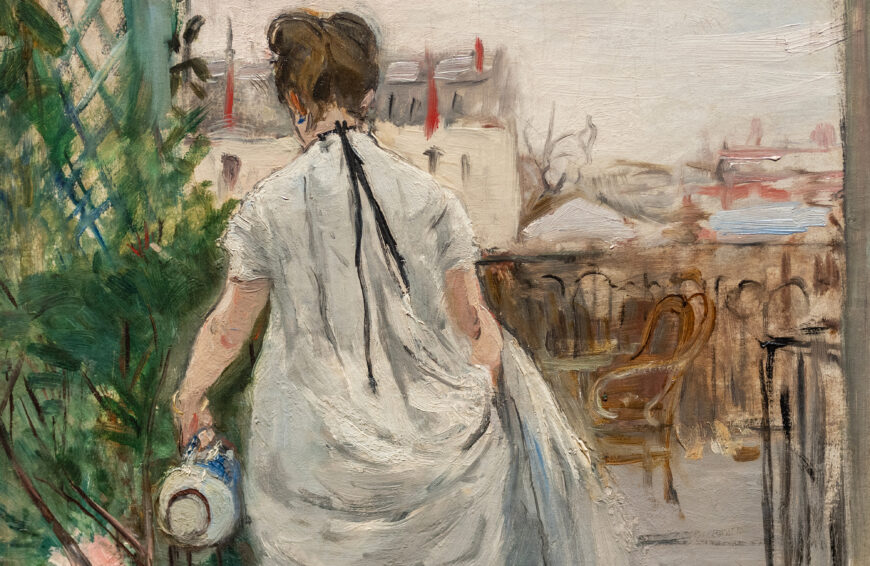

Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

0:00:05.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., looking at Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair. This is a magnet in this gallery. People are drawn to this painting, and I think it’s because it’s so expressive of a human feeling that children express but adults try not to.

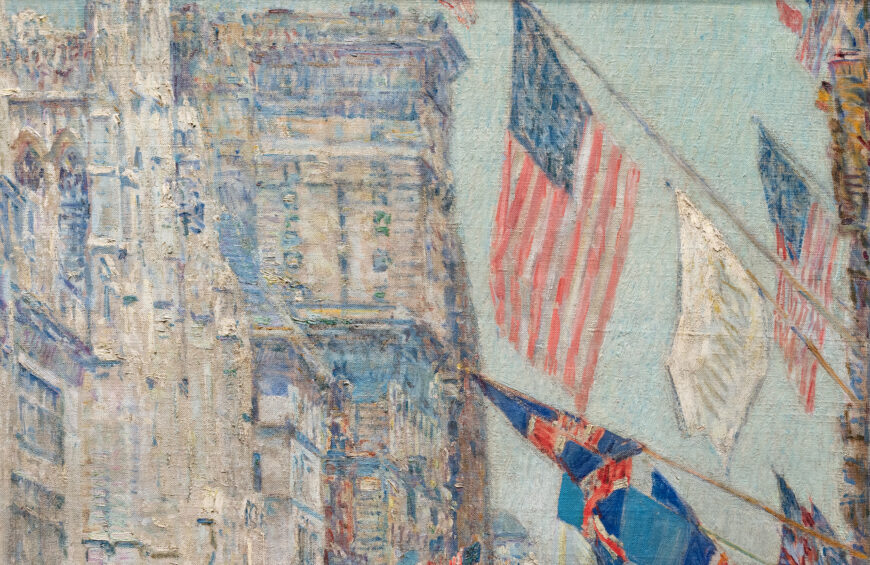

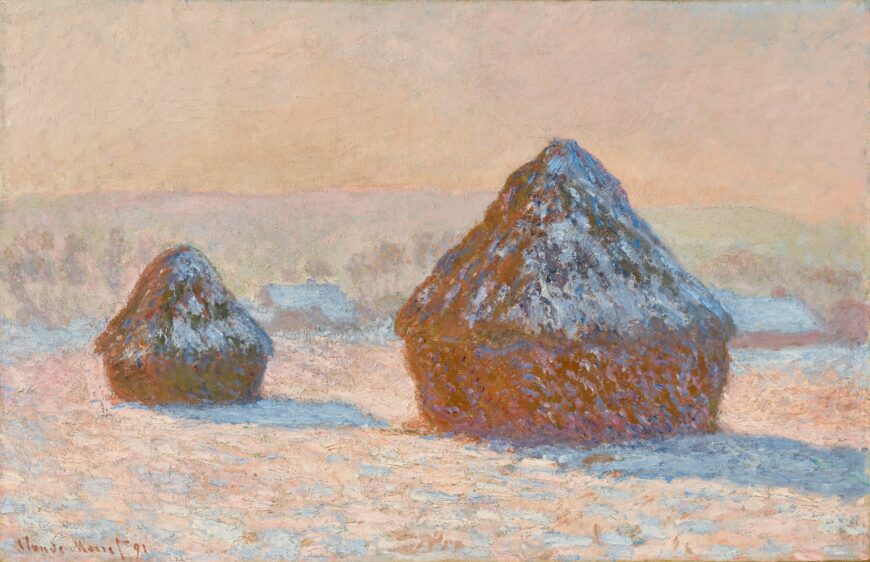

0:00:24.6 Dr. Beth Harris: This is a really interesting gallery that’s filled with the work of other Impressionists. We see Monet’s portrait of his son in a cradle and portraits of women by Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas and these scenes from modern life that are really typical of Impressionism. But this one really stands out.

0:00:46.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: The girl sits on the chair, but with a kind of almost defiance in her exhaustion.

0:00:52.1 Dr. Beth Harris: She does seem to have flung herself down on this large chair that emphasizes her childhood, her smallness.

0:01:00.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: But she’s actually quite large in this canvas. Her left toe seems to almost be trying to touch the frame of the painting, and the bow in her hair reaches very close to the top of the canvas. And so she’s occupying quite a bit of space. So we’re close to her, and it also suggests our vantage point, which is quite low. We’re at a child’s level looking across at her.

0:01:26.1 Dr. Beth Harris: I’m not really sure that we’re at a very precise point in space because in some ways I feel like I look down at her, and in some ways I look across from her, and in some ways I feel like I look down at that carpet. And she forms this very strong diagonal line on one side of the canvas. It’s very asymmetrical. We have this empty space on the left, this voluminous figure and chair on the right, and this tension between the surface pattern and the three-dimensionality of her body.

0:01:59.9 Dr. Steven Zucker: Well, you see this tension between flatness and volume everywhere. There is, as you said, that wonderful pattern that is part of the fabric of these chairs. You see the wonderful pattern of the tartan that she wears across her midsection and that is gathered up behind her shoulders and then in the bow in her hair as well.

0:02:18.6 Dr. Beth Harris: And in her socks too.

0:02:20.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: Oh, right, and in the socks. But that’s then all placed against a ground plane that on one hand does recede into space because the light from the window in the back of the room is illuminating the floor just a little bit. But at the same time, that floor becomes almost an abstract negative space that is absolutely flat and reminds us of the two-dimensionality of this canvas. And so there really is this play between two and three dimensions.

0:02:48.1 Dr. Beth Harris: And I think that the ambiguity of the space and our place within it is clear if we look at the carpet or that gray floor on the right side of the chair where it almost seems to come in front of the edge of the chair. And what is so shocking to me is the looseness of the brush strokes all over the blue pattern of the four chairs here. All of these quick squiggly lines of paint and I think, how did she decide it was done? Clearly what she was going for was this spontaneity, was this rapidity, was this sense of a ephemeral moment and not to have it look finished and careful.

0:03:27.5 Dr. Steven Zucker: I think that’s especially effective in the way in which Cassatt has handled the lace that she wears because it seems as if that lace is still in motion from the child having flopped down, that nothing yet is fixed, that she’s not yet at rest.

0:03:42.3 Dr. Beth Harris: The patterning speaks to me as does her dress and the neatness of her bangs of the adult grown-up world who’s dressed her up and gave her a kind of rigidity. And the patterns are all regular and she is this irregularity. She’s just had it with the grown-up world.

0:04:02.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: Well, she doesn’t fit. The chair is too big. Her feet don’t reach down to the floor. They’re not even close. But for me, there’s something else. She seems to be looking over at the dog and the dog is asleep and the dog is content in a way that she is not. And she seems almost a little jealous that the dog can be at peace and she’s not. She’s not comfortable. She’s not happy.

0:04:27.6 Dr. Beth Harris: Yeah, I’m not really clear that she’s looking at the dog. She could be, but she also could just not be. And Cassatt is offering these two figures to us for contemplation. But the dog, it’s true, he didn’t have to wear a bow. He doesn’t have to wear a dress. He doesn’t have to wear fancy Mary Janes. He doesn’t have to wear lace that you can’t get dirty. He’s unencumbered by the expectations of respectability of a kind of upper bourgeois class that Mary Cassatt belonged to.

0:04:56.6 Dr. Steven Zucker: It’s so interesting the way that the furniture stands in for the adult presence. The chair and the couch, especially in the background, seem almost as if they are an adult presence.

0:05:10.1 Dr. Beth Harris: I admit I’m just flabbergasted by some of the decisions that she made. Look at the girl’s right shoe and sock and how unfinished the paint around that shoe looks. She didn’t choose to resolve that at all, but there are some areas that are much more resolved like her right knee, for example, and calf. It’s just so interesting the way she decided, okay, this is done. And the blues and the shadows and greens and pinks in her flesh really confounding the expectations of a salon goer or of an exhibition goer in Paris in the 1870s. This looked like it was modern life. It looked modern in the way it was painted and in its subject matter.

0:05:55.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: One of the things that makes, I think, that modernity stand out is the composition’s asymmetry. The child is not in the center. This is almost a snapshot. This is a fragment of time. If we stand close to this and just look at these marks of pink and green and reds and whites, we’re seeing squiggles. We’re seeing gestural marks. We’re seeing a kind of pure abstraction on a field of blue. The furniture and its volumes vanish.

0:06:23.1 Dr. Beth Harris: It seems pretty clear to me that Cassatt, like so many other artists in the Impressionist circle, is looking at Velázquez, at this quickness of brushstroke that can give a feeling of light and of the everyday and capturing something in motion.

0:06:38.8 Dr. Steven Zucker: But they’re also looking at Japanese prints, which are helping to undo the linear perspective that had constructed space in the Western tradition for so long, and is giving license, in a sense, to create these tensions between volume and flatness, between space and two-dimensionality.

0:06:57.7 Dr. Beth Harris: And what we’re looking at is the work of a woman artist whose realm was primarily domestic spaces. And so with many of the male Impressionist artists, we’re looking at bars and cafes and the opera, but here, a child inside a fancy bourgeois drawing room.

0:07:16.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: Not just a child, I would say a modern child.

Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

A citizen of the world

If, as one art historian recently stated, Camille Pissarro was the glue that held Impressionism together, then Mary Stevenson Cassatt had similarly adhesive qualities. [1] Giving the lie to the stereotype that Americans were provincial—even barbarous—in their artistic tastes, Cassatt was anything but that; a cultured woman, educated in London, Paris and Berlin and fluent in French and German, she spent four years at the Pennsylvanian Academy of the Fine Arts before studying in France under Jean-Leon Gérôme, Thomas Couture and others.

Dog (detail), Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war she continued her travels, spending time in Italy and Spain, before settling in Paris once again in 1874, the year of the first Impressionist Exhibition. In the Salon of that year she exhibited a work that Degas, for one, admired. Over the following years, though, Salon success eluded her, largely, or so she judged, due to the prejudices of the all male selection jury.

It is understandable then that by 1877, when Degas invited her to join them, Cassatt would be drawn to this group of artists who were exhibiting independently and for whom gender did not appear to be a barrier for inclusion; certainly the quantity and quality of Berthe Morisot’s works in the first exhibitions were a match to those of the men. The same too can be said for the eleven paintings that Cassatt would exhibit in the fourth Impressionist Exhibition—included among them are some of her most celebrated paintings, notably Reading Le Figaro, Woman in a Loge, In the Loge and Little Girl in a Blue Armchair.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair

Produced in 1878, it shows a girl sprawled on a blue armchair in a room with three other chairs of a matching design. She stares at the floor unaware or unconcerned about the portrait that is being painted of her. On the chair opposite her a lapdog dozes, a dark patch that neatly balances the dark tones of her clothing. There are no tables or ornaments, nothing to offer the viewer or the girl, who appears tired and bored, any distractions, only two large windows that are closed and heavily cropped by the upper edge of the canvas.

Girl sprawled on blue armchair (detail), Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The dominance of the overstuffed furniture with its vibrant blue upholstery captures an odd sense of restlessness and languorousness, both matched by the girl’s pose. A parent would tell her to sit up properly and there is a rebellious, devil-may-care attitude in her comfortably lounging form. She has been dressed with due observance to fashion, the tartan shawl matching her socks and the bow in her carefully arranged hair; her shoes are spotless and the buckles sparkle; literally dolled up. All this primness however is of absolutely no concern to the girl whose unselfconscious pose presents as Petra Chu puts it: “a radically new image of childhood.”

Chairs (detail), Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

That a woman produced the image is, of course, no coincidence. The nursery in middle class homes was a space that was rarely if ever visited by men; child-rearing being an exclusively female occupation, little wonder then that few male artists painted babies or young children. But, of course, it is not in a nursery that we find ourselves, but a drawing room, clean to the point of sanitized, a room in which, just like her costume, the girl seems out of place, swamped by the massive abundance of chairs, a point emphasized compositionally in that each overlaps the other. The upshot of all this is to create a feeling—if not so extreme as alienation—then certainly a sense of disorientation, one that seems to capture, as subtly and incisively as any artist before her, the huffing and puffing tiresomeness a child feels within the social constraints of an adult’s world, a world that seems almost oppressively gendered.

Girl (detail), Chairs (detail), Mary Cassatt, Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878, oil on canvas, 89.5 x 129.8 cm (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The girl herself was the daughter of a friend of Degas’s and the painting is often cited as an example of Degas’s influence on Cassatt. The two certainly had much in common, if only in terms of their backgrounds. Both were born into the upper-middle-class, the children of bankers, and both had strong connections to America, Degas’s mother and grandmother were American and he had stayed with his family in New Orleans in 1872–73.

The similarities in their work, certainly in this period, are also striking. In its asymmetrical composition, the casual, unposed treatment of the sitter, the weightiness and solidity of its forms in contrast to that grey mercurial dollop of negative space, its use of cropping and loose brushwork, as well as the interest in the private moment that we find so often in his pastels, the hallmarks of Degas’s work can clearly be found in Little Girl in a Blue Armchair.

Japanese prints

The influence of Japanese prints is also a shared feature. Notice how in Degas’s famous L’Absinthe our eye is led in and up through the opposing diagonals of the marble-topped tables which seem almost to be floating. A similar effect is created by Cassatt in the blue furniture, to such an extent that we are left uncertain whose point of view we are looking from—a child’s at eye level or an adult’s from above. The composition, however, still coheres, the space and its various junctures having been carefully conceived to create a balanced whole.

Edgar Degas, L’Absinthe, 1876, oil on canvas, 92 x 68 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

These startling similarities may be accounted for by the fact that Degas had a hand in painting the background, a practice that seems shocking today. Cassatt seemed not to mind, though, writing several years later of how Degas “advised me on the background, he even worked on the background.” The last part she underlined suggesting that she even considered it a privilege. It was common practice for male artists to take a patronizing approach to their female counterparts. “Manet sermonizes me”, Berthe Morisot complained to her sister Edma. It is inconceivable, however, to think that either Degas or Manet, whose influence is certainly in evidence in Cassatt’s lavish use of cobalt blue and in the tonal treatment of the girl’s legs, would or could have painted such an image.

The splendid legacy

Like Manet and Degas, Cassatt spent time in Italy copying the great works there, including, in her case, those of Correggio. Perhaps there is something of that old master’s dreamy bambini in the pose of the little girl too. Either way, running alongside her distinctly modern artistic vision, the classical tradition she was trained in is never far away. She could be quite snobby about it in fact. She thought little of Paul Durand-Ruel, for instance, the greatest of the Impressionist dealers, for knowing next to nothing about Italian art. This did not put her off providing him with contacts when he traveled to New York with Impressionist works, including two of her own, which he exhibited in the spring of 1886. “Had it not been for Durand-Ruel, caviar would have been a good deal rarer,” Renoir once said to his son.

Yet, in the international success story of Impressionism, Cassatt is also owed her due. For among the contacts she gave Durand-Ruel was the sugar magnate Henry O. Havemeyer, whose wife Lousine was a close friend of hers, having studied art together in Paris. As the couple’s artistic consultant for the rest of her life Cassatt played a central role in the development of one of the greatest private collections ever amassed in America. Today New York’s Metropolitan holds hundreds of paintings bequeathed by the Havemeyer family, including, the Museum claims, “the most complete group of Degas’s works ever assembled” and twenty works by Mary Cassatt, a woman remarkable not only for helping shape contemporary tastes in American connoisseurship, but also, over the course of her long artistic career, for producing work of extraordinary quality that helped transform American art itself into a world-class enterprise.