Hazy with smoke, the architecture of the train station and technology of the iron engine dissolve before our eyes.

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare (or Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), 1877, oil on canvas, 75 x 104 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the Musée d’Orsay, looking at Monet’s canvas, “Gare Saint-Lazare.” This is one of several large train stations in the city of Paris. It’s really interesting that we’re looking at it in the Musée d’Orsay, which is a renovated train station itself.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:19] We think about train stations as just an ordinary part of urban life, but in the late 19th century in Paris, large train stations carrying masses of people out to the suburbs, out to vacation spots, these are new kinds of structures.

Dr. Zucker: [0:33] They express their modernity not only through their function but also through their architecture. Trains at this point were powered by burning coal and creating steam, and that required large, open sheds, which were held aloft by iron, all of which spoke of modernity.

[0:48] This was not the traditional architecture of wood or of stone. This is a completely modern subject.

Dr. Harris: [0:54] This space looked modern, and it’s not just the train shed but the apartment buildings that we see beyond it that looked new. During the second half of the 19th century, Paris was rebuilt.

[1:05] The old, winding, maze-like, congested streets were torn down, and wide boulevards were built with apartment buildings housing cafés and department stores, catering to a new middle class, an upper middle class that had cash to spend, and the time and leisure to shop and to enjoy themselves in Paris.

Dr. Zucker: [1:27] In a subtler way, the idea of transportation itself, the idea of a place where people of different classes mix is also itself modern. For so long, French society had been rigidly ranked, but that’s unraveling in the modern era, and perhaps nowhere more vividly expressed than in a public space like the train station.

Dr. Harris: [1:46] We often think about Impressionist painting as being about leisure. Renoir’s “Moulin de la Galette,” for example, where we see figures socializing and dancing.

Dr. Zucker: [1:54] This is a working space, but look at the surface of this canvas. It’s absolutely luscious. It’s so drenched with steam and light and smoke that it seems to almost dissolve before our eyes.

Dr. Harris: [2:05] It’s difficult in some places to make out the architecture of the train shed because that steam hides it, especially on the left, where those bluish-lilac puffs of steam obscure that iron framework.

Dr. Zucker: [2:18] Light is pouring through the opening at the top of the shed, creating this prism of color that is playing across the steam within. In fact, one critic humorously said, “I can’t really see the paintings for all the smoke that’s emanating from these six canvases that Monet exhibited together, each a play on this subject.”

Dr. Harris: [2:36] And it’s not only the architectural structure that’s disappearing, but the forms of the trains themselves. These are big machines that dissolve into light and atmosphere.

Dr. Zucker: [2:47] Well, that’s what Monet is interested in, pure color and pure light in the optical play before him, rather than his empirical knowledge of the solidity of an iron engine.

Dr. Harris: [2:57] We have to remember that the Impressionists were positioning themselves outside of the academic establishment. This painting and the group of other paintings of La Gare Saint-Lazare were exhibited at an Impressionist exhibition, which was independent of the official exhibitions called Salons that were sponsored by the Royal Academy.

[3:13] And so, Monet is not giving us a painting that would be a view of La Gare Saint-Lazare, with a factual accounting of what was in this station and what one knows of it, but you’re right, this optical experience of light and atmosphere, this very subjective experience.

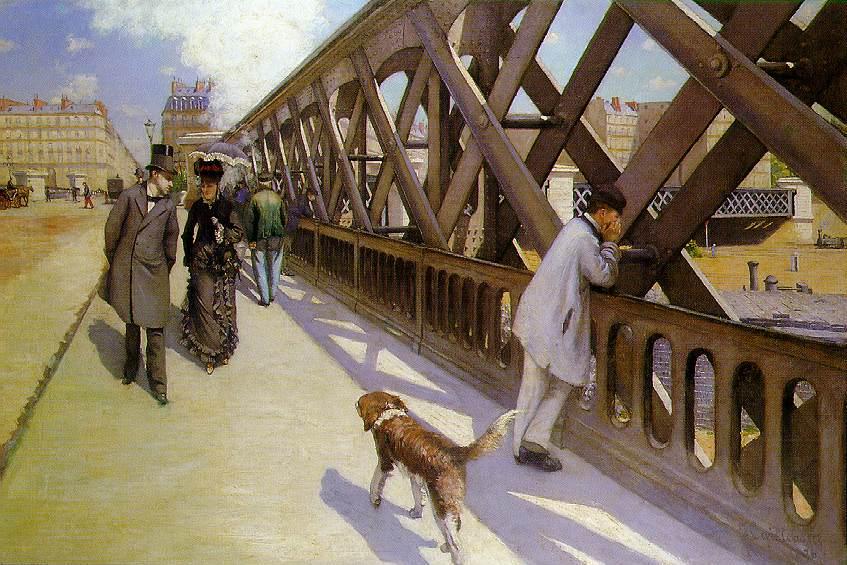

Dr. Zucker: [3:29] Monet was not the only person in his group that was interested in this subject. Manet had painted this subject, although in a very different way. Another important artist, Caillebotte, had painted a scene from the bridge that we see just beyond the smokestack of the locomotive.

Dr. Harris: [3:43] What fascinates me too is the degree to which Monet has reduced the figures themselves to quick brushstrokes. We can’t make out faces. We can make out a little bit of gestures or postures, but he’s really reducing the human figure to these quick strokes of paint.

[4:00] The human figure was the centerpiece of academic painting, and yet here it becomes equal to the trains and to the architecture he’s painting.

Dr. Zucker: [4:09] And subservient to the main subject of this painting, light and color.

Dr. Harris: [4:13] Other Impressionist artists like Renoir will concern themselves with the human figure within the light and atmosphere, but for Monet, it is the landscape, and here an urban landscape, that is most important to him.

[4:25] Critics like Baudelaire had been calling for artists to paint the beauty of modern life, and I think with paintings like “La Gare Saint-Lazare,” Monet is taking up that challenge. Artists didn’t need to paint classical antiquity anymore. They didn’t need to paint biblical and history paintings.

Dr. Zucker: [4:41] They were creating a new beauty that was true to the new modern world in which they lived. For all our talk about the sense of spontaneity, if you look at the surface, this is a heavily worked canvas.

[4:52] Monet seems to be weaving color across the surface. You can see the paint has built up over time. There’s no atmospheric perspective. The atmosphere is in the foreground as well as in the background, all of which makes it impossible for us to forget that we’re looking at paint on canvas.

Dr. Harris: [5:07] Monet and the Impressionists are creating a new visual language for a new modern world.

[5:13] [music]

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare (or Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), 1877, oil on canvas, 75 x 104 cm (Musée d’Orsay, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monet’s painting, The Gare Saint-Lazare, overwhelms the viewer not through its scale (a modest 29 ½ by 41 inches), but through the deep sea of steam and smoke that envelops the canvas. Indeed, as one contemporary reviewer remarked somewhat sarcastically, “Unfortunately thick smoke escaping from the canvas prevented our seeing the six paintings dedicated to this study.”[1]

The Gare Saint-Lazare (also known as Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), depicts one of the passenger platforms of the Gare Saint-Lazare, one of Paris’s largest and busiest train terminals. The painting is not so much a single view of a train platform, it is rather a component in larger project of a dozen canvases which attempts to portray all facets of the Gare Saint-Lazare. The paintings all have similar themes—including the play of light filtered through the smoke of the train shed, the billowing clouds of steam, and the locomotives that dominate the site. Of these twelve linked paintings, Monet exhibited between six and eight of them at the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877, where they were among the most discussed paintings exhibited by any of the artists.

Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train, 1877, oil on canvas, 83 x 101.3 cm (Harvard Art Museums)

Light and steam

Light—the dominant formal element in so many Impressionist paintings—is given particularly close attention in The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line. Here, as in many of the Impressionists’ most celebrated paintings, Monet shows a bright day and labors to reproduce the closely observed effects of pure sunlight. The billowing clouds of steam add to the effect, creating layers of light that fill the canvas. Here however, we must pause as The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line is an exception within the full group—it is one of only two paintings of the train station shown on a bright bright, sunny, day. In contrast, the other ten paintings (for example the one at the Harvard Art Museums, above) show dark, hazy views of the Gare Saint-Lazare. Though an exception and anomaly in terms of its interest in sunlight, The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line shares a great deal in common with the other paintings at least in terms of subject and view.

Apartment buildings in the distance (detail), Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare (or Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), 1877, oil on canvas, 75 x 104 cm (Musée d’Orsay, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monet’s achievement is extraordinary, and The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line has rightfully been singled out as among the most impressive paintings of Impressionism. Monet renders the steam with a range of blues, pinks, violets, tans, grays, whites, blacks, and yellows. He depicts not just the steam and light—which fill the canvas—but also their effect on the site—the large distant apartments, the Pont de l’Europe (a bridge that overlooked the train station), and the many locomotives—all of which peak through, and dematerialize into a thick industrial haze.

Train and shed as subject

Against the bright background, Monet represents the station’s vast iron roof in copper and tan tones that stand out against The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line’s low key palette, with its swirling blue, gray and purple background. The trains—here represented by no less than three locomotives and a large box car—are shown as both the source of the steam and distinct from it. However, in 1877, a number of critics were worried the smoke would completely engulf them. Gorges Maillard, writing in the conservative journal Le Pays, made just this point, describing the paintings as “the rails, lanterns, switchers, wagons, above all, always these flakes, these mists, clouds of white steam, are so thick they sometimes hide everything else.”[2]

Locomotives and tracks (detail), Claude Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare (or Interior View of the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line), 1877, oil on canvas, 75 x 104 cm (Musée d’Orsay, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line and the other paintings of the Gare Saint-Lazare by Monet are hardly an isolated moment in the artist’s oeuvre. In the 1870s Monet—along with most of the other major Impressionists including, Caillebotte, Pissarro, Renoir, Degas, Guillaumin, Raffaëlli, and even Manet—had shown a steady interest in the railroad as a subject within their paintings of modern of life. In fact, the six to eight paintings Monet exhibited at the Third Impressionist Exhibition were shown along with Caillebotte’s monumental Le Pont de l’Europe (below) that likewise shows the train yards of the Gare Saint-Lazare. Caillebotte’s painting though shows the site from the great iron bridge that crossed over the yards—the Pont de l’Europe. Interestingly, Caillebotte’s painting of genteel strollers set in the bourgeois world of Paris’s grand boulevards drew praise, while Monet’s paintings of trains, steam and industrial activity were severely criticized.

Perhaps the criticism is due to the fact that Monet shows the locomotives as the main subject, rather than as background elements. He shows them unapologetically, in their natural element, among the steam, workers and activity of the bustling train station. Four paintings in the set of twelve, including The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line, show the large and distinctive cast iron spans that covered the platforms. However, the other paintings show the exterior, the yards, workers, tunnels, switches, sheds, and engines of the station. Indeed, even in The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line and the other so-called interiors of the of the train shed, Monet includes workers, steam, and industrial machines. In fact, what he does not show is the grand hotel, lavish entrance or sculpture of the station’s impressive façade. Even in the interiors, the paintings are very much the business end of the station.

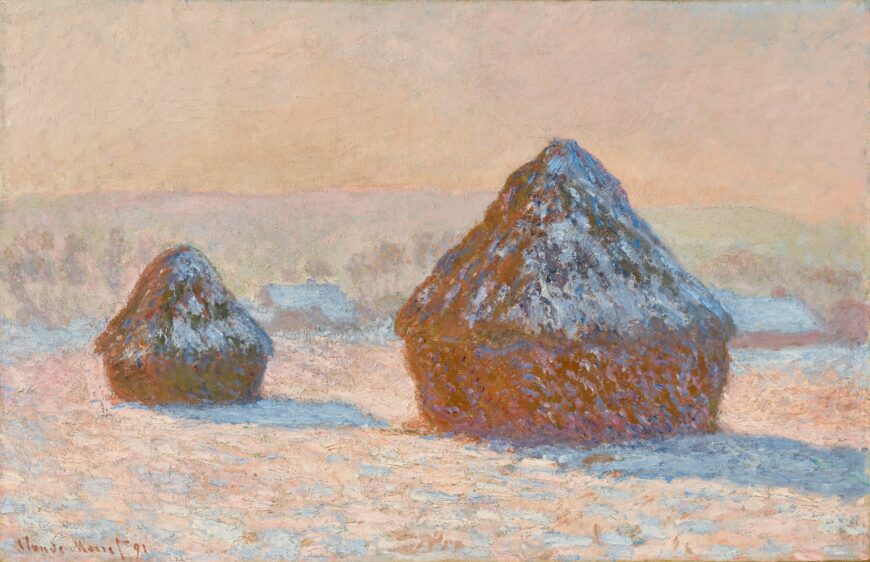

A series?

These common subjects—train, steam, and industrial activity—raise the question of whether the works should be regarded as series. Though scholars have frequently discussed the works, and particularly the four interiors, as part of series, only two of the works show a repeated (or serial) view. When taken as a whole the group does not seem to be the manifestation of an interest in serial painting or an exploration of subtle changes only evident in repeated views (as Monet will later do with his series of grain stacks) bur rather as an effort to capture the varied aspects of the station by rendering its many faces in paint.

In The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line Monet shows his keen interest in light, color, and paint handling, yet The Gare Saint-Lazare, the Auteuil Line cannot be divorced from its subject—the locomotives, the steam, and the yard of the Gare Saint-Lazare. In this bright scene Monet gives us a new vision of modern life that does not shy away from its industrial side.