Mesoamerica: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 32

Mesoamerica and the Caribbean, 900–16th century

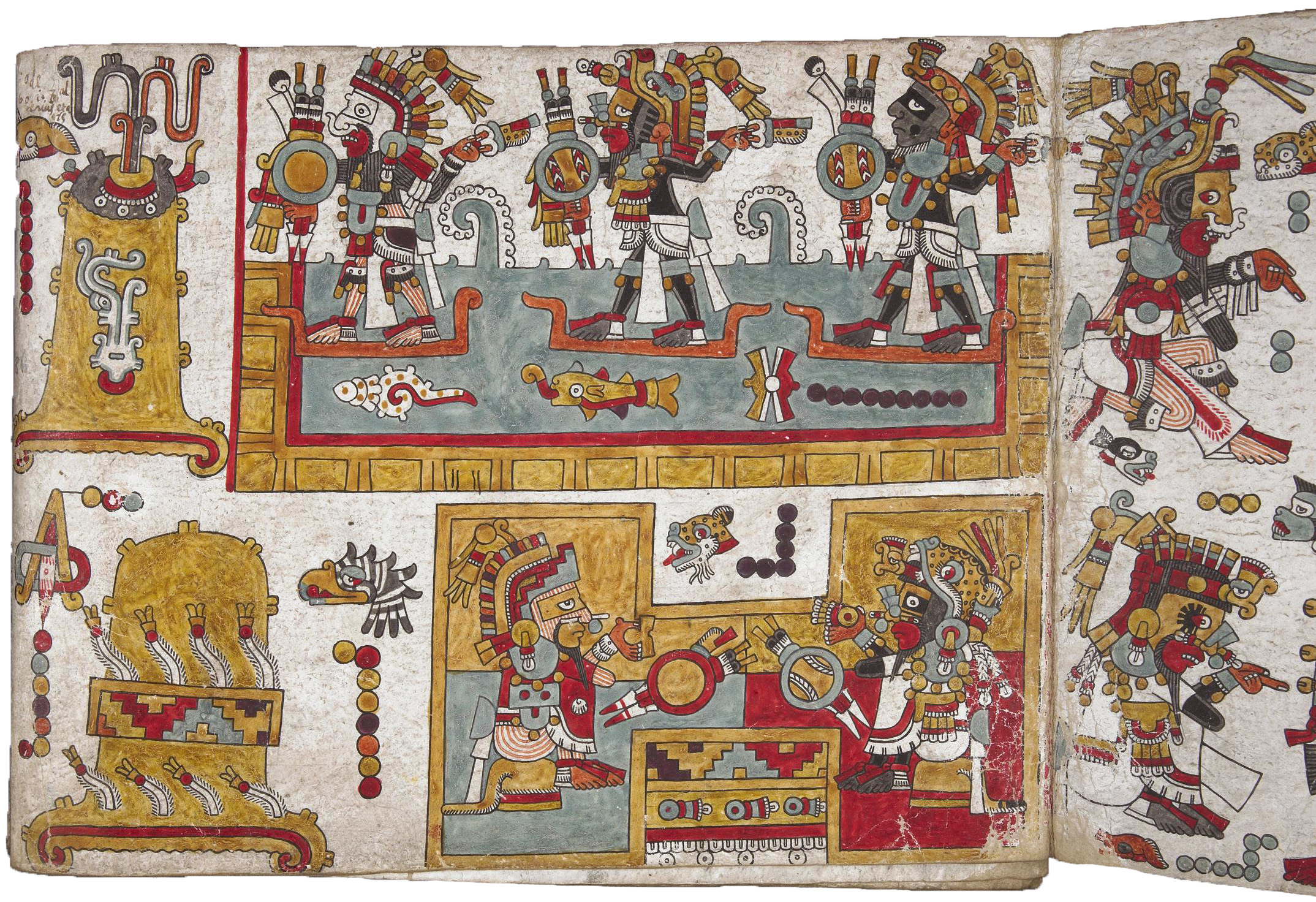

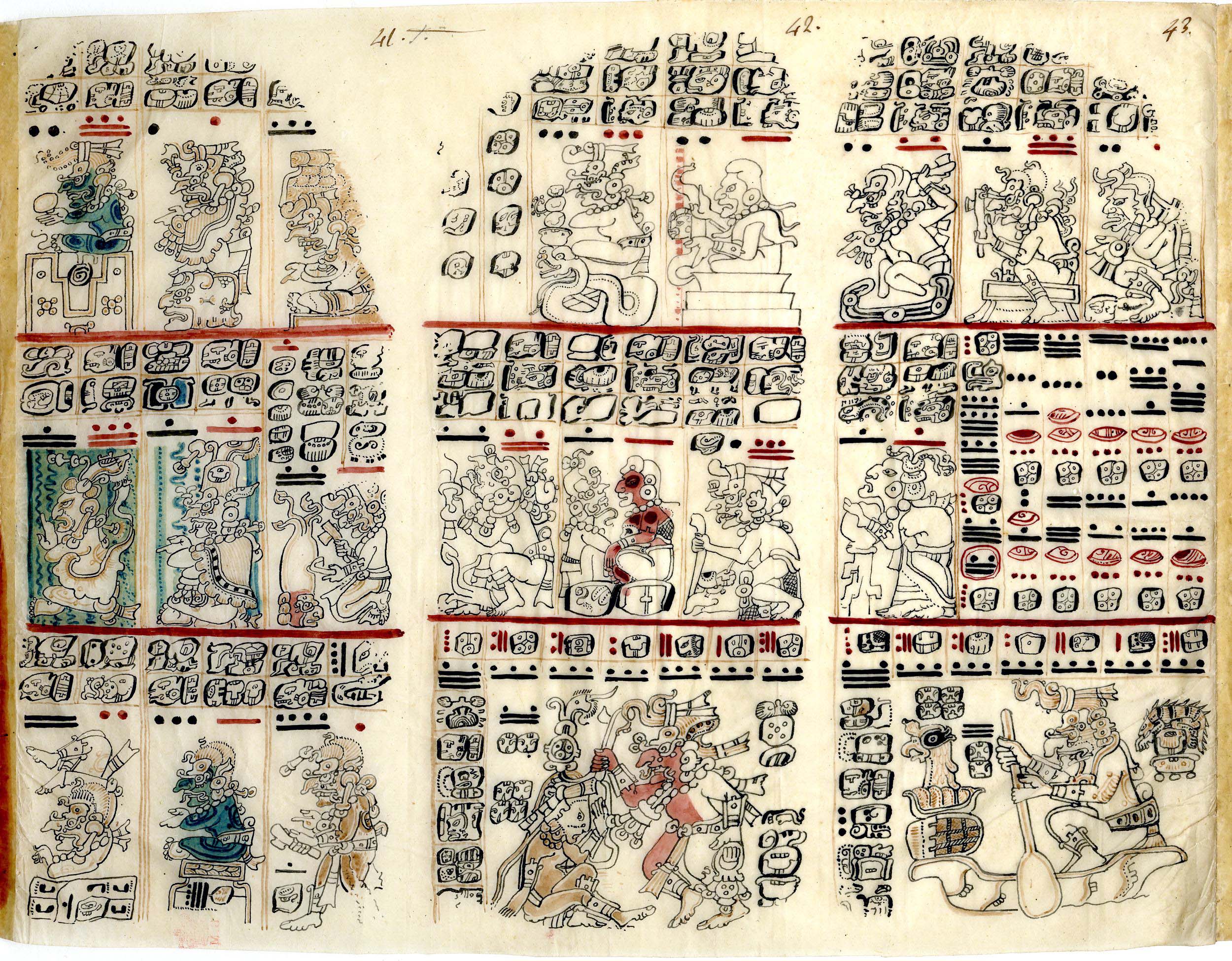

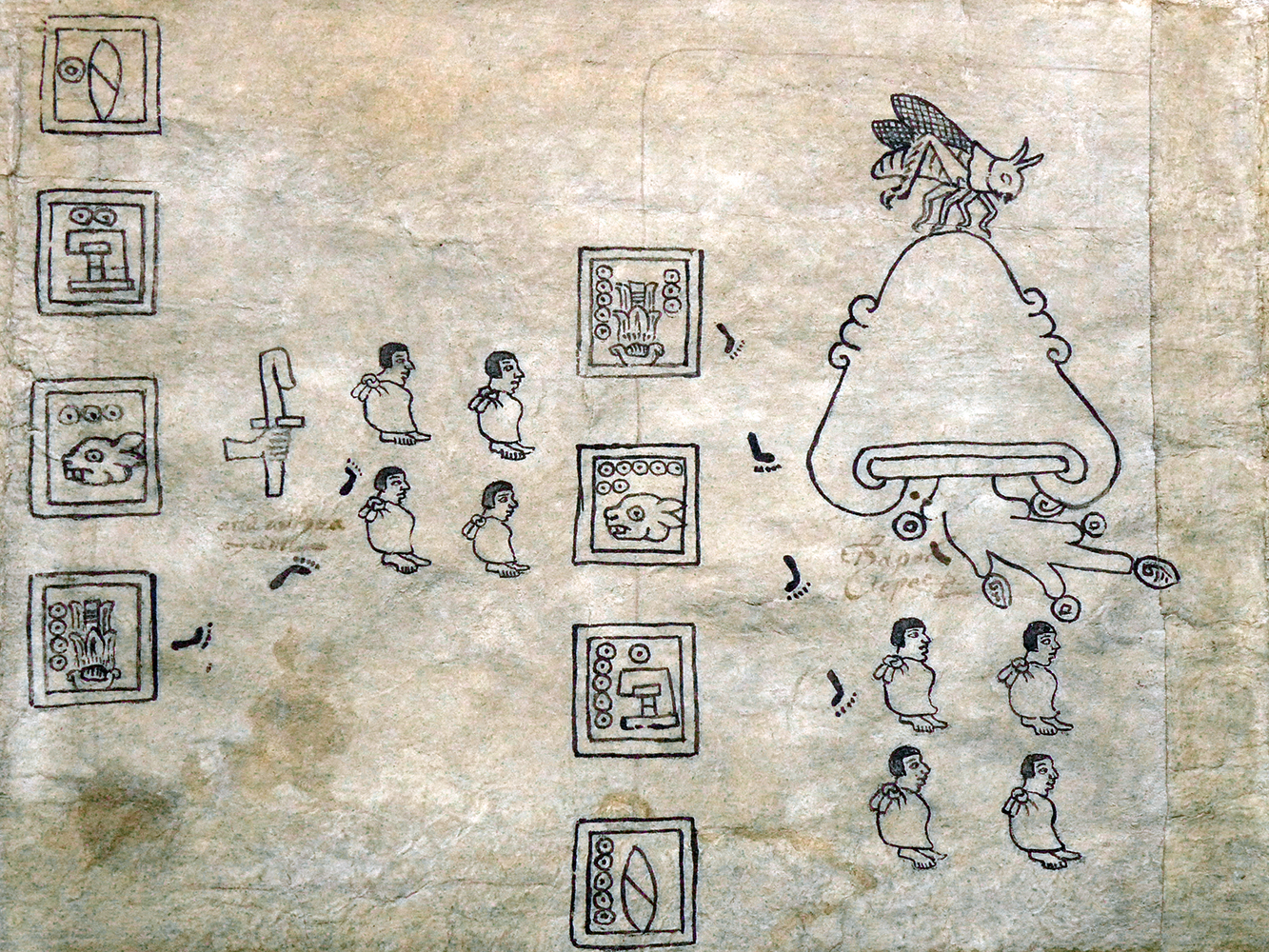

In part, the codex chronicles the life of Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. Here, we see figures traversing water and sitting in an I-shaped ballcourt—all dressed in sumptuous clothing. Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 1200–1521, C.E., Mixtec (Ñudzavui), Late Postclassic period, deer skin, 47 leaves, each 19 x 23.5 cm, Mexico (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Between 900 and 1521 C.E., the diverse peoples of Mesoamerica created works of art and architecture that both built on and diverged from the traditions established by their ancestors. In this chapter, we will consider art produced by Aztec, Huastec, and Taíno artists, from books to temples to religious figurines. The chapter ends with the Spanish invasion, and the monumental—and devastating—changes it wrought across the area. The period from 900 to 1521 C.E. is generally referred to as the “Postclassic” period.

Map of Postclassic Mesoamerica and the Caribbean (underlying map © Google)

Mesoamerica is a cultural region that spans what is today Mexico to northern Costa Rica. In this area, cultures shared a number of important features, including maize agriculture, a 260-day ritual calendar, and ballgames. Cultures of the Caribbean demonstrate some similarities with Mesoamerican groups, like the ballgame, but had limited contact with Mesoamerica.

While some overarching themes connect different groups, it is important to emphasize the diversity of this region. In this period, people in thousands of cultural groups made works of art that reflected their beliefs and practices. The art and architecture that survives today represents a small fraction of the works produced by ancient makers.

This chapter addresses five themes:

- the tradition of bookmaking

- the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan

- the use of diverse media

- ancestors and supernatural forces

- the Spanish invasion of the Americas

One of the most impressive buildings at Chichén Itzá is the nine-level structure most commonly known as El Castillo. It was devoted to Kukulkan, the Maya feathered serpent deity. Temple of Kukulcan (also known as El Castillo), 8th–12th century, Chichén Itzá, Mexico (photo: Pascal, CC BY 2.0)

900 C.E. was a time of change in Mesoamerica. In the Maya region, people were in the process of adapting to new cultural circumstances following the collapse of many Classic-period cities (such as Palenque or Yaxchilán). Powerful new centers like Chichén Itzá and Mayapan were emerging.

Located in the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley, in the central Mexican highlands, Cholula became an important city in Mesoamerica between 1200–1521. It is known for its beautiful polychrome ceramics, particularly dishes, bowls, and vases. They show a clear influence from the Mixteca (modern states of Oaxaca and Puebla) and the Gulf Coast regions. Mixteca-Puebla pottery vessel, c. 1300–1521, from Cholula, Puebla, Mexico, 12.8 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

In Central Mexico, a number of cities flourished in this period (such as Cholula) before the arrival of the Aztec in the region around 1300 C.E. The Aztec (they called themselves the Mexica, but we will use the term “Aztec” here for clarity) quickly established themselves as a regional power and eventually constructed an enormous empire based in Tenochtitlan (today known as Mexico City).

Shell ornaments, copper bells, rubber balls, and macaws are only some of the remarkable finds from the archaeological site of Paquimé (also known as Casas Grandes) in northern Mexico. Some of these things traveled on long-distance trade networks that ran from southern Mesoamerica to what is now the southwestern United States, and west to the Gulf of California. Here, we see macaw pens; macaws had to be traded from southern Mesoamerica, and they were also bred at Paquimé. Turquoise was traded from the southwest further into Mesoamerica—as we see with the mosaic objects shown later in this chapter. Macaw pens, Paquimé (Casas Grandes), c. 1150–1350 C.E., Chihuahua, Mexico (photo: DiSchamelrider, CC0)

While the Aztec are perhaps the best known, cultures throughout Mesoamerica and beyond, including the Mixtec (Ñudzavui), Huastec, and Taíno, produced important works of art in this time period as well. Robust trade networks in this era facilitated the movement of people and ideas—so much so that, when combined with political changes, it can be hard to identify exactly who produced what objects.

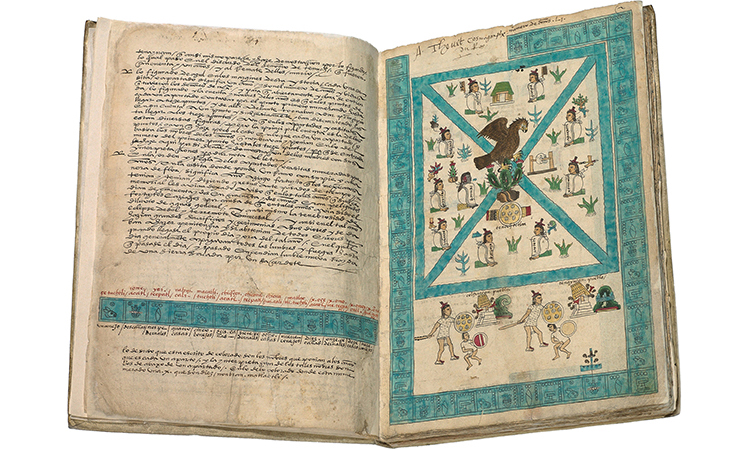

Codex Mendoza, Viceroyalty of New Spain, c. 1541–42, pigment on paper © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

As we look through this material, keep in mind how we are getting our information. Unlike in the Classic period (c. 200–900 C.E.), there is limited use of hieroglyphs in the Maya area, and few Indigenous books have survived from Mesoamerica. Substantial information about the Aztec comes from sources compiled after the Spanish invasion by both Spanish and Indigenous authors and illustrators. As a result, we should be aware of bias in records that date to the colonial era. A robust program of archaeology throughout the area, combined with renewed attention to Indigenous historical accounts of the invasion and its aftermath, has provided a new window into the Indigenous past.

The following essays provide more information about Mesoamerica, the Mesoamerican calendar, and the time periods scholars use to study Mesoamerican art history. Other essays introduce the Aztec (Mexica) and Taíno.

Read and watch these introductory materials

/5 Completed

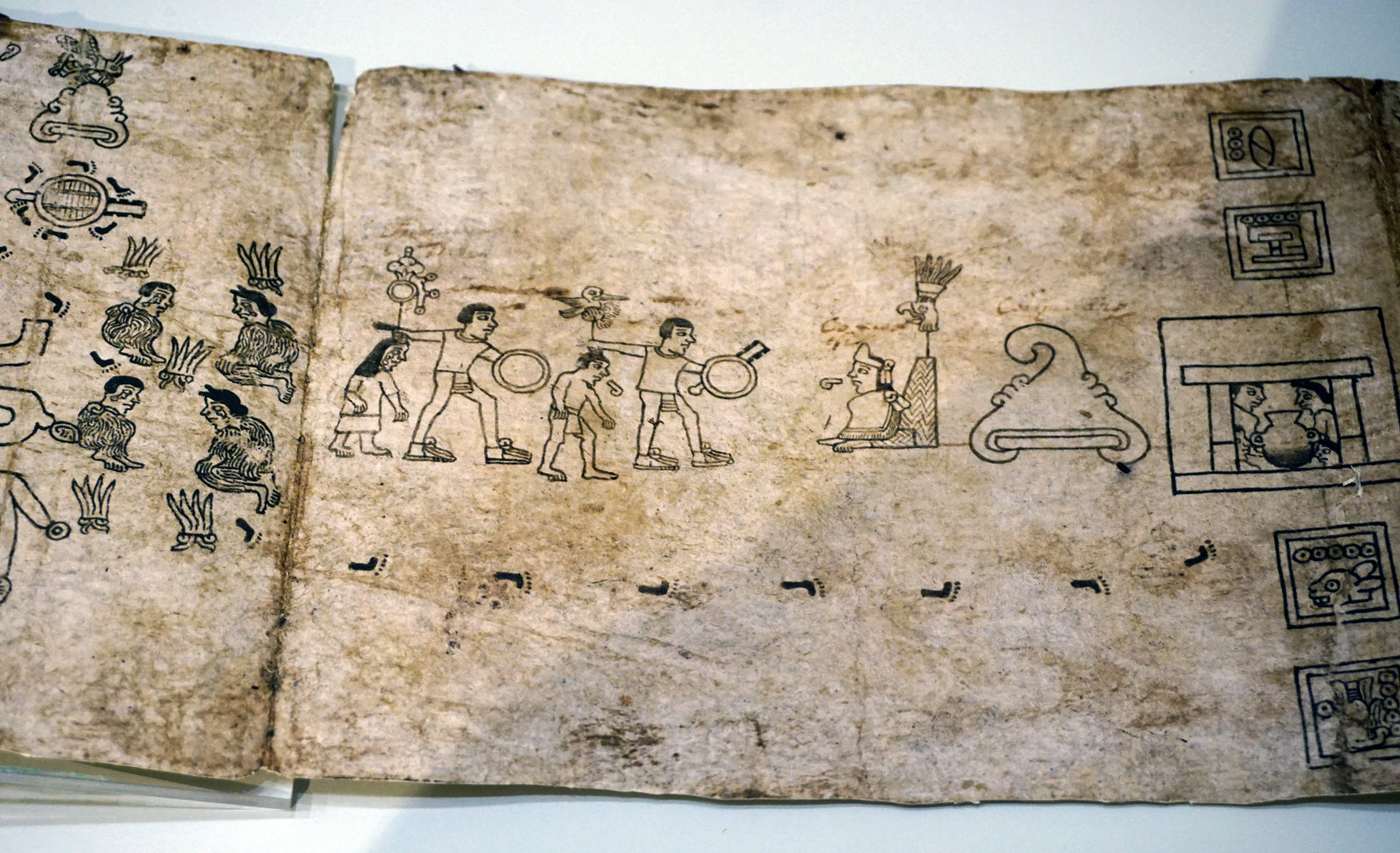

Books

Codex Boturini, early 16th century, 19.8 x 549 centimeters (single pages are 19.8 x 25.4 centimeters), ink on amatl paper, Viceroyalty of New Spain (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City, Photo: xiroro, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The tradition of bookmaking in Mesoamerica probably began long before 900 C.E., but most books have not survived. Only a few books from the Postclassic and early colonial periods remain today. This is in part because paper does not preserve well in the archaeological record, but also because of the systematic destruction of books by the Spanish. The few surviving books from the Aztec, Mixtec, and Maya tell us about how Indigenous Americans conceived of their world. As far as we know, there was no bookmaking tradition in Taíno culture.

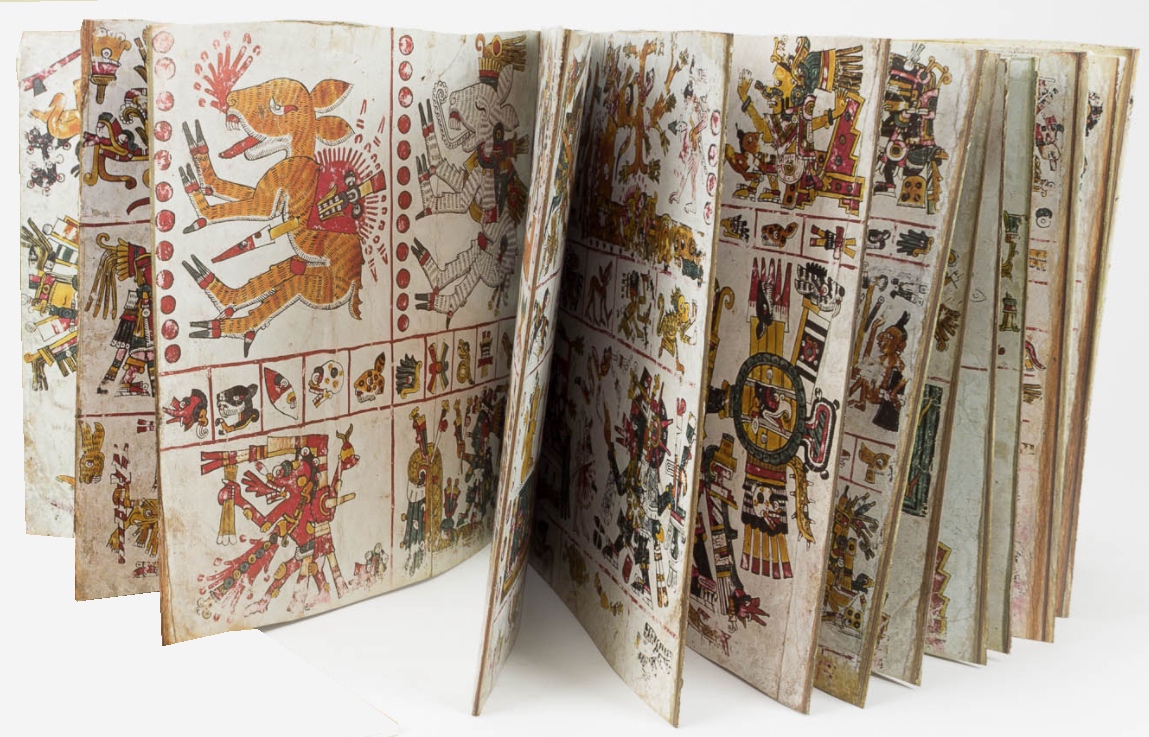

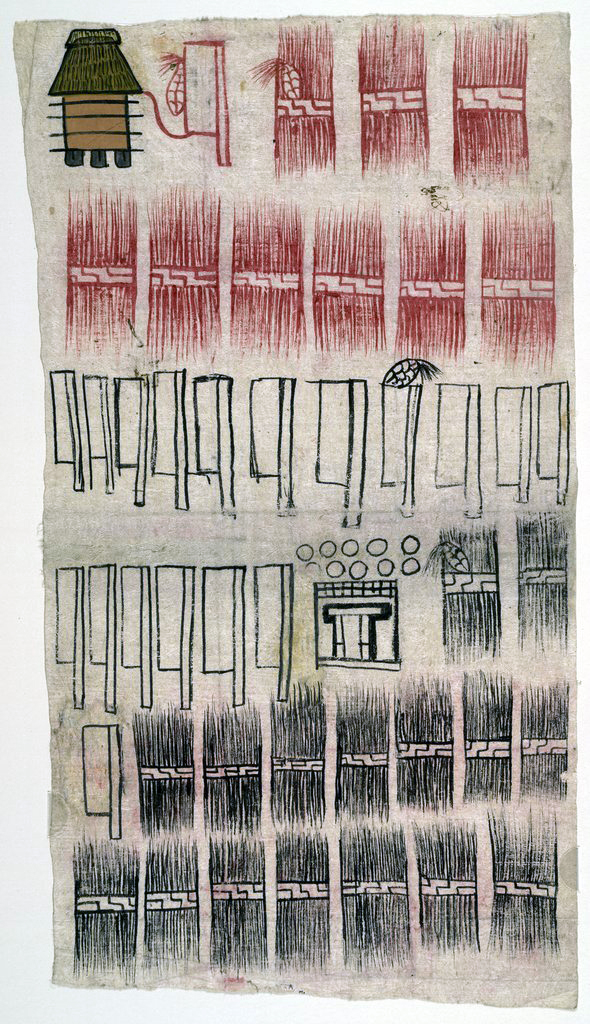

Codex Borgia, facsimile edition published by Testimonio Compañía Editorial, 2008

Mesoamerican books are often called codices (singular: codex) or manuscripts, and they could be made of deerskin or bark (amatl) paper. These books are referred to as “screenfold” books because they fold like an accordion rather than being bound in the middle like their European counterparts (look at the Aztec Codex Borgia above, for instance). The screenfold method allowed for books to be performed as well as read from front to back: imagine folding out just the pages you want to talk about, for example, so that an audience could see them. These books recorded information about religion, politics, history, and the natural world. Artists used both visual cues and hieroglyphs to identify people, places, things, and events. While some of these books were created after the Spanish invasion, they address Indigenous lifeways that predate the arrival of Europeans.

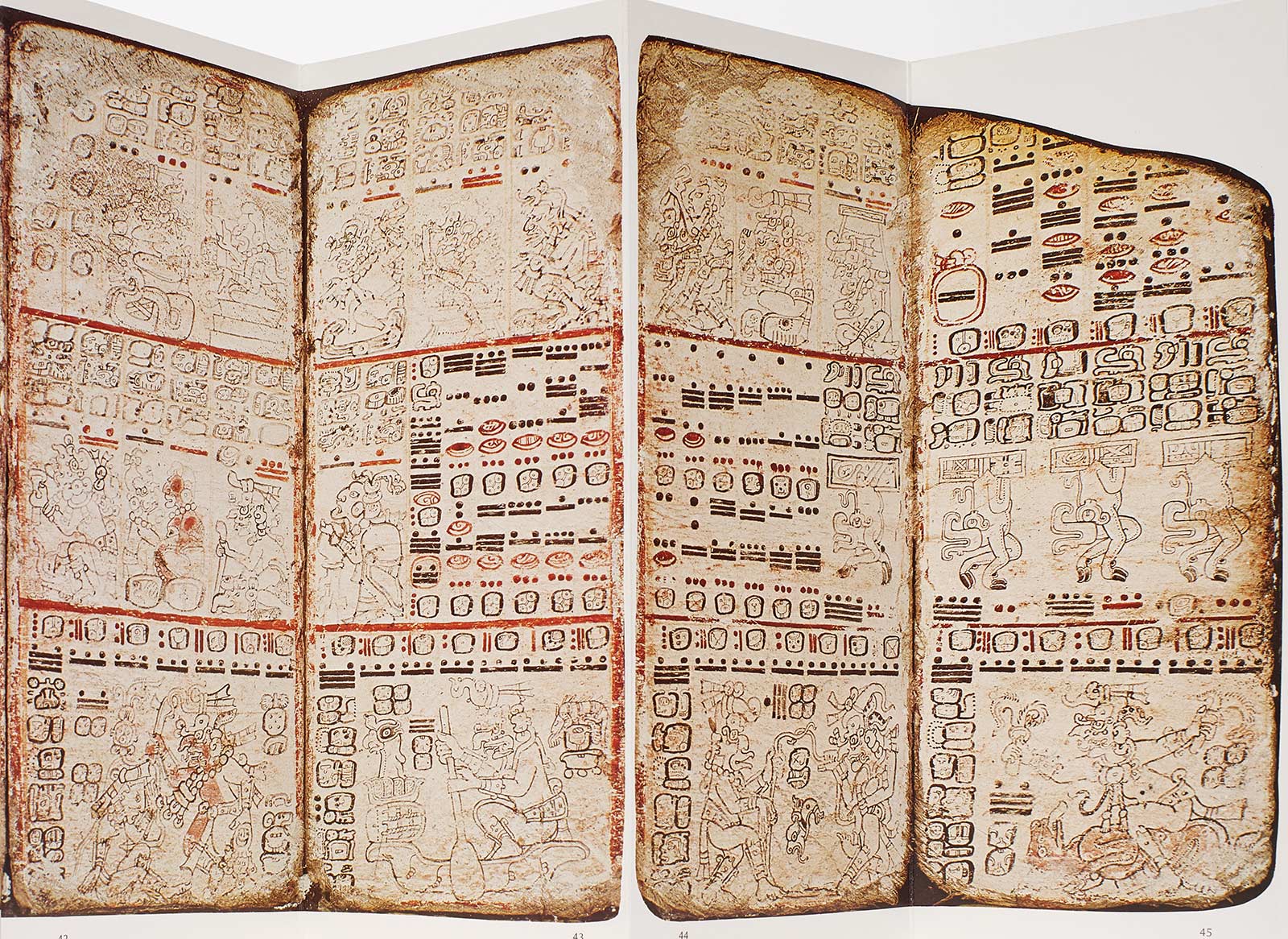

Facsimile of the Dresden Codex (detail), c. 1200–1500, made in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico (Dresden, Germany, Saxon State Library, Mscr.Dresd. R 310. The Getty Research Institute, 2645-271)

Maya scribes probably created the Dresden Codex at some point between 1200–1500 C.E. The 74-page screenfold codex is made of bark paper, and its pages are covered in a fine layer of stucco. It may originally have had wooden covers. Images with human figures and hieroglyphic writing adorn the pages.

Facsimile of the Dresden Codex (detail), c. 1200–1500, made in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico (Dresden, Germany, Saxon State Library, Mscr.Dresd. R 310. The Getty Research Institute, 2645-271)

The writing includes information related to the 260-day calendar, passages about the movement of the stars and planets (like Venus), prophecies about the future, and rituals involving various gods, including the Moon Goddess and Chahk (the rain god). The book may have been copied from a previous edition (much like the copying of manuscripts in medieval Europe), and it is one of the oldest surviving books from the Americas. Very few precolonial books have survived.

As you read the essays below, what comes to mind when you think of the word book? How do Mesoamerican books adhere to or differ from your idea of a book?

Read essays about books

Painting Aztec History: The Aztecs understood writing and painting to be deeply intertwined processes.

Read Now >

Codex Borgia: Thirty-three feet long, the Aztec Codex Borgia records historical, ritual, mythological, and botanical information.

Read Now >

Codex Zouche-Nuttall: This Mixtec codex records the life and times of ruler Eight Deer Jaguar-Claw.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Tenochtitlan

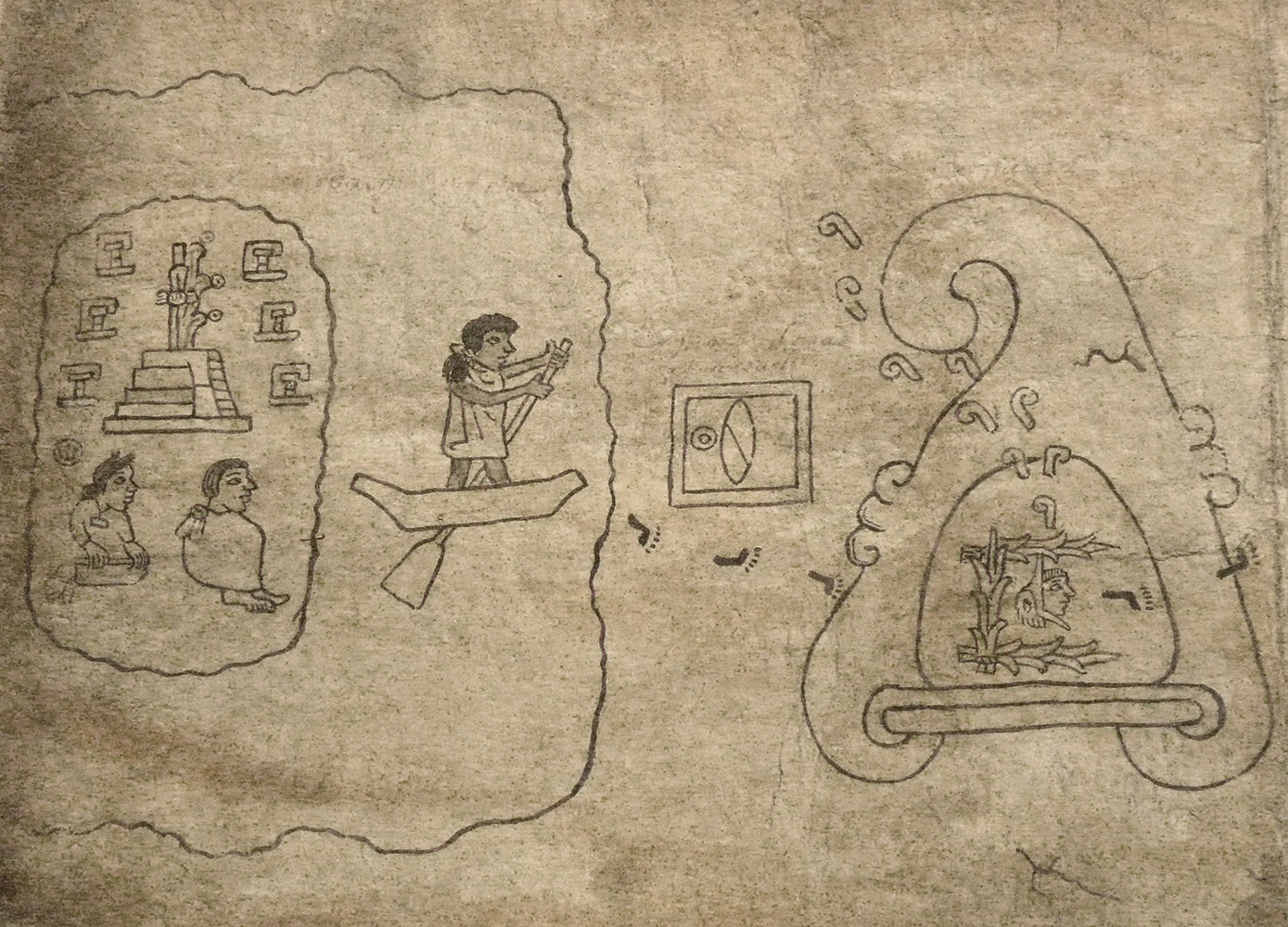

The first page of the Codex Boturini represents the beginning of the Aztec migration story, the story of the Aztecs’ journey from their ancestral homeland called Aztlan to their arrival at the eventual capital of their empire, Tenochtitlan (today, Mexico City). Here, a figure in a canoe departs from an island in the middle of a lake. Codex Boturini, early 16th century, 19.8 x 25.4 centimeters, ink on amatl paper, Viceroyalty of New Spain, folio 1 (Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City)

A number of Aztec books describe the migration of the Aztec from their mythical homeland to the city of Tenochtitlan. Founded in the mid-fourteenth century, Tenochtitlan quickly grew to become an imposing imperial center.

Map of Lake Texcoco, with Tenochtitlan (at left) Valley of Mexico, c. 1519 (created by Yavidaxiu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The city of Tenochtitlan was located on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, and it featured canals, floating gardens, and bustling neighborhoods oriented around a ceremonial center. Today buried underneath Mexico City, Tenochtitlan is still present—and modern-day residents of Mexico’s capital city can see remnants of Aztec architecture and sculpture as they move about their daily lives.

View of the Templo Mayor excavations today in the center of what is now Mexico City

The Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan remains one of our best sources on Aztec political history and religious belief. Both archaeological excavations and chance discoveries have enabled a detailed understanding of the buildings and sculptures that made up the city center. Together, these works tell the story of a city that was a political capital as well as a place where the world of the gods and the world of humans intersected in powerful ways.

Templo Mayor (reconstruction), Tenochtitlan, 1375–1520 C.E.

The ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan would have been a feast for the senses, brightly colored and humming with people. On special occasions, Aztec leaders led processions, rituals, dances, and other large scale events designed to awe and impress. The Aztec empire itself was made up of many diverse peoples, some forced to assimilate. As a result, the Aztec pantheon and material culture represents cultural and religious ideas from many Mesoamerican groups.

The symbolic center of Tenochtitlan and its most important building was the Templo Mayor, translated as “old temple.” The temple was dedicated to two important deities, and was renovated and enlarged many times. It eventually stood approximately 90 feet above ground level.

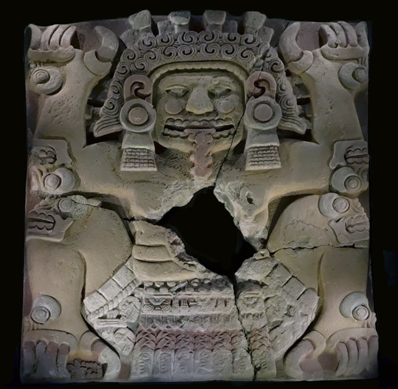

The Coyolxauhqui Stone, c. 1500, volcanic stone, found: Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Enormous sculptures in the ceremonial center, which surrounded the Templo Mayor, represented history as well as key facets of Aztec religious belief. They were also vibrant backdrops for human action, from gladiatorial fights to ceremonial processions. The following essays introduce the Templo Mayor and some of the stone sculptures erected in the area around it.

What messages about religion and history would Aztec citizens have understood from walking around the ceremonial center?

Watch videos and read essays about Tenochtitlan and the Templo Mayor

The Templo Mayor: In 1978, electrical workers in Mexico City came across a remarkable discovery—the main Mexica temple located in the sacred precinct of the former Mexica capital, known as Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

Read Now >

The Sun Stone (or The Calendar Stone): So ubiquitous that it has been used on currency, this unfinished stone records Aztec history and a future prophecy.

Read Now >

Coatlicue: This goddess has clawed feet, and wears a necklace of body parts and the snake-skirt from which she takes her name.

Read Now >

Monolith of Tlaltecuhtli: Capable of being male or female, the Earth Lord Tlaltecuhtli is shown here as a woman who has given birth.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Diverse Media

Mosaic serpent mask of Quetzalcoatl/Tlaloc, 15th–16th century C.E., Mexica/Mixtec, cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, gold, conch shell, beeswax, 18.2 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

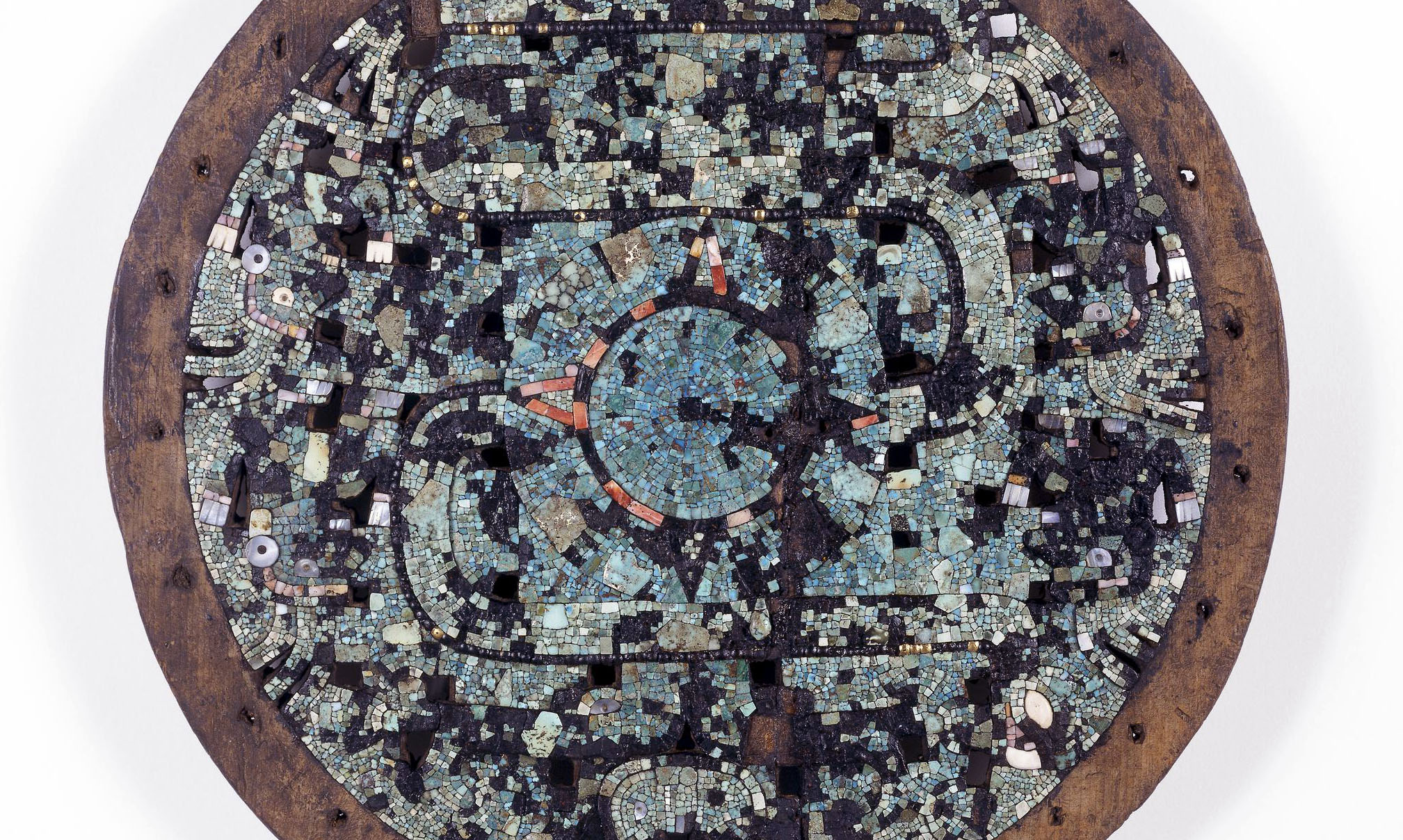

While the Aztec were known for their stone sculpture, artists in the Aztec empire and throughout Mesoamerica worked in diverse media, including ceramic, shell, wood, and paper. The dry climate of Central Mexico has enabled many works of art to survive. Paradoxically, so did the invasion of Europeans, who sent examples of Mesoamerican artistry to Europe.

Tlaloc vessel (Mexica/Aztec), c. 1440–70, found Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan, ceramic (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The works in this section illustrate the rich visual world of ancient Mesoamericans. A ceramic vessel, found in an offering in the Templo Mayor, summons the might of Tlaloc, a deity associated with rain and agriculture.

Feathered headdress, Aztec, reproduction (National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City). Original: early 16th century, quetzal, cotinga, roseate spoonbill, piaya feathers, wood, fibers, amate paper, cotton, gold, and gilded brass, Aztec, Mexico (World Museum, Vienna)

A crown made of feathers (shown below) represents the work of the amanteca, a special group of Aztec artists who worked with feathers and lived in the same neighborhood in Tenochtitlan. Wooden objects (such as the mask shown earlier) covered in intricate mosaics of shell and turquoise would have been used during ceremonial occasions among the Aztec.

Claims to hereditary nobility were based on racing ancestral lineage and proclaiming military prowess through dress and ornament. Gold pendant depicting a ruler, Mixtec, lost wax-casting, gold, 9 x 4.6 cm, from Tehuantepec, Mexico (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A gold pendant from the Mixtec region depicts a ruler in regalia that stresses his ancestral right to rule and his skill as a warrior—and was made using a “lost wax” method of casting. All of these works illustrate the rich networks of trade and communication in Mesoamerica, from the Maya blue pigment on the Tlaloc vessel, to the imported birds that provided feathers for the crown, to the metallurgical techniques first developed in South America.

Several of these artworks were transported to Europe in the early colonial period. Objects could be taken overseas because of their monetary value, but they also entered European conversations about Indigenous Americans. The Spanish Franciscan friar Bartolomé de las Casas, for instance, pointed to Indigenous artistic achievements to support his arguments against the enslavement of Indigenous populations in the aftermath of the Spanish invasions. Unfortunately, he did advocate for the continued enslavement of Africans.

While these objects tell us about Mesoamerican artistry in the Postclassic period, they are also important parts of ongoing conversations about who owns and cares for works of art. The feathered headdress (also called the Penacho de Moctezuma) now in the Ethnographic Museum in Vienna, for instance, raises vital questions about who can access Indigenous heritage after centuries of colonial exploitation.

Watch videos and read about diverse media

Feathered headdress: The Aztecs were long-distance traders, and luxury goods from distant conquered cities were sent to Tenochtitlan.

Read Now >

Tlaloc vessel: This vessel represents the goggle-eyed deity associated with rain and crops, critical for the agricultural Aztecs.

Read Now >

Turquoise mosaics: A variety of objects made by Mixtec and Aztec craftworkers were decorated with mosaic, such as masks, shields, staffs, knives, discs, and animal forms.

Read Now >

Gold pendant depicting a ruler: This Mixtec pendant represents a nobleman wearing a necklace, earrings and a lip plug from which hangs a mask with three suspended bells.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Focus on cultural repatriation

How does the feathered headdress (and other objects) relate to debates about cultural heritage and where objects in museums belong?

Feathered headdress, Aztec, reproduction (National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City). Original: early 16th century, quetzal, cotinga, roseate spoonbill, piaya feathers, wood, fibers, amate paper, cotton, gold, and gilded brass, Aztec, Mexico (World Museum, Vienna)

Despite intensifying demands to repatriate the headdress from the 1980s, [the headdress] has remained a centerpiece in the modern museum. . . .

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, “The Inbetweenness of the Vitrine: Three parerga of a feather headdress,” in The Inbetweenness of Things, ed. Paul Basu (London: Bloomsbury, 2017)

Ancestral and supernatural forces

Life-Death Figure (front and back), c. 900–1250, Huastec (found between San Vicente Tancauyalab & Tamuin, San Luis Potosi, Northern Veracruz, Mexico), sandstone with traces of pigment, 158.4 x 66 x 29.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Ancient Mesoamericans created works of art that reflected their understanding of the world around them. Imposing sculptures of deities would have populated the city center of Aztec Tenochtitlan, while in the Huastec region, artists created stone sculpture that spoke eloquently of the fine line between life and death.

Taíno artist, Zemí, c. 1000, wood and shell, from the Dominican Republic (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the Caribbean, a Taíno zemi participated in ritual practices that allowed communication between living humans and spiritual forces. Questions remain about how some of these objects acted in the world—but all of them allowed humans to access the sacred and express specific beliefs about the role of people in communicating with the gods.

How would each of these works have been used by ancient Mesoamericans, and what remains unknown about their use and meaning?

Watch videos and read an essay about ancestral and supernatural sources

Taíno Zemis and Duhos: Zemis were powerful objects that could have an impact in any aspect of Taíno life, influencing the social standing, political power, or fertility of an individual.

Read Now >

Huastec Life-Death Figure: Why is there a skeleton on the reverse of this almost life-size sculpture?

Read Now >

The House of the Eagles, and sculptures of Mictlantecuhtli and Eagle Warrior: Life-size terracotta sculptures of the god of the underworld and eagle warriors were found in the House of the Eagles, near the Templo Mayor.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Invasion

Primary source: A lament written by an Aztec chronicler describing the conquest of Tenochtitlan

Broken spears lie in the roads;

we have torn our hair in grief.

The houses are roofless now, and their walls

are red with blood.

Worms are swarming in the streets and plazas,

and the walls are spattered with gore.

The water has turned red, as if it were dyed,

and when we drink it,

it has the taste of brine.

We have pounded our hands in despair

against the adobe walls,

for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead.

The shields of warriors were its defense,

but they could not save it.

We have chewed dry twigs and salt grasses;

we have filled our mouths with dust

and bits of adobe

we have eaten lizards, rats and worms. . . .

“Broken spears lie in the road,” an Aztec lament, c. 1528. Excerpted from The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, ed. Miguel León-Portilla (Boston: Beacon Books, 1962).

The Spanish invasion of the Americas beginning in 1492 onward ignited an era of genocide, disease, and enormous cultural loss. The events of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century shaped the next five hundred years of Mesoamerican history. Despite the violence of colonization, Indigenous American cultures persevered, and millions of their descendants survive today.

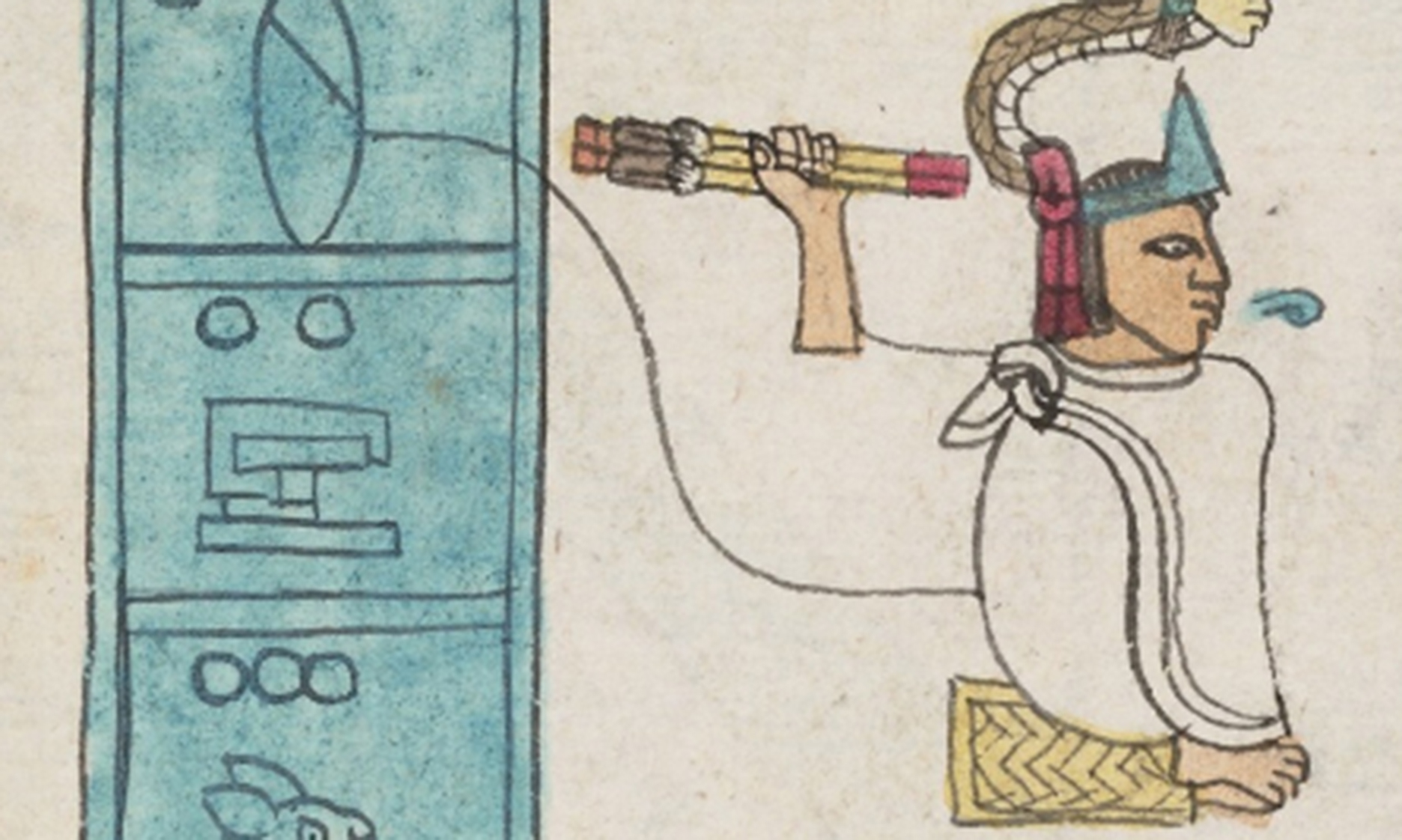

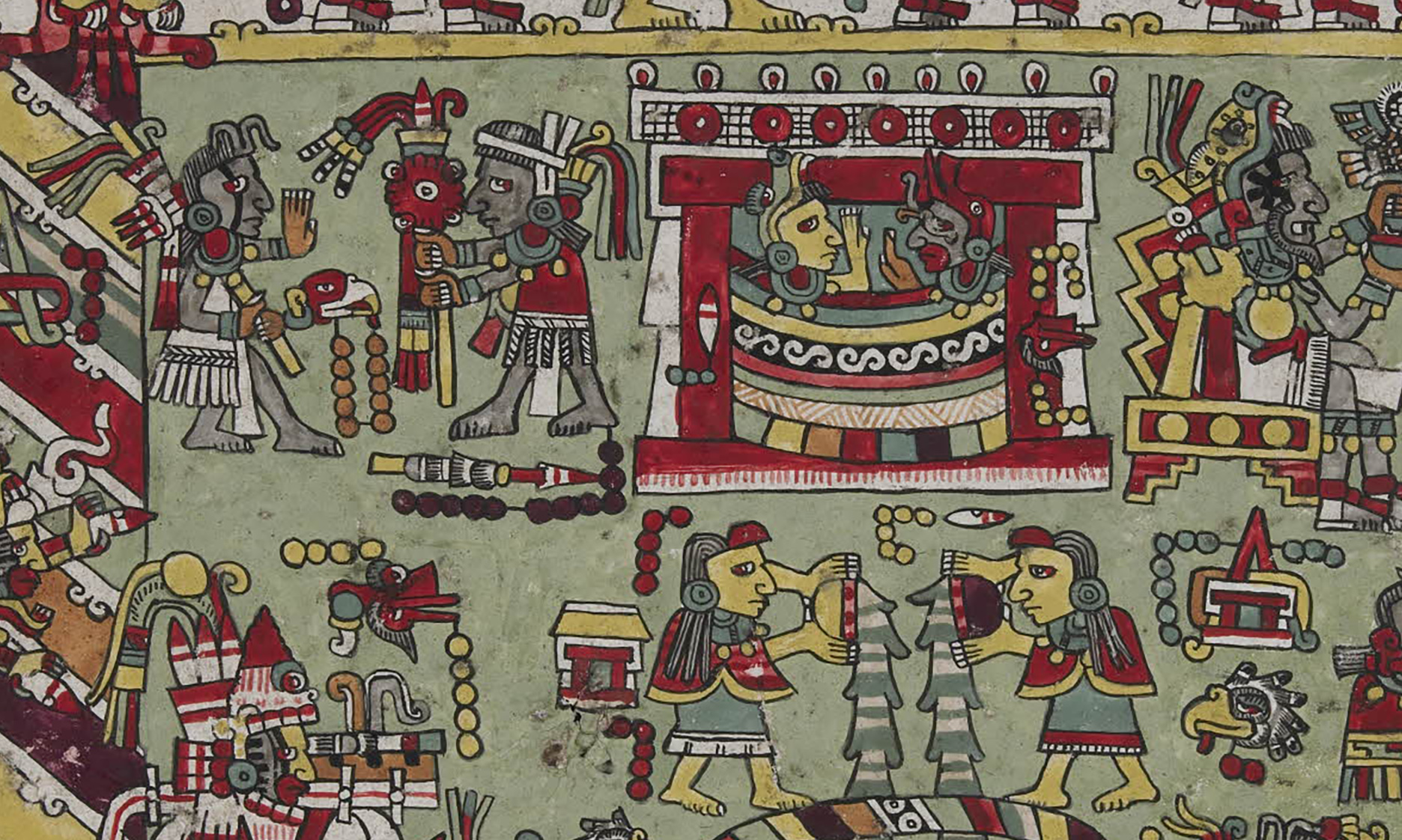

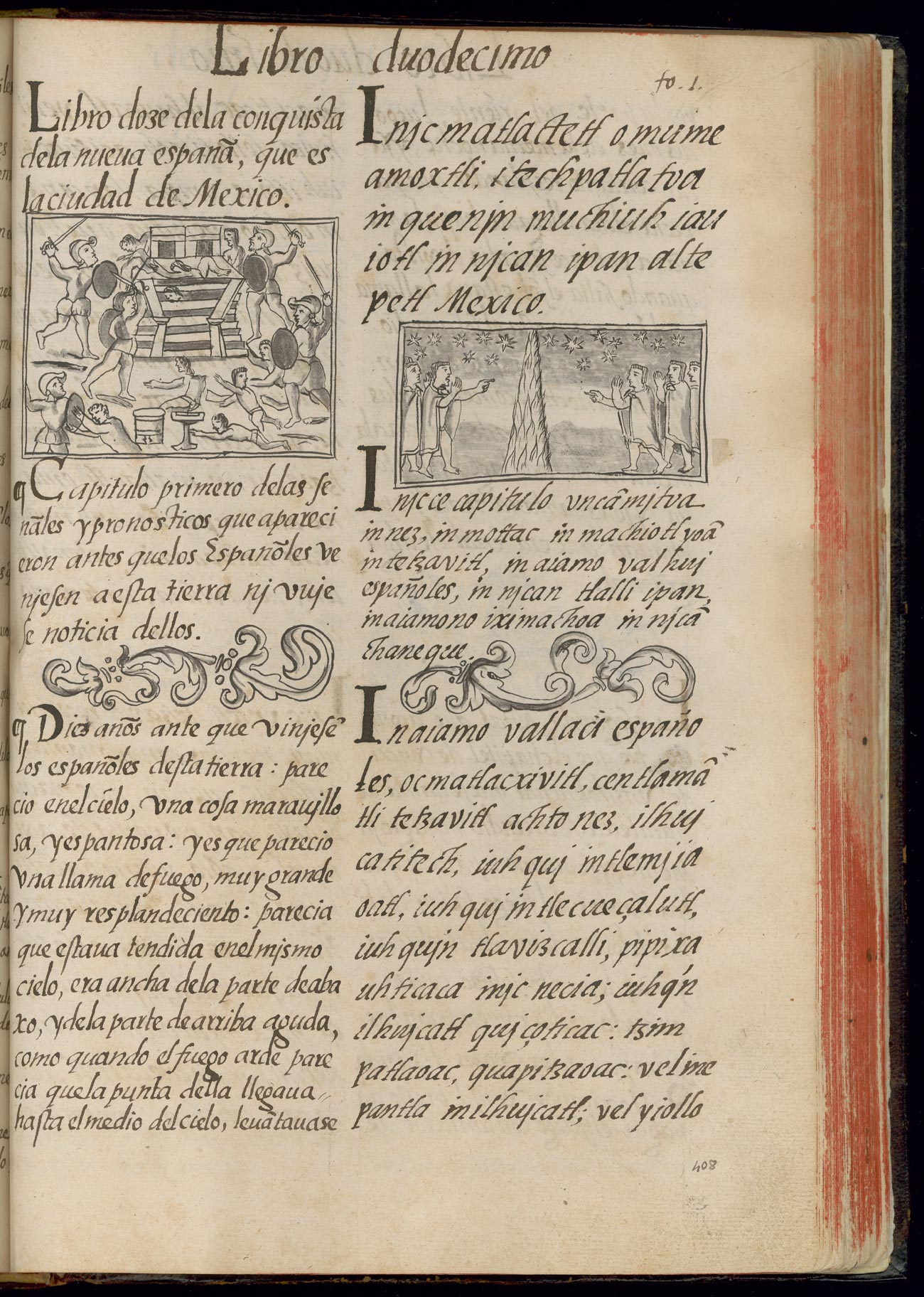

First page of Book 12 of the Florentine Codex (“Of the Conquest of New Spain”) showing the Toxcatl Massacre and a second illustration of the omens foretelling the arrival of Spaniards. The column on the left is written in Spanish, while the Column on the right is written in Nahuatl (the language of hte Nahua ethnic group, to which the Aztec belonged). Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 3, book 12, folio 1, 1575–77, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

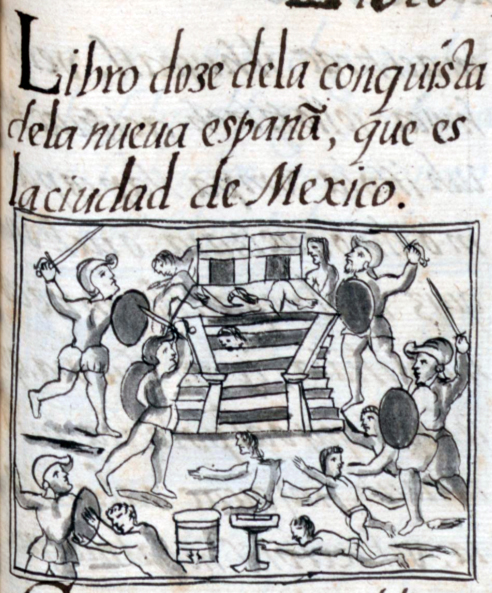

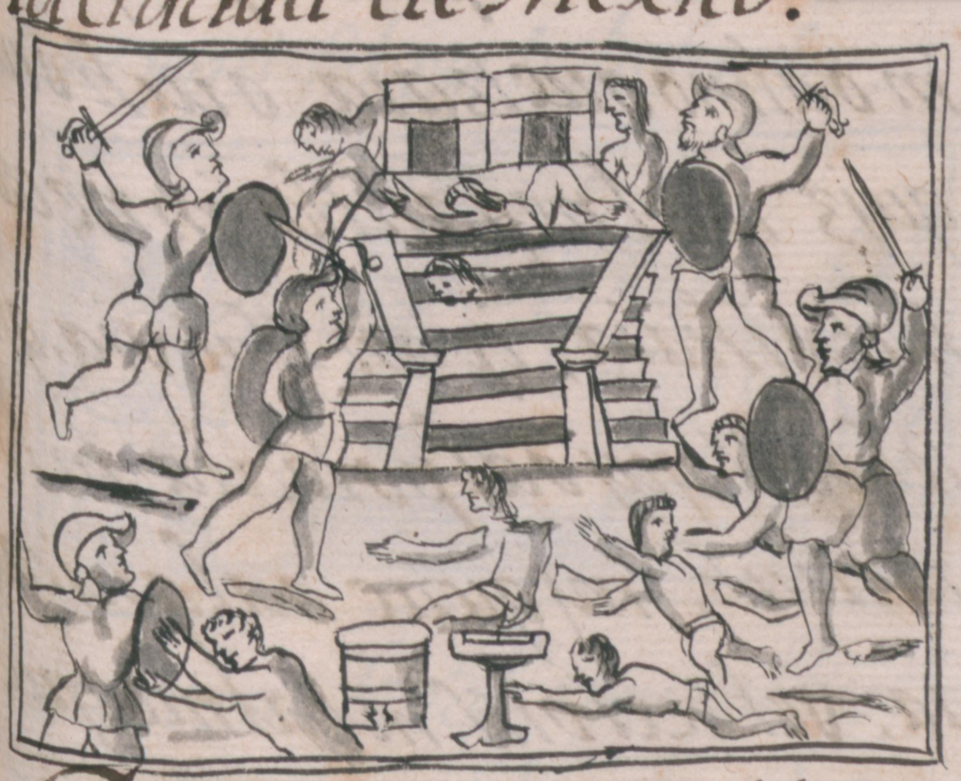

This section explores some of the immediate aftereffects of the Spanish invasion, and the vital importance of Indigenous authors and artists in recording their history. The Florentine Codex, developed by a Spanish Franciscan friar and Indigenous collaborators between 1575–77, eloquently recounts the trauma of the Toxcatl massacre that occurred on May 20, 1520. Spanish conquistadors and their Indigenous allies attacked the Aztecs during a festival, sparking the successive events that would lead to the downfall of Tenochtitlan and the Aztec Empire.

Detail of the Toxcatl Massacre in Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 3, book. 12, 1575–77, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Moreover, months after the Aztecs had expelled Spaniards and their allies from Tenochtitlan due to the Toxcatl Massacre, a smallpox pandemic interrupted the traditional celebration of ancestors during the month of Tepeilhuitl, but remnants of this ceremony survive in today’s Dia de los Muertos celebrations.

On the Caribbean islands first reached by the Spanish, the violence of invaders combined with the introduction of new pathogens had devastating effects. Still, the cultural resilience of Taíno peoples and their descendants appears in modern populations and in the rich cultural legacy of the Caribbean.

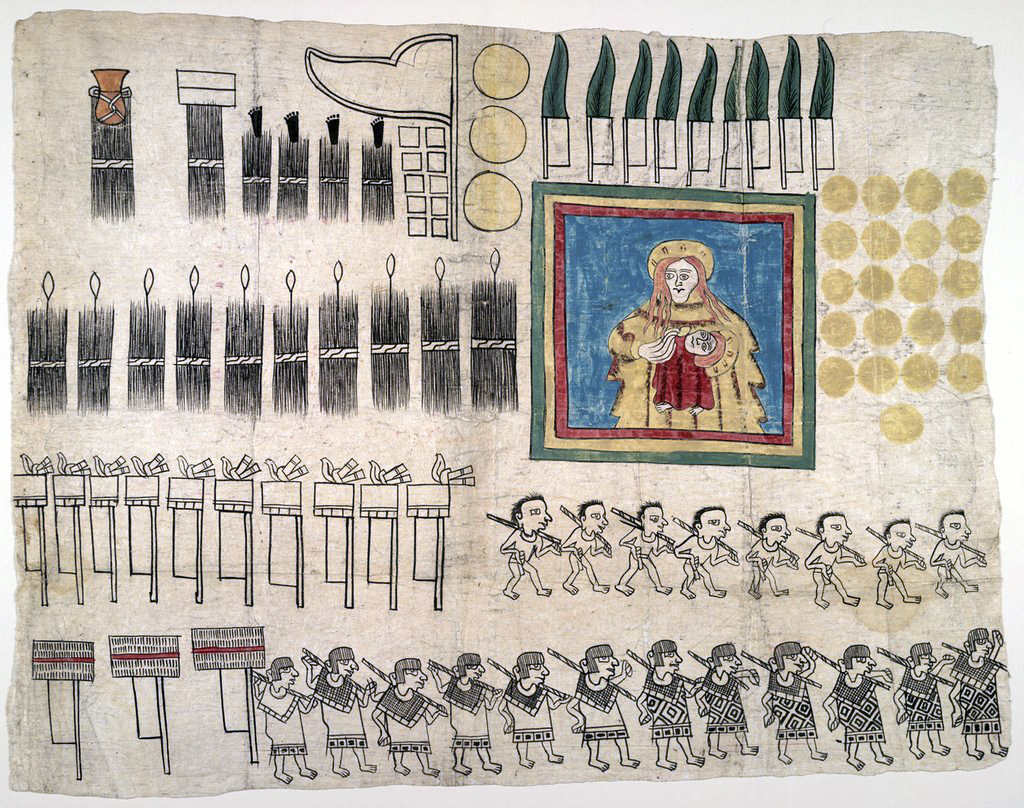

Sheet with a featherwork of the Madonna and Child, pigments on amatl paper, made by Huexotzinca artists, before 1521; then combined with written pages to form the Huexotzinco Codex, 1531, sheet 7 (Library of Congress)

Throughout the areas invaded by Europeans, surviving works of art document the resilience of people and artistic traditions in the early colonial period. In the Huexotzinco Codex, for instance, an Indigenous artist documented tribute goods paid to Spanish administrators. Works like this one tell us how Indigenous Americans both adapted and innovated within a new political, social, and economic structure.

Read essays about the invasion and its effects

Aztec art and feasts for the dead: In 1520, smallpox raged among the Mexica during the month of Tepeilhuitl when they would normally be making and eating sacred art made of dough.

Read Now >

Remembering the Toxcatl Massacre: A manuscript tells the Indigenous side of a historic battle in Aztec Tenochtitlan.

Read Now >

The Codex Huexotzinco: The images in the Codex help us to learn more about Native agency, Nahua writing systems, Indigenous knowledge, and so much more.

Read Now >/3 Completed

From books to ceramics to the Templo Mayor, the art and architecture of Mesoamerica helps us to understand the beliefs and practices of diverse ancient peoples from 900–1521. Combined, the works explored in this section speak to flourishing cultural centers with distinctive artistic programs that express ideas about politics, religion, and social structure. Although the Spanish invasion marks a sharp break with the past, none of the cultures discussed in this chapter are “lost.” Indigenous Americans continue to innovate, create, and shape new worlds.

Key questions to guide your reading

How is the art and architecture of Mesoamerica from 900–1600 similar and different to that of the Classic (200–900) period?

Where are we getting information about these cultures, and how does that affect our understanding of this art history?

How did Mesoamericans use art to express ideas about history, political power, and the divine?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow is the art and architecture of Mesoamerica from 900–1600 similar and different to that of the Classic (200–900) period?

Where are we getting information about these cultures, and how does that affect our understanding of this art history?

How did Mesoamericans use art to express ideas about history, political power, and the divine?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Amatl

Axis-mundi

Aztec (Mexica)

Aztlan

Codex

Duho

Featherwork

Hieroglyphs

Huastec

Lost-wax casting

Mesoamerica

Mosaic

Polytheism

Postclassic period

Relief Carving

Taíno

Tenochtitlan

Tonalpohualli and tonalamatl

Zemí

Learn more

Want to know more about Mesoamerica before 900 C.E.? Check out this earlier chapter that spans 200–900 C.E.