Coatlicue, c. 1500, basalt, 257 cm high, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City)

Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mother, goddess, sacrificial offering?

Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Coatlicue sculpture in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology is one of the most famous Mexica (Aztec) sculptures in existence (her name is pronounced “koh-at-lee-kway”). Standing over ten feet tall, the statue towers over onlookers as she leans toward them. With her arms bent and pulled up against her sides as if to strike, she is truly an imposing sight.

Numerous snakes appear to writhe across the sculpture’s surface. In fact, snakes form her entire skirt, as well as her belt and even her head. Coatlicue’s name literally means Snakes-Her-Skirt, so her clothing helps identify her. Her snake belt ties at the waist to keep a skull “buckle” in place. Her upper torso is exposed, and we can just make out her breasts and rolls in her abdomen. The rolls indicate she is a mother. A sizable necklace formed of hands and hearts largely obscures her breasts.

Two enormous snakes curl upwards from her neck to face one another (see the image below). Their bifurcated, or split, tongues curl downwards, and the resulting effect is that the snake heads and tongues appear to be a single, forward-facing serpent face. Snakes coming out of body parts, as we see here, was an Aztec convention for squirting blood. Coatlicue has in fact been decapitated, and her snaky head represents the blood squirting from her severed neck. Her arms are also formed of snake heads, suggesting she was dismembered there as well.

Snakes facing one another (detail), Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

You might read elsewhere that Coatlicue was decapitated by her daughter or beheaded when her son was born from her severed neck (the idea has been adopted in part to explain this monumental sculpture). However, the myth from which this story derives does not actually state that Coatlicue suffered this fate. For this reason, it is useful to review the myth—one of the most important for the Aztecs.

Battle atop Snake Mountain

The primary myth in which Coatlicue is involved recounts the birth of the Aztec patron deity, Huitzilopochtli (pronounced “wheat-zil-oh-poach-lee”). This myth was recorded in the later sixteenth century after the Spanish Conquest of 1521. The main source from which we learn about it is the General History of the Things of New Spain, also called The Florentine Codex (written 1575–77 and compiled by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, Indigenous authors and artists, and Indigenous informants). [1]

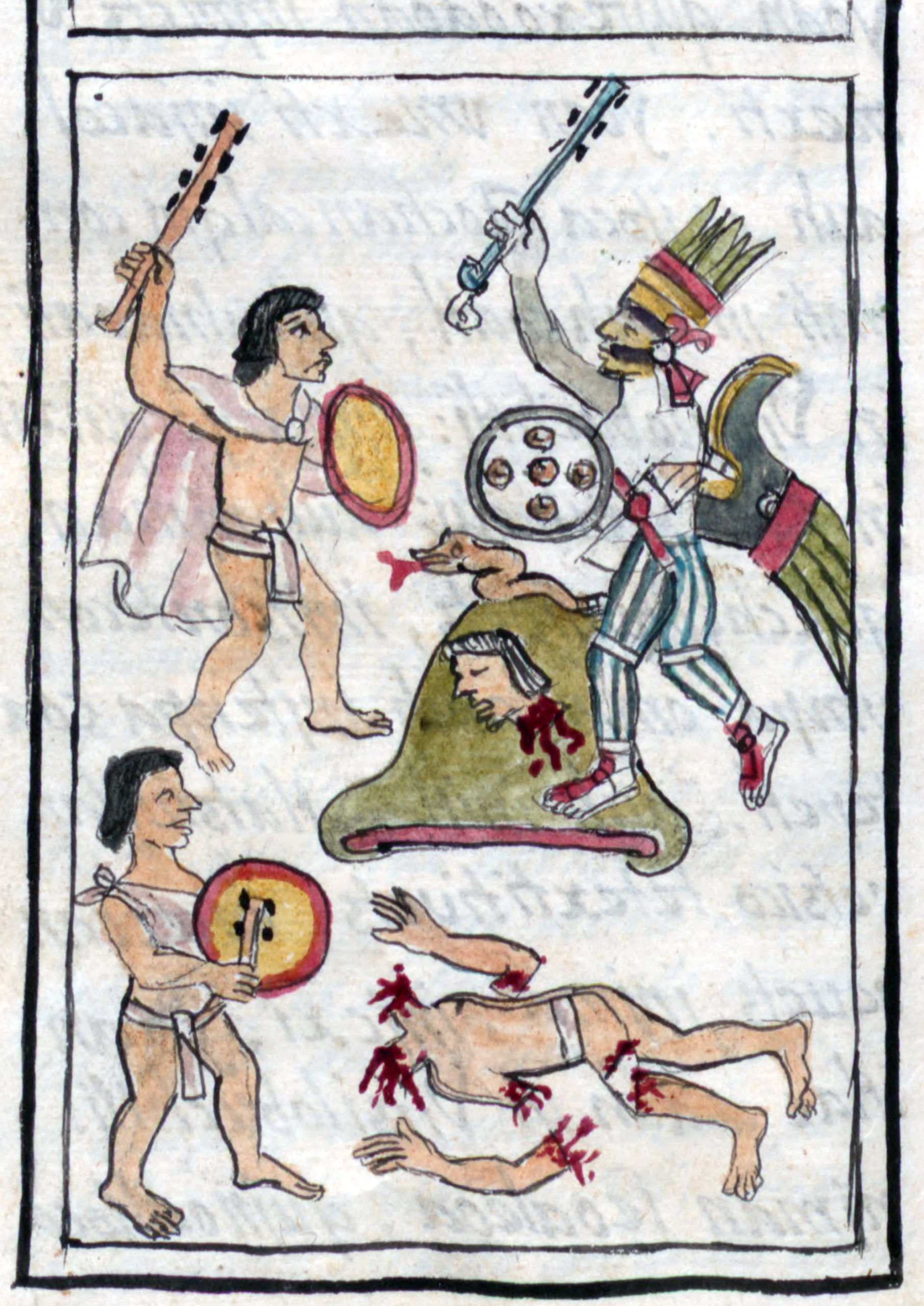

Illustration of the Battle of Coatepec from Bernardino de Sahagún, General History of the Things of New Spain (The Florentine Codex), 1575–77, volume 1, page 420 (Library of Congress, World Digital Library)

One day Coatlicue, an earth goddess, was sweeping atop Coatepec (or Snake Mountain), when a feather fell into her apron. At that moment, she immaculately conceived a son, whose name was Huitzilopochtli (a sun and warrior god). Upon hearing that her mother was pregnant, Coyolxauhqui (or Bells-Her-Cheeks, pronounced “coy-al-shauw-kee”) became enraged. She rallied her 400 brothers, the Centzonhuitznahua, to storm Snake Mountain and kill their mother.

One of the brothers decided to warn Coatlicue. Upon hearing of this impending murder, Coatlicue became understandably afraid. But Huitzilopochtli comforted her, telling her not to worry. At the moment Coyolxauhqui approached her mother, Huitzilopochtli was born, fully grown and armed. He sliced off his sister’s head, and threw her body off the mountain. As she fell, her body broke apart until it came to rest at the bottom of Snake Mountain.

But what became of Coatlicue, the mother to the victorious Huitzilopochtli and the defeated Coyolxauhqui? The myth does not mention her decapitation and dismemberment (only her daughter’s), so why would this famous sculpture display her in this manner?

Why was Coatlicue decapitated?

More recently, a new interpretation has been offered for Coatlicue’s appearance that is based on another myth (recounted in different Spanish Colonial source) concerning the beginning of 5th era, or 5th sun. The Aztecs believed that there were four earlier suns (or eras) prior to the one in which we currently live. The myth notes that several female deities (perhaps Coatlicue among them), sacrificed themselves to put the sun in motion, effectively allowing time itself to continue. They were responsible for preserving the cosmos by offering their own lives.

Skirt (detail), Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

After this point, these female deities were then symbolized by their skirts (called mantas), which could explain the careful attention paid to Coatlicue’s snaky skirt. It functions as a reminder of her name—Snakes-Her-Skirt—as well as symbolizing her as a deity and reminding the viewer of her past deeds. This might also explain why—in place of her head—we have two snakes rising from her severed neck. They represent streaming blood, which was a precious liquid connoting fertility. With her willing sacrifice, Coatlicue enabled life to continue.

Coatlicue de Cozcatlán, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), 115 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Google Arts & Culture)

Some details on the sculpture support this newer and enticing interpretation. There is a date glyph, 12 Reed, inscribed on the sculpture’s back which might relate to the beginning of a new solar era. [2] Archaeologists have also found the remains of several other monumental sculptures of female deities similar to Coatlicue, but each display different skirts. One of these sculptures stands near to Coatlicue in the Anthropology Museum, but hearts adorn her skirt instead of snakes (you can see this sculpture in the photo at the top of the essay).

Despite her fame in one of the most important Aztec myths concerning their patron god, Coatlicue did not have numerous stories recorded about her during the sixteenth century (that we know of at least). Few surviving Aztec objects display her. However, another stone sculpture in the National Museum of Anthropology—on a much smaller scale—shows Coatlicue with her head intact. We can identify her by her snaky skirt. Her face is partly skeletonized and de-fleshed. Her nose is missing, revealing the cavity. Yet she still has flesh on her lips, which are open to reveal bared teeth. Even with her head, this version of Coatlicue still seems intimidating to us today. But was she perceived as terrifying by the Aztecs or is this only a twenty-first century impression of her?

Terrifying and respected

Prior to the Spanish Conquest, Coatlicue related to other female earth deities, such as Toci (Our Grandmother). Several sixteenth-century Spanish Colonial sources mention that Coatlicue belonged to a class of deities known as tzitzimime (deities related to the stars), who were considered terrifying and dangerous. For example, outside of the 360-days that formed the agricultural calendar (called the year count or xiuhpohualli), there were five extra “nameless” days. The Aztecs believed this was an ominous time when bad things could happen. The tzitzimime, for instance, could descend to the earth’s surface and eat people or at least wreak havoc, causing instability and fear. In Spanish Colonial chronicles, the tzitzimime are depicted with skeletonized faces and monster claws—similar to what we see in Coatlicue sculptures discussed here. These sources also call the tzitzimime demons or devils.

For all their ferociousness, however, the tzitzimime also had positive associations. Ironically, this group of deities were patrons of midwives, or women responsible for helping mothers with their babies. People also invoked them for medical help and they had associations with fertility. For these reasons, they had a more ambivalent role than as simply good or bad deities, and so they were both respected and feared.

Created, buried, found, buried, found again

After the Spanish Conquest, the monumental Coatlicue sculpture was buried because it was considered an inappropriate pagan idol by Spanish Christian invaders. After languishing in obscurity for more than 200 years, it was rediscovered in 1790.

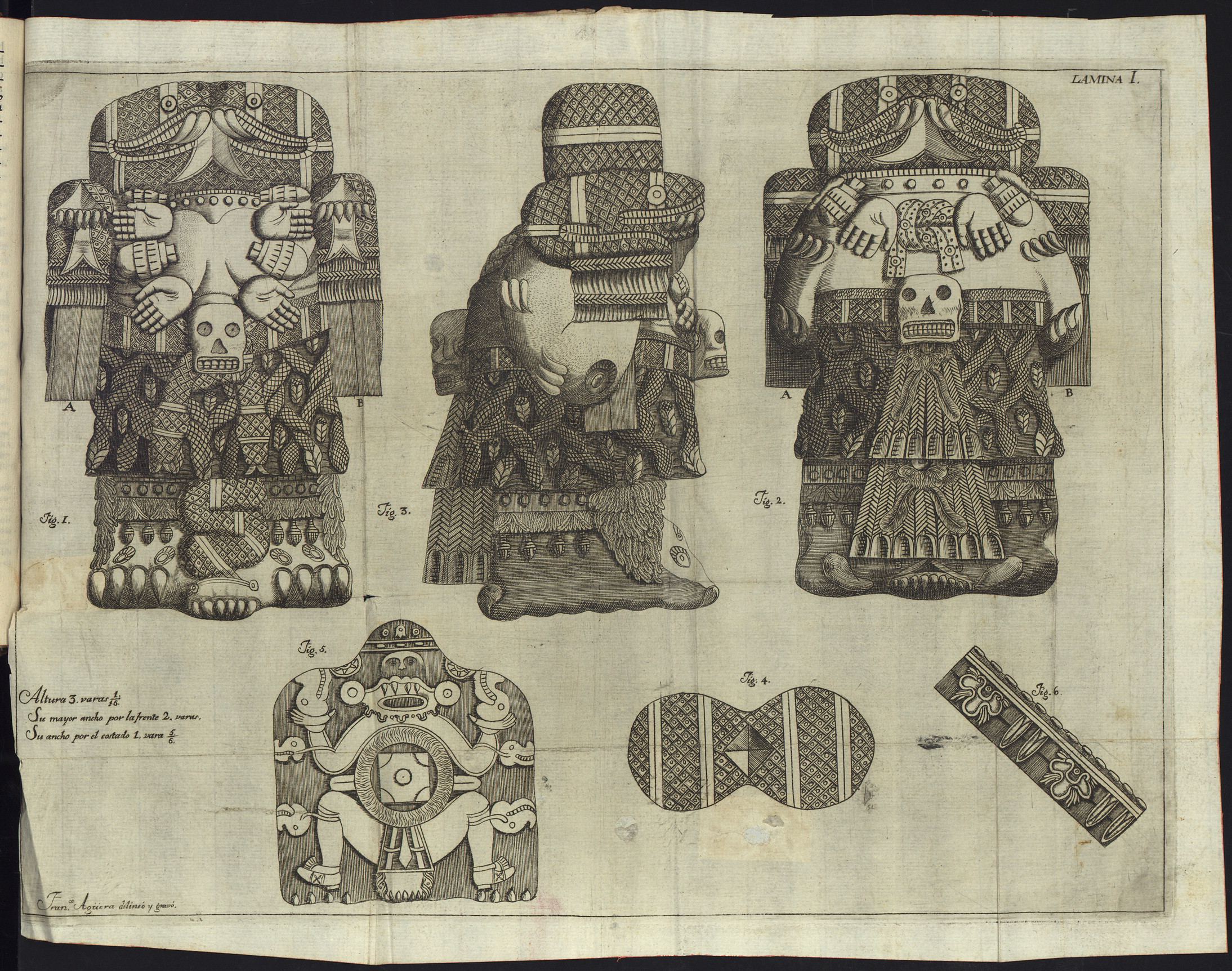

Image published in Antonio León y Gama’s 1792 book, Descripción histórica y cronológica de las dos piedras que con ocasión del nuevo empedrado que se está formando en la plaza principal de México, se hallaron en ella el año de 1790 (Library of Congress, Jay I. Kislak Collection)

Antonio León y Gama, a curious historian, astronomer, and intellectual living in Mexico City at the time, drew illustrations of the sculpture and offered his interpretation of who it displayed (he claimed it was Teoyaomiqui). Not long after it was found, however, Coatlicue was reburied—she was considered too frightening and pagan. Eventually, she was uncovered again in the twentieth century, becoming one of the crowning objects of the National Anthropology Museum and a famous representative of Aztec artistic achievements in stone sculpture.

Notes:

[1] There are several other myths that make mention of Coatlicue, but the most frequently cited myth is the one in the Florentine Codex discussed in the text.

[2] See Cecelia Klein, “A New Interpretation of the Aztec Statue Called Coatlicue, ‘Snakes-Her-Skirt’,” Ethnohistory 55, no. 2 (Spring 2008): pp. 229–250.

Additional resources

Read a Reframing Art History chapter that includes a discussion of Mexica art, “Mesoamerica, 900–16th century.”

Famsi on Aztec monumental sculpture.

Antonio León y Gama’s text in Spanish from the Kislak Collection.

Elizabeth M. Brumfiel and Gary M. Feinman, eds., The Aztec World (New York: Abrams, 2008).

H. B. Nicholson and Eloise Quiñones Keber, Art of Aztec Mexico: Treasures of Tenochtitlan (National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1983).

Esther Pasztory, Aztec Art (University of Oklahoma Press, 1983).

Richard Townsend, The Aztecs, 3 ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009).

Davíd Carrasco and Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, eds. Moctezuma’s Mexico: Visions of the Aztec World, revised (University Press of Colorado, 2003).

For myths in the Florentine Codex, see Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson, eds. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 12 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950–82).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Coatlicue,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, and we’re looking at a monumental basalt sculpture. This is just fantastic.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:14] What we’re looking at is the famous “Coatlicue.”

Dr. Zucker: [0:17] Now, Coatlicue is an Aztec goddess.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:21] She is the mother of the patron deity, Huitzilopochtli.

Dr. Zucker: [0:25] He’s one of the principal gods of the Aztec pantheon.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:27] He’s the god of war, and he’s also associated with the sun.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] Here we’re seeing a monumental sculpture of this goddess, and in fact, we think that she was one of several monumental figures of goddesses found in the sacred precinct, under what is now Mexico City.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:44] The sacred precinct was located at the very center of the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan. We refer to the sacred precinct as the “axis mundi,” this center of the world, the axis point around which the entire universe revolved, to the Aztecs.

Dr. Zucker: [0:59] This is late in Aztec culture. In just a couple of decades, the Spanish will arrive, and the Aztec Empire will be dismantled, but at this point the Aztecs ruled Mesoamerica.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:09] They ruled a vast portion of Mesoamerica, not the entirety, but a large portion of what is today, say, central Mexico. This is one of the most amazing sculptures to stand before and yet here we are, in the Anthropology Museum, and we’re standing among so many incredible finely carved basalt sculptures. What I always find so wonderful about her is that she’s leaning forward.

Dr. Zucker: [1:30] Well it makes her feel even more monumental, even more dangerous, even more present as we stand before her. So, this is a really complicated figure. Let’s start at the bottom. We do see two feet, but these feet have claws, and they have eyes.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:42] These are like monster feet. They’re zoomorphized with these talons and eyes.

Dr. Zucker: [1:47] And as we rise up, we see fur, or feathers, and patterned areas, and it’s important to remember all of this would have originally been brightly painted.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:56] And above that, the most important component of the sculpture — at least, how we identify the sculpture — is the skirt. We have all of these amazing, intertwined snakes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:05] You can see not only the snakes’ heads, but also their rattles. These are rattlesnakes, poisonous snakes, they’re intertwined in the most complex ways.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:13] Her name literally means “Snaky Skirt” or “Snakes-Her-Skirt.”

Dr. Zucker: [2:17] For instance, one of the other large female figures that we see from this precinct is known as “Hearts-Her-Skirt,” and instead of snakes, we see human hearts. That skirt is bound together by this belt, which has, both on the front and the back, a human skull.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:32] The skull is fastened together with another two snakes, and the tassels of the belt are the heads of these snakes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:39] Perhaps the most terrifying part of this sculpture is just above that, where we see a necklace made up of alternating hands and human hearts.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:47] This necklace covers her exposed torso. We can actually see her pendulous breasts, indicating that she had given birth to children, which is also referenced in the roll on her stomach. For me, I think the part that I always have found most interesting is the fact that she’s decapitated.

Dr. Zucker: [3:04] We know that because we can see these circular forms just above the clavicle.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:09] Those circles are signs of preciousness, which, in this case, is probably a reference to blood, some kind of precious liquid.

Dr. Zucker: [3:15] What we’re seeing above that is not her head, but instead two snakes that are winding out of her neck and come together face to face.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:24] This is a convention for spurting blood. What’s wonderful about this is these two snakes almost form a frontal-facing snake head. We see the tongues hanging down, the bared teeth, and this is really where Aztec sculptors, for me, are so impressive. We not only have the scales of the snakes to find, but also even the underbelly of the snakes.

Dr. Zucker: [3:45] Then there are the arms. These are a little bit hard to read. We have her forearm up so that the back of her hand is against her shoulder.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:53] It almost has this impression as if she’s about to pounce. Then we have snakes rising from her wrists, which also indicates that she was dismembered at the wrists. Then again we have, maybe, spurting blood from where her hands would have been.

Dr. Zucker: [4:04] But this is only the front of the sculpture, and the sculpture is actually carved in the round, not only on the sides, but also on the back, and even underneath.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:13] As we walk to the back, what you can also see on the arms that are pulled back are, like the feet, monster joints, these kind of zoomorphized faces with bared teeth, with the eyes, and of course, this wonderful snake skirt.

Dr. Zucker: [4:27] And a kind of bustle that shows the snakes woven together with their rattles as tassels.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:31] And another skull fastened at the belt.

Dr. Zucker: [4:34] But what I find most fascinating is that this massive piece of stone is actually carved below as well, with a shallow relief carving which we can see in reproduction.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:44] On the bottom of this sculpture we have the Earth Lord, or Tlaltecuhtli.

Dr. Zucker: [4:49] This god, the earth god, would have had this sculptural relief facing him, that is, facing down to the earth.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:56] We actually see this on a lot of Aztec sculptures, where this Earth Lord would have been touching the surface of the earth.

Dr. Zucker: [5:03] Think about the engineering that’s involved here. Moving a piece of basalt this large but then being able to upend it so that you can carve the bottom of it, and then move it into place without destroying it is a phenomenal idea.

[5:17] When the sculpture was found in 1790 in what was then New Spain, this must have been a terrifying image that was counter to everything that the Europeans and their Christianity represented.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:27] When this [was] dug up near the main temple of the Aztecs in what had formerly been the sacred precinct, it was discovered with the famous Calendar Stone, or more correctly, the Sun Stone.

[5:36] People were both fascinated and disturbed by this sculpture in particular because it was so different than anything that they had seen. They reburied it because it was considered so terrifying, whereas they took the other sculpture and placed it into the exterior of the cathedral.

Dr. Zucker: [5:51] I love that this was so terrifying that it had to be reburied, and that it was only excavated much more recently.

[5:58] So much of this iconography, so much of the imagery that’s carved onto this figure is terrifying, is aggressive to our sensibilities today. I think it’s led so many people to emphasize the issue of human sacrifice in Aztec culture.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [6:11] Human sacrifice did occur, not to the extent that early colonial Spanish sources proclaim. There are sources that claimed that 84,000 people were killed in a single day, which logistically just seems a little challenging.

[6:23] I think where we can see some of those potential references to sacrifice would be in things like the necklace of human hearts and hands.

Dr. Zucker: [6:30] Which might be a poetic metaphor. It may also be a metaphor for sacrifice itself. Now in the 21st century, to see a towering sculpture 10 feet tall, this massive stone depicting human hearts and human hands, fangs and snakes, it is a stunning image.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [6:46] I think it is a true testament to the artists of Mexica culture, Aztec culture. This particular sculpture is very well preserved.

[6:54] It shows us the interest in the natural world, say in the snakes, but combined, where you have this vision of a supernatural deity.

[7:03] [music]