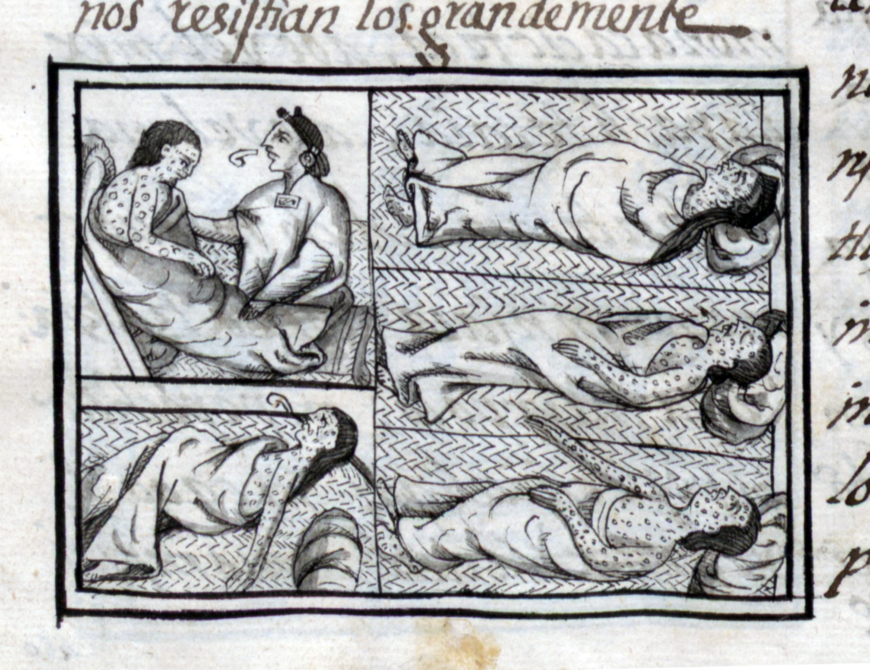

Mexica afflicted with smallpox (detail), Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, book 12, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Art and the fall of Tenochtitlan

The Mexican-Catholic tradition of Día de Muertos (“Day of the Dead”) occurs on November 1 and 2. Families begin days or weeks in advance to make treats to welcome the holiday—and now in October 2020 they still do, even as a global pandemic turns life upside down. By some horrid irony, 2020 marks the 500th anniversary of the first transatlantic pandemic—the smallpox outbreak of 1520 in the Valley of Mexico—and unbeknownst to many, the ancient roots of Día de Muertos are inextricably tied to that grim anniversary. That fall, the Mexica people (who belonged to the larger Nahua ethnic group and who were the leaders of the “Aztec” Triple Alliance) of the island city of Tenochtitlan in the Valley of Mexico should have been preparing ample amounts of amaranth dough to honor ancient traditions instead of struggling to survive disease.

Tepeilhuitl ceremony with feasting and tepictoton, Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, book. 1, folio 22, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Smallpox attacked Tenochtitlan at an important time in the Mesoamerican calendar. According to the Mexica’s account of the Spanish invasion, recorded in Book 12 of the Florentine Codex (created c. 1575–77 by a Franciscan friar and Indigenous collaborators), smallpox erupted during the sacred month of Tepeilhuitl or “The Festival of the Mountains”—one of the oldest religious festivals associated with the Mexica and their capital at Tenochtitlan. Normally the Mexica observed that holiday, one of their twenty-day months, by remembering their dead relatives through communal feasting, song, and dance.

The sacred festivities date back to to the foundation of the city Tenochtitlan in the 14th century, when, according to colonial-era manuscripts, as the Mexica slogged through marshy lands of the Valley of Mexico in search of their new home, and arrived at a place called Iztacalco. There they performed the amatepetl or “paper-mountain” ceremony in the year 13 Rabbit (likely 1362 C.E.). One Nahuatl (the language of the Nahua) text describes the solemn ceremony as one where “people made many hills of dough and gave them eyes and mouths of seeds.” [1]

During the month of Tepeilhuitl in 1520, however, smallpox raged among the Mexica for sixty days, the disease then spread throughout the countryside. Only months before, the people of Tenochtitlan had cast out the Spaniards (led by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés) for committing a massacre during another festival known as Toxcatl. The Mexica had crafted a life-sized dough image of their patron deity Huitzilopochtli, and when they began to dance and sing before it, Spanish onlookers used that act as a rationale to attack the surprised and unprepared worshippers. As the fall set in, the Spaniards returned and were prepared to choke off the city with a months-long siege. By that time, its citizens had borne witness to the horrors of smallpox, many unable to move under the pain of erupting pustules that blanketed their skin. Basic functions in Tepeilhuiltl had been disrupted by the crippling disease as “starvation reigned, and no one took care of others any longer.” [2] Instead of creating edible art and honoring the ancestors, the Mexica faced famine.

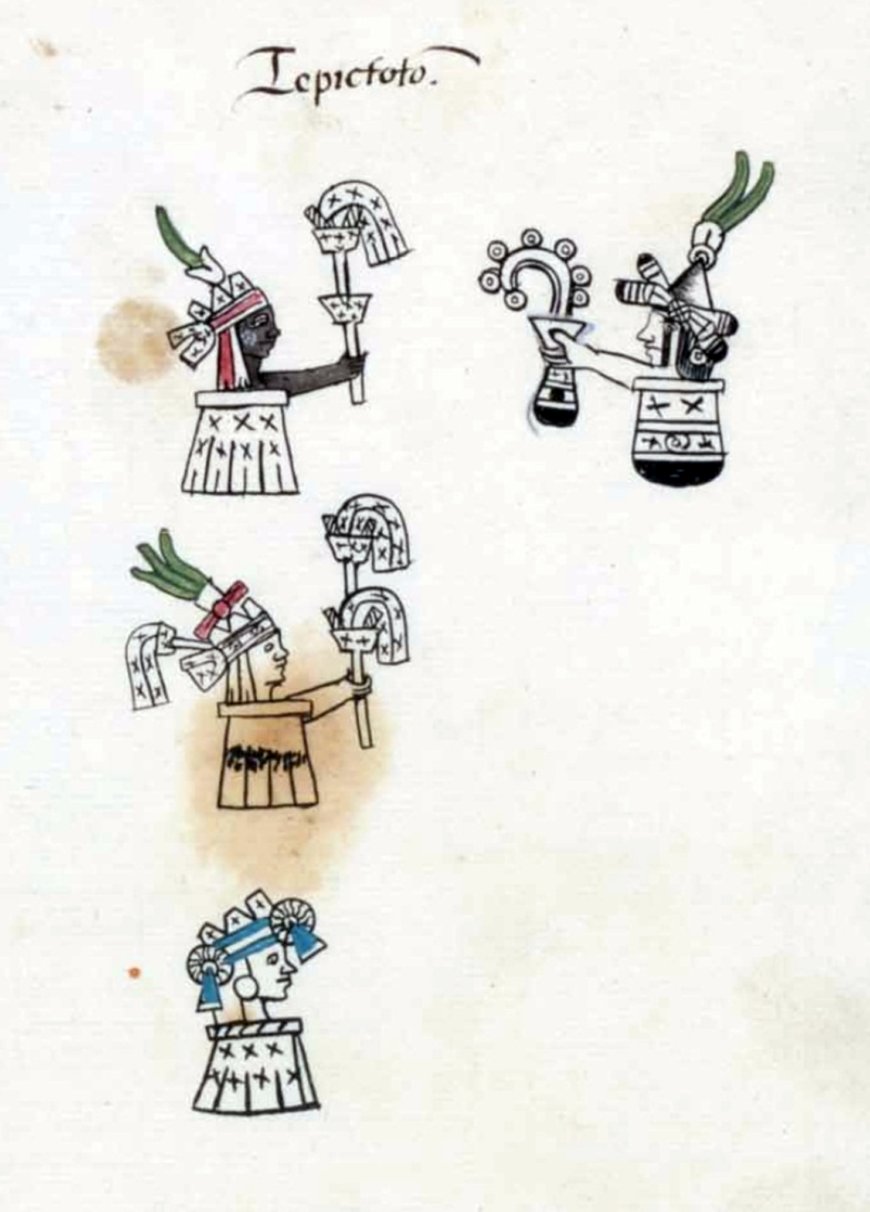

Illustration of tepictoton, Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, Codices matritenses (Primeros Memoriales), 1558–85 (Royal Library, Madrid)

Crafting Edible Mountain-Gods

Amaranth grain (photo: Gaurav Dhwaj Khadka, CC BY 4.0)

The month of Tepeilhuitl was dedicated to honoring the natural and supernatural environment while also commemorating the recently deceased members of a community. It knitted communities together with its public displays of religious artwork, musical and dance performances, and acts of gifting food and drink to supernatural forces. A central aspect was the act of crafting, displaying, and eating handmade sacred art made of dough.

These works of sacred art were known as tepictoton, or “small molded ones.” They were sacred objects consisting of three basic components: an inner portion containing a collection of amaranth-dough figures that were the likenesses of actual living or dead people; an exterior shell that looked mountain-like and encased the dough figures; and a final layer of paint, appliques, and ornamentation that associated the mountain with a particular deity. Nahuas used the tepictoton as a type of altar or shrine in the process of commemorating their dead.

Popocatépetl in 2017 (photo: SchneidIt, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Nahua cosmology, mountains were concretions around water, and life-sustaining rain clouds formed above them. Famed mountains in the Valley of Mexico included Mount Tlaloc, Popocatepetl, and Iztactepetl. Interviewing Nahuas in the 1550s, the priest Bernardino de Sahagún recorded that

“Everyone fashioned them in their homes… at midnight, and after they had been fashioned, they made an offering of incense to them. They also sang to them… a song to each of the mountains… Payment [to the gods] was made. They decapitated birds in their honor then they made offerings of tamales to them.” [3]

With everyone honoring their local mountain-gods, the displays clearly reflected an important religious tradition.

Dough objects, as is their nature, tend to be perishable, and we lack extant examples of these ancient mountain-gods to learn from today; we must rely on colonial-era texts and images (those created after the defeat of the Mexica in 1521). Some of the best sources for studying tepictoton include both Sahagún’s Primeros Memoriales and the Florentine Codex that followed, as well as other descriptions made when Indigenous elders were interviewed by non-Indigenous men or Nahua assistants.

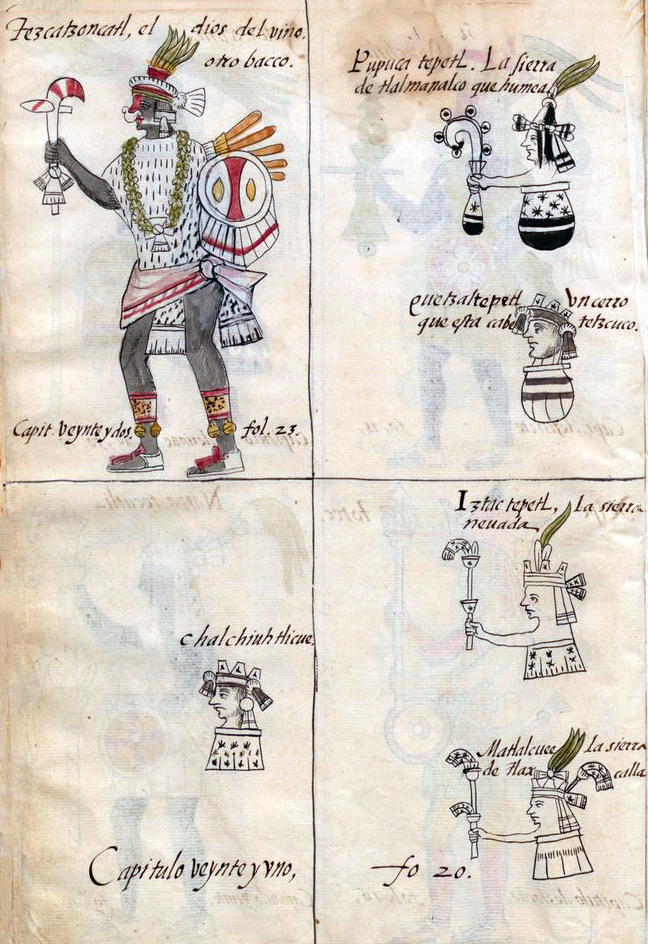

Deity (upper left) and tepictoton, Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, book. 1, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Images can help to identify patterns in the rituals of the month of Tepeilhuitl. An image in the Primeros Memoriales and reproduced in Book I of the Florentine Codex illustrates five mountain-gods (the tepictoton) whose bodies consist of an upper, human-like head and a lower base made to look like a bulbous vessel or a fanned skirt. Three of them have a single arm extending into the air before them that clutch small replicas of “their stout reed staves, their lightning sticks, their cloud-bundles.” [4]

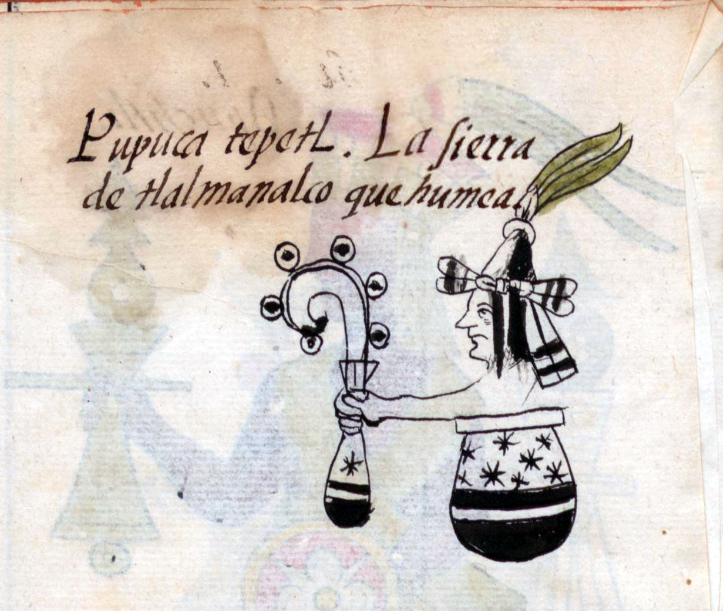

Popocatepetl (detail), Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, book. 1, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

The artist renders fine details, including splatter marks of rubber paint that were applied to the skirts and sashes worn by the mountain-gods. Identifiable features distinguish each one. For instance, the likeness of the mountain Popocatepetl dons a black and white peaked cap and bears a vessel that fumes a curly stream of smoke. It represents the sacred forces of the active volcano located to the southeast of Tenochtitlan. According to the text, the tepictoton were then “placed on the ground, the one following the other in a row, and they were facing the fifth [figure]” [5].

The main ingredient

The mountain-god creations consisted primarily of nourishing amaranth seed dough, called tzoalli (tzohualli in Huastecan Nahuatl). The dough was a chief ingredient in worship, and the people of Mexico have enjoyed it in various forms, from dried cakes to soupy atoles, for millennia. Dough figures looked uncomfortably human as they were given “teeth of gourd seeds… eyes of fat black beans.” [6]

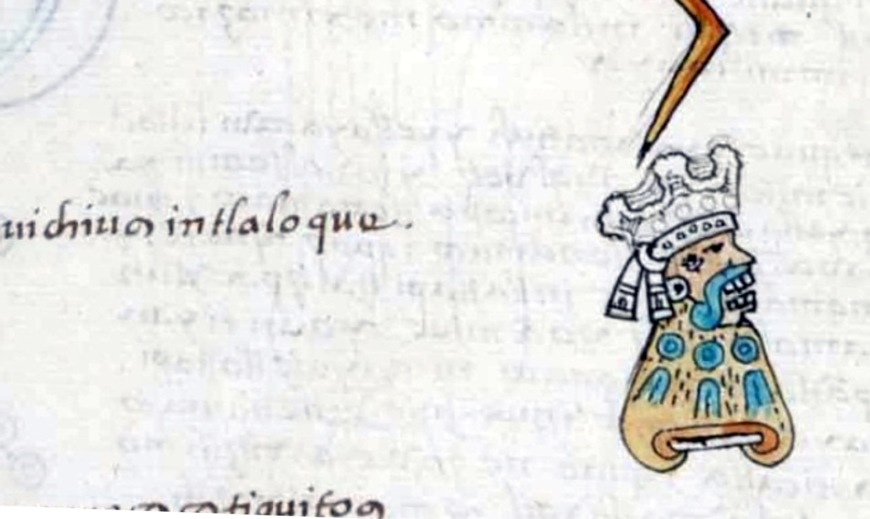

Tlaloque (detail), Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, Codices matritenses (Primeros Memoriales), 1558–85, (Royal Library, Madrid)

Another depiction from the Primeros Memoriales shows the exterior of a tepictoton (mountain-god) in the likeness of Tlaloc (it is a tlaloque, a little helper of Tlaloc). Its head and body are honey-yellow (amaranth seeds, huauhtli, had an amber quality and looked like pale fish roe) and the tiny black strokes give the appearance of black seeds dimpling the mountainside. Tlaloc has three blue rain and water symbols painted on his side, and he wears a white cotton crown (its fluffy edges apparent on the codex page), a headband, and an earspool. His face consists of exposed teeth made from gourd seeds, and the classic blue-green “Tlaloc mouth”—a mustache-like symbol framing the upper lip, its ends curling back and upward.

Tepeilhuitl is directly related to the god Tlaloc, who was a water deity overseeing rain and lighting. Tlaloc was responsible for Nahuas drowning or struck down suddenly, and he manifested in human bodies by crippling them with palsy or stiffening their limbs. Those figures that made up the inside of each tepictoton were specifically the likenesses of those living or dead people affected by Tlaloc’s powers.

The dead inside

Before the exterior of a mountain-god display could be fashioned, Nahua artisans first crafted little dough figures called “children,” which represented the dead and afflicted. First, they would craft “skeletons” (in Nahuatl imomoio, “their bones”) for individual figures. This was done with sticks of wood or compacted bars of amaranth dough to provide a frame. Around the figure’s “skeleton,” they applied more dough to make the body, and these along with other dough figures in the shape of “serpents” (known as ehecatotontin or “little winds” in Nahuatl) would be piled together in the participant’s household courtyard. The children and little winds were then curated into piles by the artists, one pile for each mountain-god to adorn the courtyard that year.

Tepictoton (detail), Bernardino de Sahagún and Indigenous collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, book. 1, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Over these they pasted more amaranth, which they pressed to form the geologic and human-like features of the tepictoton. As they finished the exterior with paint, feathers, and seeds, they also wrapped the mounds of dough with a paper skirt, a final layer of dress to cover both the mountain and its dough children inside.

At the end of the month of Tepeilhuitl, observants cracked open the mountain-god dioramas, pulled out “children” and “little winds” from the interior, carried the figures to a sacred shrine called the Mist House, and carefully washed and prepared them for consumption. Eating replicas of their dead—the little dough bodies now metaphorically charged with twenty days’ worth of adoration and memories—Nahuas believed they were nourished with the same powers as the dough bodies.

During the month of Tepeilhuitl in 1520, the Mexica starved through a pandemic when they would normally be feasting to remember their loved ones and looking forward to a prosperous future. We do not know how, if at all, the Mexica celebrated that year.

Ofrenda for Dia de los Muertos, 2012, Castillo de Chapultepec, Mexico City, Mexico (photo: Juan, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Edible arts in times of sickness

Adopted and adapted up to the present, every fall we are reminded of Tepeilhuitl’s cultural resilience in each ofrenda (family altars) that families make for Día de Muertos. Artisanal foods grace family altars and tombstones in the cemetery, and everyone enjoys eating sweet breads, called pan de muertos, decorated with crossbones designs, and glittering white calavera sugar skulls. People do not make tepictoton nor tzohualli figures for eating these days, but alegrías (tasty biscuits made of toasted and honey-coated amaranth seeds) reflect some of the deeper roots of honoring the sacred landscape. Celebrating the tradition of Día de Muertos will need to be different this year (2020) due to disease, with many festivals across the globe cancelled to limit the spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, many of this year’s ofrendas will memorialize the lives we have lost to the virus. Hopefully, families can still honor their roots in a safe and tasty way.

Notes:

[1] Codex Aubin, Am 2006 Drg.31219, Folio 23v © The Trustees of the British Museum and Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, Crónica mexicáyotl, Adrián León (trans.), third edition (México Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas 1998)

[2] James Lockhart (ed. and trans.), We people here: Nahuatl accounts of the conquest of Mexico, Vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993: pp. 180-183).

[3] Bernardino de Sahagún, Primeros memoriales (trans. by Thelma D. Sullivan and Henry B. Nicholson, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2017: p. 64).

[4] Bernardino de Sahagún, Primeros memoriales, p. 114.

[5] Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 1: The Gods (trans. by Arthur JO Anderson and Charles E. Dibble; Santa Fe: The School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1970: p. 49).

[6] Florentine Codex, book 1, p. 47.

[7] Florentine Codex, book 1, p. 75.

Additional resources

Look at the Florentine Codex

Carolina A. Miranda, “How a vital record of Mexican indigenous life was created under quarantine,” LA Times 2019

For those interested in learning more about Día de Muertos and ofrendas, please do so in a respectful and genuine manner

Learn more about Día de Muertos from National Geographic

Celebrate Día de Muertos by honoring Mexico’s ancient roots and shape your homemade sweets from indigenous ingredients

Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain, 13 Vols. (edited and translated by Arthur J O Anderson and Charles E Dibble; Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research; Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah, 1950-1982).

Michel Graulich, Myths of ancient Mexico (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997).

Frances E. Karttunen, An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992).

Elizabeth Morán, Sacred Consumption: Food and Ritual in Aztec Art and Culture (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2016).

John F. Schwaller, The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019).