Mosaic serpent mask of Quetzalcoatl/Tlaloc, 15th–16th century C.E., Mexica/Mixtec, cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, gold, conch shell, beeswax, 18.2 x 16.5 x 12.5 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Mexican turquoise mosaics

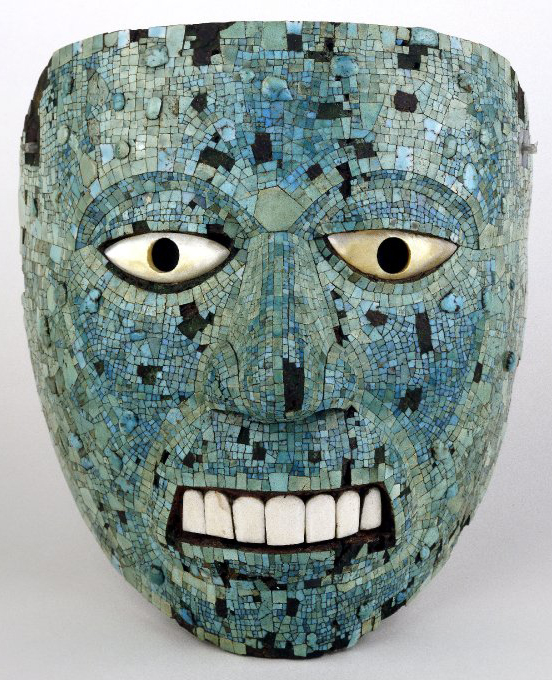

Turquoise mosaic mask (human face), 1400–1521 C.E., cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, mother-of-pearl, conch shell, 16.5 x 15.2 cm, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

Ancient Mexico is renowned for the production of vivid greenstone mosaics. Early Zapotec and Maya examples from the Classic period were made predominately of jade. Later, turquoise became the material of choice. The finest examples of turquoise mosaics date to the Late Post-Classic period and were probably fashioned by highly skilled Mixtec craftsmen who excelled both in stone and metal work.

A variety of objects were decorated with mosaic, such as masks, shields, staffs, knives, discs, and animal forms. These objects, as well as raw chunks of turquoise, were sent to Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, as tribute and used to adorn images of the gods, as well as priests and the nobility. [1]

Mosaic skull of Tezcatlipoca, c. 15th-16th century C.E., Mixtec/Mexica, turquoise, pyrite, pine, lignite, human bone, deer skin, conch shell, agave, 19 x 13.9 x 12.2, Mexico © Trustees of the British Museum

The mosaic work on these objects usually overlies carved wood, although a number of human skulls decorated in this way are also known. Although the mosaics are usually described as ‘turquoise’ they in fact incorporate a diversity of materials. Various types of shell and many minerals were used in the mosaic work and to fashion inlays. Some elements were gilded and the mosaic was held in place using plant resins (usually pine resin).

Around 25 mosaics are known in Europe and most of these are thought to date to the time immediately before the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521. Mosaics are listed in the early colonial inventories of objects that were sent to Europe at this time, although the descriptions are not sufficiently detailed to identify the exact object to which they refer. More mosaics are preserved in collections in Mexico and the United States, including recently excavated and reconstructed examples of discs or shields from the Toltec capital, Tula and from offering caches made at the Templo Mayor in the heart of what is now Mexico City. There are nine Mexican mosaics are in the collection of the British Museum.

Wooden ceremonial shield with mosaic inlay, Mexica/Mixtec, 15th-16th century, from Mexico, 31.6 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

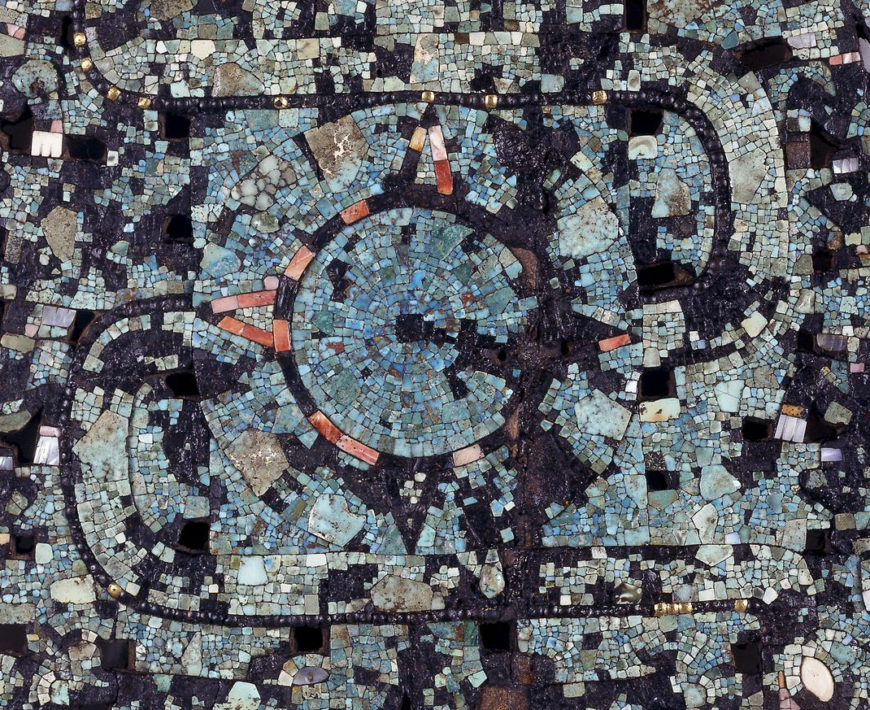

An intricate mosaic which illustrates the Mexica universe

This mosaic covered wooden disc was probably once the central element of a striking ceremonial shield. Among the many ceremonial shields listed in inventories of shipments sent to Spain by Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) 25 were decorated with turquoise mosaic. A companion of Cortés, the ’anonymous conqueror’, observed that mosaic shields were ‘not of the kind borne in war but only those used in the festivals and dances which they are accustomed to have’.

Wooden ceremonial shield with mosaic inlay, Mexica/Mixtec, 15th-16th century, from Mexico, 31.6 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Wooden ceremonial shield with mosaic inlay, Mexica/Mixtec, 15th-16th century, from Mexico, 31.6 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The mosaic on this shield is worked in turquoise and shell from Strombus (conch), Spondylus (thorny oyster) and Pinctada (mother-of pearl). ‘Beads’ of pine resin covered with gold leaf are also used in the design which portrays the principal divisions of the Mexica universe. At the centre is a solar disc, picked out in bright red Spondylus shell. The four rays emanating from the solar disc divide the earth into four quarters. In each quarter stands a figure with raised arms, these are skybearers, gods whose role was to support the sky. The shield also displays a vertical design in the form of a serpent which emerges from toothed jaws and coils around a tree. The tree represents a ‘world axis’ connecting the underworld, earthly and celestial realms.

Pine was a source both of the resin adhesive used on this shield and the wood from which it was carved. The surface of the wood was carved to delineate the design by giving relief prominence to certain elements such as the serpent and the skybearers. Numerous perforations in the shield further emphasize the outlines of the skybearers.

Around the edge of the shield the wood is not decorated but is pierced by a series of fairly regularly spaced holes. These may have been used to attach feathers. According to sixteenth-century descriptions, colored feathers were used to decorate the edges of mosaic shields.

© Trustees of the British Museum