Historical periods are the sign posts we use to navigate the stream of Mesoamerican history. Historians and archeologists have defined these periods, such as Archaic and Classic, based on the changing characteristics of the material culture of this region. This essay provides a broad overview of the different periods of Mesoamerican history.

It is important to note though that historical periods are not real. No one, as far as we can tell, in ancient Mesoamerica, ever woke up and said, “This is 150 C.E. I must be now in the Classic period with a different set of characteristics.” Periods are a way for historians looking back on human growth and development to structure and assess these time periods in ways that help us think about them. In that sense, they’re not real to the history itself nor to the people who lived through that history. They’re what we call heuristic devices. They simply help us to organize this great stream of time that is Mesoamerican history.

You will notice that essays across Smarthistory might use slightly different date ranges for periods—this is because not everyone agrees on the exact boundaries of each period.

Archaic period, c. 14,000–1800 B.C.E.

We begin this story with the entry of humans into the Americas. People did begin to modify materials into objects similar to what we might now call art, such as an Archaic camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine, but generally throughout this entire period, we have found very few such items. Instead, during this historical period, we can talk about the foundations of Mesoamerican civilization. We can start with a simple but critical question: How did the people of this early period feed themselves? Throughout the Archaic period, hunting and gathering is the main mode of survival. They were hunters of megafauna—very large animals, many of which became extinct during this period (the mastodon for one). They also gathered plants to supplement their diet, though they did not grow these plants. When people consciously undertake agricultural activity, that is another type of lifestyle entirely, and something that we do not get with the early hunters in the Archaic period.

Pre-classic period, c. 1800 B.C.E.–150 C.E.

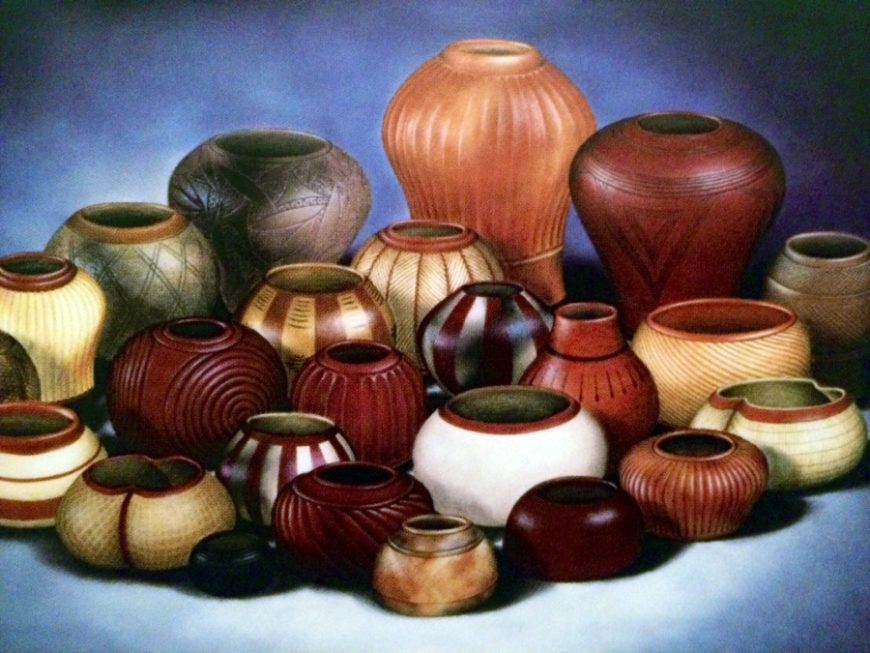

The next period is called the Pre-classic. It opens with the widespread adoption of ceramics. Bowls, jars, and figurines were made from a widely available material—clay—that could be shaped into storage vessels as well as expressive clay sculpture. It only takes fire to transform the wet clay into a permanent form. Ceramics develop alongside a revolutionary new technique for producing food: farming.

It is during the Pre-classic period that the the slow domestication of corn or maize (maíz in Spanish), which is so important to Mesoamerican culture, takes place. Corn begins to be planted regularly and becomes an important part of the diet. Beans and squash also become important staples alongside corn. All these need to be stored and cooked, and ceramic vessels filled this need. Some of the earliest decorated ceramic containers seem to have been used for making corn beer, an important source of safe hydration and an important feature of the ceremonies held in these first farming villages.

Tlatilco figurine of a woman with a dog, Tlatilco, c. 1200–600 B.C.E., ceramic (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The rise of agriculture is an important foundation for the Pre-classic period, but it is not the only issue that we talk about when we discuss the Pre-classic. This period also saw the rise of urban civilization. People begin to live in cities early on in this period, fully adopting agriculture and settling down; this is often described in relation to the Neolithic revolution. They are no longer hunting and gathering and moving around as their main dietary or food strategy. While people did still hunt and go out and gather food, it was not the main way that they fed themselves.

Double-faced female figurine, early formative period, Tlatilco, c. 1200–900 B.C.E., ceramic with traces of pigment, 9.5 cm. high (Princeton University Art Museum)

The rise of villages and towns occurs when people settle together to work their fields, and they develop particular cultural practices as they gather together. One example is Tlatilco, which was located close to a lake, where fishing and bird hunting became important ways to obtain food. Burials at Tlatilco included hundreds of ceramic figurines shaped like humans and animals.

Soon after the establishment of villages, more complex organizations and settlements arise, we call these cities. The difference between a village and a city is that people in cities develop specialties and hierarchies. Not everyone grows the food. This is no longer a settlement of farmers. A city is a settlement of many different paths, offices, and jobs—all working together in a complex system.

With the rise of cities comes the rise of hierarchies. This period shows the clear evidence of elites, or people at the top of the social pyramid. Elites in Mesoamerica patronize or pay for particular kinds of art to be associated with their high status. For instance, they get involved in the trade and the working of precious materials like jade; this is a really important part of Pre-classic artistic development because artists were given the time and resources to develop their skills, under the patronage of these new elites.

Finally, in the middle of these cities we get monumental art and architecture. An example of major Pre-classic sites are the Olmec cities of San Lorenzo and La Venta. San Lorenzo flourished between c. 1200–900 B.C.E. and had a wealth of sculpture set into tableaux (interacting sculptural figures) in the center of the city. Archaeologists discovered a palace at San Lorenzo with an attached sculpture workshop, making clear the relationship between the elite and the emerging class of artists. The city of La Venta flourished between 900–400 B.C.E. and had a massive pyramid and large stelae (an upright flat slab of stone worked in relief on one, two, or four faces). Both Olmec cities of San Lorenzo and La Venta exhibited colossal heads of rulers, and smaller objects made in precious materials like jadeite.

Pyramid of the Moon seen from the Avenue of the Dead with Cerro Gordo in the distance, Teotihuacan, Mexico

Classic period, c. 150–650 C.E.

The Classic period is easier to define because it’s really an elaboration of the Pre-classic patterns. Monumental art and architecture in cities gets more elaborate and there are more traditions because there are more cities.

The Classic period is defined by the rise of the megacity in historical writing that treats the Classic period, especially the single great metropolis called Teotihuacan. Teotihuacan was the sixth largest city in the world in its heyday around 400 or 450 C.E. It was a city on a grander scale than any other cities in Mesoamerica by this time, and it had a profound influence on other cities and places during the Classic period.

In the Maya region (southern Mexico and Central America) we also find powerful and prosperous cities, including Palenque, Yaxchilán, and Tikal. Rulers of these city-states commissioned buildings and monumental sculptures to communicate messages of power and divinity, including portrait stelae.

Epiclassic, c. 650–950 C.E.

The single most defining characteristic of the Epiclassic period is the lack of Teotihuacan to serve as the central force in Mesoamerican civilization. By 650 C.E., when the Epiclassic begins, Teotihuacan was a shadow of its former self, with a much smaller population and little real influence outside the valley of Teotihuacan.

El Tajín Ball Court, c. 800–1200 C.E., Classic Veracruz Culture (photo: Oscar Zorrilla Alonso, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The political history of the Epiclassic is the story of the power vacuum left by Teotihuacan’s demise. In many areas, that vacuum was filled by local powers, with individuals who had newfound access to wealth that was used to create monumental architecture and elite art. The Epiclassic is the story of these secondary or regional power centers, that grew up in the wake of Teotihuacan’s fall. It is the story of sites like Xochicalco, Cacaxtla, and El Tajín. This period is marked not only by the rise of these regional centers, but also by interesting, accomplished, eclectic art styles, and a plethora of elite architecture.

In terms of art history and architectural history, it’s a vibrant period. The decline and fall of Teotihuacan allowed smaller regional centers, that had been previously been held back by the dominance of Teotihuacan, to flourish artistically, economically, and politically. There was also an intense competition among these newly important centers, and much of that competition was expressed in new building programs, sculpture, and precious objects.

Temple of Kukulcan (also known as El Castillo), 8th–12th century, Chichén Itzá, Mexico (photo: Pascal, CC BY 2.0)

Post-Classic period, c. 950–1519 C.E.

Finally, in the the Post-Classic period we find developing patterns from the Epiclassic, such as numerous regional centers instead of a great metropolis like Teotihuacan. These regional centers seemed to be linked commercially through ever more complex trade networks that moved everything from volcanic glass to precious jade and shell jewelry. With this economic exchange came trade in religious ideas that seem to echo across much of Mesoamerica.

The Post-Classic is distinguished from the preceding Classic/Epi-Classic by an increase in merchants, and in the importance of merchants in commercial activities on a large scale. Post-Classic art transforms large parts of the Classic artistic tradition. Some Post-Classic artists rejected the most refined elements of the Classic tradition. This is especially true among the Maya, whose Post-Classic traditions dropped the idealizing features of Classic Maya nobles and gods and instead developed a rough carving tradition with seemingly endless lines of similar figures. Sculpture at the large site of Chichen Itzá has hundreds of good examples of the Post-Classic carving style. The major related site of Tula, Hidalgo, also follows this trend.

El Caracol (the Observatory), 8th–12th century, Chichén Itzá, Mexico (photo: Arian Zwegers, CC BY 2.0)

However, the Post-Classic is not, by any means, a complete break with the Classic period. You see people continually reflecting back on the art of the Classic period as they build their Post-Classic social and artistic patterns, at places like Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán and Mitla in Oaxaca.

Page from the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, 1200–1521 A.D., Mixtec. Painted deer skin, 19 x 23.5 cm. The British Museum, London, Am1902,0308.1 (BM Add. MSS 39671). Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

For instance, Oaxacan nobles in the region called the Mixteca created complex hieroglyphic books (such as the Codex Zouche-Nuttall) out of the glyphic tradition found in places like Xochicalco as well as nearby Monte Albán and other Oaxacan sites during the Epiclassic. These people, called the Mixtec, also created a tradition of fine metalworking in gold and silver. Precious metals had not been important to Mesoamerica before this period, although it was well-known to the south of Mesoamerica, especially in the Andes. Mesoamericans had preferred jade as the primary elite material since the time of the Olmecs, but the Mixtec became adept at goldwork, almost certainly learning from peoples on the Pacific Coast of Mexico who learned metalsmithing (creating objects in metal) in turn from peoples farther south.

It is in the Post-Classic period that the Mexica (or Aztec) empire develops and grows, often incorporating elements of peoples they conquered into their art and architecture—including the Mixtec. Merchants were an important feature of the Mexica empire, and there was also a steady stream of raw materials and goods into Tenochtitlan, the Mexica capital city.

Coatlicue, c. 1500, Mexica (Aztec), found on the SE edge of the Plaza mayor/Zocalo in Mexico City, basalt, 257 cm high (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City), photo: Steven Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Spaniards arrive in 1519 and change things drastically enough that we can no longer talk about Mesoamerican civilization in the same terms that are used for the period from 14,000 B.C.E. to 1519 C.E. Indigenous artists continued to erect buildings and decorate them, and they continued to make books. They did so in an artistic landscape so changed that some scholars have spoken of the “extinction” of Indigenous Mexican art. In reality, many Indigenous artists were deeply committed to the new artistic vocabulary of church, cross, and mural, especially when they were building for their own city (pueblo de indios). Indigenous artists have never gone away. They are with us today, continuing to make meaningful and beautiful artistic statements.

Additional resources:

Read an introduction to Mesoamerica

Check out a glossary of pre-Columbian art on Smarthistory

Read about the Mesoamerican calendar

Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc.

Mary Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica from Olmec to Aztec, 6th ed. (2009).

Michael D. Coe, Javier Urcid, and Rex Koontz, Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, 8th ed. (Thames and Hudson, 2019)