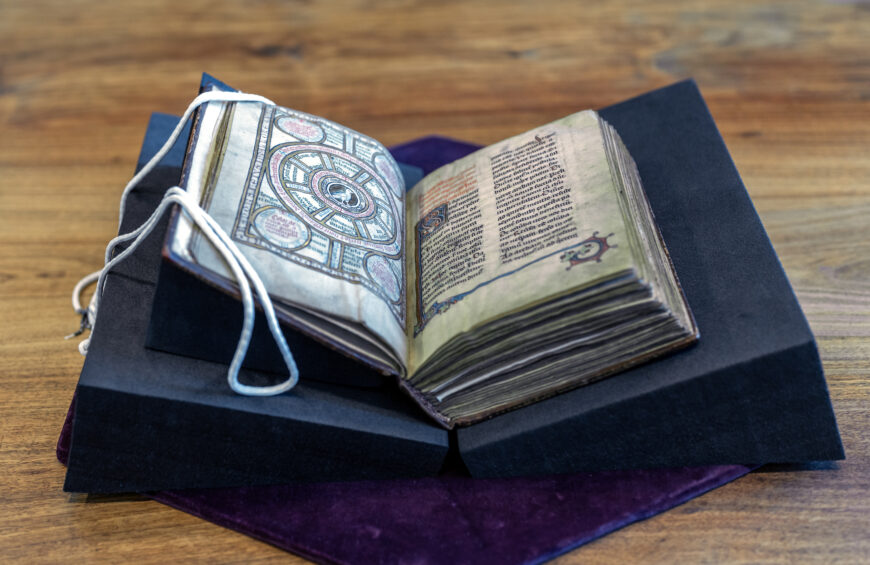

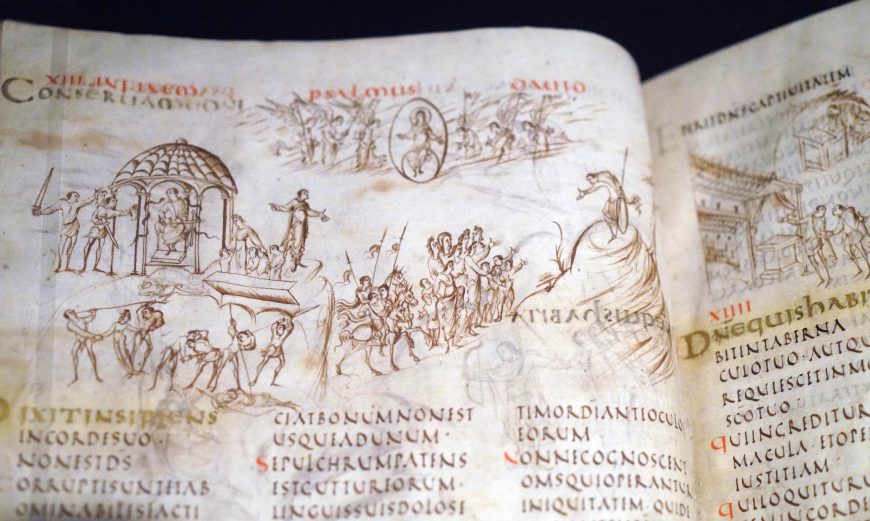

Folio 86 verso, The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260, 28.5 x 20.5 cm (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

The 13th-century Rutland Psalter is a glorious illuminated manuscript featuring the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms (hence the name, psalter). It is also generally considered the earliest surviving British manuscript to have a program of apparently secular pictures created in the margins of a religious text that are referred to as marginalia.

Looking at the Rutland Psalter helps viewers today better understand what concepts like “sacred” and “profane” or “religious” and “secular” may have meant to the people who produced and likely used such a book in the Middle Ages. Spoiler alert: these concepts were likely more fluid, and less mutually exclusive, to viewers of the past than now.

From the grotesque to the conventional

Although it is unclear who the original patron was, scholars guess that its earliest owner was a wealthy layperson since psalters were the books most widely owned by that class of people (at least until the later medieval emergence of the Book of Hours). Typically dated to around 1260, the manuscript contains 7 full- or partial-page miniatures and 102 individual marginal designs. These marginalia comprise an odd array of pictorial interlopers, from grotesque inventions to more conventional monsters such as centaurs, dragons, and harpies (a mythical creature, often depicted with the head and trunk of a woman and the body of a bird). Art historian Nigel Morgan posited that 4 illuminators were responsible for the illustrations in the psalter, but no one today can really say for sure how many artists worked on the manuscript in the Middle Ages. [1]

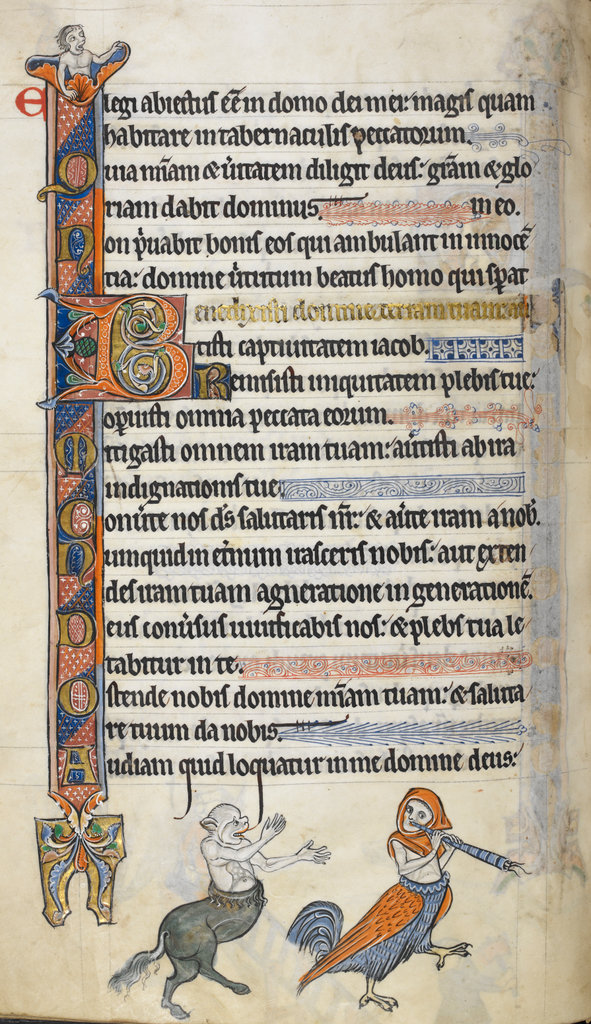

The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260, left: folio 66 verso, Psalm 67, bas-de-page simian riding an ostrich; right: folio 67 recto, Psalm 67, bas-de-page figure (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

As with marginalia generally, the marginal content here is not just surprising in its apparent randomness; it is also, in many instances, suspiciously profane. Consider, for instance, the naked figure on folio 67r (a folio is a page, and “r” refers to the recto, or front page, and “v” the verso, or back of the page). Michael Camille famously argued that he bears a close resemblance to Christ. [2] But he doesn’t behave in a very Christ-like manner. Bending over a mound, the man appears to wave a hand in front of his exposed bum, giving air to what is perhaps a particularly noxious insult intended for the ape astride an ostrich on the opposite, or verso, folio. This ape is fighting back, though; he tilts a long lance toward his offender’s exposed backside.

Folio 67 recto, Psalm 67, bas-de-page figure, The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260 (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

Viewers today might see such imagery as reproachable, vulgar, and even disturbing. But there may be a method to the artist’s madness here. Above the man, the viewer reads the word tympanistriarum, a reference to the drummers of Psalm 67. The artist seems to have taken the word out of context in the Psalm to create a visual pun: the hand gesture of the Christ-figure may not be an attempt to diffuse an offensive odor so much as a drum-beat on his derrière. That is, he appears to act out the text above. Scholars today increasingly believe that such visual word play is not meant to be seen as gratuitous and offensive; instead, it interrupts the viewer and, in so doing, slows down his (or her) reading of the text—inviting them to pause upon the page and meditate more fully on the content of the Psalm.

Punning and verbal-pictorial translation

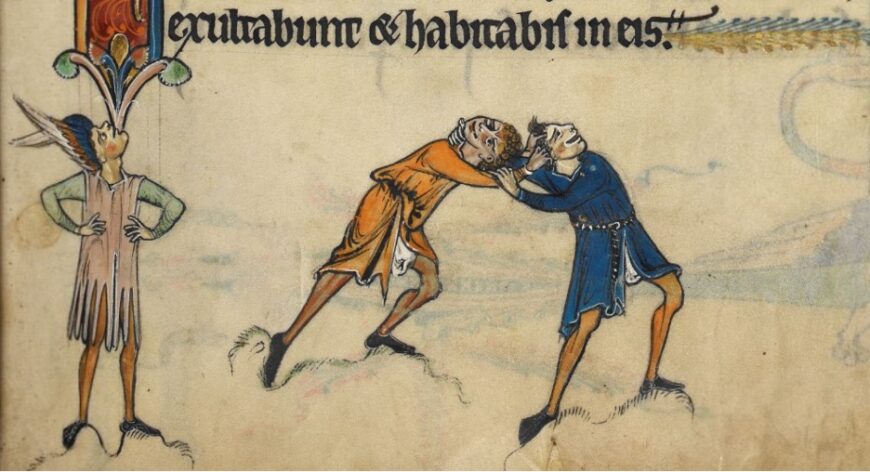

Punning and verbal-pictorial translation may be the very hallmark of the manuscript’s marginalia. Indeed, the Rutland Psalter’s text contains a number of examples in which the marginal images look like actions or activities described, or apparently described, by snippets of the text they accompany. One of the most striking examples of this center-margin interplay occurs at the opening spanning folios 10v and 11r. Beginning at the bottom quarter of the verso page, fronted by a historiated initial “V” for Verba, the first line of the Psalm reads: Verba mea auribus percipe Domine intellege clamorem meum (“Give ear, O Lord, to my words, understand my cry”).

Two men in tights and short tunics wrestle. Folio 11 recto, Psalm 5, bas-de-page wrestlers, The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260 (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

This phrase is taken literally by the illuminator in the bas-de-page, or lower margin, of folio 11r. Two men in tights and short tunics wrestle; the figure to the viewer’s left grabs the other by his ear. In this case, the ear is given only by force, presumably to remind the viewer of the sense of the text and its appeal to the ear of God. It might also be noted that the figure depicted beside the wrestling pair, just inside of the fold at the foot of the vertical border, stands with his head back and mouth open as if issuing forth the cry (clamorem) on the page above, here transformed into a decorative edging.

Folio 14 recto, Psalm 9, bas-de-page scene, The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260 (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

Another example occurs at folio 14r. Psalm 9 begins on the facing page (folio 13v), about a quarter of the way down the page at a historiated initial “C” for Confitebor. It contains the line: in laqueo isto quem absconderunt comprehensus est pes eorum (“Their foot hath been taken in the very snare which they hid.”) The bas-de-page (bottom of the page) scene depicts a man in a blue garment before one of the many long-necked dragons that populate the manuscript’s margins. The dragon grasps the man’s foot in its mouth, as he clings to the vertical border. The artist has taken the text literally, such that the “foot” (pes) of the man has indeed been taken by a “snare” (laqueo) in the form of the dragon.

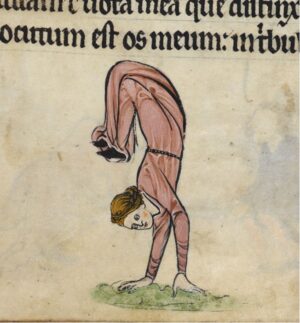

Folio 65 recto, Psalm 65, bas-de-page acrobatic figure, The Rutland Psalter, c. 1260 (The British Library, London, MS 62925)

On folio 65r, the bas-de-page contains an image of a figure standing on his or her hands in a sort of somersault. This is perhaps in reference to the phrase from Psalm 65:12, written just a few lines overhead: Inposuisti homines super capita (“Thou hast set men over our heads”). In this case, the illuminator has depicted a man quite literally super capita (“over head”).

These examples suggest an almost comically direct translation process, in which a perhaps “functionally” literate artist read (or attempted to read) the text on the folio he was to illuminate and used words and phrases as a springboard for his imagination. Such a process was likely spontaneous, or at least subject to less rigorous planning than the full- or nearly full-page miniatures that also populate the manuscript.

A framing device, sometimes ambiguous

We should note, though, that many of the manuscript’s margins are ambiguous, and it is not always possible to read marginal figures on a given folio as cohesive or related to the text they accompany. As a result, scholars generally allow that some margins had a more playful, even decorative function, even if some are inspired by aspects of the text they accompany. This simply suggests the lack of uniformity that dominated artistic approaches to the margin. Ultimately, the marginal figures of the Rutland Psalter are perhaps best described as a second frame—or as, in any case, a framing device. They frame, even mirror, the viewer’s engagement with the text at the center.

Designed for literate lay-consumption, the marginalia of the Rutland Psalter challenged the reader’s comprehension, perhaps in an effort to get him or her to come back continuously and often. After all, lest we modern viewers forget, manuscripts were meant to be looked at repeatedly, used frequently, analyzed closely, and meditated upon again and again. In fact, the Rutland Psalter so enthralled William Morris, the father of the Arts and Crafts movement, that he asked for it on his deathbed.