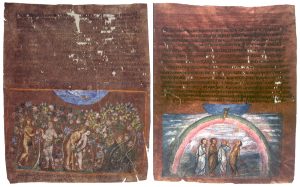

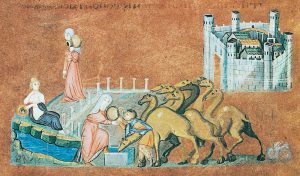

The fall of man and God’s covenant with Noah, from the Vienna Genesis, folio 3 recto, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

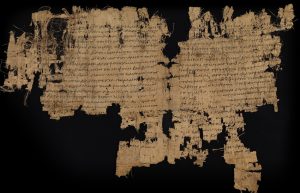

Wealthy Christian families living in the Byzantine world may have aspired to own a new kind of luxury object: the illustrated codex. Before the invention of printing in the 15th century, all texts were written or carved by hand. In the ancient world, manuscripts (texts written by hand) were found on a variety of portable surfaces. In the ancient Near East scribes wrote on clay tablets. In ancient Egypt and the ancient Greek and Roman world, information could be stored temporarily on wooden tablets coated with wax. A more lasting solution was to use scrolls made of papyrus (below): fibrous reeds that were dried in overlapping layers and then polished with a stone to create a smooth surface. Authors of papyrus scrolls usually divided their work into sections based on how much text could be held on a single scroll, leading to the concept of “chapters.”

Scripture Interpreted by Philo of Alexandria, papyrus manuscript fragment, 3rd century CE, Egypt, 20.3 x 30.5 cm (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

New materials, new possibilities

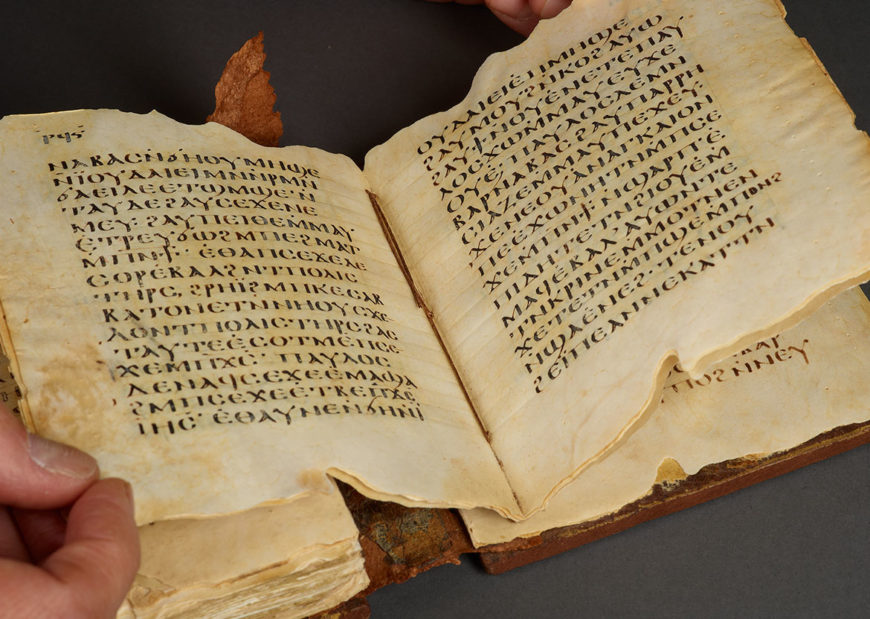

All of these materials preserved texts for the few literate members of the population, but the limitations of the materials themselves made it difficult to add illustrations to the text. Papyrus scrolls were rolled for storage and then unrolled when read, causing paint to flake off. Text was scratched into the surface of a wax or clay tablet with a stylus, so only basic shapes could be created. Some time in the first or second century, however, the parchment codex (below), a more durable and flexible means of preserving and transporting text, began to replace wax tablets and papyrus scrolls. The new popularity of the codex coincided with the spread of Christianity, which required the use of texts for both the training of initiates and ritual practices.

Acts of the Apostles, Glazier Codex, 5th century, parchment (The Morgan Library and Museum)

The codex form allowed readers to find a discrete section of text quickly and to carry large amounts of text with them, which was useful for priests who traveled from place to place to serve communities of Christians. It was also essential for a religion that relied on text to establish the details of belief and set standards of conduct for its members. The vast majority of these codices were not decorated in any way, but some contained illustrations done with tempera paint that pictured events described in the text, interpreted these events, or even added visual content not found in the text.

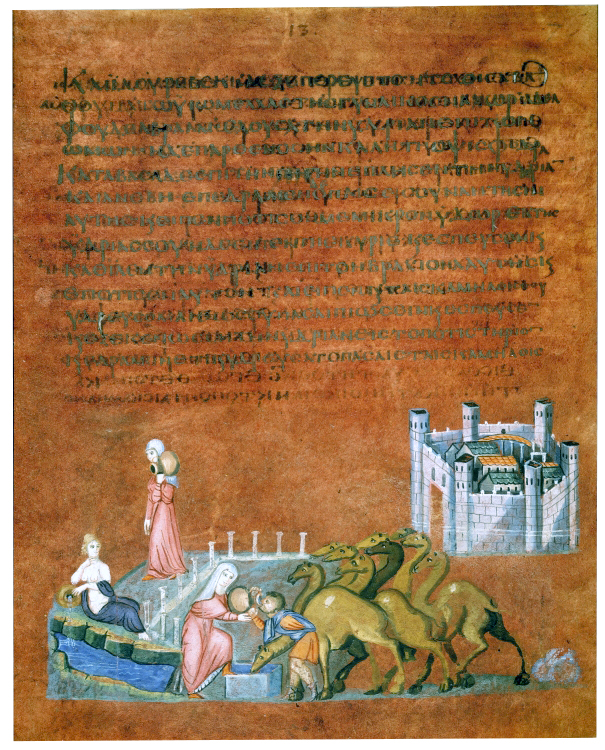

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

A luxurious codex

The Early Byzantine Vienna Genesis gives us a taste of what manuscripts made for a wealthy patron, likely a member of the imperial family, might have looked like. Genesis—the first book of the Christian Old Testament—described the origin of the world and the story of the earliest humans, including their first encounters with God.

The Vienna Genesis manuscript, now only partially preserved, was a very luxurious but idiosyncratic copy of a Greek translation of the original Hebrew. The heavily abbreviated text is written on purple-dyed parchment with silver ink that has now eaten through the parchment surface in many places. These materials would have been appropriate to an imperial patron, although we have no way of knowing who that was. The Vienna Genesis may have been a luxury item intended for display, or it may have provided a synopsis of exciting stories from scripture to be read for edification or diversion by a wealthy Christian.

Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Telling a story

The top half of each page of the Vienna Genesis is filled with text, while the bottom half contains a fully colored painting depicting some part of the Genesis story. In the scene above, Eliezer, a servant of the prophet Abraham, has arrived at a city in Mesopotamia in search of a wife for Isaac, Abraham’s son. The artist has used continuous narration, an artistic device popular with medieval artists but invented in the ancient world, wherein successive scenes are portrayed together in a single illustration, to suggest that the events illustrated happened in quick succession. In the upper right hand of the image a miniature walled city indicates that Eliezer has arrived at his destination. Rebecca, a kinswoman of Abraham, is shown twice. First, she walks down a path lined on one side with tiny spikes that symbolize a colonnaded street. Rebecca approaches a reclining, semi-nude woman who allows an overturned pot to drain into the river below. This is a personification of the river that feeds the well to the right, where Eliezer waits. Rebecca is shown a second time offering Eliezer and his camels a drink, a sign from God that she is to be Isaac’s wife.

Detail of Rebecca and Eliezer at the Well, folio 7 recto from the Vienna Genesis, early 6th century, tempera, gold and silver on purple vellum, 31.75 x 23.5 cm (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna)

Ancient themes, new techniques

The personification of the river reveals the image’s classical heritage, as does the use of modeling and white overpainting which lend naturalism to the garment folds and the swelling flanks of the camels.

The Vienna Genesis combines pictorial techniques familiar from the ancient world with content appropriate to a Christian audience, which is typical of Byzantine art. Though many of the details of this manuscript’s production and ownership have been lost, it remains an example of how artists combined ancient modes of expression with the most current materials and forms to create luxurious objects for wealthy patrons.