Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., Green Dining Room (now The Morris Room), 1866–67 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London; photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum)

Philip Webb, Design for the wall-decoration and cornice in the Green Dining Room, c. 1866, pencil and watercolor (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The Green Dining Room is one of the best surviving examples of the aesthetic of William Morris, designer, poet, socialist, and preservationist. The room was commissioned in 1865 as a refreshment room in what was then called the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). Morris and his colleagues (primarily painter Edward Burne-Jones and architect Philip Webb), created a tranquil, nature-inspired spot for museum patrons to enjoy a cup of tea. In keeping with the ideals of the Aesthetic Movement (where artists sought to create works that were admired simply for their beauty rather than any narrative or moral function), the harmonious muted color-scheme, emphasis on craftsmanship, and the medieval vibe of the stained glass and woodworking, the room shows Morris’s style of interior design at its finest.

Fashion for the medieval

William Morris was born in Essex in 1834, the son of wealthy middle-class parents. Raised reading the romanticized historical novels of Sir Walter Scott, Morris developed an affinity for the prevailing fashion for medievalism, which many saw as an antidote to the problems of modern industrial Britain. Conservative thinkers such as Thomas Carlyle in Past and Present (1843) sought to point out the deficiencies of the modern world by comparing them to practices of the medieval past.

Politicians also decried industrial practices in favor of bygone traditions, such as Conservative MP Lord John Manners who in his A Plea for National Holydays (1843) proposed allowing factory workers to dance around a maypole as a solution to working class unrest. Steeped in medieval nostalgia, the story that the 16-year-old Morris refused to visit the immensely popular Great Exhibition of 1851, which celebrated everything industrial, makes perfect sense.

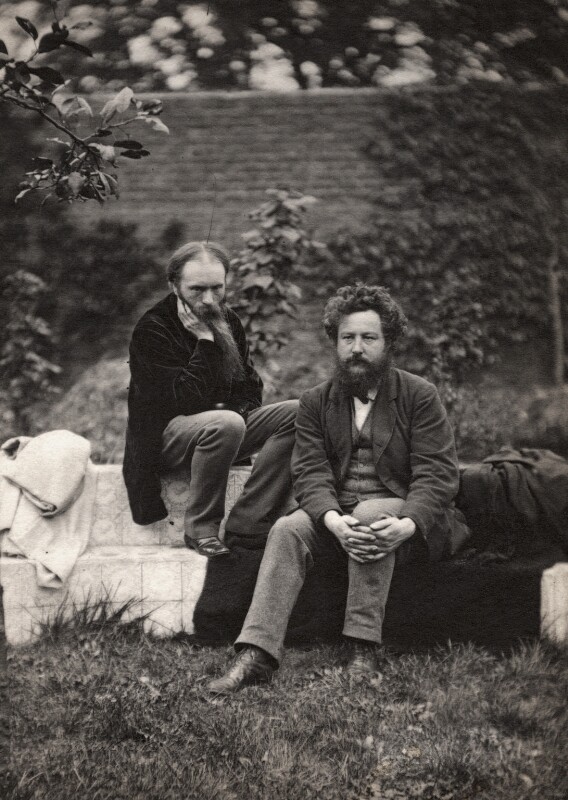

Frederick Hollyer, Sir Edward Burne-Jones; William Morris, 1874, platinum print (National Portrait Gallery, London)

While a student at Oxford, Morris met Edward Burne-Jones, who would become a celebrated Victorian painter, and the two became friends, joined by a love of culture and all things medieval. This connection was further cemented when the pair met the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti and worked with him on creating a series of paintings derived from the Arthurian legends to decorate the Oxford Union. At the time Morris was apprenticed to an architect and abandoned this career to pursue art. Unfortunately, he soon realized that he lacked the same skill as his friends, but quickly discovered a talent for design, creating items such as furniture and manuscripts in a medieval style.

William Morris and Philip Webb, The Red House, 1860, Bexleyheath, London (photo: public domain)

Morris’s first large scale decorative project was his own house, known as The Red House due to the red brick exterior. Designed by Philip Webb and completed in 1860, Morris commissioned the house as a home for his wife Jane Burden, whom he married in 1859, and their two daughters. The L-shaped plan of the house echoes medieval house plans and Morris’s artistic friends helped him decorate the interior with scenes from Arthurian legends, and the stories of Chaucer, interspersed with a few classical illustrations from the Trojan War. For financial and logistical reasons, Morris sold the house in 1865.

In 1861, Morris founded the firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., a joint venture founded by Morris, P.P. Marshall, and Charles Faulkner, along with Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Philip Webb. Their medieval inspired and handcrafted items for the home were an almost immediate success, and the work of “the Firm” can still be found in churches that were renovated by the Victorians and some more avant-garde homes of the period.

“The Firm” became known for its beautiful stained-glass designs, embroidered hangings, furniture, textiles, and carpets, all of which were produced using traditional methods. Morris insisted on forgoing industrial mass production of his objects, maintaining that the work of one’s hands was more beautiful than something made by machine. His famous saying “have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful” became a challenge to the cluttered, overly decorated, and to Morris’s mind, less beautiful interiors commonly found in Victorian homes.

Stained glass panels, part of a series entitled The Garland Weavers, designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made by Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. England for the Green Dining Room, 1866–67 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The Green Dining Room is an excellent example of Morris’s design ideas. The muted green, blue, and gold color scheme creates a calming backdrop to the beautiful stained-glass windows depicting women in floating white dresses, designed by Burne-Jones.

Left figure: Sagittarius; right figure: Capricorn. After Edward Burne-Jones, by Charles Fairfax Murray, Signs of the Zodiac for the Green Dining Room, c. 1866, oils, tempera on canvas/panel and mixed media (Victoria and Albert Museum, London). Note: Burne-Jones drew the original designs and Morris & Co. employed several different painters to paint the panels. Morris was unhappy and had them all, except one, repainted by Charles Fairfax Murray

The dado rail which forms a barrier above the dark greenish stained woodwork in the lower portion of the room also contains Burne-Jones designs of the signs of the zodiac interspersed with plant motifs. Above the rail the walls are decorated with a low plaster relief design of olive branches in a paler, yet tonally complementary shade of green.

Next to the ceiling is a frieze depicting hounds pursuing hares. The gold color that surrounds each animal leads the eye to the golden designs on the tray ceiling formed from stylized stencils of plants, which are reminiscent of the many wallpaper and textile designs Morris would go on to produce.

Together with the two other refreshment rooms in the museum, The Gamble Room and the Poynter Room, The Green Room created a relaxing atmosphere for museum patrons to take a break. The museum’s director, Henry Cole, inaugurated the concept of the museum café, an idea which would not become standard until the 20th century. Cole was also the first to install gas lighting, which allowed the museum to open in the evening. Many of his innovations are now standard in museums around the world.

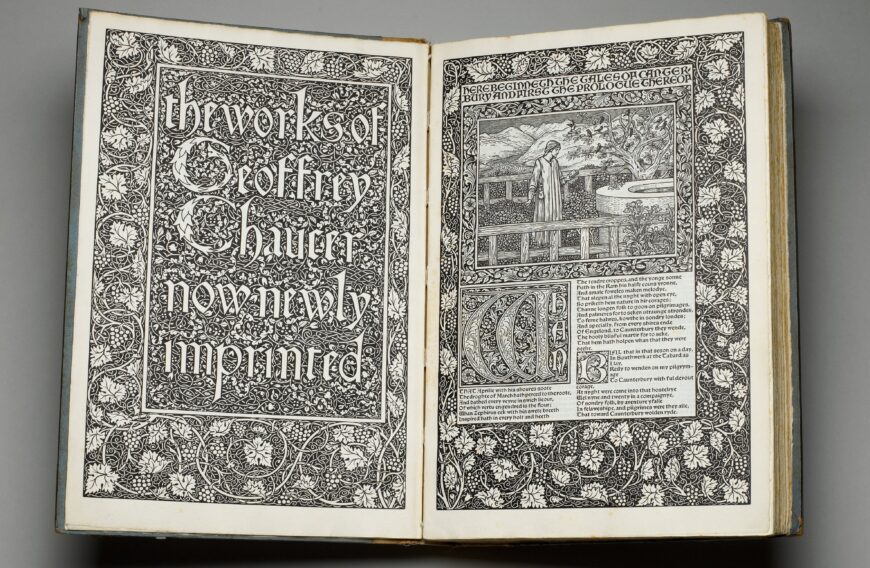

The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, now Newly Imprinted, artist: William Morris; author: Geoffrey Chaucer; illustrator: Edward Burne-Jones; engraver: William Harcourt Hooper; editor: Frederick S. Ellis; printer: William Morris (Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1896) (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Morris would go on to become one of the world’s foremost designers. In 1875 Morris took control of “the Firm,” which became known as Morris & Co. In 1871 Morris purchased a country house in the village of Kelmscott. The surrounding countryside provided inspiration for many of his designs, not only in his textiles but also for the manuscripts published by the Kelmscott Press, which Morris founded in 1891. Based on medieval illuminated manuscripts, the books published by Kelmscott Press included the celebrated Kelmscott Chaucer, as well as some of Morris’s own writings such as News from Nowhere (1890). An accomplished poet in his own right, Morris used his writings to explain his own utopian views of society.

Throughout his life, Morris leaned more and more towards the views of socialism and became disillusioned with contemporary society. Unfortunately, his idea that everyone deserved beauty was at odds with his insistence that his products be handmade rather than using industrial processes. The workmanship that went into Morris’s products made them very expensive and financially out of reach for all but the well off. It was an issue he was never able to reconcile.

The designs of William Morris left an indelible mark on Victorian society, which is still seen today. One can still purchase the work of Morris & Co., and his designs are reproduced for many mass markets, particularly textiles, wallpaper, and rugs. His “less is more” attitude resonates with many today, and the simple, natural beauty of his designs still looks fresh over 100 years later.